Lesson 5- Transect Layout & Wetland Classification

Learning Objectives

This lesson covers the basic data to collect within the wetland portion of the transects in order to classify the wetland according to ecological type. The Protocol and technical guidance document are important companion resources. You should never go to the field without having one of these with you (uploaded to your device or a hard copy). Once in the field, before starting any measurements, you will first confirm the wetland is a wetland, the wetland polygon boundary is accurate/appropriate, and the wetland is within two riparian management areas if it is to be included as an official FREP site.

In this lesson you will learn:

- How to layout your transect

- What basic data to collect to determine wetland type

Entire Wetland Sampled or Partial Wetland Sampled

Most of the time, you will be able to sample the entire wetland, but on occasion you’ll need to constrain your sampled wetland to a smaller portion. Partial wetland sampling may be warranted if the wetland is too large; or there is a physical barrier that prevents you from making observations at a specific section (e.g., deep stream crossing).

Transects

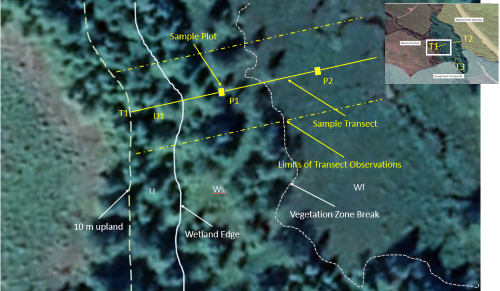

Establishing POC: Transects are used to sample each of the dominant upland strata identified during the office pre-work, with at least one transect placed in each stratum. Transects are numbered consecutively starting at one, and are conventionally labelled: T1, T2, T3. The location of the transects are set using a random number selection that represents meters along the perimeter for each stratum. Once located in the field, you will record the geo-coordinates at the wetland edge where you place your transect. It’s also helpful to place flagging tape at the boundary and record FREP W/L with the Transect #.

Entering the wetland: Once you’ve flagged the edge of your wetland and set a bearing that is perpendicular to the wetland perimeter, you will walk into the wetland with a rotary tape, keeping 0m at the edge with the tape rolling out with increasing meters. It’s helpful to have one field partner hold the rotary tape at the wetland edge, and ensure the other partner stays on their bearing.

While walking, you will use flagging tape to mark zones of wetland vegetation at distinct breaks that depict different wetland plant associations. The center of these zones will be the site of the sample plots. The transect will end at one of either: 50m, middle of the wetland, open water, or other feature that makes reaching the desired 50m length impractical, so not all transects may be of equal length. Therefore, each transect length is also recorded as the fraction of the total transect length once the total for all transects is known. Later measurements will use this fraction to accurately weight data along each transect which will be added together to give a weighted average for the entire wetland. To complete the transect, a 10 m length is added into the upland/riparian zone where a slightly different set of indicators will be measured.

Figure: Placement of the field transect and location of sample plots relative to wetland zones.

Field Measures and Observations

This section describes a few of the measurements and observations you will record while working through the transects and plots. The full list of attributes to be recorded on the field forms and step by step instructions on completing the tables can be found in the Protocol and the FREP wetlands technical guidance document.

Wetland Soil Information: Wetlands are defined by soils that have been modified by the presence of water due to the anaerobic or oxygen-deficient nature of water submersion. Wetland soils are categorized into mineral (inorganic) or organic soils. Both types of soils present indicators that they have been modified by water:

- Mineral soils exhibit gleying (uniform blue-grey mineral soil) or mottling (reddish-brown splotches in soil).

- Organic soils exhibit peat in various stages of degradation.

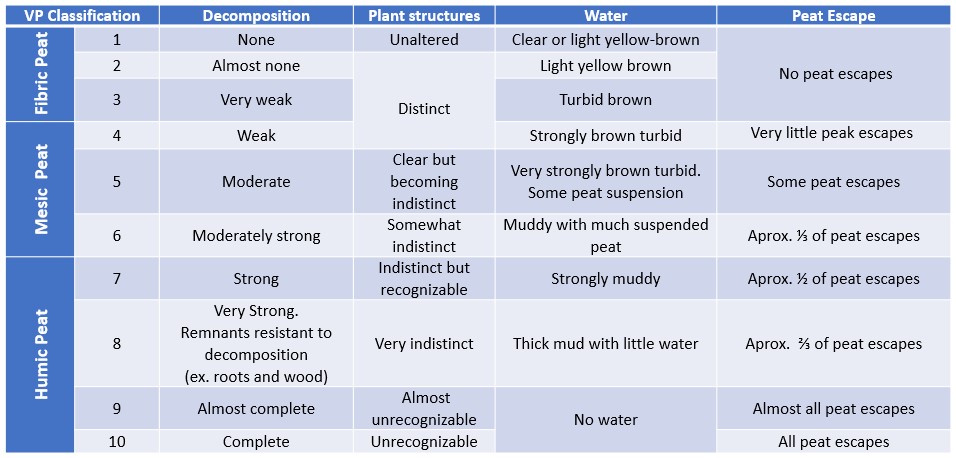

Organic Soil Characterization: Organic soils can further be categorized by its decomposition, or humification, using the von Post method. To use this test, a palmful of wet soil is squeezed very hard, until as much as possible has escaped through the fingers. The amount of peat that escaped and the colour of the water is then assessed with a chart to determine if the soil is Fibric, Mesic, or Humic. For a more detailed explanation of this method, you can view this video.

Depth to Water, pH and Temperature: Water can be below, at, or above the surface depending on the type of wetland. Water below the surface is recorded as a positive number and water above the surface is recorded as a negative number. pH and temperature can be measured either directly from the soil using a special soil pH meter or from the water with a common pH meter. For samples from water, take the measurement at the surface or where the water-table is inside the excavation hole of the soil core. If you are in a sphagnum bog, sample water by squeezing peat into a small container if it has recently rained because recently-pooled water may not reflect the pH of the site very well.

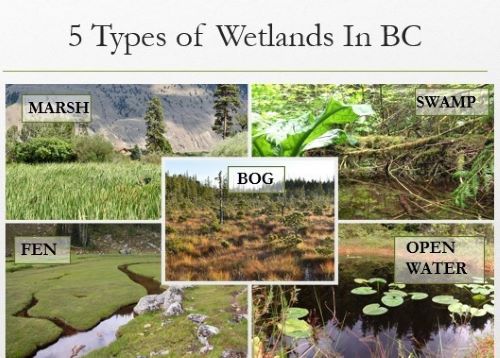

Wetland Ecological Classification

Consistent with the Canadian Classification System and within B.C.’s Land Management Handbook 52: Wetlands of British Columbia , there are 5 types of freshwater wetlands found within BC: bogs (Wb), fens (Wf), marshes (Wm), swamps (Ws), and shallow open water (Ww). The wetland classification and its plant association can be determined by the soil type and pH in combination with the vegetation information that you will be collecting.

Overview of the Five Classes of Wetlands:

Bogs (Wb)

- Peatlands with mesic or fibric organic soils. Water table is generally below the surface. Typically, no connection to groundwater. Influenced by rainwater as primary input of water. No seasonal flooding or water flow. Vegetation primarily dominated by a layer of sphagnum and soil of decomposing sphagnum. Highly acidic, nutrient poor. Common plants: sundews, labrador tea, bog laurel, stunted shorepine, black spruce. Visit BC Wildlife Federation’s (BCWF) virtual Bog Tour

Fens (Wf)

- Peatlands with mesic or fibric organic soils. Common in mountainous areas in the south; more widespread further north in the Province of BC. Wetter than bogs with more nutrients due to greater connectivity to groundwater. Slightly acidic to neutral. Organic peat built up primarily from graminoid species and brown mosses. Common plants: often dominated by sedges or other graminoid species. Visit BCWF’s virtual Fen Tour

Marshes (Wm)

- Mineral wetlands or humic organic soils. pH typically neutral to alkaline. Periodically flooded by slow-moving or standing water. Rich in nutrients. Vary from fresh to saline water. Common in dry climates but found throughout province. Although vegetation can sometimes be similar, hydrology is more dynamic than fens. Doesn’t allow for build up or fibric or mesic peat due to fluctuations in oxygen levels in soils. Often next to lakes, streams. Common plants: non-woody emergent vegetation, cattails, bullrushes, grasses and sedges. Visit BCWF’s virtual Marsh Tour

Swamps (Ws)

- Mineral wetlands or humic organic soils (sometimes with coarse woody fragments). Fluctuating water tables – similar to marshes. Standing or slow-moving water. Pronounced internal water movement. Rich in nutrients. Decomposed wood. Plants: trees & shrubs often occupying raised hummocks. Common plants: willow, red-cedar, skunk cabbage. Visit BCWF’s virtual Swamp Tour

Shallow Open Water (Ww)

- Open water covers at least 75% of wetland in summer. Mid-summer depth <2m. Common on lake margins, can occur adjacent to many other wetland types. Plants: floating and submerged aquatic vegetation (e.g., pond lilies, pond weeds, bladderwort). Visit BCWF’s virtual Shallow Open Water Tour

Plant Association

Wetland types can further be classified by plant association, which are similar in concept to a Bio-geoclimatic site series. Marshes, for instance can be further classified in terms of their dominant plant cover (e.g., Cattail marsh is a Wm04). This step is optional for the FREP assessment, although classifying down to plant association can improve your understanding regarding the underlying ecological drivers of your wetland ecosystem and identify possible issues. It is a good idea to download or print Wetlands of British Columbia: A Guide to identification (Mackenzie & Moran, 2004) to help determine wetland class.

LESSON 5: Self Check Questions

True or False:

- All transects are 60 m in length (50 m into the wetland and 10 m upland)

- By definition, wetlands need to have water visibly present at the surface

Answers

- False – there are multiple reasons that your transect may be shorter than 60 m (e.g., deep channel, you’ve reached the middle of the wetland, etc.)

- False – Many wetlands have water that is slightly below the surface, and never express surface water. Some wetlands that are seasonal or ephemeral will only hold water at the surface for part of the year.