Atrial Fibrillation - Diagnosis and Management

Effective Date: July 26, 2023

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Epidemiology

- Screening

- Diagnosis and Assessment

- Management of AF/AFL

- Stroke Prevention

- Management of Rate and Rhythm in An Acute Care Setting

- Management of Rate and Rhythm in the Outpatient Setting

- Management of Comorbid Conditions

- Indications for Potential Specialist Referral

- Resources

- Appendices

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation (AF) including the primary prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in adults aged ≥ 19 years. It also covers the management of AF in the acute care and outpatient office settings. Management of atrial flutter (AFL) is also included.

Key Recommendations

- Opportunistic screening for AF (pulse check for 20 seconds) in people ≥ 65 years is recommended.

- Treat all patients with valvular AF (mechanical valve or moderate to severe mitral stenosis) with warfarin (direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs] should not be used).

- Use the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) Algorithm (“CHADS-65”) in all patients with non-valvular AF to determine the need for stroke prevention therapy.

- DOACs are recommended in patients age ≥ 65 years or with CHADS2 score ≥ 1 who have non-valvular AF.

- Rhythm control is preferred as the initial treatment strategy in patients with recently diagnosed AF (within a year) because it is associated with reduced cardiovascular death and reduced rates of stroke.

- Long-term oral antiarrhythmic therapy should not be continued in patients when AF becomes permanent.

- Patients with AFL should be stratified and managed in the same manner as those with AF, except that catheter ablation is preferred over pharmacotherapy for rate/rhythm control.

- Manage contributory comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure.

- Use the CCS Symptoms of Atrial Fibrillation (CCS-SAF) score to help triage patients with Class 3 or 4 severity for specialist care.

- Use of i.v. β-blockers, diltiazem, verapamil, digoxin, and amiodarone are contraindicated for acute management of pre-excitation AF (e.g., Wolff-Parkinson-White) because of the potential to precipitate a life-threatening arrhythmia.

Definition1,2

By convention, the diagnosis of AF requires electrocardiogram (ECG) documentation of an irregular rhythm with no discernible, distinct P waves, lasting at least 30 seconds.

AF is classified according to the persistence of episodes (Refer to Appendix A: Types of Atrial Fibrillation) and valve structure.

Valvular AF: AF in the presence of moderate/severe mitral stenosis or mechanical valve.

Non-valvular AF (NVAF): all other patients without the presence of moderate/severe mitral stenosis or mechanical valve.

The prevalence of AF is estimated to be 3% in the general population and increases significantly with age (< 1.0% up to 50 years of age, 4% at 65 years, and 12% of those 80 and older). AF can occur in up to 50% of young patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. For a list of risk factors for AF see Appendix B: Risk Factors for the Development of AF.

AF is independently associated with a 1.5- to 4-fold increased risk of mortality (predominantly due to increased risk of thromboembolic events and ventricular dysfunction). Non-anticoagulated patients with AF have a 3- to 5-fold increased risk of stroke. To date, the only therapeutic intervention that has been consistently shown to improve survival in the AF population is the use of an oral anticoagulant (OAC).1

AFL also carries a significant risk of stroke/system embolism (annual risk ~3%) and often co-exists with AF.

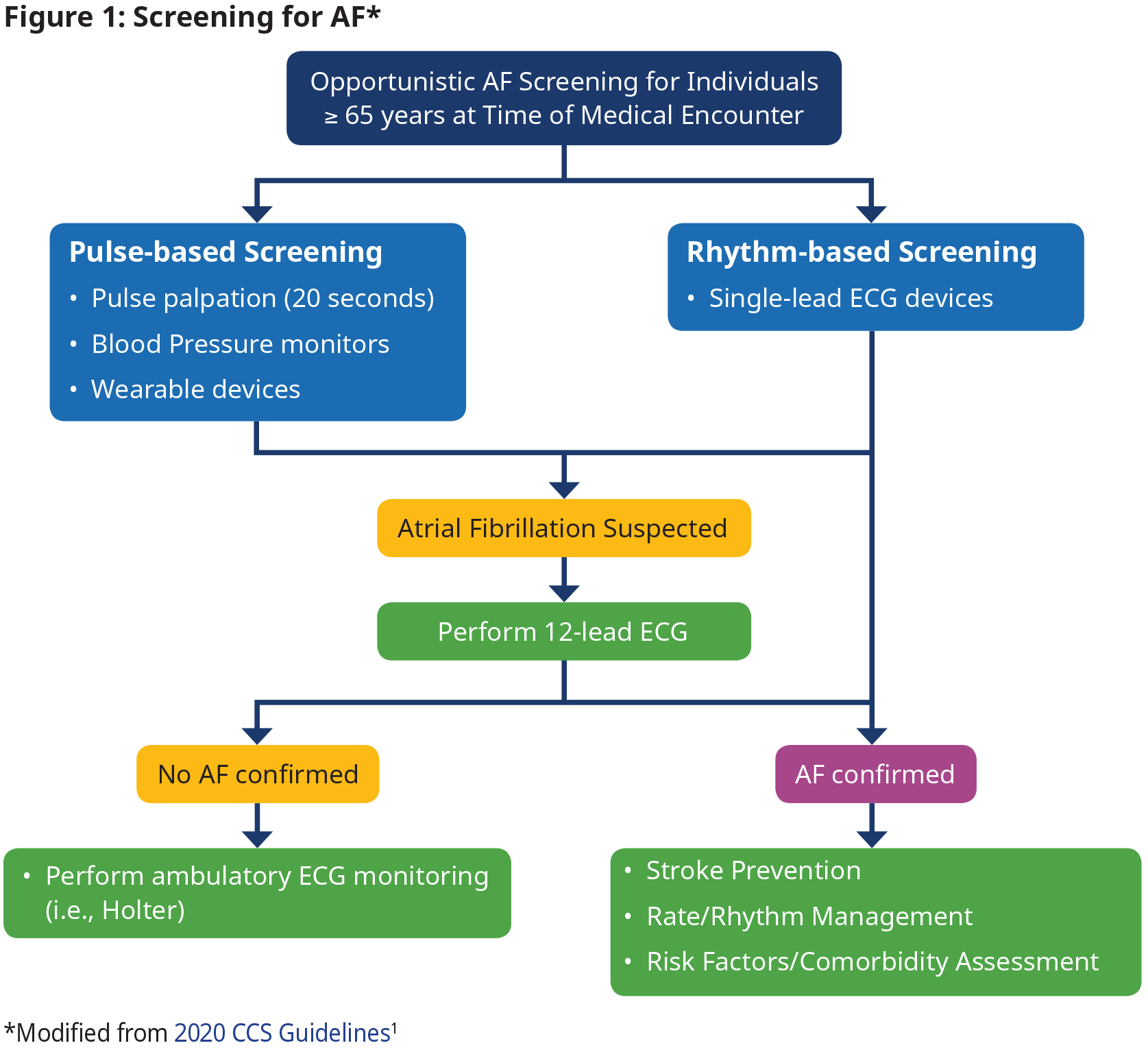

Screening

Opportunistic screening for AF in people ≥ 65 years is recommended.1

- Definition of an AF episode is 30 seconds.

- When a pulse check or a wearable device suggests the presence of AF, confirmation with a 12-lead ECG or ambulatory Holter monitor is required.

- A 12-lead ECG is not needed for confirmation of diagnosis if AF is detected on a single-lead rhythm strip.

- Perform additional testing (e.g., ambulatory ECG monitoring) as needed when AF is not confirmed with 12-lead ECG, but suspicion still exists.

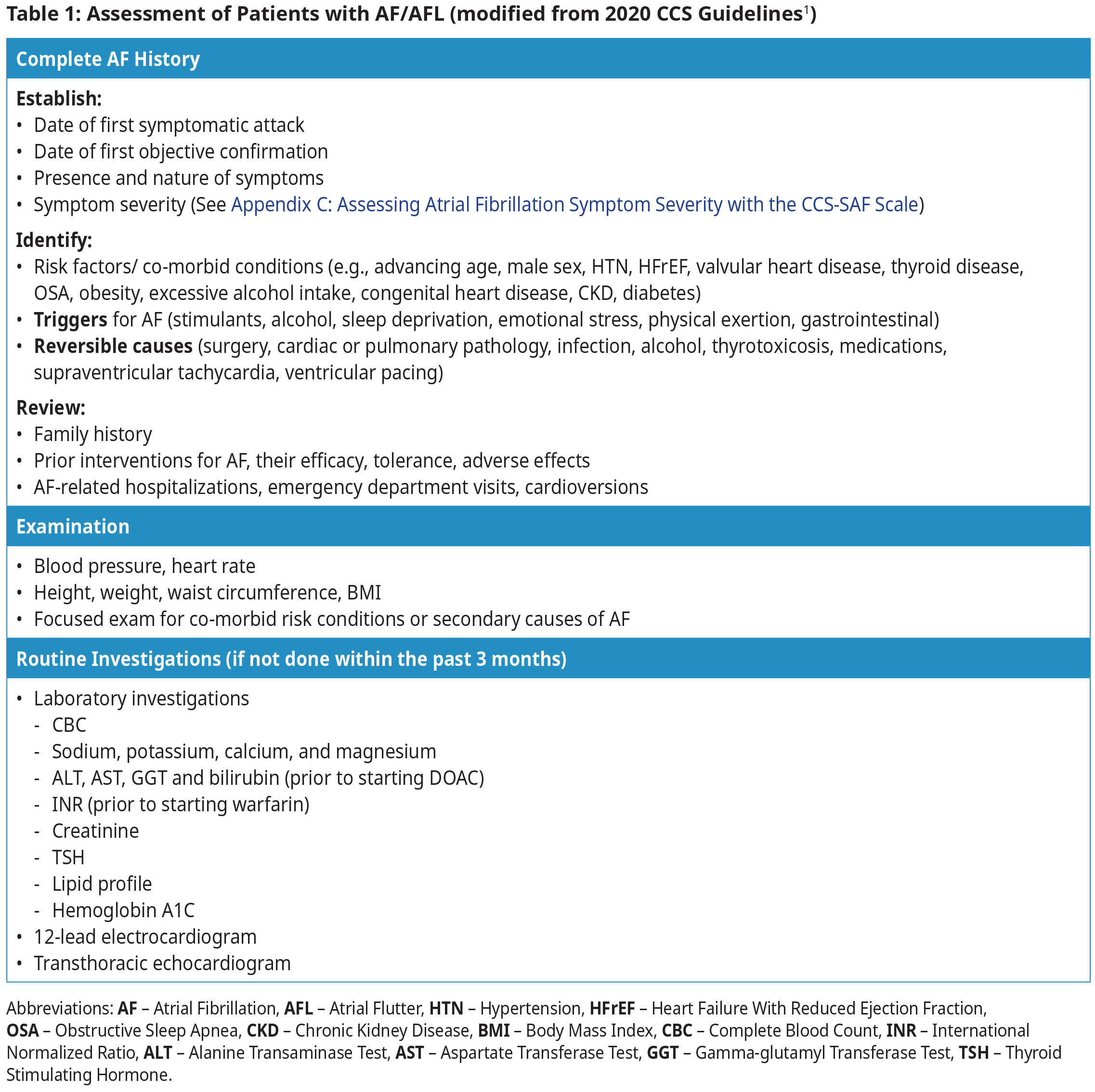

Diagnosis and Assessment1

Patients with AF/AFL may be asymptomatic or may present with symptoms such as palpitations, dyspnea, dizziness, presyncope, syncope, chest pain, weakness, or fatigue. Assessment requires a targeted history, physical examination, ECG, and laboratory investigations.

The goals of AF/AFL management are to:

- prevent stroke and systemic thromboembolism

- reduce cardiovascular risks

- improve symptoms, functional capacity, and quality of life

- prevent complications (e.g., left ventricular dysfunction).

There are three pillars in the management of AF/AFL:

- Stroke/systemic embolism prevention

- Arrhythmia management (i.e., rate and rhythm control). Approach to rate and rhythm control differs somewhat depending on the duration of AF and whether the patient is presenting in an outpatient or acute care/emergency department setting.1

- Management of modifiable risk factors and comorbidities

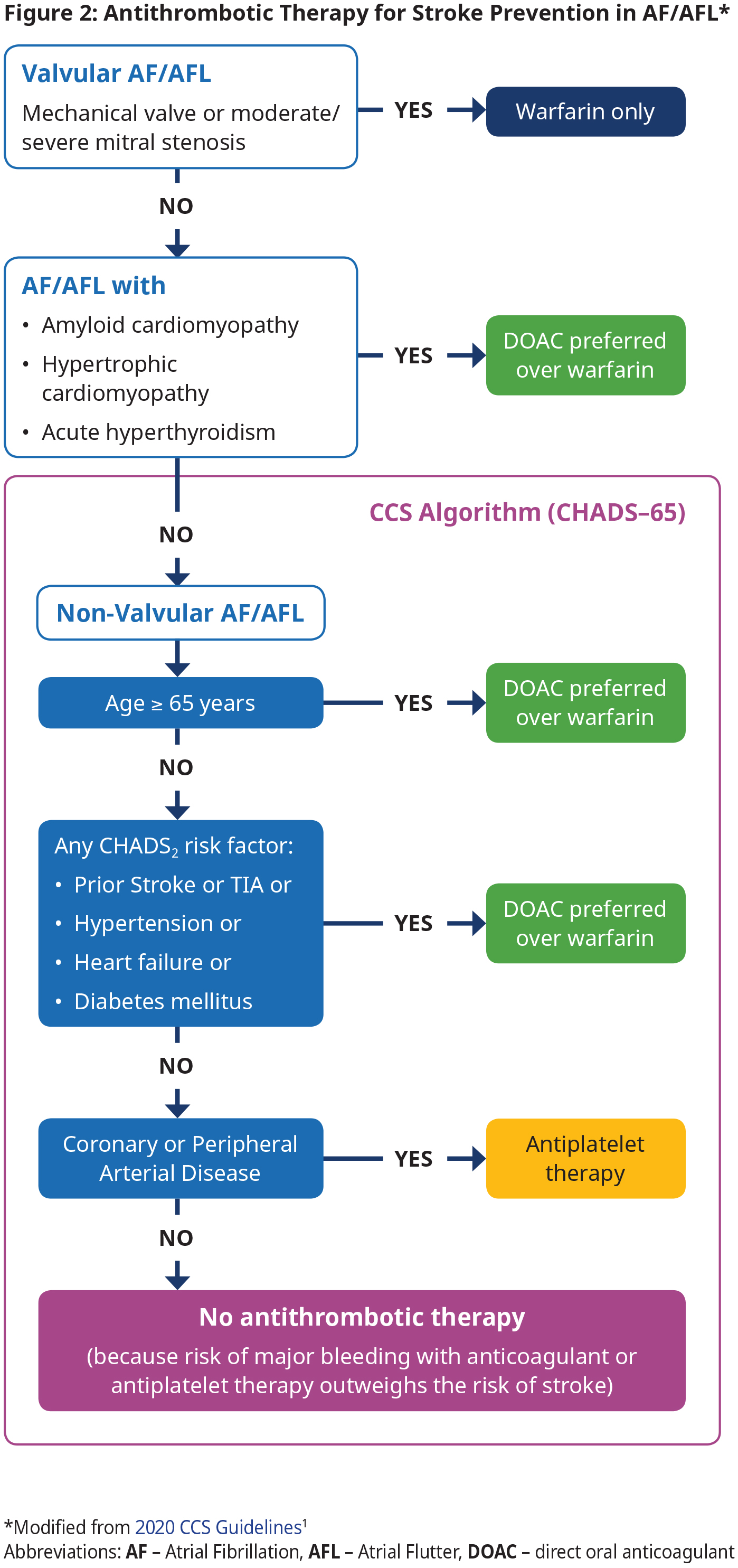

Stroke Prevention

Antithrombotic therapy using an OAC is the cornerstone of stroke and systemic embolism prevention in AF by reducing the risk of cardioembolic events.1 Most patients will require and benefit from OAC therapy. OAC is indicated in those with valvular AF, amyloid, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or acute hyperthyroidism and those with NVAF over age 65 or NVAF and a CHADS2 risk factor. However, OAC is not recommended for NVAF patients < 65 years with none of the CHADS2 risk factors because the risk of stroke is very low in this group. See Figure 2: Antithrombotic Therapy for Stroke Prevention in AF/AFL.

In patients with device-detected (e.g., pacemaker) AF, there appears to be an association between duration of AF and risk of stroke/systemic embolism. There is expert agreement that OAC should be considered according to the CCS algorithm (CHADS-65; see Figure 2: Antithrombotic Therapy for Stroke Prevention in AF/AFL) when device- detected AF lasts longer than 24 hours, regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms. There is no consensus for optimal treatment for shorter episodes.

- All patients with valvular AF (mechanical valve or moderate to severe mitral stenosis) should be treated with warfarin.4,5 See BCGuidelines: Warfarin for target INR.

- Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are contraindicated in patients with valvular AF.4,5

- For patients with NVAF, use the CCS Algorithm (CHADS-65) to determine the optimal antithrombotic therapy. CHADS-65 complements the use of the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores, both of which estimate the annual risk of stroke. See Appendix D: Stroke Risk Assessment in Atrial Fibrillation – CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc Scores for these scores and stroke risk.

- DOACs are preferred over warfarin in NVAF because pooled data from randomized trials have shown that the risks of stroke/ systemic embolism, intracranial bleed and all-cause mortality are significantly reduced with DOAC compared with warfarin.6 See approved DOACs and their standard doses in BCGuideines: Direct Acting Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs).

- Antiplatelet therapy options include: ASA 81 mg daily alone, clopidogrel 75 mg daily alone, or ASA 81 mg daily combined with clopidogrel 75 mg daily, ticagrelor 60 mg bid, or rivaroxaban 2.5 mg bid, depending on clinical circumstance. Note – the antiplatelet therapy is provided primarily for the management of concomitant vascular disease and not as a stroke preventative therapy per se. See Appendix E: Management of Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with AF and CAD/PAD.

- Absence of symptoms (e.g., in subclinical AF) does not change management.

Special Considerations in Stroke Prevention

See BC Guidelines for details of OAC usage, including warfarin, DOAC and periprocedural management.

Cardioversion

- OAC for a minimum of 3 weeks is needed BEFORE planned cardioversion in the following patients:

- Valvular AF

- NVAF episode duration < 12 hour and recent (< 6 months) stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- NVAF episode duration 12 – 48 hours and CHADS2 score > 2

- NVAF episode duration > 48 hours

- OAC for a minimum of 4 weeks is needed AFTER cardioversion and then long-term anticoagulation should be managed according to CHADS-65.

Catheter or Surgical Ablation1,7,8

- Uninterrupted OAC is considered the standard of care for patients undergoing ablation for AF/AFL.

- Uninterrupted OAC typically means initiating OAC 3 – 4 weeks before the procedure, continuing OAC right up to the time of procedure (it is reasonable to hold 1 – 2 doses for DOACs before ablation), and reinitiating OAC 6 – 12 hours after the procedure.

- Post ablation OAC management:

- Continue OAC for at least 2 months after AF ablation.

- Thereafter, provide OAC according to the CCS algorithm (CHADS-65; see Figure 2: Antithrombotic Therapy for Stroke Prevention in AF/AFL) because the risk of stroke may not be sufficiently reduced even after successful ablation (i.e., achieving normal sinus rhythm). This is especially true for those with high thromboembolic risk profile.

- If OAC is indicated by CHADS-65 but patient prefers to stop, ongoing monitoring for AF recurrence is needed and consultation with specialist is recommended. Research is addressing optimal duration of OAC post ablation.

Coronary Artery Disease

- Patients with AF/AFL AND recent coronary stents may require combination OAC and antiplatelet therapy for a limited period following revascularization as directed by the interventional cardiologist.

- Patients with AF/AFL AND stable coronary or arterial vascular disease (e.g., greater than 1 year following revascularization) should receive antithrombotic therapy based on CHADS-65. Combination of ASA and OAC beyond 1 year is NOT recommended because it increases bleeding risk without the benefit of greater efficacy (See Appendix E: Management of Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with AF and CAD/PAD).

Frail Elderly

- Anticoagulant therapy is recommended for most frail elderly patients with AF/AFL. The net clinical benefit favours anticoagulation, even in those with higher risk of falls, as these patients are at higher risk of stroke and more likely to benefit from OAC than younger patients.

- It is estimated that patients with AF taking warfarin have to fall more than 295 times in 1 year for the risks of warfarin to outweigh its benefits. Fall risk alone should therefore not be a reason to withhold anticoagulation.9

- Attention should be paid to polypharmacy in elderly patients, because of high potential for drug-drug interactions. See BCGuidelines: Direct Acting Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs).

Patients Unable to Receive Anticoagulant Therapy or With History of Intracranial Hemorrhage

- Patients at moderate to high risk of stroke who have absolute contraindications for anticoagulation should be referred to assessment for possible left atrial appendage occlusion.

- Patients with history of intracranial hemorrhage while on OAC may or may not be able to resume OAC. Referral to a Stroke Neurologist for assessment is recommended.

Patients with high body weight or BMI > 40 kg/m2

- Increasing BMI is associated with a higher risk of bleeding but lower risk of stroke/systemic embolism.

- Recent studies have shown DOACs to be similarly effective and safer than warfarin for reduction of stroke and systemic embolism in these patients.

- For severely obese patients, an individualized approach (See BCGuidelines: Direct Acting Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)) to balance the efficacy and safety profile may be necessary.1,10

TOP

TOP

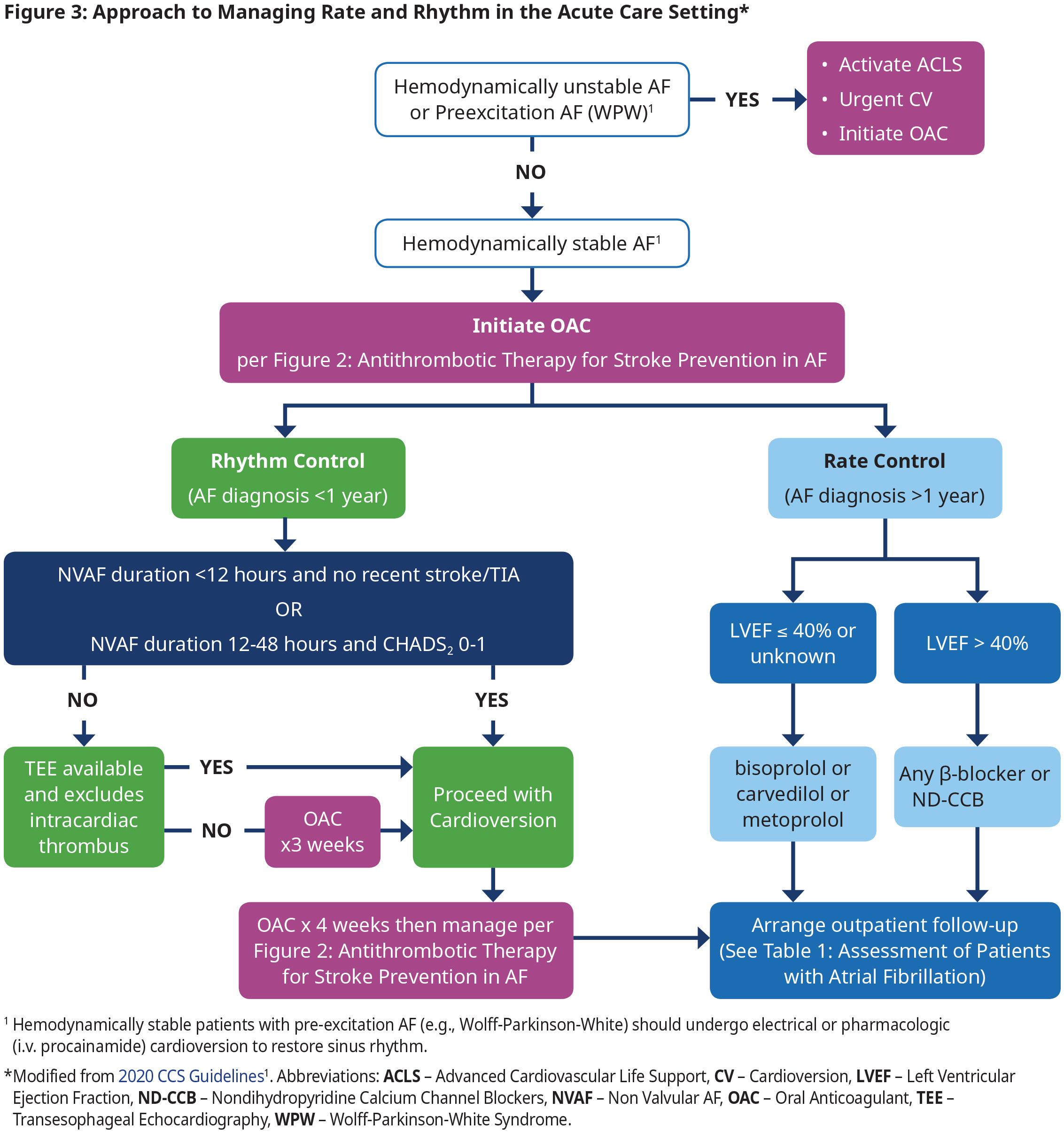

Management of Rate and Rhythm in An Acute Care Setting

Rhythm Control in Acute Care

- In those patients with recently diagnosed AF (within 1 year), an initial strategy of rhythm control is preferred as the first treatment strategy because it is associated with reduced cardiovascular death and reduced rates of stroke.11 However, antiarrhythmic drugs have not been associated with a beneficial effect on mortality and many have significant adverse effects.

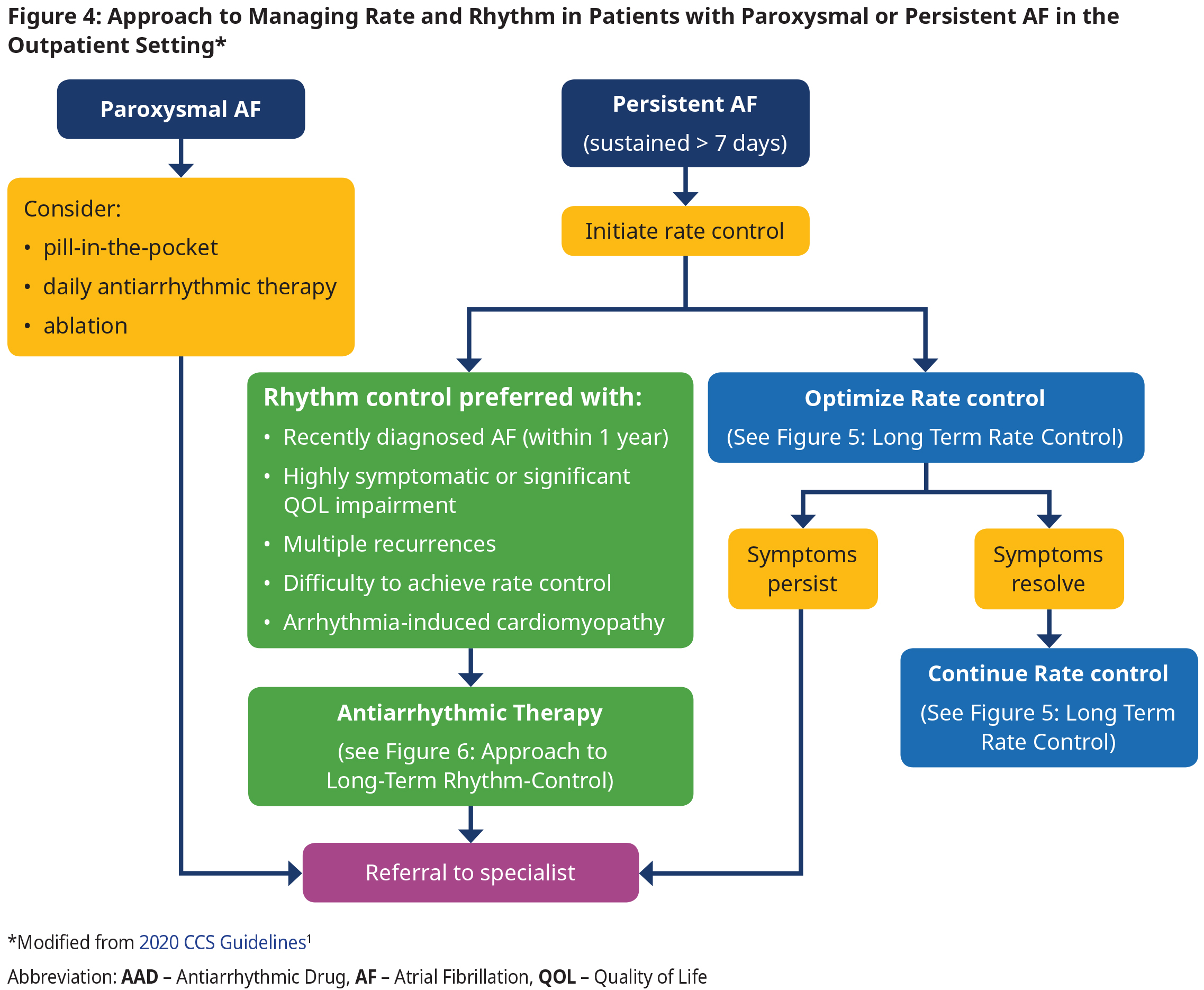

- In patients with established AF (duration > 1 year), multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between patients treated with a strategy with rate control vs rhythm control. In this group the decision to use each therapy should be made according to shared decision- making and taking into account patient preferences (see Figure 4: Approach to Managing Rate and Rhythm in Patients with Paroxysmal or Persistent AF in the Outpatient Setting).

- Electrical or pharmacological (i.v. procainamide) cardioversion can be used for sinus rhythm restoration in hemodynamically stable patients. Electrical cardioversion is more effective and is preferred if procedural sedation is available.

- Use of i.v. β-blockers, diltiazem, verapamil, digoxin, and amiodarone are contraindicated for acute management of pre-excitation AF (e.g., WPW) because of the potential to precipitate a life-threatening arrhythmia. See section WPW under special considerations.

Rate Control in Acute Care

- Titrate rate-controlling agents to achieve a target heart rate of ≤ 100 bpm at rest.1

- In patients with LVEF > 40%, there are no randomized long-term data to indicate a preference between a β-blocker and a non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (ND-CCB).

- Use caution when administering i.v. formulations of β-blockers, ND-CCBs or amiodarone because of risk of precipitating hypotension. Introduce oral formulations as soon as possible to avoid rebound tachycardia seen when i.v. formulation wears off.

Follow-Up after Acute Care Setting

- Determine if patient needs to be hospitalized (if highly symptomatic, co-existing acute/complex medical conditions, if adequate rate control cannot be achieved, or need for investigations not readily available in an outpatient setting).

- If hospitalization not required, then arrange medical follow-up in an outpatient setting, ideally within 7 – 14 days.

Management of Rate and Rhythm in the Outpatient Setting

- Patients with AF may present with or without symptoms (see Appendix C: Assessing Atrial Fibrillation Symptom Severity with the CCS-SAF Scale for symptom severity scale).

- Approach to rate and rhythm control in the outpatient/long term setting is dependent on

- type of AF (paroxysmal vs persistent),

- duration of AF,

- LV function, and

- patient symptoms and preferences.

- In those patients with recently diagnosed AF (within 1 year), an initial strategy of rhythm control is preferred as the first treatment strategy because it is associated with reduced cardiovascular death and reduced rates of stroke.11 However, antiarrhythmic drugs have not been associated with a beneficial effect on mortality and many have significant adverse effects.

- In those patients with established AF (duration > 1 year), RCTs have shown no significant difference in cardiovascular outcomes between patients treated with a strategy with rate control vs rhythm control.

- Referral to a specialist is recommended in those who remain symptomatic despite maximally tolerated rate control therapy.

- Catheter ablation is preferred to pharmacotherapy for AFL because of the relatively high success rate and low complication rate of the procedure.

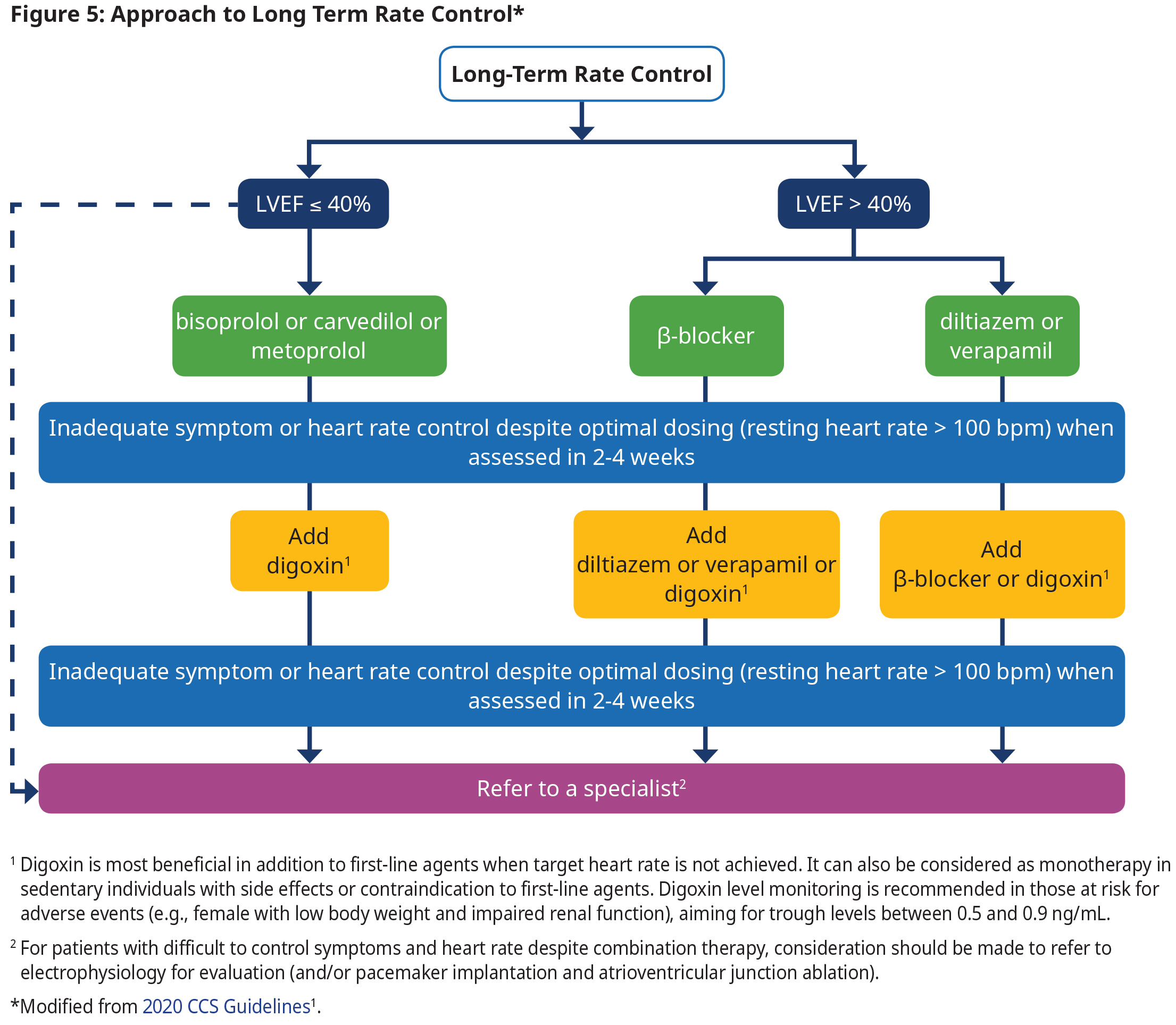

Long-term Rate Control

- Titrate rate-controlling agents to achieve a target heart rate of ≤ 100 bpm at rest.

- Patients who are unable to tolerate pharmacological therapy or who do not achieve target rate control should be referred for specialist consultation.

Long Term Rhythm Control

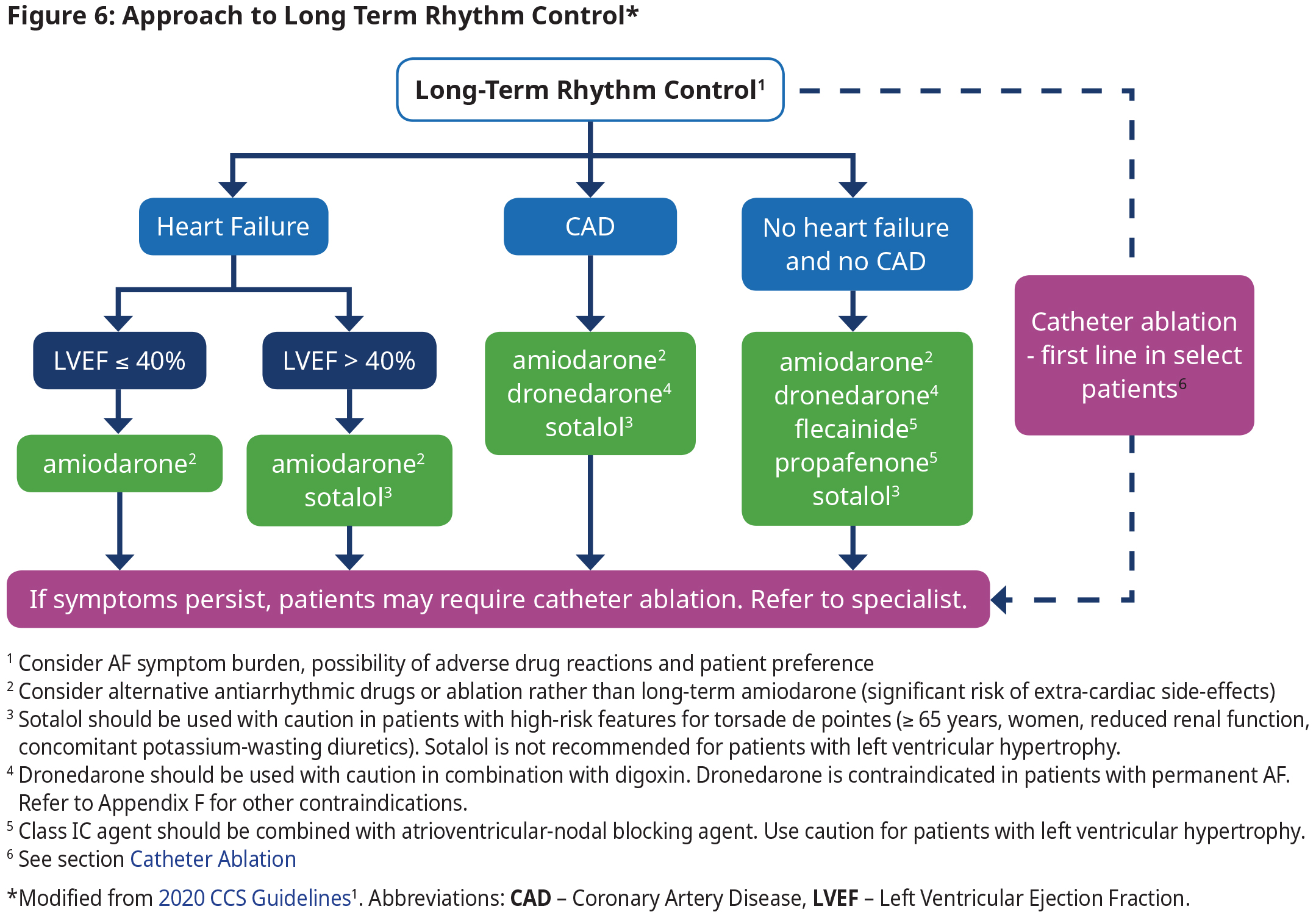

- The focus of rhythm control is on symptom relief, improving functional capacity and quality of life, and reducing health care utilization, and not necessarily the elimination of all AF episodes.

- Long-term oral antiarrhythmic therapy should not be continued in patients with permanent AF because antiarrhythmic drugs have not been associated with a beneficial effect on mortality and many have significant adverse effects.

- Consultation with specialists is recommended if antiarrhythmic therapy is being considered (See Figure 6: Approach to Long Term Rhythm Control). The choice of antiarrhythmic therapy is primarily driven by safety and tolerability because they have a relatively similar efficacy while all drugs have significant adverse effects.

- Consultation with specialists is recommended if antiarrhythmic therapy is being considered (See Figure 6: Approach to Long Term Rhythm Control). The choice of antiarrhythmic therapy is primarily driven by safety and tolerability because they have a relatively similar efficacy while all drugs have significant adverse effects. See Appendix F: Prescription Medication Tables for Atrial Fibrillation for dosage and therapeutic considerations.

Special Considerations in Arrhythmia Management

Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW)

- WPW is a pre-excitation syndrome in patients who have an additional accessory pathway (also called bundle of Kent) that directly connects the atria and ventricles, thereby allowing electrical activity to bypass the atrioventricular node, leading to "preexcitation" or earlier than usual activation of the His-Purkinje system.

- Rapid conduction of AF via accessory pathway is rare but can result in ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death.

- Use electrical or pharmacologic (using i.v. procainamide) cardioversion to restore sinus rhythm in hemodynamically stable patients.

- β-blockers, diltiazem, verapamil, digoxin, and amiodarone are contraindicated for acute management of pre-excitation AF because of the potential to precipitate a life-threatening arrhythmia.

- Catheter ablation is the treatment of choice for chronic management of pre-excitation AF.

- Current evidence shows that the cryoablation as a first therapy (vs. antiarrhythmic drugs) is associated with reduction in arrhythmia recurrence, healthcare utilization (hospitalization, ED visits, cardioversion) and improvement in quality of life for 3 years after the procedure.

- In patients with AFL, catheter ablation is preferred to pharmacotherapy because of the relatively high success rate and low complication rate of the procedure.

- Select patients with AF who might benefit from catheter ablation as first-line therapy include:

- Heart failure or reduced ejection fraction, particularly those with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.

- Treatment-naïve patients who are younger without significant comorbidities.

Management of Comorbid Conditions

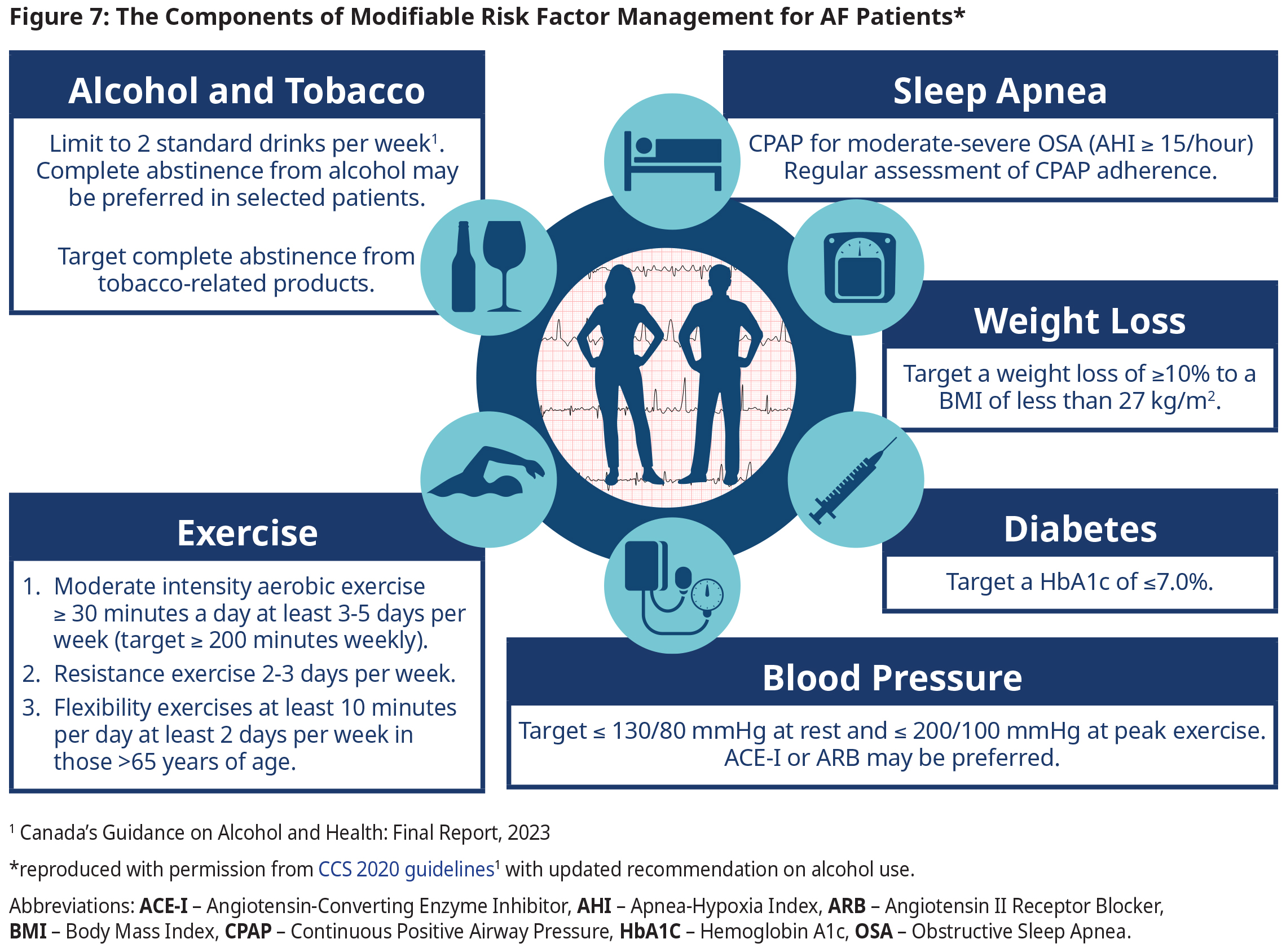

- In addition to the key modifiable risk factors and treatment targets outlined in Figure 7: The Components of Modifiable Risk Factor Management for AF Patients, consideration should be given to manage co-existing conditions consistent with contemporary guideline recommendations.

- Please refer to other BC guidelines on Hypertension, Diabetes Care, and Obstructive Sleep Apnea.

Indications for Potential Specialist Referral

- AF in a patient aged ≤ 60 years with no evidence of associated cardiopulmonary or other comorbid disease.

- Those with an underlying electrophysiological disorder (e.g., pre-excitation/WPW) or those with co-existing heart failure.

- Patients with paroxysmal AF or AFL.

- When pharmacologic therapy fails to ameliorate AF-related symptoms and/or improve quality of life.

- Patients with relative or absolute contraindication for anticoagulants. Some of these patients might be candidates for left atrial appendage occlusion.

- Other specialist clinics of value to AF patients include AF clinics (AF clinics require ECG documentation before accepting patients), Diabetes clinics, Heart Failure clinics, Rapid Access Stroke clinics.

References

- The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation - Canadian Journal of Cardiology [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 16]. Available from: https://www.onlinecjc.ca/article/S0828-282X(20)30991-0/fulltext

- Cheung CC, Nattel S, Macle L, Andrade JG. Management of Atrial Fibrillation in 2021: An Updated Comparison of the Current CCS/CHRS, ESC, and AHA/ACC/HRS Guidelines. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2021 Oct 1;37(10):1607–18.

- Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The Clinical Profile and Pathophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation Research. 2014 Apr 25;114(9):1453–68.

- Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, Granger CB, Kappetein AP, Mack MJ, et al. Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves. N Engl J Med. 2013 Sep 26;369(13):1206–14.

- Connolly SJ, Karthikeyan G, Ntsekhe M, Haileamlak A, El Sayed A, El Ghamrawy A, et al. Rivaroxaban in Rheumatic Heart Disease–Associated Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022 Sep 15;387(11):978–88.

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. The Lancet. 2014 Mar 15;383(9921):955–62.

- Nogami A, Harada T, Sekiguchi Y, Otani R, Yoshida Y, Yoshida K, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Minimally Interrupted Dabigatran vs Uninterrupted Warfarin Therapy in Adults Undergoing Atrial Fibrillation Catheter Ablation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Apr 19;2(4):e191994.

- Nakamura K, Naito S, Sasaki T, Take Y, Minami K, Kitagawa Y, et al. Uninterrupted vs. interrupted periprocedural direct oral anticoagulants for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a prospective randomized single-centre study on post-ablation thrombo-embolic and haemorrhagic events. EP Europace. 2019 Feb 1;21(2):259–67.

- Seelig J, Pisters R, Hemels ME, Huisman MV, ten Cate H, Alings M. When to withhold oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation – an overview of frequent clinical discussion topics. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2019 Sep 17;15:399–408.

- Malik AH, Yandrapalli S, Shetty S, Aronow WS, Jain D, Frishman WH, et al. Impact of weight on the efficacy and safety of direct-acting oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. EP Europace. 2020 Mar 1;22(3):361–7.

- Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, Brandes A, Eckardt L, Elvan A, et al. Early Rhythm-Control Therapy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct;383(14):1305–16.

- Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001 Jun 13;285(22):2864–70.

- Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: nationwide cohort study - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2022 Aug 12]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21282258/

- Lane DA, Lip GYH. Use of the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED Scores to Aid Decision Making for Thromboprophylaxis in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2012 Aug 14;126(7):860–5.

Abbreviations:

AAD Antiarrhythmic Drug

ACE-I Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor

ACLS Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support

AF Atrial Fibrillation

AFL Atrial Flutter

AHI Apnea Hypoxia Index

ARB Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker

ASA Acetylsalicylic Acid

AVJ Atrioventricular junction

BMI Body Mass Index

CBC Complete Blood Count

CCS Canadian Cardiovascular Society

CCS-SAF CCS Symptoms of Atrial Fibrillation

CKD Chronic Kidney Disease

CPAP Continuous Positive Airway Pressure

CV Cardioversion

DCCV Direct Current Cardioversion

EF Ejection Fraction

HbA1C Hemoglobin A1c

HF Heart Failure

HFrEF Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

HTN Hypertension

INR International Normalized Ratio

LVEF Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

ND-CCB Nondihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers

NVAF Non-Valvular AF

OAC Oral Anticoagulant

OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea

PAD Peripheral Artery Disease

QOL Quality of Life

TEE Transesophageal Echocardiography

TIA Transient Ischemic Attack

TSH Thyroid Stimulating Hormone

WPW Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

Practitioner Resources

RACE: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program – www.raceconnect.ca

RACE means timely telephone advice from specialist for Physicians, Medical Residents, Nurse Practitioners, Midwives, all in one phone call. Monday to Friday 0800 – 1700

Online at www.raceapp.ca or though Apple or Android mobile device. For more information on how to download RACE mobile applications, please visit www.raceconnect.ca/race-app/

Local Calls: 604–696–2131 | Toll Free: 1–877–696–2131

For a complete list of current specialty services visit the Specialty Areas page.

Pathways – PathwaysBC.ca

An online resource that allows GPs and nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. In addition, Pathways makes available hundreds of patient and physician resources that are categorized and searchable.

General Practice Services Committee – www.gpscbc.ca

- Practice Support Program: offers focused, accredited training sessions for BC physicians to help them improve practice efficiency and support enhanced patient care.

- Chronic Disease Management and Complex Care Incentives: compensates GPs for the time and skill needed to work with patients with complex conditions or specific chronic diseases.

Health Data Coalition: hdcbc.ca

An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist you in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing. HDC data can graphically represent patients in your

practice with chronic kidney disease in a clear and simple fashion, allowing for reflection on practice and tracking improvements over time.

HealthLinkBC: healthlinkbc.ca

HealthLinkBC provides reliable non-emergency health information and advice to patients in BC. Information and advice on managing Diabetes in several languages is available by telephone, website, a mobile app, and a collection of print resources. People can speak to a health services navigator, registered dietitian, registered nurse, qualified exercise professional, or a pharmacist by calling 8-1-1 toll-free in B.C, or 7-1-1 for the deaf and hard of hearing.

BCGuidelines, www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines – Cardiovascular Disease – Primary Prevention; Diabetes Care, Heart Failure – Diagnosis and Management; Hypertension – Diagnosis and Management, Obstructive Sleep Apnea.

Heart and Stroke Foundation – British Columbia and Yukon, www.heartandstroke.bc.ca

Canadian Stroke Network, www.canadianstrokenetwork.ca

Stroke Services BC, www.phsa.ca/AgenciesAndServices/Services/stroke-services-bc.htm

Patient Resources

HealthLinkBC: Atrial Fibrillation

Thrombosis Canada: Atrial Fibrillation

Diagnostic Codes

427.3 [I48] – Cardiac Dysrhythmia

Appendices

- Appendix A: Types of Atrial Fibrillation (PDF, 91KB)

- Appendix B: Risk Factors for the Development of AF (PDF, 90KB)

- Appendix C: Assessing Atrial Fibrillation Symptom Severity with the CCS-SAF Scale (PDF, 90KB)

- Appendix D: Stroke Risk Assessment in Atrial Fibrillation: CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc Score (PDF, 92KB)

- Appendix E: Management of Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with AF And CAD/PAD (PDF, 96KB)

- Appendix F: Prescription Medication for Atrial Fibrillation (PDF, 119KB)

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee in collaboration with the Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services and adopted under the Medical Services Act and the Laboratory Services Act.

For more information about how BC Guidelines are developed, refer to the GPAC Handbook available at BCGuidelines.ca: GPAC Handbook.

THE GUIDELINES AND PROTOCOLS ADVISORY COMMITTEE

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact InformationGuidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee E-mail: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the guidelines) have been developed by the guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |