Chronic Kidney Disease – Diagnosis and Management

Effective Date: July 23rd, 2025

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Background

- Evaluation for the cause(s) of CKD

- Screening

- Diagnosis

- Classification and Staging of CKD

- Management

- Non-pharmacological Management

- Pharmacological Management

- Special Populations

- Advance Care Planning

- Methodology

- Resources

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for the investigation, evaluation, and management of adults at risk of/or with known chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Key Recommendations

- Screen high-risk patients (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, family history, and those with a history of acute kidney injury) using estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) and urine AlbuminCreatinine Ratio (ACR). Confirm abnormal test results with a repeat measurement and obtain urinalysis (microscopic).

- Determine likely cause of kidney disease where possible. This has important implications for determining risk of End Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD)/Kidney Failure and other complications.

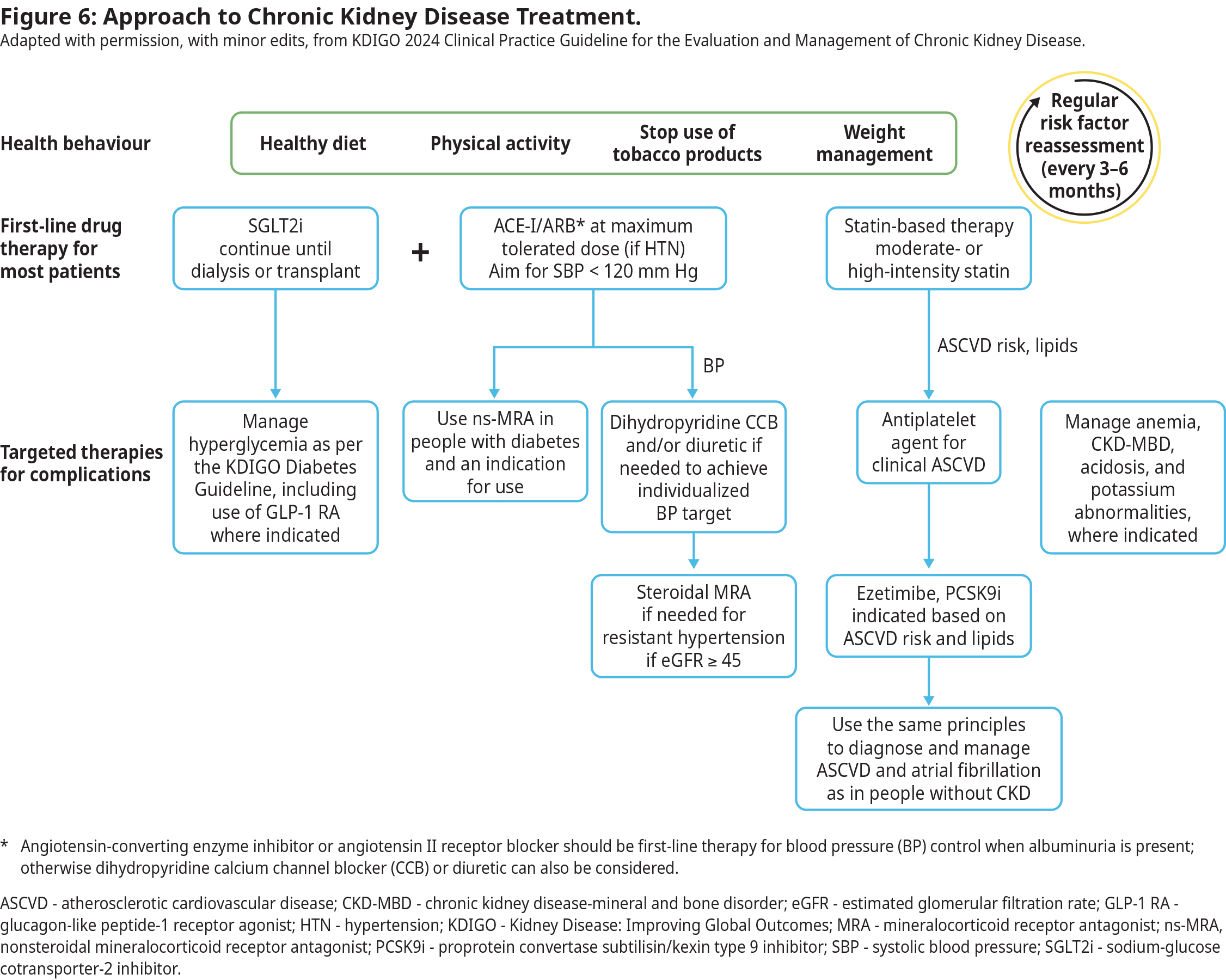

- Use disease modifying drugs to control hypertension and proteinuria that prevent or postpone kidney function decline.

- All patients with CKD: Initiate an ACE inhibitor (ACE-I) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

- [NEW] Patients with CKD and uACR ≥ 20 mg/mmol: In addition to ACE-I/ARB, start a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i), unless contraindicated.

- [NEW] Patients with CKD and heart failure: In addition to ACE-I/ARB, start a SGLT2i, unless contraindicated.

- [NEW] Patients with CKD and type 2 diabetes: In addition to ACE-I/ARB and SGLT2i, include a non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (ns-MRA) and a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) to optimize renal and cardiovascular outcomes.

- Prescribe statins for CKD patients ≥ 50 yrs and for those 18-49 yrs with cardiovascular risk factors.

- Hold ACE-I, ARB, SGLT2i, and diuretics if patient has acute illness with dehydration, with a plan to restart.

- To assist in determining the need for and timing of referral, obtain advice from local internists, nephrologists or RACE.

Background

CKD is defined as abnormalities of kidney structure or function that are present for a minimum of 3 months, with implications for health.1 CKD markedly increases the risk of adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular mortality, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral artery disease, acute kidney injury, and kidney failure requiring replacement therapy (dialysis or transplantation).2 CKD increases the risk of all-cause mortality.2–4 Most patients with CKD die from other comorbidities before they progress to kidney failure.1 Medications are now available that improve mortality and reduce major kidney disease events.

In 2022/23, over 240,000 British Columbians were identified as having CKD (4.1% of the adult population),5 which is lower than the expected 10% of adult population.6 This underscores the need for enhanced education about CKD identification and awareness.

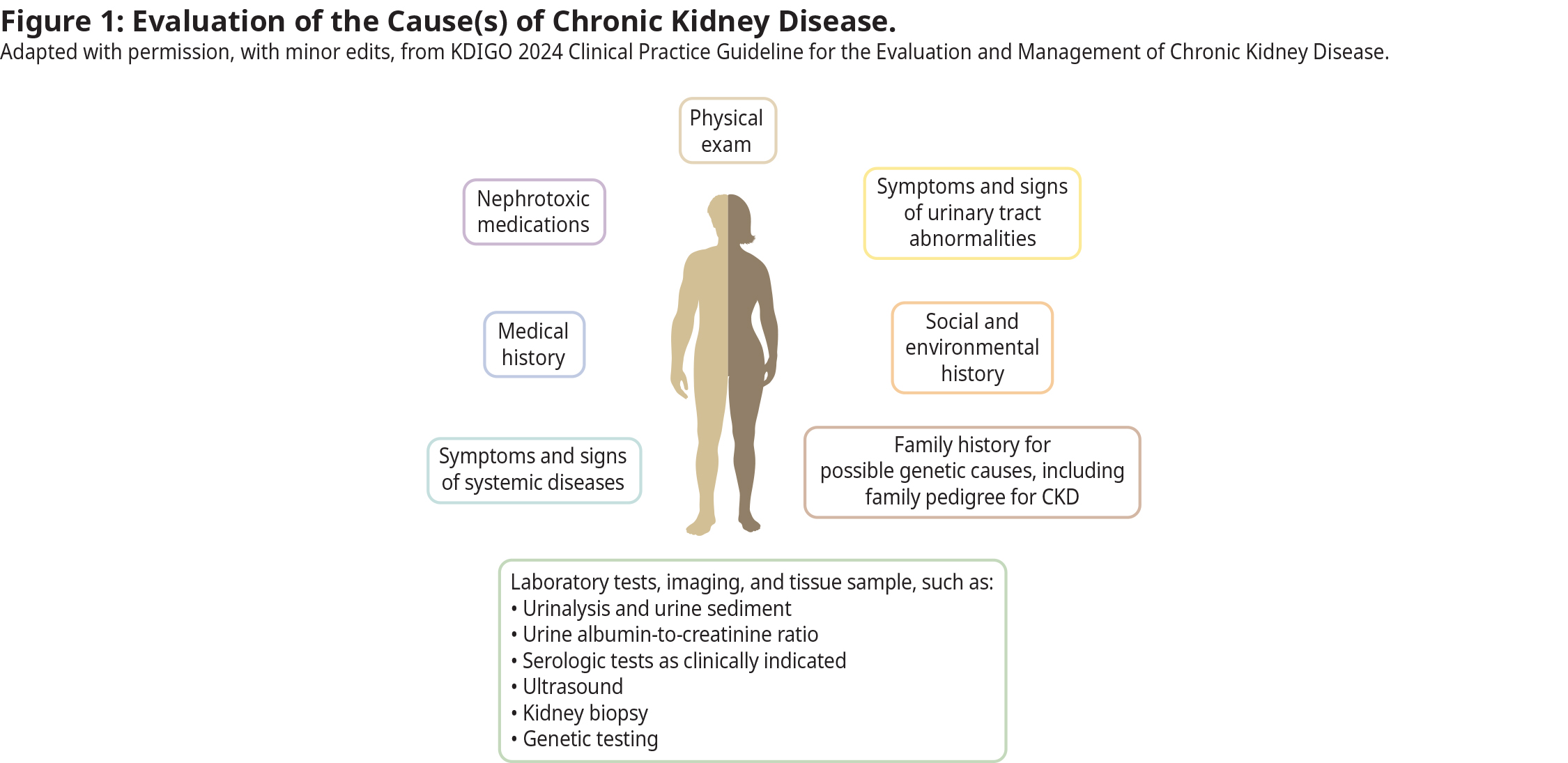

Evaluation for the cause(s) of CKD

A comprehensive approach (Figure 1) is recommended to establish the cause of CKD such as clinical context, personal and family history, social and environmental factors, medications, physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging, and genetic and pathologic diagnoses.1,7 The two most common causes of CKD are hypertension and diabetes, which often co-exist.

Even if a cause seems obvious (e.g., diabetes), the possibility of other diagnoses, including underlying primary kidney disorder (e.g., glomerulonephritis) should be considered in all patients, and especially those with:

- Abnormal urinalysis, (e.g., proteinuria, hematuria, cellular casts). Note: Hyaline casts are normal. See BC Guidelines: Workup of Microscopic Hematuria guideline

- Decline in eGFR > 10-15% per year despite correction of reversible precipitants (e.g., volume contraction, febrile illness, medications)

- Constitutional symptoms suggesting systemic illness (e.g., lupus nephritis, heart failure, HIV, liver disease, and dysproteinemias)

- Sudden onset or severe worsening of symptoms (e.g., edema unrelated to heart or liver disease)

Screening

Consider screening individuals with these common risk factors:

- First degree family history of kidney disease

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Cardiovascular disease

- Prior acute kidney injury

- Check eGFR and urine ACR once every 1-2 years, depending upon clinical circumstances (e.g., annual screening for those with diabetes, or who have had a cardiovascular event). Note: Older age alone is not a reason for screening.

Diagnosis

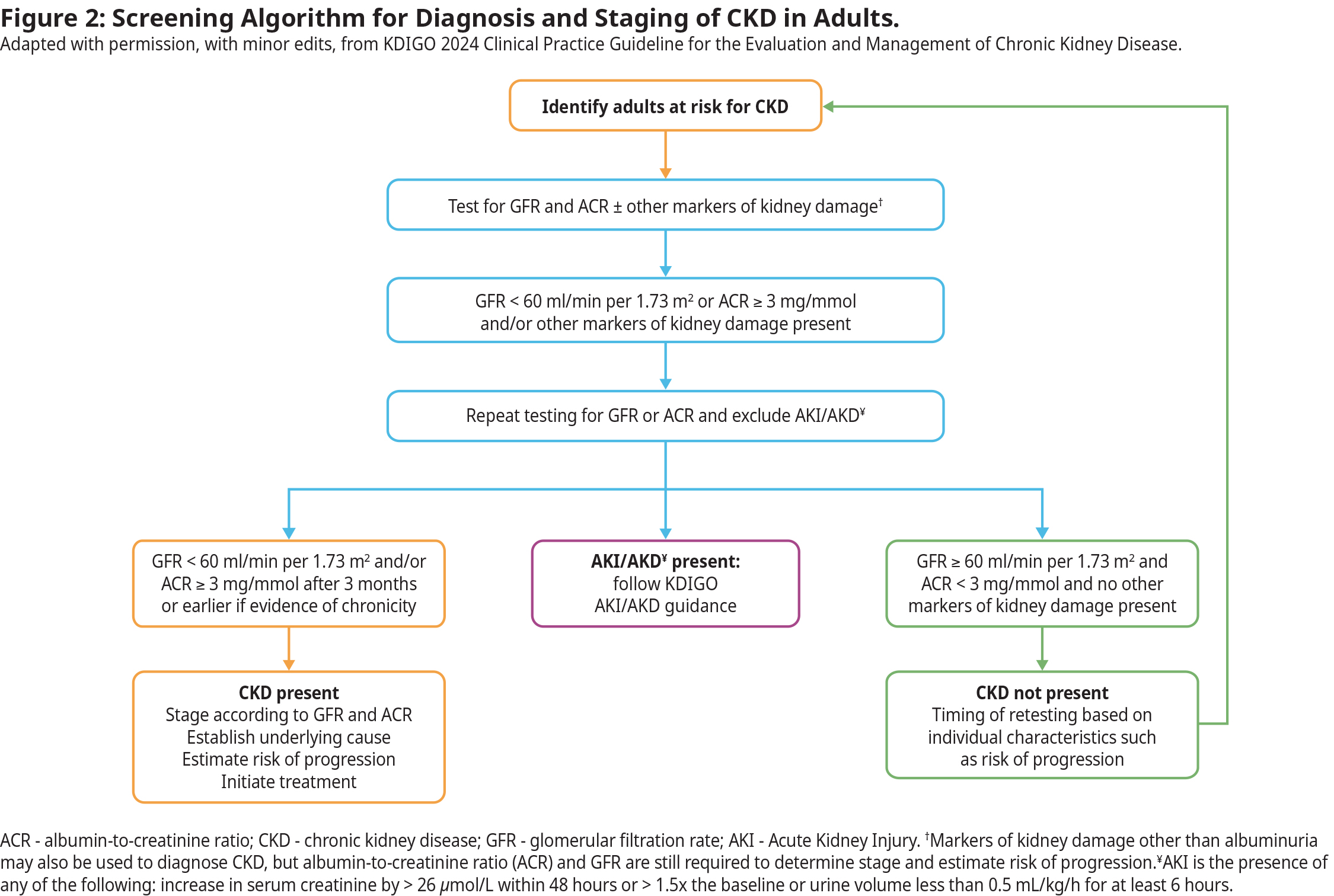

CKD is diagnosed when eGFR and/or urine ACR are abnormal and present for at least 3 months. Therefore, it cannot be diagnosed with one isolated abnormal measurement. Figure 2 outlines the recommended diagnostic and staging algorithm. Other markers of kidney damage include urine abnormalities (e.g., hematuria), structural abnormalities on imaging studies (e.g., polycystic kidneys) or histological findings on kidney biopsy.

Estimated GFR (eGFR) Values and Interpretation

- Values of < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 which are present for ≥ 3 months are diagnostic of CKD.

- For patients with a new or unexpected eGFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or a significant change in eGFR, repeat testing should be conducted within 1-2 weeks, depending on the severity and clinical context, to confirm stability or identify rapid deterioration.

- Initial values of eGFR between 50-60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and the absence of other markers of kidney disease (albuminuria, hematuria, structural abnormalities) may not indicate CKD, and need to be contextualized within trends over time.

Caveats of Interpreting eGFR

- eGFR is calculated from serum biomarkers such as creatinine. eGFR is an estimated value that assumes a steady state of the biomarker. All labs in BC automatically report eGFR when creatinine is ordered.

- In hospitalized patients or patients with AKI, fluctuations in creatinine make eGFR unreliable. In these circumstances, creatinine values and changes in creatinine (not eGFR) over time should be used to guide management.

- eGFR may be unreliable in extremes of muscle mass, while on certain diets (e.g., very high or very low protein), or when medications that interfere with the excretion of creatinine are used (e.g., trimethoprim, fenofibrate).1 More accurate markers (e.g., Cystatin C) are being introduced in clinical care, however, not currently available in BC.

- As a general rule, eGFR can be used to guide outpatient drug dosing even if the references use creatinine clearance.

- Please discuss with a Nephrologist or contact RACE when accuracy of GFR may affect clinical decision-making (e.g., nephrotoxic drugs).

Urine ACR Values and Interpretation

- Urine ACR is the preferred method to screen for protein in the urine.

- Urine ACR elevation ( ≥ 3.0 mg/mmol) on serial testing ( ≥ 2 elevated results out of 3 tests over a 4- to 12-week period) is abnormal.

- In most cases, 24-hour urine collections are not necessary to assess protein excretion.

- If laboratory testing of urine ACR and protein/creatinine ratios is unavailable, dipstick protein measurements can be performed.

- Urine ACR may be transiently elevated in some patients due to acute illness, vigorous exercise, poorly controlled hypertension or poorly controlled blood glucose. Repeat testing should be done after correcting the transient factor, using a first morning urine sample, if possible, to ensure a concentrated urine that better reflects the albumin/creatinine ratio.

- See Appendix A for interpretation of ACR values

Urinalysis (including urine microscopy)

- Significant abnormalities include persistent red blood cells (RBC) or white blood cells (WBC) in the absence of infection or instrumentation, and the presence of cellular casts.

- Persistent urine test abnormalities, (presence of WBCs, RBCs, non-hyaline casts, and/or protein or albumin) even with eGFR values ≥ 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 suggest kidney disease.

- Urine microscopy should be collected at the laboratory as the sample must be analysed within 2-3 hours. See BC Guidelines: Workup of Microscopic Hematuria.

Imaging

Renal imaging (kidney and bladder) is necessary to assess for structural abnormalities and aid in determining the etiology of CKD. Renal ultrasound (kidney and bladder) is a reliable test and typically most accessible. CT or MRI may provide more detailed information, if needed.

- Ultrasound should be performed or repeated in the following cases:

- Obstructive urinary symptoms or those with suspicion of benign prostatic hypertrophy

- Unexplained microscopic or macroscopic hematuria

- Family history of structural kidney disease (e.g., polycystic kidney disease)

Classification and Staging of CKD

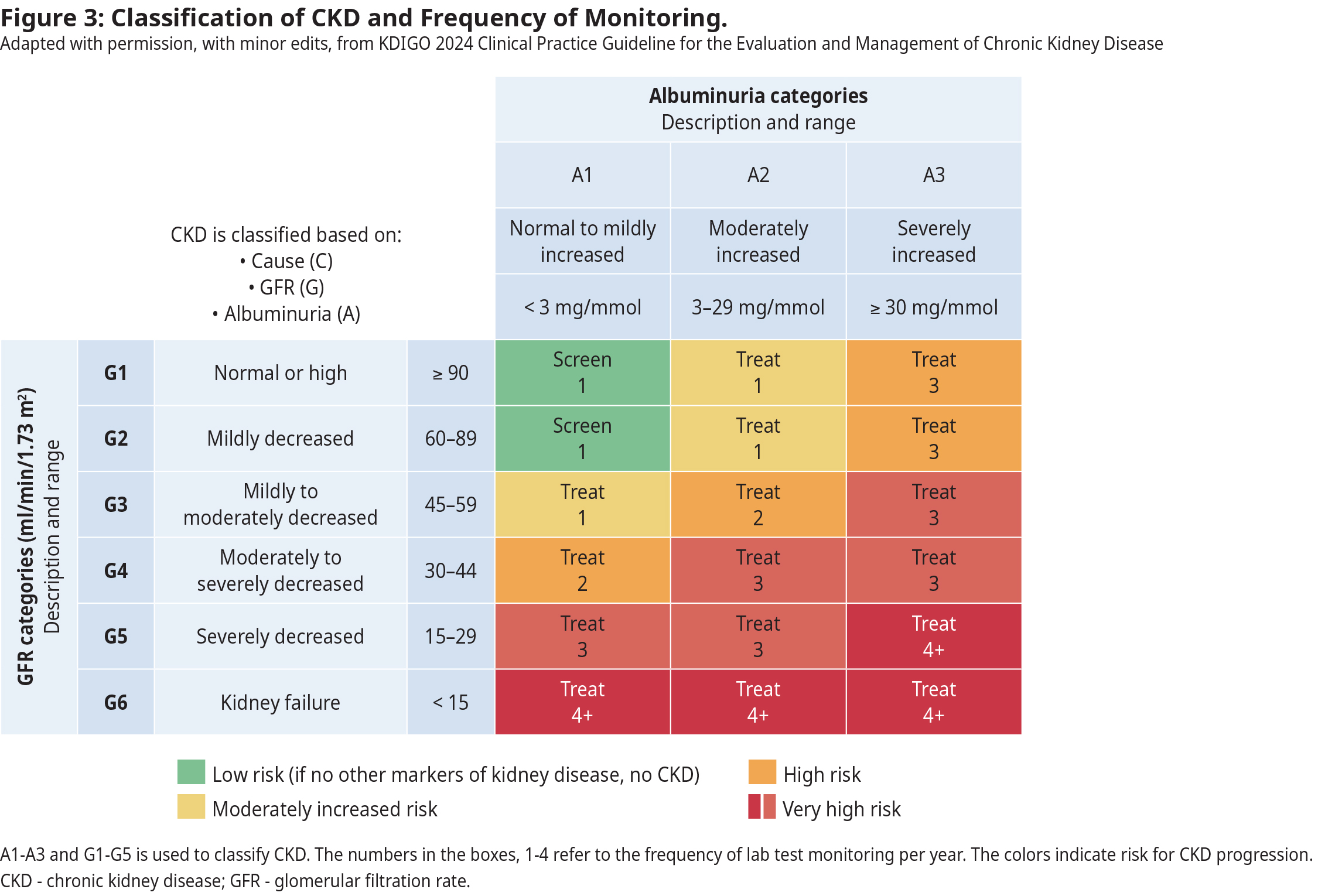

Figure 3 summarizes the classification and staging of CKD based on CGA: Cause (C), eGFR value (G1–G5) (G), and degree of albuminuria (A1–A3) (A). CGA classification also outlines the recommended frequency of eGFR and urine ACR monitoring. Staging is important for care planning and medical management. Patient age, ethnicity, disease cause, current eGFR and proteinuria levels also may impact outcomes.

Risk Calculators for Kidney Failure and CV events

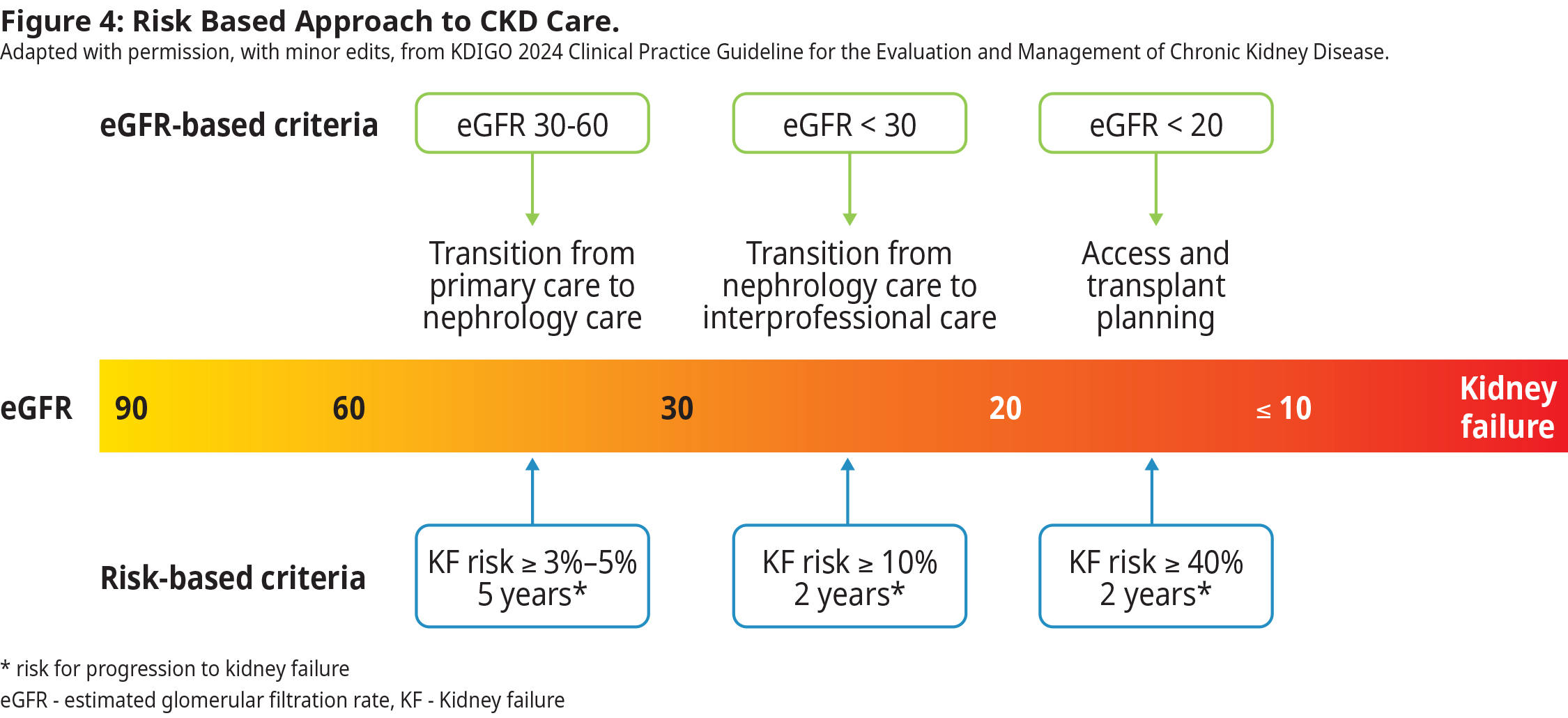

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) is recommended to estimate a patient’s 2- and 5-year risk of progression to kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation, in the absence of intervention. The basic KFRE uses 4 variables (age, sex, eGFR, urine ACR) to calculate risk. It is validated in those with eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. For adults with eGFR > 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, there are other risk prediction models using eGFR and urine ACR. The risk is modifiable. Based on the risk of progression to kidney failure, patients may be managed in primary care or prioritized for referral. See Figure 4 showing eGFR and KFRE risk criteria and recommendations for referral and treatment planning.

For cardiovascular risk prediction, use of validated tools developed specifically for adults with CKD such as QRISK3, PREVENT is recommended. Further details on risk determination are available on the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD management guideline.

Management

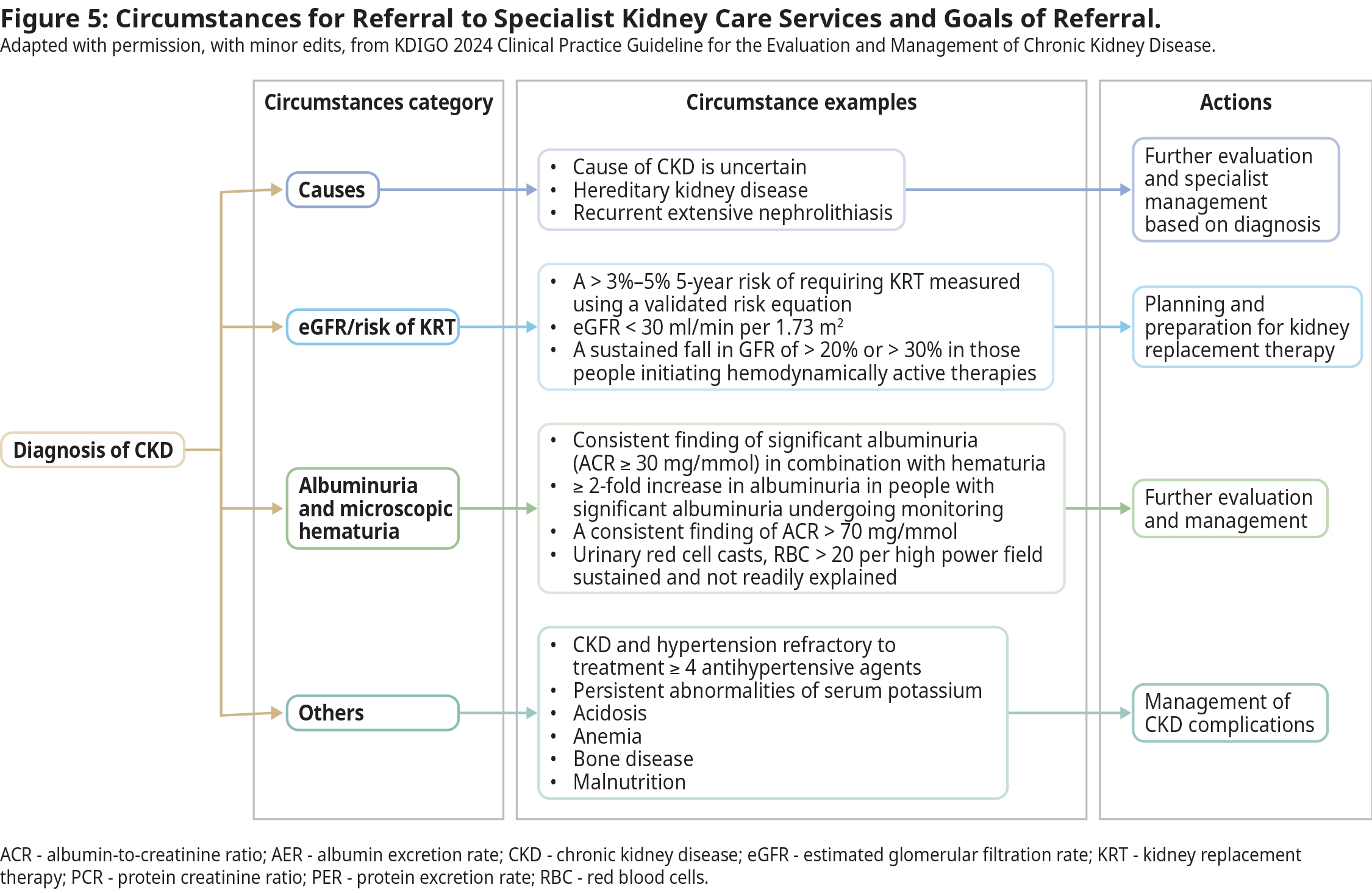

Many instances of newly identified CKD can be followed and managed in primary care but sometimes, early specialist collaboration is needed. Figure 5 outlines some clinical scenarios requiring specialist referral.

The cause of kidney disease (e.g., polycystic kidney disease, glomerulonephritis, diabetes) can affect the rate at which kidney disease worsens. Management of hypertension, proteinuria, and use of disease modifying drugs can prevent or postpone kidney function decline.1 This underlines the importance of early detection, evaluation, changes to health behaviors, and appropriate management of individuals with kidney disease.

Indications for Urgent and Priority Referrals

Urgent referral indicated (urgent concerns should trigger a conversation with nephrologist):

- Presence of active urine sediments (red blood cell casts or cellular casts ± protein), especially when associated with reduced eGFR

- AKI in absence of readily reversible cause (e.g., volume depletion, NSAIDs)

- Abrupt, sustained fall in eGFR

- eGFR < 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2

- Nephrotic syndrome ( > 300 mg/mmol urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, < 30 g/L serum albumin, edema, hyperlipidemia, lipiduria)

Priority referral indicated (patient to be seen in a timely fashion):

- eGFR < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2

- Unexplained persistent urine ACR > 30-70 mg/mmol, regardless of eGFR (e.g., in absence of diabetes or HTN)

- Progressive CKD, with eGFR decline > 5 mL/min per 1.73 m2 /year

- Diabetes and evidence of CKD with eGFR < 45 mL/min per 1.73 m2, urine ACR > 30 mg/mmol

Recommended items to be included in referral package:

- Comorbidities (especially cardiovascular)

- Medications

- CBC

- Electrolytes (Na, K, Cl, HCO3), calcium

- Creatinine/eGFR (include current value and any historical values available)

- Urinalysis and urine microscopy

- Urine ACR

- Kidney ultrasound – not required prior to submitting referral, but recommend it be arranged with result sent to specialist when completed

Referral Resources:

- Use PathwaysBC to see the list of specialists and their wait times

- Real-time communication with local specialists (or RACE) can provide rapid advice for urgent cases and timely advice and facilitate the most appropriate mechanism of referral.

- To locate kidney clinics in the region, use the BC Renal website.

A urology consult is more appropriate than nephrology in the following scenarios:

- Kidney mass

- Gross hematuria

- Enlarged prostate

- Obstruction

- Large symptomatic or obstructing kidney stone

Non-pharmacological Management

Patients with CKD require a comprehensive treatment strategy to reduce risks of progression and associated complications. They benefit from multidisciplinary teams who can support them to make beneficial changes. This may include addressing diet, smoking and physical activity, and understanding of medications. It may also help address the uncertainty and emotional distress.

Evidence suggest an important role of diet, including avoidance of excessive sodium and protein intake, which can cause or worsen glomerular hyperfiltration.8 Refer to diet information sheets provided by BC Renal intended for use by kidney patients. Consider consulting a renal dietitian through BC Dieticians.

Patients with CKD should be encouraged to engage in physical activities in line with their health and capacity, aiming to meet the KDIGO guideline recommendation of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous aerobic (cardio) activity per week.1

Support patient self-management with the means available in your community. Promotion of healthy lifestyles can prevent CKD in people at risk and help delay progression.

Pharmacological Management

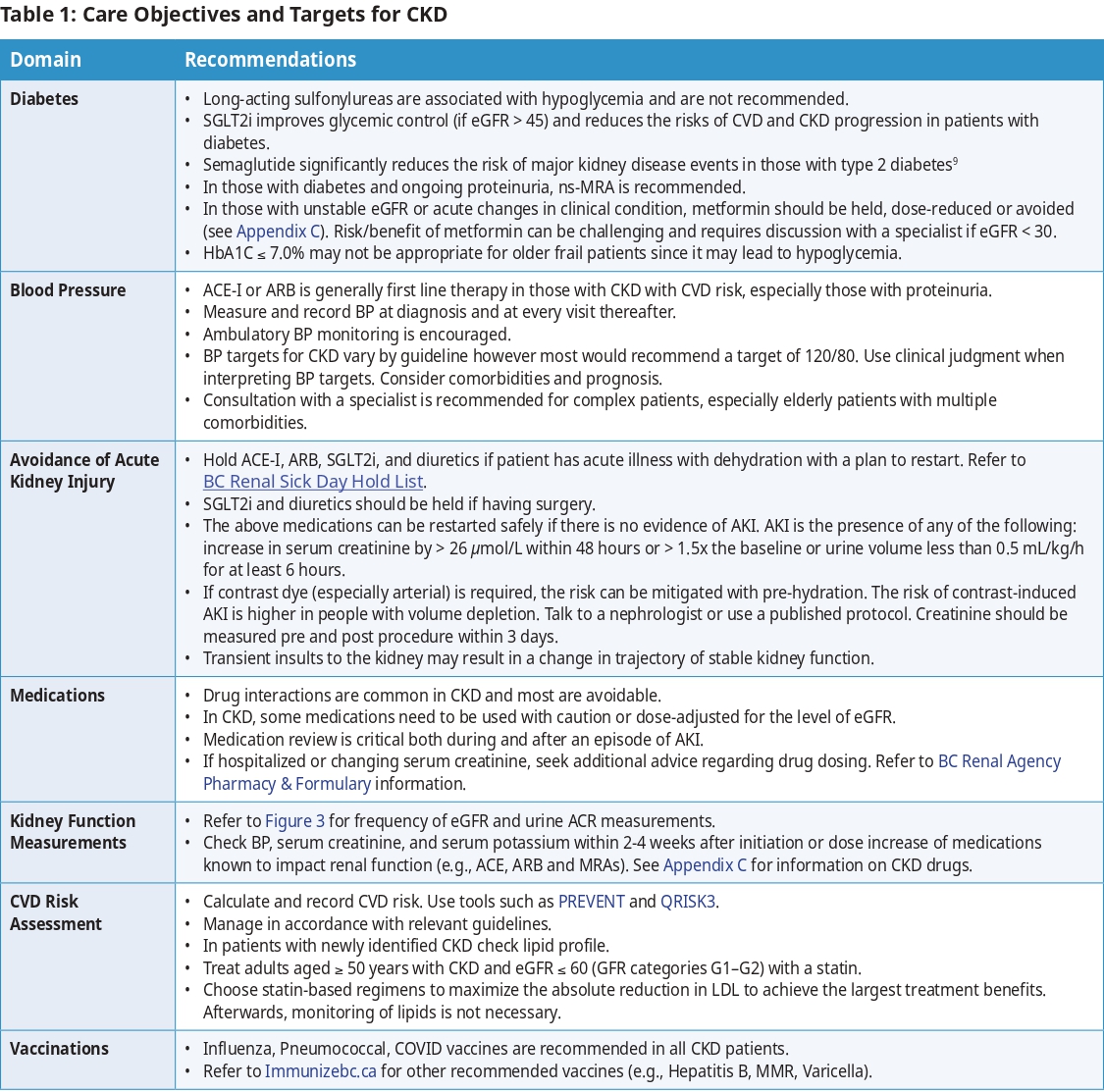

Figure 6 outlines an approach to pharmacological treatments commonly used in patients with CKD, including targeted therapies for specific conditions, such as diabetes. More details and cautions on management of these co-morbidities are in Table 1.

Special Populations

Elderly and Frail

Older adults make up the largest group with advanced CKD and require individualized care. Creatinine-based eGFR may overestimate kidney function due to lower muscle mass, increasing the risk of drug overdosing—consider alternative assessments and adjust medications accordingly. Less intensive BP and A1C targets are often necessary to reduce falls, hypotension and hypoglycemia. For those with frailty or low muscle mass, higher protein and calorie intake may be needed; refer to a renal dietitian for guidance.

Pregnancy and Reproductive Health

Although CKD is associated with decreased fertility, pregnancy is possible at all stages of CKD.1 People with CKD are at risk for adverse pregnancy-associated outcomes, including progression of their underlying CKD, a flare of their kidney disease, and pregnancy complications including pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, and small for gestational age infant.1 Those who have pre-eclampsia are at increased risk for CVD and CKD later in life, and should be assessed for both. All persons with CKD of reproductive age should receive counselling with respect to safe and effective contraception and options/optimization for pregnancy, if desired.

Transgender Population

The existing eGFR equations use sex as a binary variable. Therefore, in people who are transgender, gender diverse, or nonbinary, where a person’s gender identity is different from their sex assigned at birth, and/or they are taking gender affirming hormone therapy, the eGFR may be less accurate.1 Conversation with a nephrologist or a laboratory specialist is recommended.

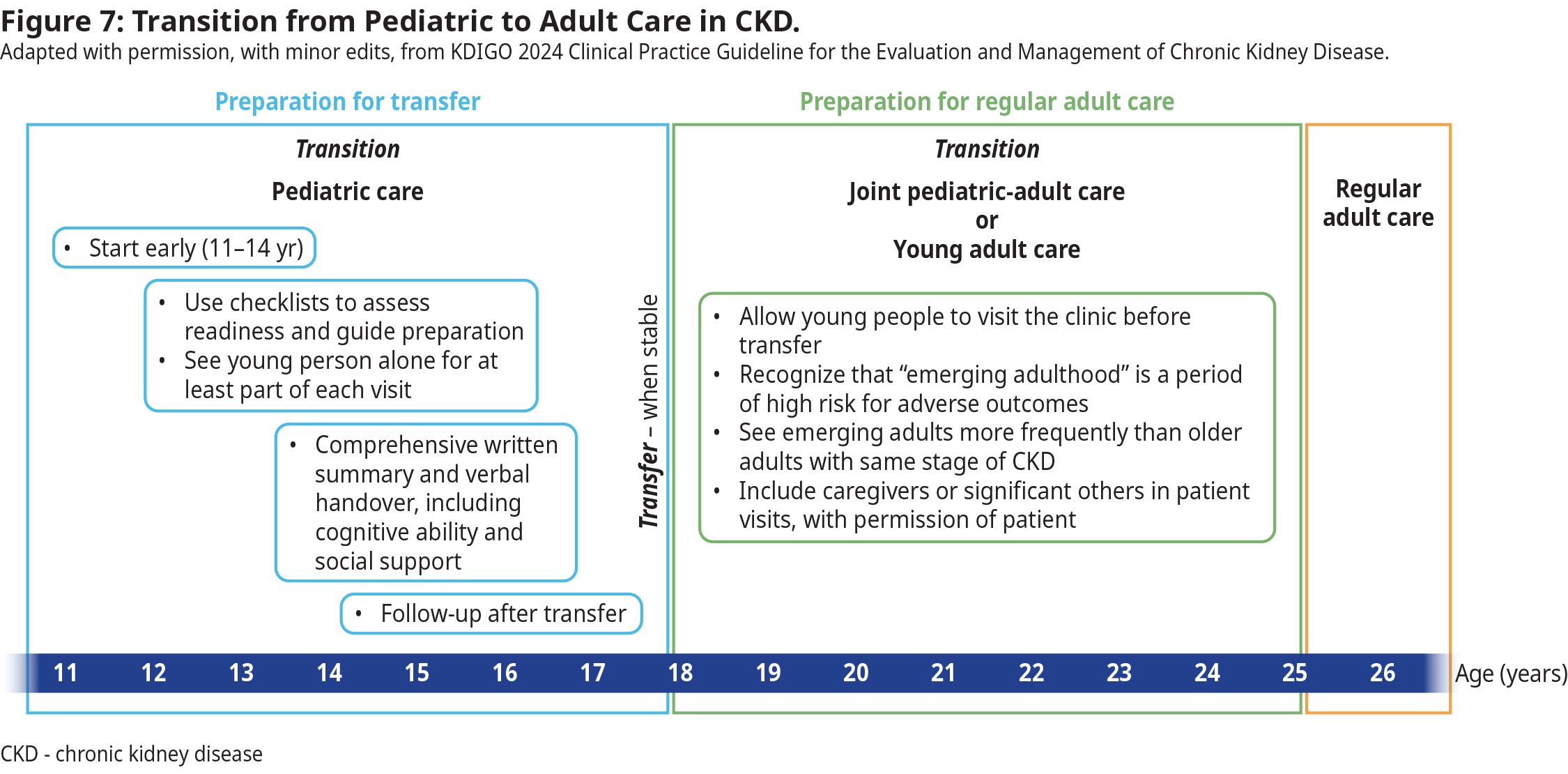

Transition of Care for Pediatric Patients into Adult Care

Coordination with pediatric nephrology to enable transition over a period of 12-18 months minimum is recommended. Start preparing patient at 11-14 yrs of age for transfer to adult-oriented care.

Indigenous Populations

Indigenous Populations

Indigenous people are at higher risk of CKD, irrespective of diabetic status, due to other multiple risk factors. These include biological reasons (e.g., inherited diseases, systemic inflammatory conditions, premature birth, small for gestational age), environmental (e.g., air pollution, water pollution), and social determinants of health.10–13 A thorough evaluation of all potential causes of CKD is warranted.

Advance Care Planning

Encourage patients with CKD to consider advance care planning and their goals for future care, including for the end of life. Clinicians can find resources to help support difficult discussions, such as choosing not to start dialysis (conservative care pathway) or stopping dialysis treatments on the BC Renal Agency Palliative Care. Other resources for palliative care can also be found at the Provincial Advance Care Planning and the BC Guidelines on Palliative Care.

Methodology

This guideline is an updated version of the BC Guidelines: Chronic Kidney Disease guideline (2019). The recommendations are tailored to support primary care practice in BC and are based on recommendations from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. In situations where there is a lack of rigorous evidence, the experience informed clinical opinion is provided to support decision making and high-quality patient care. The guideline development process included engagement and consultation with primary care providers, specialists and key stakeholders.

Resources

Abbreviations

ACE-I

ACR

AKI

ARB

CGA

CKD

CVD

eGFR

GLP-1 RA

KDIGO

MRA

ns-MRA

NSAIDs

PCSK9i

SGLT2i

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio

Acute Kidney Injury

Angiotensin Receptor Blocker

Cause, eGFR, and Albuminuria (CKD classification)

Chronic Kidney Disease

Cardiovascular Disease

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist

Nonsteroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 Inhibitor

Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors

Practitioner Resources

- BC Renal: Clinical resources for physicians, dieticians, pharmacists and information for patients. See bcrenal.ca

- Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise (RACE): Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program allows Physicians (SPs and FPs), Medical Residents, Nurse Practitioners and Midwives to go to one online application or call one number and speak directly to specialists. See raceconnect.ca.

- Real Time Virtual Support (RTVS): Available to support practitioners in rural, remote, and First Nations communities in BC.

- Rural Urgent Doctor in aid (RUDi) for instant emergency medicine support.

- Child Health Advice in Real-Time Electronically (CHARLiE) for instant pediatric support.

- Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services (PLMS): Accountable for various functions related to the administration of lab services in B.C., and for implementing policies and processes on behalf of the Ministry of Health. To add a test to an existing order, change a test priority or to obtain a test result by phone, see PLMS Contact Us page, call 604-714-2800 or email plmsinfo@phsa.ca.

- PathwaysBC: An online resource that allows physicians, nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information. This includes specialists and specialty clinic wait times and areas of expertise. See: pathwaysbc.ca/login

- Health Data Coalition: An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist you in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing. HDC data can graphically represent patients in your practice with chronic diseases in a clear and simple fashion, allowing for reflection on practice and tracking improvements over time. See: Health Data Coalition – Better Information. Better Care. Better Patient Outcomes. (hdcbc.ca)

- Family Practice Services Committee

- Practice Support Program: Offers focused, accredited training sessions for BC physicians to help them improve practice efficiency and support enhanced patient care.

- Chronic Disease Management and Complex Care Incentives: Compensates family physicians for the time and skill needed to work with patients with complex conditions or specific chronic diseases.

- Relevant BC Guidelines

Patient, Family and Caregiver Resources

- HealthLinkBC: Patients can call HealthLinkBC at 8-1-1 toll-free in B.C., or for the deaf and the hard of hearing, call 7-1-1. They will be connected with an English-speaking health-service navigator, who can provide health and health-service information and connect them with a registered dietitian, exercise physiologist, nurse, or pharmacist. See: healthlinkbc.ca/

- BC Renal:

- Kidney Wellness Hub

- Advance Care Planning: Making Future Health Care Decisions. See www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/familysocial-supports/seniors/health-safety/advance-care-planning

Diagnostic Codes

585 - Chronic Renal Failure

Appendices

- Appendix A: Interpretation of Urine ACR Values to Assess Albuminuria and Proteinuria

- Appendix B: Recommended Drug Modifications in Presence of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)

- Appendix C: Medications for Chronic Kidney Disease

Associated Documents

The following document accompanies this guideline (available on the website):

References

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024 Apr;105(4S):S117–314.

- Writing Group for the CKD Prognosis Consortium. Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, Albuminuria, and Adverse Outcomes: An Individual-Participant Data Meta-Analysis. JAMA. 2023 Oct 3;330(13):1266–77.

- Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl. 2022 Mar 18;12(1):7.

- Bikbov B, Purcell CA, Levey AS, Smith M, Abdoli A, Abebe M, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2020 Feb 29;395(10225):709–33.

- BC Office of the Provincial Health Officer [data provider]. BC Observatory for Population and Public Health [publisher]. Chronic Disease Dashboard. Available at: http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/disease-system-statistics/chronic-disease-dashboard.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Treatment of End‐Stage Organ Failure in Canada, Canadian Organ Replacement Register, 2011 to 2020: End‐Stage Kidney Disease and Kidney Transplants — Data Tables. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2021., https://www.cihi.ca/en/organ‐replacement‐in‐canada‐corr‐annual‐statistics.

- Francis A, Harhay MN, Ong ACM, Tummalapalli SL, Ortiz A, Fogo AB, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024 Jul;20(7):473–85.

- Kelly JT, Palmer SC, Wai SN, Ruospo M, Carrero JJ, Campbell KL, et al. Healthy Dietary Patterns and Risk of Mortality and ESRD in CKD: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2017 Feb 7;12(2):272–9.

- Perkovic V, Tuttle KR, Rossing P, Mahaffey KW, Mann JFE, Bakris G, et al. Effects of Semaglutide on Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2024 Jul 10;391(2):109–21.

- Ferguson B, Doan V, Shoker A, Abdelrasoul A. A comprehensive exploration of chronic kidney disease and dialysis in Canada’s Indigenous population: from epidemiology to genetic influences. Int Urol Nephrol. 2024 Nov;56(11):3545–58.

- Komenda P, Lavallee B, Ferguson TW, Tangri N, Chartrand C, McLeod L, et al. The Prevalence of CKD in Rural Canadian Indigenous Peoples: Results From the First Nations Community Based Screening to Improve Kidney Health and Prevent Dialysis (FINISHED) Screen, Triage, and Treat Program. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2016 Oct;68(4):582–90.

- Kelly L, Matsumoto C lei, Schreiber Y, Gordon J, Willms H, Olivier C, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular comorbidities in adults in First Nations communities in northwest Ontario: a retrospective observational study. CMAJ Open. 2019 Jul;7(3):E568–72.

- Harasemiw O, Komenda P, Tangri N. Addressing Inequities in Kidney Care for Indigenous People in Canada. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. 2022 Aug;33(8):1474.

|

BC Guidelines are developed for the Medical Services Commission by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, a joint committee of Government and the Doctors of BC. BC Guidelines are adopted under the Medicare Protection Act and, where relevant, the Laboratory Services Act. Disclaimer: This guideline is based on best available scientific evidence and clinical expertise as of July 23, 2025. It is not intended as a substitute for the clinical or professional judgment of a health care practitioner. |