Diabetes Care

Effective Date: October 27, 2021

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Epidemiology

- Classification and Risk Factors

- Reducing the Risk of Developing Diabetes

- Screening and Diagnosis

- Management

- Resources

- Appendices

Scope

This guideline describes the care objectives for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of diabetes mellitus (diabetes or DM in this guideline) in adults aged ≥ 19 years. It focuses on the approaches and systems that are ideally in place to improve care for the majority of people, the majority of the time.

Diabetes in pregnancy (including gestational diabetes) is outside the scope of this guideline, although statements about pre-conception care for people with diabetes are included.

Key Recommendations

- Diabetes care should be holistic and centred around the person living with diabetes. Include an individualized management plan developed by the person with diabetes and their primary care provider(s).

- Goals include reducing microvascular and cardiovascular complication, reducing hyperglycemia and its symptoms, reducing risk and occurrence of hypoglycemia, and improving quality of life.

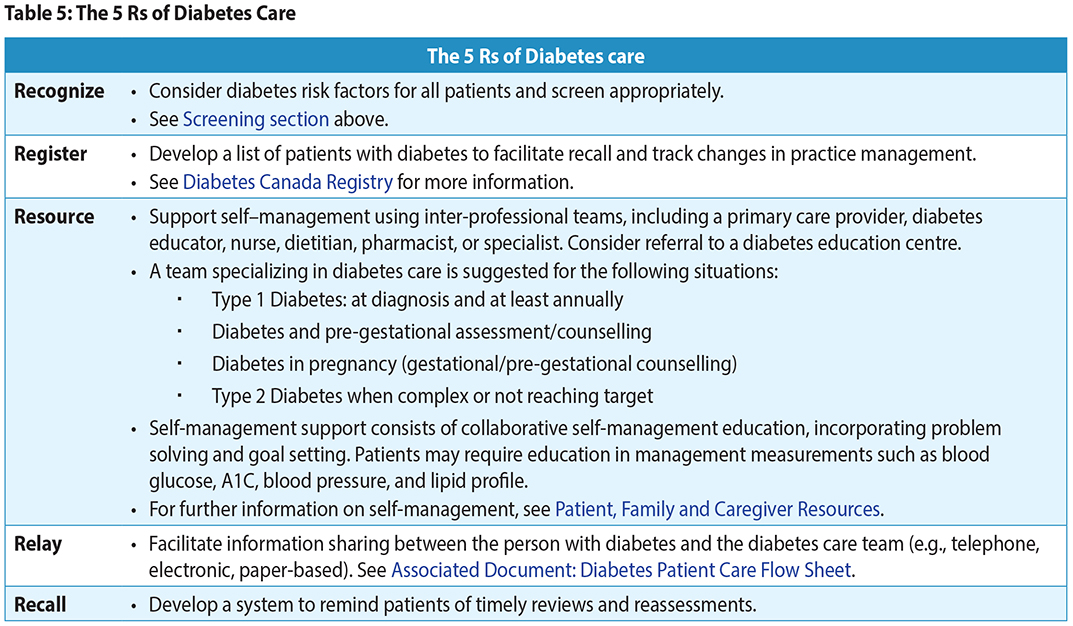

- The 5 Rs describe the key components to consider when organizing diabetes care in the office or clinic: Recognize, Register, Resource, Relay, and Recall.

- People ≥ 40 years of age and those younger than 40 with risk factors should be screened for diabetes.

- Glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C),fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or rarely 2-hour plasma glucose (2hPG) as part of a 75g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) can be used for diagnosis and screening.

- Individualized glycemic targets are based on age, duration of diabetes, risk of hypoglycemia, cardiovascular disease presence, and life expectancy.

- Measure A1C every 3 months to assess if glycemic goals are met. Consider testing every 6 months if targets are consistently met, and treatment and lifestyle are stable.

Management of Type 2 diabetes:

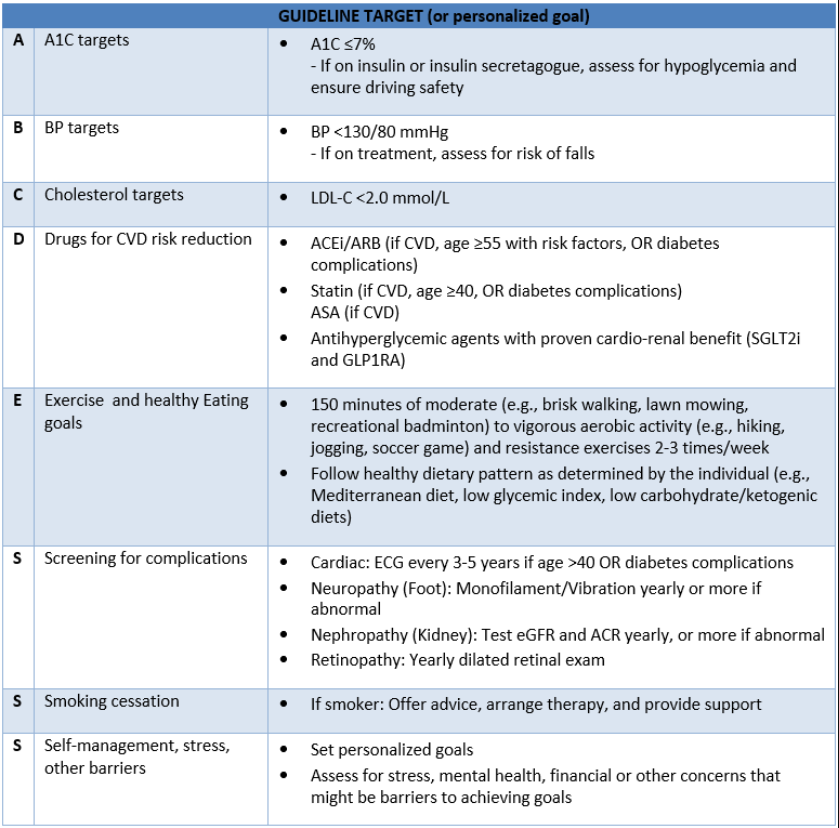

- A systematic approach to cardiovascular management is recommended, including healthy behaviour choices, glycemic and blood pressure control, and pharmacological interventions.

- Metformin is recommended as initial pharmacotherapy.

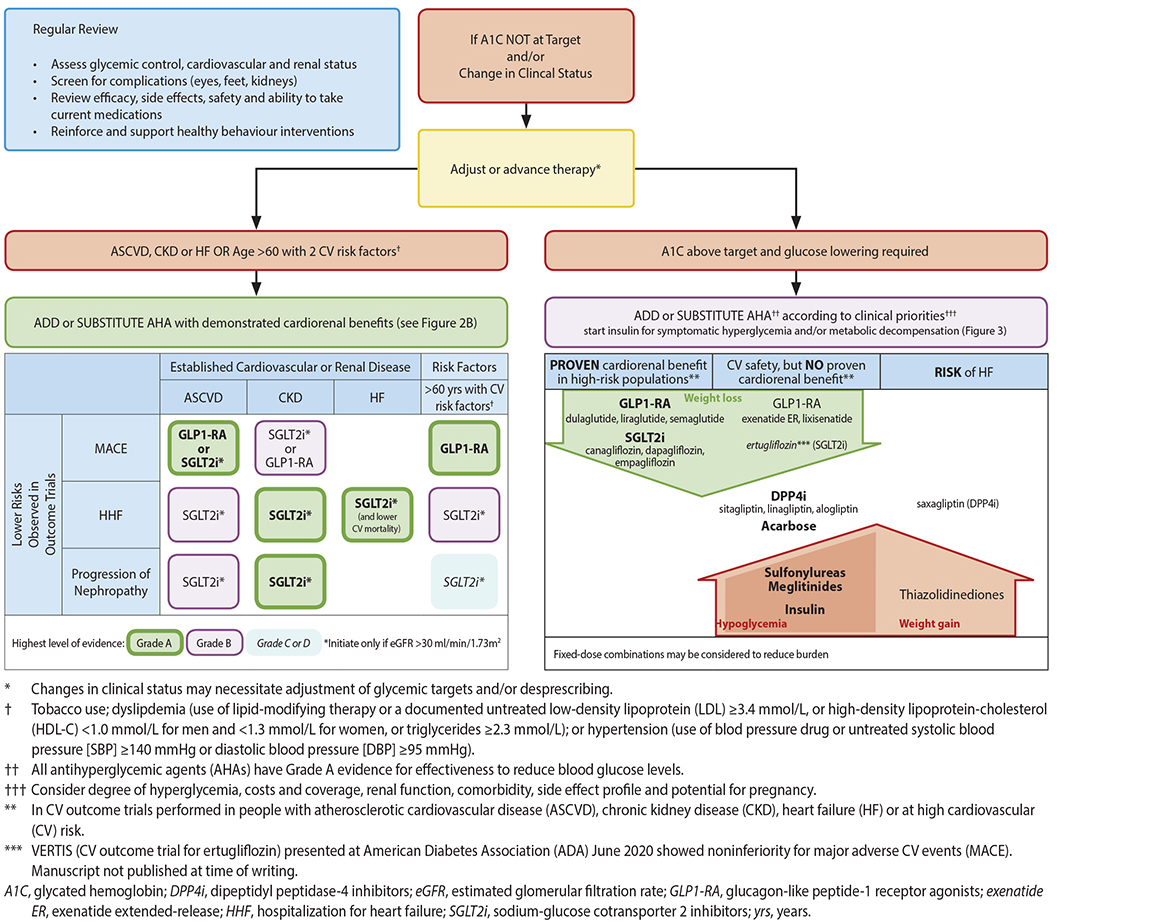

- NEW: Choose antihyperglycemic agents (AHA's) with cardiorenal protection for those with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD/CVS), Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), Heart Failure (HF) or ≥ age 60 with CVS risk factors. These agents should be used even if A1C is at target.

- Achieve glycemic goal (A1C target) in 3-6 months. Adjust therapy if glycemic targets are not reached or if there is a change in clinical status.

- If frailty, cognitive decline, or limited life expectancy are present, target an A1C of 7.1 to 8.5. Prioritize use of agents with low risk of hypoglycemia.

Epidemiology

- On average, over 32,000 people are diagnosed with diabetes every year in British Columbia (BC). In 2019/2020, over 497,000 people had diabetes in BC.1

- Geographic variations exist. Some regions have higher or lower rates of incidence and prevalence compared to the provincial totals.

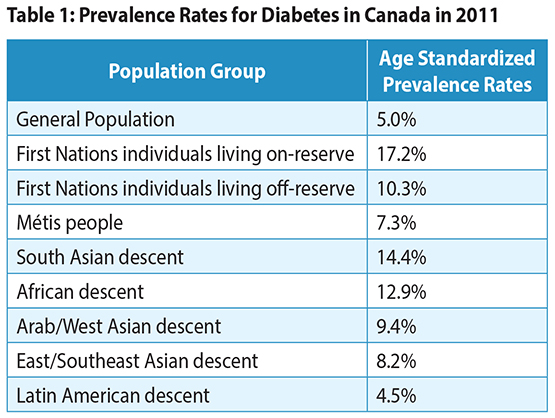

- In Canada, age standardized prevalence rates for diabetes for 2011 are shown in Table 1: Prevalence Rates for Diabetes in Canada 1, 2

Classification and Risk Factors

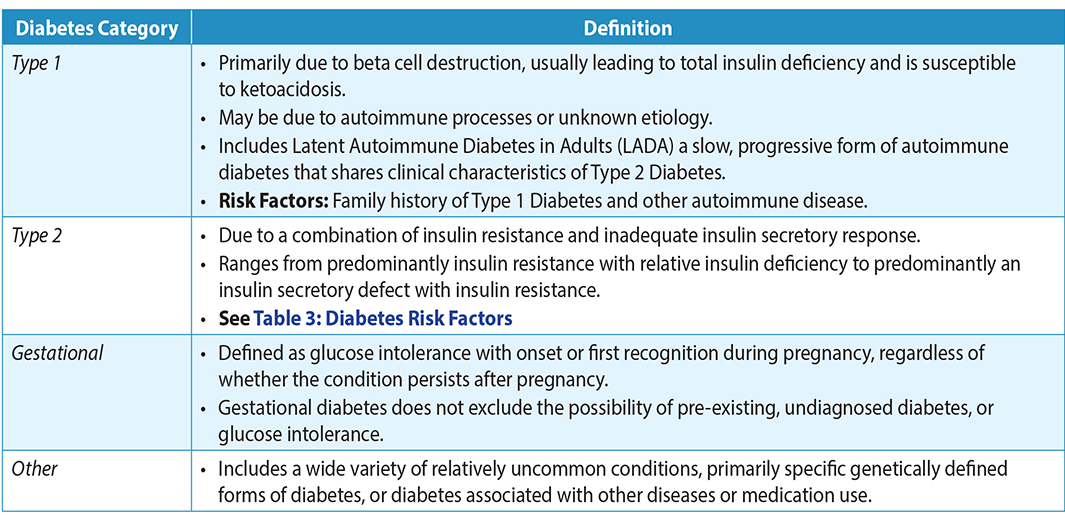

Diabetes mellitus is a complex chronic disease characterized by hyperglycemia due to defective insulin secretion, defective insulin action or both. 3, 4 See Table 2: Diabetes Classification, or Diabetes Canada’s Definition, Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes, Prediabetes and Metabolic Syndrome outline the different categories of diabetes.

Table 2: Diabetes Classification3, 4

[1] British Columbia Ministry of Health [data provider]. BC Observatory for Population and Public Health [publisher]. Chronic Disease Dashboard. Available at: http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/disease-system-statistics/chronic-disease-dashboard.

Reducing the Risk of Developing Diabetes

Type 1 Diabetes

Safe and effective therapies for the prevention of Type 1 Diabetes have not yet been identified.3

Type 2 Diabetes

For those with prediabetes and overweight/obesity, healthy behaviour changes (i.e., eating well and a minimum of 150 minutes of regular physical activity over 5 days a week) that result in a modest weight loss of 5% of initial body weight can delay or prevent Type 2 Diabetes from developing. In some cases, medication may help reduce the risk for developing diabetes.3,5 Pre-diabetes in geriatric populations may deserve an altered approach.6

Pharmacologic therapy with metformin can be considered for patients with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). When compared to standard diet and exercise metformin slightly reduces or delays development of diabetes. However, when compared to intensive diet and exercise, metformin does not provide an additional benefit in reducing or delaying development of diabetes.7 Diabetes Canada offers personalized prevention programs. See Canadian Diabetes Prevention Program for more information.

Diabetes Prevention in Ethnicities with High Risk: Certain ethnic groups, including Indigenous, South Asian, African, Arab, Asian, and Hispanic peoples are at very high risk for and have a high prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes (12% to 15% in the Western world).8,9 Activities aimed at reducing the risk for ethnic groups at higher risk for diabetes should consider the broader impact that the social determinants of health, colonialism and racism have on overall health. Consider cultural preferences and approaches that support self-determination.

Screening and Diagnosis

Screening3

- General screening for Type 1 Diabetes is not recommended.

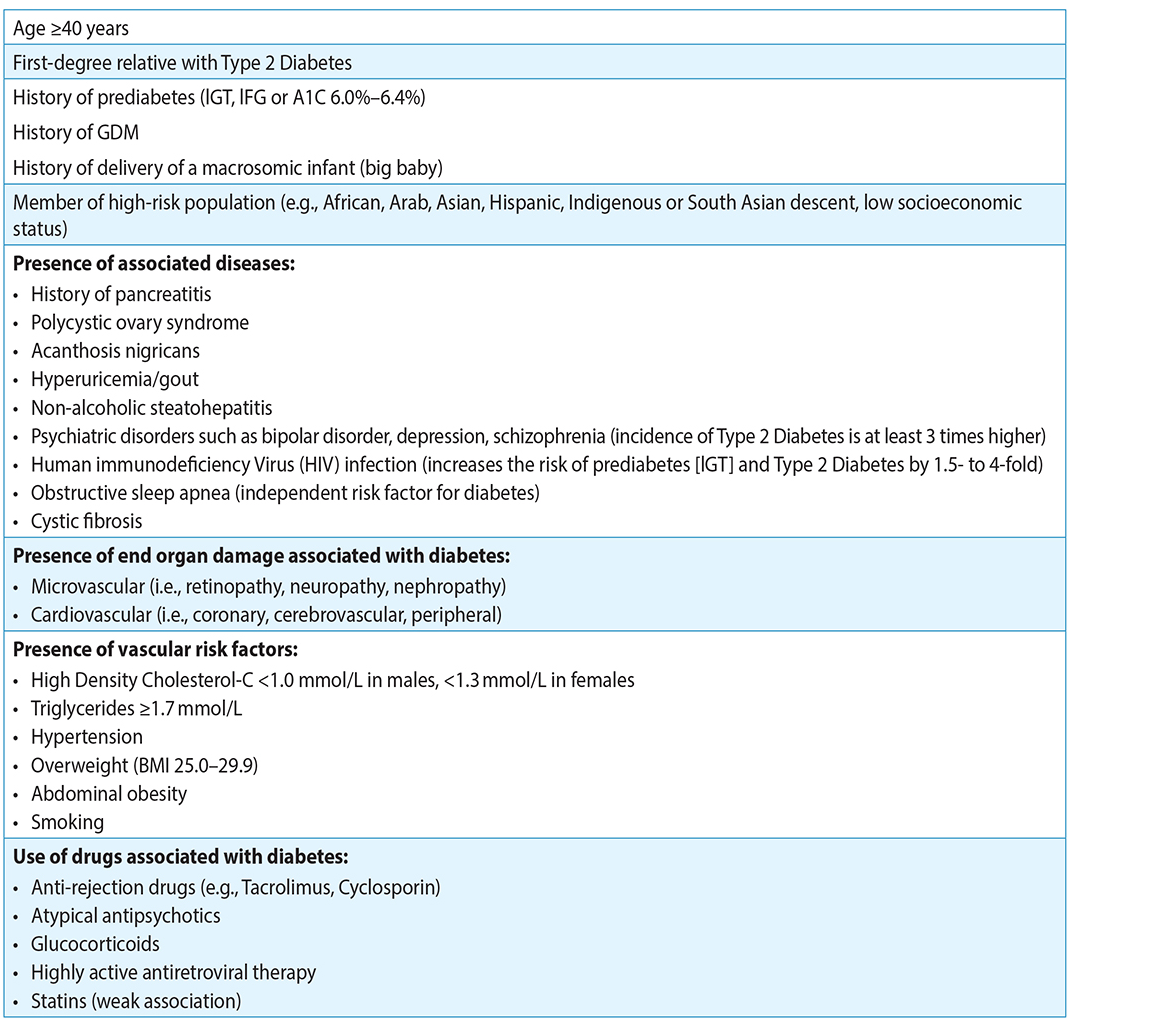

- Diabetes Canada recommends screening every 3 years in individuals ≥40 years of age or those at high risk in order to avoid missing those with undiagnosed dysglycemia, particularly in racial/ethnic minorities. Assess and screen more frequently in people with additional risk factors.3,10,11 See Appendix A Screening Algorithm for Type 2 DM in Adults (in 2021, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released updated recommendation for targeted screening for Type 2 Diabetes in overweight or obese adults aged 35 to 70 years 12).

- Canadian Diabetes Risk Assessment Questionnaire (CANRISK) is a statistically valid risk tool appropriate as an educational tool for patients to self-assess their risk.

Table 3: Diabetes Risk Factors3,4

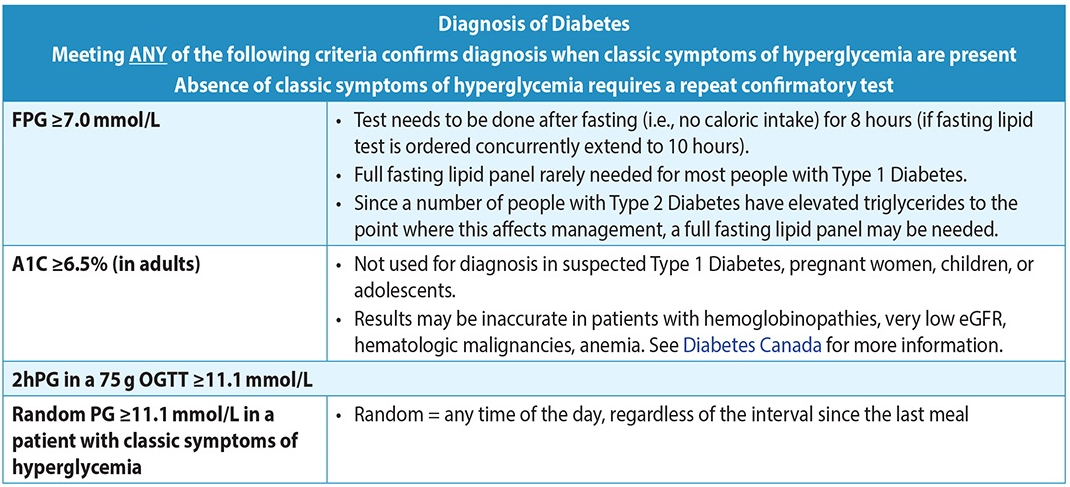

Diagnosis (Type 1 & 2)3

- Test with either A1C ($5.30*) and/or FPG ($1.46), or 2hPG ($12.94) in a 75g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Best choice of test will depend on clinical circumstances.2

Table 4: Diagnosis of Diabetes3

- In the absence of classic symptoms of hyperglycemia (e.g., polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, and/or unexplained weight loss), if a single lab test is in diabetes range, a repeat confirmatory test (preferably the same test) must be done another day (in a timely fashion) to rule out any error.

- In case of classic symptoms of hyperglycemia, a repeat test is not required. Diagnosis is confirmed.

- If there is a discordance between tests, repeat the previous positive test. See Diabetes Canada’s Screening for and Diagnosing Diabetes Healthcare Provider Tool.

- If the results of two different tests are both above diagnostic cut-points, the diagnosis is confirmed.

- In individuals who are suspected of Type 1 Diabetes, confirmatory testing should not delay treatment.

Management3

1. Organization of Care

Diabetes care is centred around the person living with diabetes. It includes an individualized management plan developed by the person with diabetes, their family/caregivers and primary care provider(s). The 5 R’s describe the key components for organizing diabetes care in the office or clinic. The Practice Support Program (PSP) Diabetes Learning Series includes additional information. BC physicians should contact their local PSP Regional Support Team coach for more information.

2. Individualized Targets

Blood Glucose: Glycemic Targets

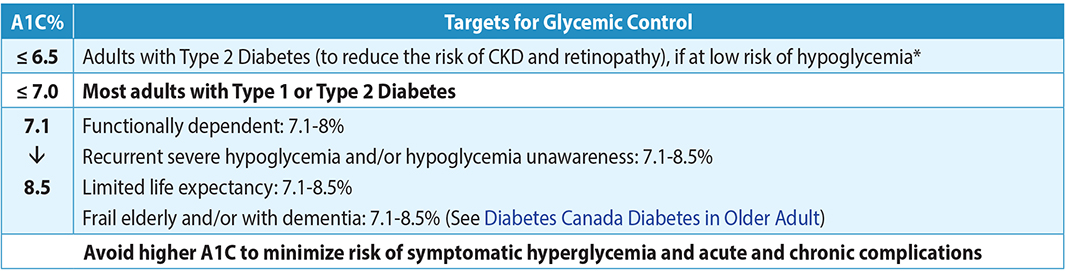

- The focus of glycemic goals is on achieving target A1C levels and on minimizing symptomatic hyper- and hypoglycemia. Glycemic targets are individualized based on the person’s age, duration of diabetes, risk of hypoglycemia, cardiovascular disease presence, and life expectancy. See Table 6: Targets for Glycemic Control for recommended targets, or to find a target for an individual patient, use the interactive Diabetes Canada tool for A1C targets.

Table 6: Recommandations for Glycemic Targets (adapted from Diabetes Canada)3

Note: At end of life, A1C measurement is not recommended. Avoid symptomatic hyperglycemia and any hypoglycemia.

Note: At end of life, A1C measurement is not recommended. Avoid symptomatic hyperglycemia and any hypoglycemia.

*based on class of antihyperglycemic medication(s) utilized and the person's characteristics.

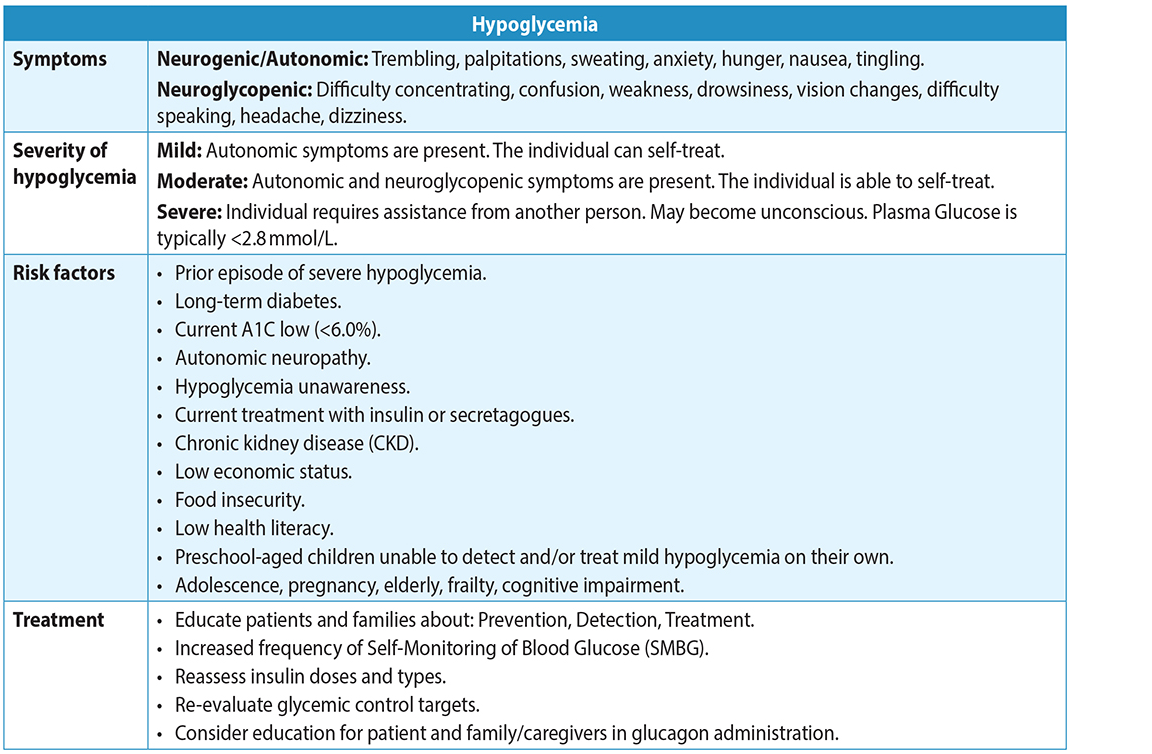

Blood Glucose: Hypoglycemia3

- Hypoglycemia can be a serious complication of therapy. Use less stringent glycemic targets in patients at risk of hypoglycemia. See Appendix B:Treatment of Hypoglycemia in Diabetes.

Table 7: Risk factors, Symptoms, Severity and Treatment of Hypoglycemia3

-

In BC, a driver with a medical condition (e.g., diabetes) that has the potential to affect their fitness to drive may be required to have a Driver’s Medical Examination Report completed by their primary care provider.13

- See the BC Driver Fitness Handbook for Medical Professionals for further information.

Blood Glucose: Long-Term Control3, 13

- Studies suggest there is a long-term benefit of glucose lowering early during Type 1 & 2 Diabetes, in terms of reducing complications.

- Measure A1C every 3 months to ensure that glycemic goals are being met and maintained.

- Consider testing A1C every 6 months if treatment and lifestyle remain stable and if targets have been consistently met. For individualizing the patient’s A1C targets use the interactive Diabetes Canada tool for A1C targets.

- Focus on minimizing symptomatic hypo- and hyperglycemia, in addition to A1C levels.

Blood Glucose: Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose3

- People with low risk of hypoglycemia may need less frequent Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose (SMBG) testing frequency. People at higher risk of hypoglycemia may need more frequent testing. SMBG is more important when using pharmacotherapies that can cause hypoglycemia.

- Develop a SMBG schedule with the patient and review records as needed. Frequency and timing of SMBG is individualized, based on type of diabetes, treatments (e.g., use of insulin), need for information, and individual’s capacity to use testing to modify behaviours or medications. Use Diabetes Canada’s SMBG frequency guidance tool.

- For most adults with Type 2 Diabetes using antihyperglycemic agents (without insulin) or healthy behavior interventions only to meet glycemic targets, the value of routine use of SMBG is significant only in the short term.14,15

- Annual accuracy verification of glucose meter is recommended (simultaneous fasting glucose meter/lab comparison within 20%).

- Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and Flash glucose monitoring (FGM) systems measure glucose concentrations in the interstitial fluid. CGM and FGM can provide real time notifications when glucose level is above or below a preset limit or capture glucose readings for retrospective analysis. CGM sensors can be worn continuously for 7 to 10 days, and FGM sensors can be worn continuously for up to 14 days. FGM displays blood glucose levels when the sensor is “flashed” with a reader device on demand. For the latest PharmaCare coverage of glucose monitoring devices, please refer to PharmaCare Medical Supplies Coverage.

- Increasing evidence suggest that decreasing the glucose variability may decrease vascular complications of diabetes.

- Blood glucose test strips are a Pharmacare benefit for those holding a valid Certificate of Training in SMBG from a BC diabetes education centre. See Appendix C: PharmaCare quantity limits for blood glucose test strips and information on coverage.

3. Non-Pharmacological Management

Healthy Behaviour Interventions and Holistic Health Approaches

- People with diabetes will benefit from healthy behaviour education and interventions, including

- Activity 150 minutes per week etc.

- Nutrition therapy3 (individualized nutrition counselling)

- Sustained weight loss >5% if have obesity, etc.

- Smoking cessation

- Regular physical activity (i.e., at least 150 minutes per week of aerobic exercise and two sessions of resistance training per week, if not contraindicated), sustained weight loss of ≥5% of initial body weight for individuals with obesity, and smoking cessation.

- Stress management, sleep, and mental and emotional wellness are important aspects of overall diabetes care and management.

- Diabetes education clinics are offered throughout the province. People may also find value in other approaches that are more specific to their community and culture.

3 Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT) is an evidence-based approach used in the nutrition care process (NCP) of treating and/or managing chronic diseases. MNT is often used in clinical and community settings, that focuses on nutrition assessment, diagnostics, therapy, and counselling. MNT is often implemented and monitored by a registered dietitian, in collaboration with physicians and other health professionals.

Weight Management

- Sustained weight loss of ≥5% of initial body weight can improve glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors. For people with diabetes who are overweight/obese, weight loss and A1C lowering may be possible with healthy behaviour modifications including nutrition therapy, increased and regular physical activity, and stress management.

- When discussing weight and health with patients, it is recommended that health care practitioners use approaches presented in the 2020 Obesity Canada guidelines.

- The root causes of obesity (e.g., trauma, chronic stress, food insecurity, medical conditions, genetics, social determinants of health, etc.) should be considered as conventional treatment options may not be feasible for all people.16

- People with diabetes may choose to try to lose weight by changing their diet. They should consult with their health-care provider to define goals and reduce the likelihood of adverse effects. They may need more frequent blood glucose monitoring and adjustment of medications that may cause hypoglycemia (e.g., if pursuing low carbohydrate diets, intermittent fasting, very low carbohydrate/keto diet).17 Ongoing care from a Registered Dietitian is also beneficial.

- Pharmacotherapy directed at weight management has not been adequately studied in people with Type 1 Diabetes.

- For persons living with Type 2 Diabetes and a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2, pharmacotherapy (liraglutide 3.0 mg, naltrexone/bupropion combination, and orlistat) can be used in conjunction with health behaviour changes for weight loss and improvement in glycemic control.16

- For persons with prediabetes and BMI > 27kg/m2, who have or Type 2 Diabetes may benefit from pharmacotherapy (liraglutide 3.0 mg, orlistat, semaglutide) may be considered in conjunction with health behaviour changes to delay or prevent Type 2 Diabetes.16

- Consider diabetes medications with favourable weight loss profiles (SGLT2i and GLP1 receptor agonists).

- Bariatric surgery is a therapeutic option for people with Type 2 Diabetes and body mass index ≥35.0 kg/m2 who have already attempted healthy behaviour choices with or without weight management medication(s).

- Some procedures are covered by the Medical Services Plan.

- For more information on obesity management, see BCGuidelines.ca – Overweight and Obese Adults: Diagnosis and Management, Diabetes Canada: Weight Management in Diabetes and Obesity Canada: Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines

4. Individualized Pharmacologic Management

Type 1 Diabetes

Multiple (3-4) daily insulin injections or the use of Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII or insulin pump) should be considered as part of an intensive diabetes management program. PharmaCare covers insulin pumps for people with Type 1 diabetes or other forms of diabetes requiring insulin. PharmaCare covers supplies for insulin pumps, regardless of whether the pump was covered. For more information visit PharmaCare for B.C. residents: Medical Devices and Supplies Coverage.

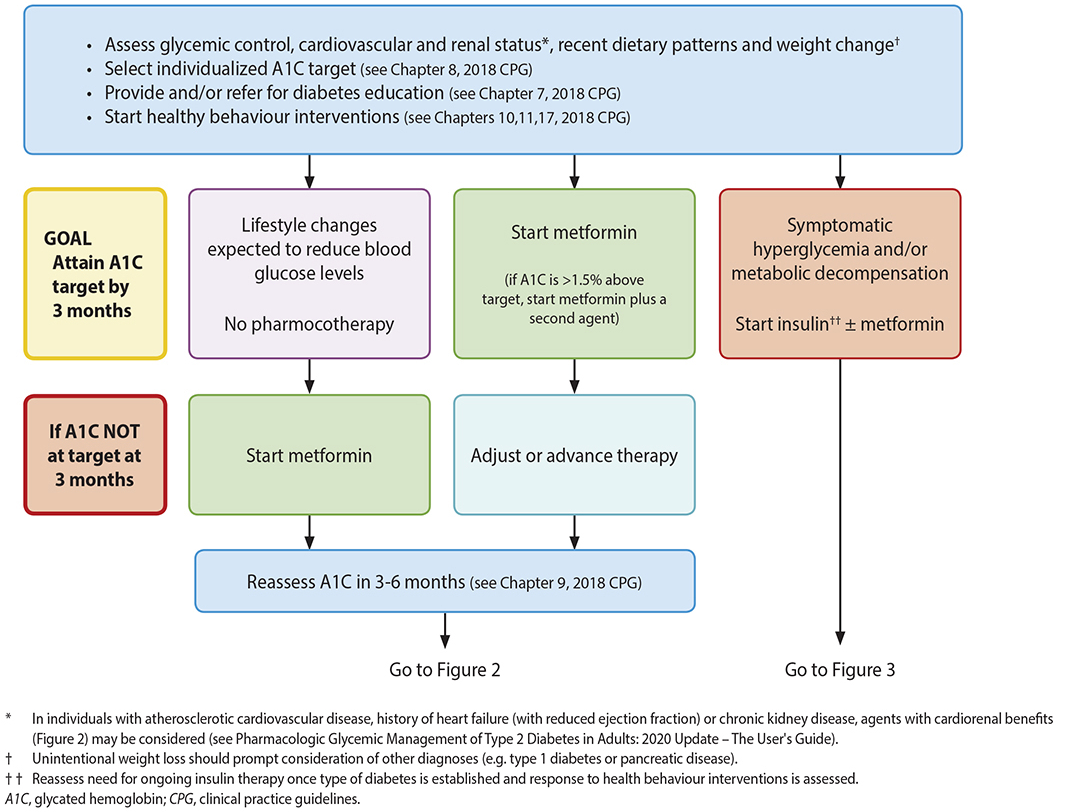

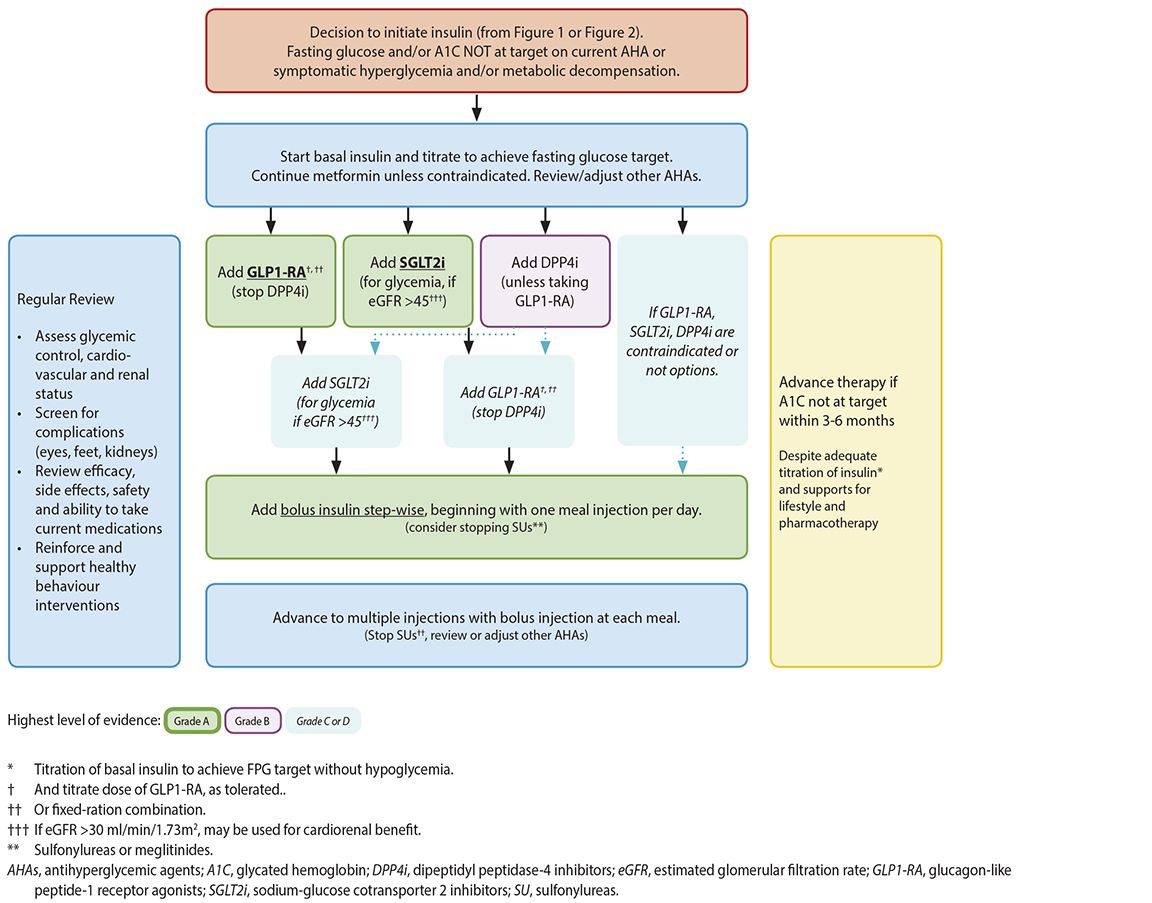

The following algorithms (Figures 1-3) from Diabetes Canada’s Pharmacologic Glycemic Management of Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: 2020 Update18 (used here with permission) lay out the management pathway for Type 2 Diabetes.

- If glycemic targets are not achieved with existing antihyperglycemic medication(s), or the individual’s clinical status changes, other classes of agents should be used (either by addition or replacement) to reduce cardiorenal impact and/or improve glycemic control; or glycemic targets should be reassessed. See: Appendix D: Antihyperglycemic Agents and Adjunctive Agents for Use in Type 2 Diabetes.

- Consider the following medications in adults with:

|

Diabetes AND |

Medication |

|

Atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) |

GLP1-RA or SGLT2i |

|

History of HF (reduced ejection fraction ≤ 40%) |

SGLT2i and avoid TZD and saxagliptin |

|

CKD and an estimated eGFR >30 mL/min/1.73m2 |

SGLT2i |

|

Aged 60 years or older with at least 2 CV risk factors |

GLP1-RA, SGLT2i |

- If reducing risk of hypoglycemia is a priority, consider DPP4i or GLP1-RA, SGLT2i, as add-on medication.

- If weight loss is a priority, consider GLP1-RA and/or SGLT2i as add-on medication.

- When glycemic targets are not achieved, consider addition of a basal insulin regimen. Bolus insulin may be initiated using a stepwise approach. See Figure 3: Starting or advancing insulin in Type 2 Diabetes. To minimize the risk of hypoglycemia, consider a long-acting insulin analogue (insulin glargine U-100, glargine U-300, detemir, degludec) over NPH insulin. Insulin degludec or insulin glargine U-300 (57) may be considered over insulin glargine U-100 for individuals with > 1 risk factor for hypoglycemia. See: Appendix E: Insulin: Therapeutic Considerations and Availability.

- If glycemic targets are not achieved with insulin, consider GLP1-RA or SGLT2i or DPP4i as add-on therapy. When bolus insulin is added, consider rapid-acting analogues over short acting (regular) insulin. Bolus insulin may be initiated using a stepwise approach.

Figure 1: Management of Type 2 Diabetes3

Figure 2: Reviewing, Adjusting or Advancing therapy in Type 2 Diabetes3

Figure 3: Starting or Advancing Insulin in Type 2 Diabetes3

5. Preventing complications and comorbidities

Global Cardiovascular Management3

- People with diabetes are at significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease. BCGuideline.ca: Cardiovascular Disease: Primary Prevention recommends using a risk assessment tool, medical history, physical examination, and lipid profile. While the current Framingham Risk Score now includes diabetes status to individualize a Type 2 Diabetes patient’s risk, the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes (UKPDS) risk calculator is the recommended tool.

- A risk assessment calculator is not recommended for people with Type 1 Diabetes.

- A systematic approach to vascular protection is recommended, including healthy behaviour interventions, glycemic control, blood pressure control, and pharmacological interventions.

- Consider the “ABCDESSS” as a useful mnemonic device for vascular protection strategies. See Table 8: Consider the ABCDESSS below.

Table 8: Consider the ABCDESSS

Heart Failure3

- ·The incidence of heart failure is 2 to 4 times higher in people with diabetes compared to those without and, when present, occurs at an earlier age. It is recognized that diabetes can cause heart failure independently of ischemic heart disease by causing a diabetes-related cardiomyopathy.

- SGLT2i reduce the risk of hospitalization for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.20 Individuals with diabetes and heart failure should receive the same heart failure therapy. See BCGuidelines: Chronic Heart Failure - Diagnosis and Management.

Hypertension3

- Blood pressure control is a priority for people with diabetes. Record at diagnosis and regularly thereafter.

- For people with diabetes, reaching a desirable Manual Office Blood Pressure (MOBP) reading of <130/80 is recommended by Hypertension Canada, American College of Cardiology, European Society of Hypertension and the Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines. The desired level of MOBP <130/80 was determined by these groups following review of several recent clinical trials that support lower Blood Pressure levels with reductions in risk of microvascular diabetic endpoints, stroke and major cardiovascular events.21,22 See BCGuidelines: Hypertension - Diagnosis and Management.

- If healthy behavior interventions are insufficient, then pharmacological treatment may be required:

- DM with moderately or severely increased albuminuria, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, or cardiovascular disease risk factors:

- First-line – ACEi or ARB (if ACEi intolerant).

- Second-line – Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (DHP-CCB) (e.g., amlodipine, felodipine, and nifedipine).

- DM no chronic kidney disease or cardiovascular disease risk factors:

- First-line – ACEi or ARB or Thiazide/Thiazide-like diuretic or DHP-CCB. ACEi and ARBs should not be used in combination.

- Second-line – Combination of first line drugs (note: in combination with ACEi, a DHP-CCB is preferable to a thiazide/thiazide-like diuretic.

- DM with moderately or severely increased albuminuria, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, or cardiovascular disease risk factors:

Lipid Lowering Strategies3

- Primary prevention: healthy behavior interventions are usual first-line strategies in vascular protection. Statin therapy is a second line intervention, considered on an individual basis following an evaluation of risk and benefits. Additional agents now approved are ezetimbe, PSK-9i and IPE.

- Risk assessment discussions on whom to use statin therapy are discussed in the 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia.23

- Diabetes Canada aligns with the 2016 CCS guidelines and recommends statin therapy to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in adults with Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes with any of the following features:

- Age ≥ 40 years.

- Age > 30 years and diabetes duration > 15 years.

- Microvascular complications.

- Cardiovascular disease.

- The CCS 2021 guidelines recommends treating high risk and intermediate risk people (listed above) to a specific LDL-C target of ≤ 1.8 mmol/L. Alternate targets include an apoB target of ≤0.7 g/L and a non-HDL-C target of ≤2.4 mmol/L. The recommendation for low-risk people is to treat to 50% of their baseline LDL-C. See Associated Document: Patient Care Flowsheet for frequency of monitoring.

- In people with diabetes achieving LDL-C goal with statin therapy; fibrates, niacin and omega-3 fatty acids should not be routinely added for the sole purpose of further reducing CV risk.

- If statin therapy is decided upon, select statin based on tolerability, potential for drug interactions, and cost. For information on dosages, see BCGuidelines.ca: Cardiovascular Disease - Primary Prevention.

Retinopathy3

- Early recognition and treatment of retinopathy can prevent vision loss.

- Retinopathy can worsen during pregnancy. Women with existing diabetes considering pregnancy or in early pregnancy should be assessed by an eye care specialist.

- Those with pre-existing eye disease who have a rapid significant drop in A1C can experience a worsening in retinopathy. Closer follow-up with an eye care specialist is recommended.

- Ensure individual with Type 2 Diabetes receives dilated pupil retinal examination at diagnosis, then every 1-2 years or as indicated. For individuals with Type 1 Diabetes the first pupil retinal exam can start at 5 years post-diagnosis, then annually.

- Optimal glycemic control and BP levels reduces the onset and progression of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy.

- Anti-VEGF injections, laser therapy and/or vitrectomy may be used to manage diabetic retinopathy.

Nephropathy and Chronic Kidney Disease3

- People with Type 1 Diabetes are not expected to have kidney disease at the time of onset of diabetes, so screening can be delayed until the duration of diabetes exceeds 5 years post-pubertal and repeated annually.

- Significant renal disease can be present at the time of diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes, so screening should be initiated immediately at the time of diagnosis and then repeated annually.

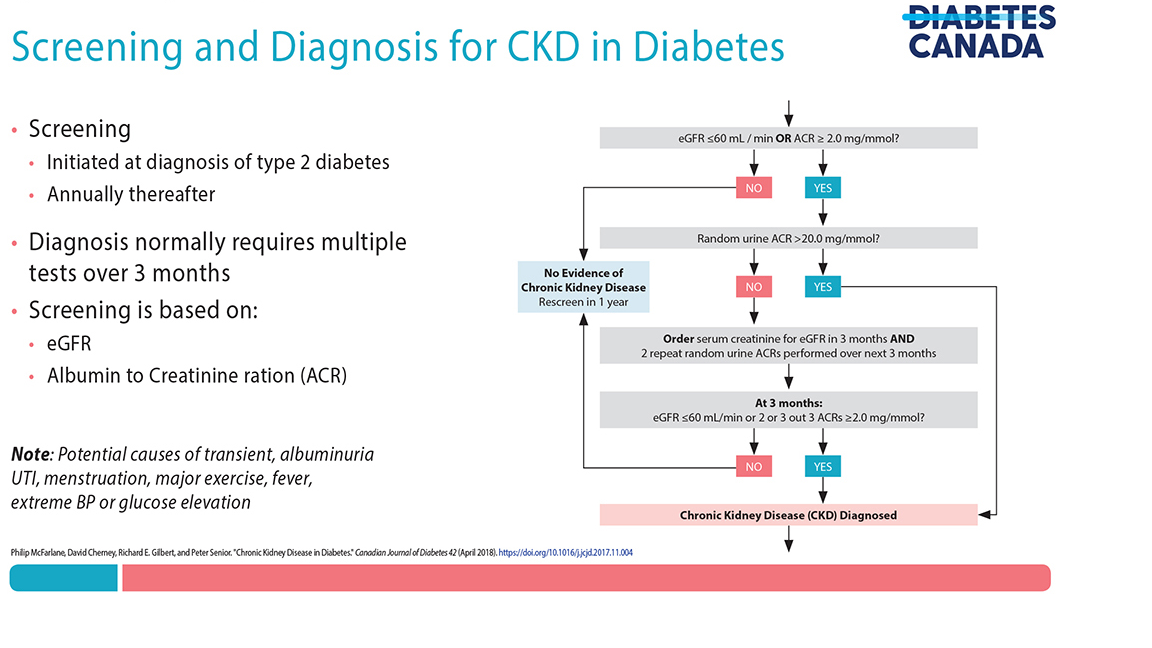

- A diagnosis of CKD should be made in people with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or random urine albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥2.0 mg/mmol on at least 2 of 3 samples over a 3-month period. See Figure 4: Screening and Diagnosis for CKD in Diabetes below (adapted from Diabetes Canada).

Figure 4: Screening and Diagnosis for CKD in Diabetes

- Check ACR, eGFR, and urinalysis annually: if tests are normal continue annual monitoring. If tests are abnormal, repeat within 3 months in a well hydrated state to confirm, unless there is deteriorating renal function requiring urgent investigation, management and referral.

- If abnormal and confirmed, monitor renal function (ACR, eGFR) more frequently. Elevated ACR can be an early marker of diabetes nephropathy. See BCGuidelines: Chronic Kidney Disease - Identification, Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients.

- Optimize blood pressure and glucose control to prevent or slow progression of nephropathy.

- Progression of chronic kidney disease in diabetes can also be slowed using medications that disrupt the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (ACE-I, ARBs RAAS) and SGLT-2i.

- The Kidney Risk Calculator may be used to calculate the 2 and 5 year probability of kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplant based on age, gender, eGFR and ACR.

Neuropathy3

- In people with Type 2 Diabetes, screening for peripheral neuropathy should begin at diagnosis of diabetes and occur annually thereafter.

- In people with Type 1 Diabetes, annual screening should commence after 5 years post-pubertal duration of diabetes.

- The best way to prevent diabetic neuropathy is to achieve long-term glycemic control.1

- Screening can be performed via 10-g monofilament or 128-Hz tuning fork during foot exam.

- At a minimum, check annually for symptoms or findings such as peripheral anesthesic neuropathy or pain, or autonomic neuropathy (e.g., erectile dysfunction, gastrointestinal disturbance, orthostatic hypotension).

Foot Examination3

- Examine feet annually, or more frequently for those at high risk (e.g., known neuropathy, macrovascular complications, smokers, patient with foot or leg abnormalities).

- Management of foot ulcer requires an interdisciplinary care approach to address infections, wound care, glycemic control, lower-extremity vascular status, and off-loading of high pressure areas.

- Encourage regular self-examination of feet. A foot care checklist is available here: Diabetes.ca/footcare.

Psychosocial Aspects of Diabetes3

- Psychosocial factors affect many aspects of diabetes management and glycemic control.

- Screen for psychiatric disorders including depression, anxiety and eating disorders. Consider using screening tools such as Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), or GAD-7. Treatment of these conditions may improve outcomes. Additional life factors such as adverse childhood experiences, trauma, and stress should also be addressed.

- Disease specific psychologic issues include diabetes-related distress (i.e., the emotional impact of living with diabetes, stressors around self-management regimen, the stress associated with social relationships and including the patient-provider relationship), fear of hypo- and hyperglycemia, and fear around insulin use.

- Use person-centred approaches such as motivational interviewing, and cognitive behavioral therapy to help reduce stress, cope with diabetes diagnosis and achieve self-management.

Sexual Dysfunction

- Diabetes can significantly impair sexual function in both males and females. This is multifactorial including microvascular, neuropathy, and hormonal.24 This can lead to significant psychosocial impact and should be reviewed with patients routinely.

Immunizations3

- Annual influenza vaccination is recommended.

- In adults with DM, pneumococcal vaccination/pneumo-vax 23 is recommended. Re-vaccination is recommended for those ≥ 65 years of age and if the original vaccine was given when they were < 65 years of age. For further information, see the BC Centre for Disease Control Immunization Manual.

In Case of Acute Illness3

- Educate those with diabetes about acute illness particularly when they are unable to drink enough fluid to keep hydrated or when vomiting.

- People who experience illness and are unable to maintain adequate fluid intake, or at risk for acute decline in renal function (e.g., gastrointestinal upset or dehydration) should increase the frequency of SMBG and may need to adjust doses of insulin, adjust or hold antihyperglycemic agents and/or other medications. A mnemonic for these medications is: SADMANS (Sulfonylureas, ACEi, Diuretics, Direct renin inhibitors, Metformin, ARB, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory, SGLT2 inhibitors). See the Sick Day medication list at: Diabetes.ca/sick-day/medication/list and Diabetes Canada Sick Day Management Tool.

- Encourage individuals with Type 1 Diabetes to perform ketone testing during acute illness accompanied by elevated blood glucose. Blood ketone testing may be preferred over urine ketone testing.

6. Populations with Additional Considerations

Populations with Mental Health Concerns

- People diagnosed with serious mental illnesses (e.g., major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia), or those taking antipsychotic medications, have a higher risk of developing diabetes and worse outcomes compared to the general population and require regular metabolic monitoring.

- Liaise with mental health-care professionals as necessary to ensure appropriate care plans are developed that include psychosocial interventions and glycemic control.

- Mental health treatments may improve diabetes outcomes.

Indigenous People

- The causes of higher rates of diabetes among Indigenous people in Canada are complex. Clinicians should seek to understand the relationship between the history of colonization and diabetes (See Diabetes Canada Chapter Type 2 Diabetes and Indigenous Peoples), including the historic and ongoing impacts of trauma, loss of culture, food insecurity, and systemic racism, including healthcare settings.

- The recently released provincial report titled In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous –specific Racism and Discrimination in BC Health Care highlighted findings of significant experiences of racism by Indigenous people in the BC health care system. All clinicians have a role to play in breaking the cycle of racism and discrimination towards Indigenous clients. It is recommended that all clinicians read the In Plain Sight Full Report and/or Summary Report and consider what changes they might make in their own practices.

- Create a culturally safe space by asking Indigenous clients about the importance of culture, family and community in their treatment care plans, and inquiring about their use of any traditional medicines.

Geriatric Population

- Older adults with diabetes, who are functionally fit and have a life expectancy of greater than 10 years, receive the same treatment as younger adults in order to achieve the same glycemic, BP and lipid targets. For more information about diabetes in older people, see Diabetes Canada: Diabetes in Older People.

In frail elderly people with diabetes:

- Pay attention to:

- Polypharmacy – review full medication list periodically. A patient presenting with depression, falls, cognitive impairment, perceptual difficulties, or urinary incontinence should trigger a full medication review.

- Glycemic targets - consider less strict targets (7.1-8.5% A1C) in those with limited life expectancy, high functional dependency, extensive disease, or multiple co-morbidities.

- Postural hypotension - contributes to falls and fractures. Check lying and standing BP; review medications

- Renal function - regularly review medications to reduce or eliminate nephrotoxic effects and prevent hypoglycemic events.

- Consider use of:

- DPP-4 inhibitors over sulfonylureas. Use sulfonylureas (especially glyburide) with caution as the risk of hypoglycemia increases with age.

- Lower starting doses (initial doses can be half of those for younger people) and slower titration of medications.

- Long-acting basal analogues (lower frequency of hypoglycemia), rather than intermediate-acting or premixed insulin.

- Cognitive assessment (such as clock face tests), and functional dexterity verification prior to initiating insulin. See the BCGuidelines.ca: Cognitive Impairment - Recognition, Diagnosis and Management in Primary Care for assessment tests.

- Premixed insulins and prefilled insulin pens preferred to reduce dosing errors and to potentially improve glycemic control.

- In those with clinical CVD and in whom glycemic targets are not achieved with existing antihyperglycemic medication(s) and with an eGFR >30 mL/min/1.73 m2, an antihyperglycemic agent with demonstrated CV outcome benefit could be added to reduce the risk of major CV events.

Pregnancy

- Contraception and pre-pregnancy planning in all patients with diabetes is critical to improved outcomes. Refer promptly for specialized care.

- Optimal glucose control pre-conception (A1C≤ 7% or ≤6.5% if safely achieved) will reduce risk of:

- spontaneous abortion

- congenital abnormalities

- preeclampsia

- progression of retinopathy

- Statins and ACEi are not safe in pregnancy and should be discontinued.

- ACE/ARBs for hypertension should be discontinued prior to pregnancy and once pregnant if using for CKD.

- Statins and/or fibrates should be discontinued prior to pregnancy.

- Metformin and glyburide pre-conception may be continued if glycemic control is adequate until pregnancy is achieved. Those on other medications should be transferred to insulin prior to pregnancy or in early pregnancy while awaiting specialty care.

- Identify women with previous gestational diabetes. They can develop Type 2 Diabetes and special attention is necessary prior to future pregnancies and in later life.

- See the Diabetes Canada guide on women of child-bearing age at: Guidelines.diabetes.ca/cpg/chapter36.

- Contraception and pre-pregnancy planning in all patients with diabetes is critical to improved outcomes. Refer promptly for specialized care.

- Optimal glucose control pre-conception (A1C≤ 7% or ≤6.5% if safely achieved) will reduce risk of:

- spontaneous abortion

- congenital abnormalities

- preeclampsia

- progression of retinopathy

- Statins and ACEi are not safe in pregnancy and should be discontinued.

- ACE/ARBs for hypertension should be discontinued prior to pregnancy and once pregnant if using for CKD.

- Statins and/or fibrates should be discontinued prior to pregnancy.

- Metformin and glyburide pre-conception may be continued if glycemic control is adequate until pregnancy is achieved. Those on other medications should be transferred to insulin prior to pregnancy or in early pregnancy while awaiting specialty care.

- Identify women with previous gestational diabetes. They can develop Type 2 Diabetes and special attention is necessary prior to future pregnancies and in later life.

- See the Diabetes Canada guide on women of child-bearing age at: Guidelines.diabetes.ca/cpg/chapter36.

References

- Ghanem S. Diabetes in Canada: Backgrounder. Ottawa: Diabetes Canada; 2020. :8.

- Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Data Tool, 2017 Edition. A joint initiative of the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, Statistics Canada and the Canadian Institute of Health Information. [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 23]. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/health-inequalities/data-tool/Index?Cat=17&Ind=370&Lif=17&MS=6

- Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Diabetes Canada 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(Suppl 1):S1-S325. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 16]. Available from: http://guidelines.diabetes.ca/cpg

- Association AD. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020 Jan 1;43(Supplement 1):S14–31.

- Group DPPR. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin [Internet]. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012512. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2009 [cited 2020 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa012512

- Rooney MR, Rawlings AM, Pankow JS, Echouffo Tcheugui JB, Coresh J, Sharrett AR, et al. Risk of Progression to Diabetes Among Older Adults With Prediabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Apr 1;181(4):511–9.

- Madsen KS, Chi Y, Metzendorf M-I, Richter B, Hemmingsen B. Metformin for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in persons at increased risk for the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Nov 17];(12). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008558.pub2/full

- Chowdhury TA, Grace C, Kopelman PG. Preventing diabetes in south Asians. BMJ. 2003 Nov 8;327(7423):1059–60.

- Egede LE, Dagogo-Jack S. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: focus on ethnic minorities. Med Clin North Am. 2005 Sep;89(5):949–75, viii.

- O’Brien MJ, Lee JY, Carnethon MR, Ackermann RT, Vargas MC, Hamilton A, et al. Detecting Dysglycemia Using the 2015 United States Preventive Services Task Force Screening Criteria: A Cohort Analysis of Community Health Center Patients. PLOS Med. 2016 Jul 12;13(7):e1002074.

- Siu AL, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force*. Screening for Abnormal Blood Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Dec 1;163(11):861–8.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021 Aug 24;326(8):736–43.

- Laiteerapong N, Ham SA, Gao Y, Moffet HH, Liu JY, Huang ES, et al. The Legacy Effect in Type 2 Diabetes: Impact of Early Glycemic Control on Future Complications (The Diabetes & Aging Study). Diabetes Care. 2019 Mar 1;42(3):416–26.

- Malanda UL, Welschen LM, Riphagen II, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Bot SD. Self‐monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2020 Oct 21];(1). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005060.pub3/full

- Zhu H, Zhu Y, Leung S. Is self-monitoring of blood glucose effective in improving glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes without insulin treatment: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016 Sep 1;6(9):e010524.

- Wharton S, Lau DCW, Vallis M, Sharma AM, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Can Med Assoc J. 2020 Aug 4;192(31):E875.

- Diabetes Canada Position Statement on Low-Carbohydrate Diets for Adults With Diabetes: A Rapid Review - ScienceDirect [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.hlth.gov.bc.ca/science/article/abs/pii/S1499267120300976?via%3Dihub

- Lipscombe L, Butalia S, Dasgupta K, Bsp DTE, BScPhm LM, Shah BR, et al. Pharmacologic Glycemic Management of Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: 2020 Update. Can J Diabetes. 2020;17.

- Tsapas A, Avgerinos I, Karagiannis T, Malandris K, Manolopoulos A, Andreadis P, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Glucose-Lowering Drugs for Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Aug 18;173(4):278–86.

- Ezekowitz JA, O’Meara E, McDonald MA, Abrams H, Chan M, Ducharme A, et al. 2017 Comprehensive Update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure. Can J Cardiol. 2017 Nov;33(11):1342–433.

- Tobe SW, Gilbert RE, Jones C, Leiter LA, Prebtani APH, Woo V. Treatment of Hypertension. Can J Diabetes. 2018 Apr;42:S186–9.

- Reboussin David M., Allen Norrina B., Griswold Michael E., Guallar Eliseo, Hong Yuling, Lackland Daniel T., et al. Systematic Review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018 Jun 1;71(6):e116–35.

- Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dayan N, et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in the Adult. Can J Cardiol [Internet]. 2021 Mar 26 [cited 2021 Jun 29]; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0828282X21001653

- Gandhi J, Dagur G, Warren K, Smith NL, Sheynkin YR, Zumbo A, et al. The Role of Diabetes Mellitus in Sexual and Reproductive Health: An Overview of Pathogenesis, Evaluation, and Management. Curr Diabetes Rev [Internet]. 2017 Oct 11 [cited 2021 Aug 26];13(6). Available from: http://www.eurekaselect.com/147584/article

Abbreviations

2hPG 2-hour Plasma Glucose

A1C Glycosylated hemoglobin

ACR Albumin/Creatinine Ratio

ACEi Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

AHA’s Antihyperglycemic Agents

ARBs Angiotensin receptor blockers

ASA Acetylsalicylic Acid

ASCVD/CVD Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease/ Cardiovascular Disease

BMI Body Mass Index

CCS Canadian Cardiovascular Society

CGM Continuous Glucose Monitoring

CKD Chronic Kidney Disease

DM Diabetes Mellitus

DHP-CCB Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker

DPP-4i Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 Inhibitors

eGFR Creatinine/Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

FGM Flash Glucose Monitoring

FPG Fasting Plasma Glucose

GLP-1 Glucagon-like Peptide

HDL-C High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

HF Heart Failure

IFG Impaired Fasting Glucose

IGT Impaired Glucose Tolerance

LDL-C Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

MOBP Manual Office Blood Pressure

OGTT Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

SGLT2i Sodium-glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors

SMBG Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose

T2DM Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

TG Triglycerides

TZDs Thiazolidinediones

Practitioner Resources

Diabetes Canada has several resources for practitioners and can be found at: guidelines.diabetes.ca/health-care-provider-tools. They also have the Diabetes Canada 2018 CPG Webinar Series available at: guidelines.diabetes.ca/webinar

RACE: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program – www.raceconnect.ca

RACE means timely telephone advice from specialist for Physicians, Medical Residents, Nurse Practitioners, Midwives, all in one phone call.

Monday to Friday 0800 – 1700

Online at www.raceapp.ca or though Apple or Android mobile device. For more information on how to download RACE mobile applications, please visit www.raceconnect.ca/race-app/

Local Calls: 604–696–2131 | Toll Free: 1–877–696–2131

For a complete list of current specialty services visit the Specialty Areas page.

Pathways – PathwaysBC.ca

An online resource that allows GPs and nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. In addition, Pathways makes available hundreds of patient and physician resources that are categorized and searchable.

General Practice Services Committee – www.gpscbc.ca

- Practice Support Program: offers focused, accredited training sessions for BC physicians to help them improve practice efficiency and support enhanced patient care.

- Chronic Disease Management and Complex Care Incentives: compensates GPs for the time and skill needed to work with patients with complex conditions or specific chronic diseases.

Health Data Coalition: hdcbc.ca

An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist you in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing. HDC data can graphically represent patients in your practice with chronic kidney disease in a clear and simple fashion, allowing for reflection on practice and tracking improvements over time.

HealthLinkBC: healthlinkbc.ca

HealthLinkBC provides reliable non-emergency health information and advice to patients in BC. Information and advice on managing Diabetes in several languages is available by telephone, website, a mobile app and a collection of print resources.

People can speak to a health services navigator, registered dietitian, registered nurse, qualified exercise professional, or a pharmacist by calling 8-1-1 toll-free in B.C, or 7-1-1 for the deaf and hard of hearing.

See also Associated Documents: Diabetes Patient Care Flow Sheet

Patient, Family and Caregiver Resources

- Diabetes Canada: Tools and Resources

- HealthLinkBC: Managing Diabetes

-

Island Health Community Virtual Care: Community Virtual Care provides support to people with a range of medical conditions. Registered nurses help you to manage your condition from the comfort of your home. All the tools needed are loaned to you at no cost.

- Self-Management BC: Diabetes Self-Management Program

- iCON: Diabetes

Diagnostic code

250 - Diabetes mellitus

786 - Smoking cessation

783 - unhealthy eating and medical obesity

785 - physical inactivity

14066 - Personal health risk assessments

PG14050 – GPSC annual chronic care incentive (diabetes mellitus)

Appendices

- Appendix A: Screening Algorithm for Type 2 Diabetes in Adults (PDF, 101KB)

- Appendix B:Treatment of Hypoglycemia in Diabetes (PDF, 95KB)

- Appendix C: PharmaCare quantity limits for blood glucose test strips (PDF, 95KB)

- Appendix D: Commonly Used Antihyperglycemic Agents and Adjunctive Agents for Use in Type 2 Diabetes (PDF, 121KB)

- Appendix E: Insulin: Therapeutic Considerations and Availability (PDF, 129KB)

Associated Documents

Diabetes Patient Care Flow Sheet

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the effective date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee in collaboration with the Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services, and adopted under the Medical Services Act and the Laboratory Services Act.

For more information about how BC Guidelines are developed, refer to the GPAC Handbook available at BCGuidelines.ca: GPAC Handbook.

THE GUIDELINES AND PROTOCOLS ADVISORY COMMITTEE

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact Information: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee PO Box 9642 STN PROV GOVT Victoria, BC V8W 9P1 Email: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Website: www.BCGuidelines.ca

Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the guidelines) have been developed by the guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |