Hypertension - Diagnosis and Management

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Classification

- Epidemiology

- Detection

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Ongoing Care

- Controversies in Care

- Resources

- Appendices

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations on how to diagnose and manage hypertension (HTN) in adults. Management of secondary causes of HTN,* accelerated HTN, acute HTN in emergency settings, and HTN in pregnancy are out of scope.

For an algorithm of this guideline, refer to Appendix A: Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension Algorithm.

Key Recommendations †

Hypertension is a modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and an important public health issue.

Detection and Diagnosis

- When measuring blood pressure in the office, the use of an automated office blood pressure (AOBP) electronic device is recommended in patients with regular heart rate.1–3 [Strong Recommendation, Strong Evidence]

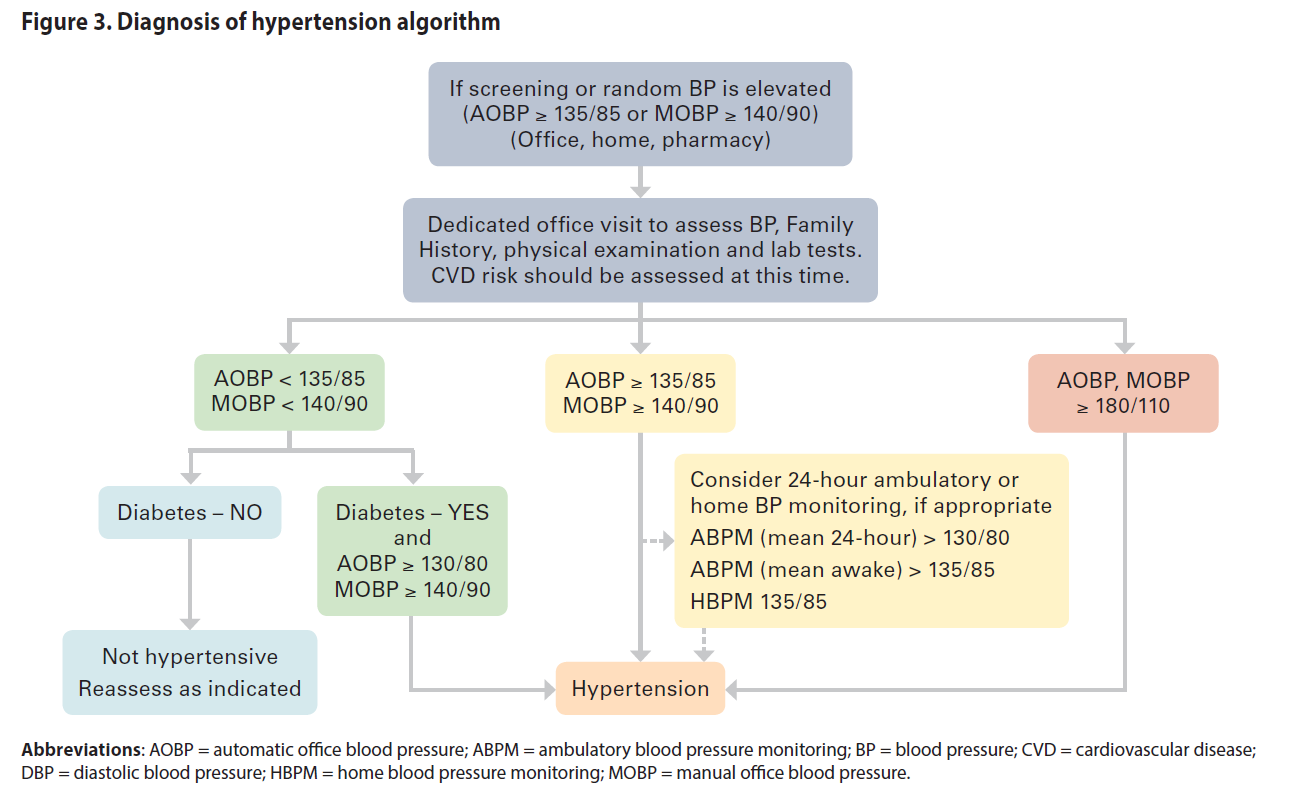

- Hypertension is diagnosed in adults when automated office blood pressure reading is ≥ 135/85 in the higher BP arm. [Strong Recommendation, Strong Evidence]

When a manual office blood pressure device (MOBP) is used hypertension is diagnosed at ≥ 140/90. 4–6 [Strong Recommendation, Strong Evidence] - Consider 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, or standardized home blood pressure monitoring, to confirm a hypertension diagnosis in all patients7. [Strong Recommendation, Strong Evidence]

Management

- A desired blood pressure level should be determined with each adult patient. Achieving an automated blood pressure reading of ≤ 135/85 is associated with the greatest reduction of risk for adults with no co-morbid conditions.8–10 [Strong Recommendation, Strong Evidence]

- Health behaviour change is recommended as a first step for those with average blood pressure 135-154/85-94 (AOBP), low-risk for cardiovascular disease and no co-morbidities.11 [Strong Recommendation, Strong Evidence]

- Initiate pharmaceutical management in context of the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk and not solely on their blood pressure.12,13 [Strong Recommendation, Strong Evidence]

Definitions

An elevated automated office blood pressure (AOBP) is defined as an average systolic blood pressure (SBP) of > 135 mm Hg or an average diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of > 85 mm Hg or both with best available technique.

White-coat hypertension refers to the untreated condition in which BP is elevated in the office but is normal when measured by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), home blood pressure measurement (HBPM), or both.

Masked hypertension refers to untreated patients in whom the BP is normal in the office but is elevated when measured by HBPM or ABPM.

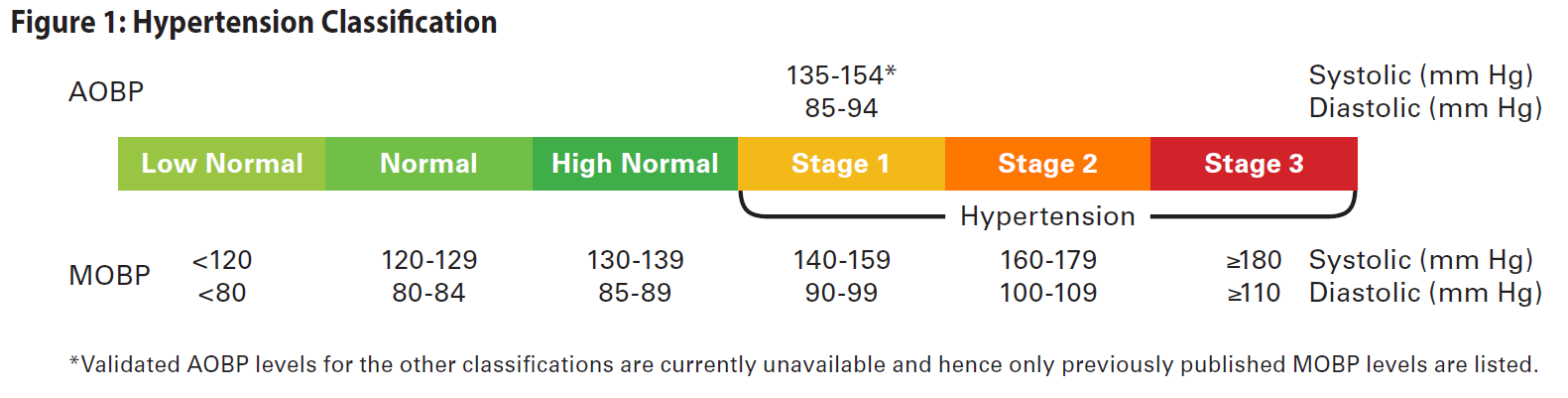

Classification

Based on the average BP recorded, hypertension is classified as High-Normal, Stage 1, Stage 2, or Stage 3 (Note: Figure 1 lists MOBP values only for Stage 2 and 3 since validated AOBP levels are currently unavailable). Management of hypertension based on the classification should be further informed and guided by the patient’s CVD risk, organ damage, and presence of co-morbidities.

Epidemiology

In BC, the age standardized prevalence rate for hypertension is 22.5 (per 100) and the age standardized annual incidence rate is 20.2 (per 1000 people over the age of 20) for 2017/18.14

Detection

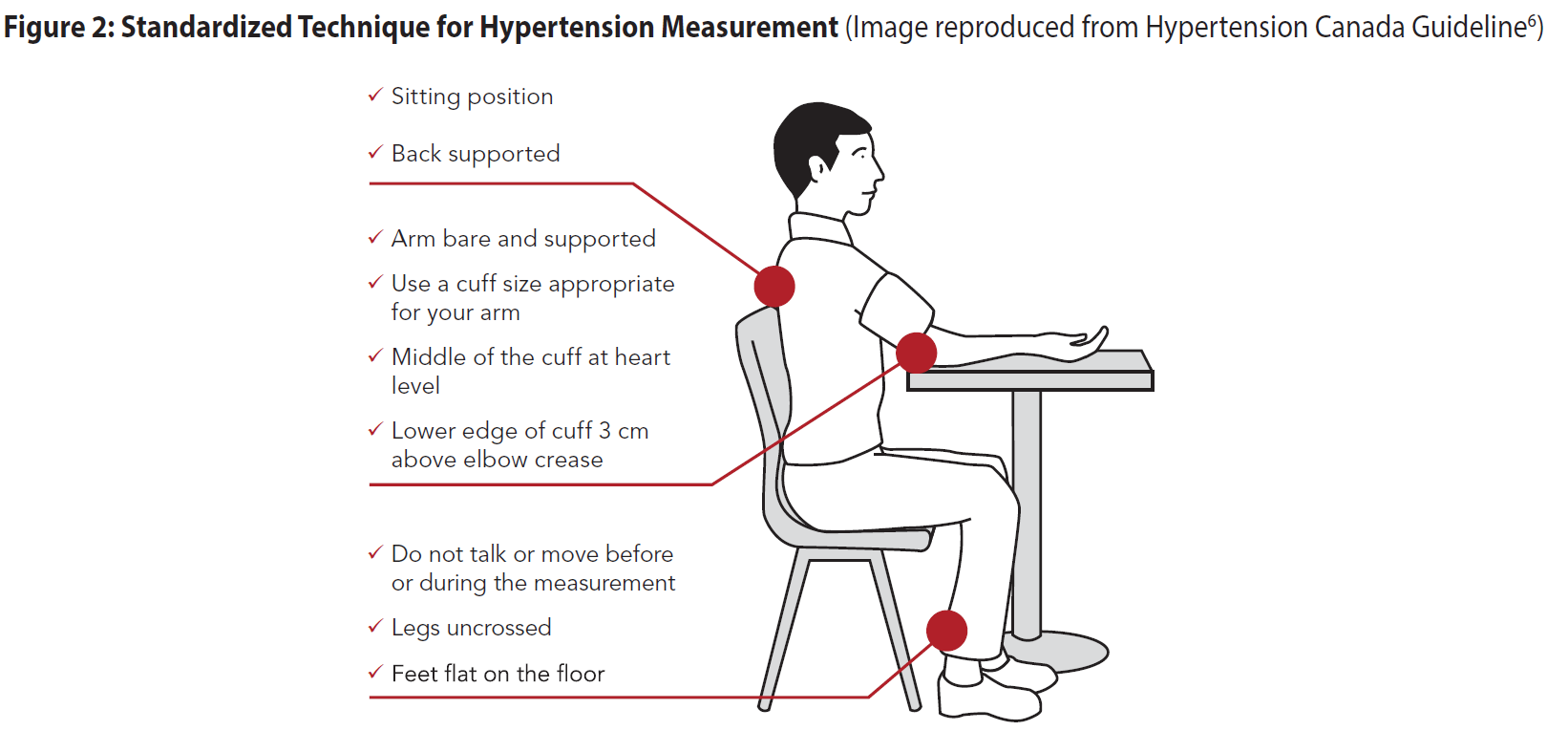

Screening blood pressure should be recorded as accurately as possible in all adults at every appropriate visit. At appropriate visits, ask permission to check BP on all adults (trauma-informed practice). Inform patients that they may be sensitive to the tightening of the cuff on their arm. Ensure standardized technique for measurement of BP (see Figure 2) and equipment are being used (see Table 1 in Appendix B: Recommended Methods and Techniques for Measuring Blood Pressure).3,15.

Diagnosis

Assessment of Blood Pressure

- Automated office BP measuring electronic device is recommended, in preference to manual office BP technique. Using automated office BP reduces errors and avoids an overestimation of BP values (white-coat HTN), underestimation of BP values (masked HTN), reduces threshold avoidance (where the BP reading is adjusted to avoid thresholds that entails making a diagnosis) and digit preference (rounding their BP recording to a nearest zero end-digit).2,16,17 The advantages and limitations of the different methods are listed in Appendix B: Recommended Methods and Techniques for Measuring Blood Pressure – Table 1.

- Assessment of postural hypotension should be included for appropriate patients (e.g., elderly).

- Ensure patient has not consumed caffeine or smoked in the last 30 minutes. Measure BP in both arms with the patient in a seated position resting quietly for at least 5 mins prior to measuring. Select the arm with the higher reading for further measurements. If average AOBP using the arm with the higher reading exceeds threshold for Hypertension diagnosis, proceed to investigations and work-up to assess target organ damage and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. If still using manual office technique, measure BP three more times using the arm with the higher reading, then discard the 1st reading and average the latter two.

- Consider 24 hour ambulatory or home BP monitoring for patients with borderline or variable measurements, significant anxiety or white coat syndrome.18

Table 1: Definition of Hypertension (in uncomplicated patients without co-morbidities)

| Definition of Hypertension according to measurement method | SBP mm Hg |

DBP mm Hg (and/or) |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Office BP (AOBP) | ≥135 | ≥85 |

| Manual Office BP (MOBP) | ≥140 | ≥90 |

| Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) | ||

| Daytime (awake) mean | ≥135 | ≥85 |

| Night-time (asleep) mean | ≥120 | ≥70 |

| 24 hr mean | ≥130 | ≥80 |

| Home blood pressure measurement (HBPM) mean | ≥135 | ≥85 |

Evaluation and Investigations

Medical history

Collect personal and family medical history to identify risk factors and potential secondary causes of hypertension (See Appendix C: Examples of Secondary Causes of Hypertension).

Risk Factors

- Modifiable: smoking; high alcohol consumption; low physical activity levels/sedentary lifestyle; unhealthy eating (such as high sodium intake and low vegetable and fruit intake); body composition (e.g., high body weight, high body mass index, waist circumference); poor sleep; poor psychological factors (e.g., stress levels).

- Non-modifiable: age; family history; ethnicity (e.g., African, Caribbean, South Asian including East Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan origin)

- Prescription drugs (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, decongestants, oral contraceptive use); others (e.g., alcohol, stimulants, sodium).

Indications for a secondary cause of hypertension

- Severe or refractory hypertension;

- An acute rise over previously stable values;

- Age < 30 years without family history; and/or

- No nocturnal fall in blood pressure (BP) during a 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring period.

Refer to Appendix C: Examples of Secondary Causes of Hypertension for more details.

Physical examination

- Weight, height, waist circumference, dilated fundoscopy, central and peripheral cardiovascular examination, and abdominal examination.

Laboratory tests

- Urinalysis - albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR), hematuria

- Blood chemistry - potassium, sodium, creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)

- Fasting blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c level

- Blood lipids – non-HDL cholesterol and triglycerides (non-fasting is acceptable)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) standard 12-lead

Cardiovascular Risk Assessment

Administer a Cardiovascular Risk Assessment using one of the several assessment tools available, including the Framingham Risk Score ( for patients age ≤74), Qrisk risk calculator (for patients age ≤84), Absolute CVD Risk/Benefit Calculator (for patients age ≤80). It is recommended to be familiar with at least one of the tools to predict CVD risk.

- CVD risk assessment tools can provide only an approximate CVD risk value and clinical judgement is essential in the interpretation of the scores. Some tools (e.g., QRISK2) may not provide accurate risk scores when co-morbidities such as non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus is present.19

- Use of risk assessment tools is not recommended for those with type 1 diabetes mellitus20 or chronic kidney disease due to the known increased risk of CVD in this group21.

Refer to BCGuidelines.ca: Cardiovascular Disease – Primary Prevention for further information on cardiovascular risk.

Indications for Consultation

Indications for consultation with a specialist include:

- Hypertensive emergency – DBP > 130 or BP > 180/110 with signs/symptoms§;

- Sudden onset in the elderly;

- Abnormal nocturnal BP differences18 – an extreme nocturnal BP dip (>20%), non/small nocturnal BP dip (<10%), or an increase in nocturnal BP are at risk for CVD;

- Signs or symptoms suggesting of secondary causes of the HTN (See Appendix C: Examples of Secondary Causes of Hypertension);

- Resistant HTN – Not achieving desired BP despite considerable treatment effort; and

- More than 15 mm Hg difference between the arms.

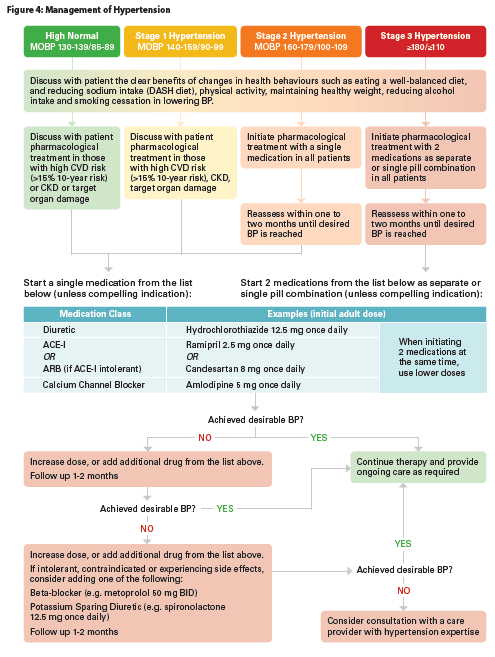

Management

Once a diagnosis has been confirmed, conduct a patient-centred discussion to agree upon desirable BP readings and an individualized treatment plan. Engage the patient in committing towards changes in lifestyle to lower their BP and informed decisions on pharmacological interventions. This discussion should consider any benefits and potential harms.

Desirable Blood Pressure Readings

AOBP less than 135/85 is the desirable blood pressure reading for an adult with no comorbid conditions, diabetes, chronic kidney disease or other target organ damage.4–6,8 However, an individual patient’s desirable BP is influenced by their age, presence of target organ damage, CVD risk level and/or the presence of other CVD risk factors (refer to BCGuidelines.ca: Cardiovascular Disease – Primary Prevention) and influenced by patient preferences, medication side effects and medication compliance.

This guideline uses the term 'desirable BP' instead of ‘targets’ to encourage individualized and patient-centred care. The suggested desirable BP readings of ≤135/85 is provided as guidance only, since recommending a uniform threshold for all patients or even patient groups is not optimal. Also, the term 'targets' is not used because the treat-to-target approach is not recommended.

Healthy Behaviours

Recommend health behaviour changes for all patients with hypertension. The benefits of healthy behaviours such as smoking cessation, decreasing alcohol intake, increasing physical activity, obtaining or maintaining a healthy body composition, eating a well-balanced diet, and monitoring sodium intake has been shown to have clear benefits for high normal, stage I, and stage II hypertensive patients.22,23

Patients in B.C. can access registered dietitian and exercise physiologist services by calling 8-1-1. Patient resources on lowering blood pressure are available through HealthLinkBC - Lifestyle Steps to Lower Your Blood Pressure (www.healthlinkbc.ca). Additional links for patient resources are available under Practitioner Resources and in 'A Guide for Patients: Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension'.

Health behaviour modification is recommended as a first line intervention for those in the high normal group (125/75-134/84 mm Hg) and those with stage I and II hypertension with <15% 10-year CVD risk. Recent meta-analyses

and clinical trials showed pharmacologic treatment in the high-normal group and stage I and stage II group without established CVD and low to moderate CVD risk only minimally reduced the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and no reduction in all-cause mortality and coronary heart disease.4,5,12,13,24,25

Table 2. Impact of health behaviours on blood pressure23,26

| Intervention | SBP (mm Hg) |

DBP (mm Hg) |

Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

DASH dietb |

-11.4 | -5.5 | |

|

Weight control |

-6.0 | -4.8 |

|

|

Reduced salt/sodium intake |

-5.4 | -2.8 |

|

|

Reduced alcohol intake (heavy drinkers) |

-3.4 | -3.4 |

|

|

Physical activity |

-3.1 | -1.8 |

|

|

Smoking cessation |

- | - |

|

|

Relaxation therapies |

-3.7 | -3.5 | - |

|

Multiple interventions |

-5.5 | -4.5 | - |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; DASH = dietary approaches to stop hypertension; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; kg/m2 = kilogram per square metre; mm Hg = millimetre of mercury; SBP = systolic blood pressure; WC = waist circumference.

Footnotes: a Hypertension Canada now recommends a salt/sodium intake threshold 2000 mg (5 g of salt/sodium) per day. The previous threshold was ≤ 1500 mg (3.75 g of salt/sodium) and was changed based on clinical trial evidence from two systematic reviews published in 2013. The aim is to identify salt sensitive patients. b There are no mortality outcome studies of the DASH diet.

Pharmacologic Management

Instigate pharmaceutical management in context of the patient’s overall CVD risk (e.g., not solely based on a patient’s BP) and in conjunction with health behaviour change.27,28

Pharmacologic management should be considered in addition to lifestyle management if:

- average BP is > 135/85 with target organ damage or CVD risk >15%;

- average BP is > 135/85 with 1+ co-morbidities (refer to Table 4 for co-morbidities list);

- average BP is ≥ 160/100; or

- desirable BP is not reached with health behaviour change.

Treatment of Hypertension without Specific Indications

When prescribing, take into account cost of the drug, any potential side-effects and any contraindications.25,29–31

Without specific indications, consider monotherapy or single pill combination with one of the following first-line drugs32:

- low-dose thiazides and thiazide-like diuretic;

- long-acting calcium channel blocker (CCB);

- angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I; in non-black patients); or

- angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB).

Table 3. Contraindications for antihypertensive medications

| Drug | Contraindications | Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors Angiotensin II receptor blocker |

Pregnancy History of angioedema Bilateral renal artery stenosis |

Electrolyte imbalances Severe renal impairment |

| Beta-blockers | Second- or third-degree AV block Sick sinus syndrome or SA block Bradycardia Decompensated HF Severe peripheral arterial circulatory disorders |

Athletes and physically active patients Asthma (non-selective BBs) |

| Calcium Channel Blockers – Dihydropyridine (e.g., amlodipine) | Heart Failure Pre-existing severe leg edema Severe aortic stenosis Chronic constipation |

|

| Thiazides and Thiazide-like diuretics | Anuria | Gout Glucose intolerance Electrolyte imbalances Significant hepatic disease |

Among these, thiazide diuretics are the least costly agents. Evidence suggests a non-significant difference in CV events and all-cause mortality between chlorthalidone and hydrochlorothiazide.33,34 In a recent meta analysis of routinely collected health data, chlorthalidone was associated with a significantly higher risk of hypokalemia, hyponatremia, acute renal failure, chronic kidney disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus when compared to hydrochlorothiazide.35

Note that alpha-blockers and beta-blockers are no longer considered to be a first-line option.36

If desirable BP is not achieved with standard-dose monotherapy, use combination therapy by adding one or more of the first-line drugs. Combination of ACE-I and ARB is not recommended, and caution with combining a non-dihydropyridine CCB (i.e., verapamil or diltiazem) and a beta-blocker.

For a list of commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications in each class, refer to Appendix D: Commonly Used Antihypertensive Drugs.

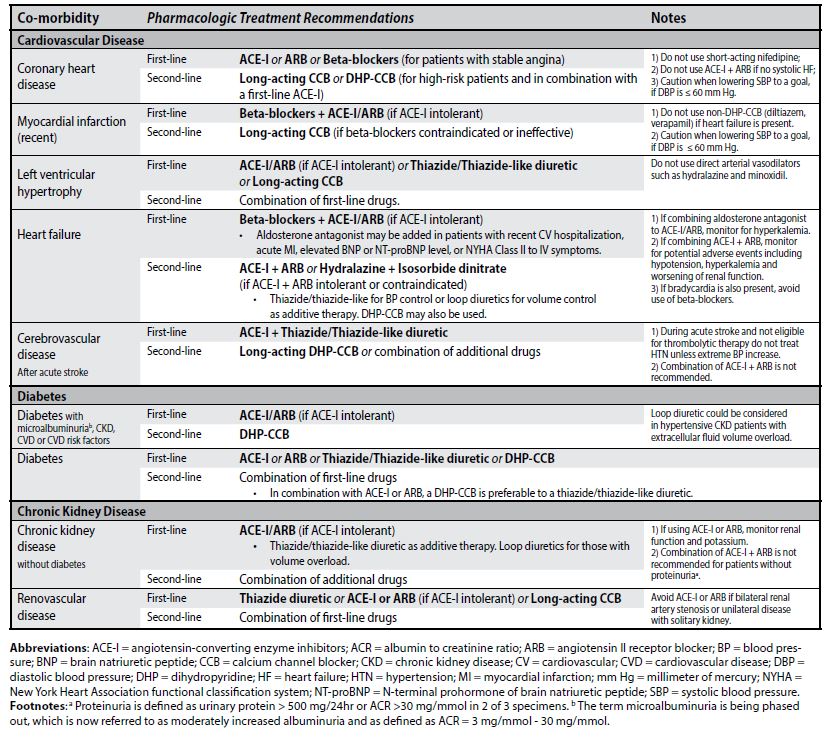

Treatment of Hypertension with Specific Indications

Selecting an antihypertensive drug for a patient with 1+ co-morbidities may require a specific first-line drug. Refer to Table 4 for recommended first-line and second-line treatments.

Table 4. Pharmacologic treatment recommendations of hypertension complicated by co-morbidity7

Follow-up to Treatment

Two weeks after initiating antihypertensive medications, follow-up with an eGFR to monitor kidney function and monitor for adherence to medications. Then, follow-up with the patient at monthly intervals until BP is in a desired range for two consecutive visits. Review every 3 - 6 months (as long as the patient remains stable). Establish the minimum dose of medication required to achieve the desired BP and reassess medication adherence with patients prior to adding/increasing medications. Periodically, consider discontinuing or reducing antihypertensive medications to assess the appropriate level of pharmacologic management. Monitor kidney function whenever medications are changed (e.g., dose adjustments).

Ongoing Care

Implement self-management strategies to assist the patient in managing their BP including measurement of their BP at home, committing to healthy behaviours and appropriate use of medications. At least annually, review the patient’s medication, lifestyle change behaviours, risk factors, and examine for evidence of target organ damage.

Controversies in Care

Blood Pressure Readings in Population with Diabetes: For patients with diabetes, reaching a desirable MOBP reading of <130/80 is recommended by Hypertension Canada, American College of Cardiology, European Society of Hypertension and the Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines. The desired level of MOBP <130/80 was determined by these groups following review of several recent clinical trials that support lower BP levels with reductions in risk of microvascular diabetic endpoints, stroke and major cardiovascular events.11,37

Chronic Kidney Disease: For those diagnosed with chronic kidney disease a BP reading of AOBP < 135/85 is recommended as a desired level. Although there are differences in recommended BP targets for this population between the American College of Cardiology and of Hypertension Canada and the European Society of Hypertension, our recommendations align with the latter as the current evidence failed to show improved clinical outcomes for BP targets < 125/75 compared to < 135/85.9,38,39

Older Adults: For adults aged 60 and above desirable BP reading of AOBP < 145/85 is recommended. Treating older adults to < 145/85 has been shown to significantly reduce mortality, stroke and cardiac events. BP targets lower than < 145/85 maybe beneficial for some (such as those with high cardiovascular risk) however clinical outcomes vary between trials.40–42

A paradoxical relationship between lower BP and increased mortality in older adults has been suggested to be explained by frailty.43 Elevated BP is associated with greater mortality in fit persons whereas in frail persons higher BP was associated with lower mortality risk (e.g., National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey44). The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force provides no specific recommendation on treatment for this population due to the lack of evidence.45

Finally, frailty is associated with limited life expectancy. Therefore, the time-until-benefit of a given treatment might exceed the life expectancy in frail individuals and may modify the risk–benefit ratio of preventive treatments for chronic diseases, including hypertension.43

Hydrochlorothiazide and Skin Cancer Association:

At this time, substantial uncertainty exists around the evidence on the link between Hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) and skin cancer. Although photosensitivity is a known rare adverse reaction of HCTZ, and patients are advised of possible skin reactions such as sunburn, premature aging, and rash, malignancy is not one of them. Patients should be advised of the potential risk. Advise patients to regularly check for skin lesions, limit sun exposure and use adequate sun protection. Engage in shared-decision making with patients to find alternative medications especially in those with high risk for non-melanoma skin cancer.46

HCTZ is a commonly prescribed medication for hypertension. In January of 2019, Health Canada issued a safety alert that concluded that prolonged use of HCTZ may be associated with a risk of non-melanoma skin cancer that is at least four times the risk of not using HCTZ.46 The evidence for this safety alert came from 2 published studies from Denmark where nested case-control studies using the National database suggested a link between HCTZ use and the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) and cutaneous basal cell carcinoma (cBCC) (non-melanoma skin cancers). The studies suggested that high use of HCTZ (i.e., >3 years) could lead to 122 more (95% CI, from 112 more to 133 more) cases of cSCC per 1000 treated patients compared with its non-use (meta-analysis of 3 observational studies; very low certainty evidence) and 31 more (95% CI, from 24 more to 37 more) cases of cBCC per 1000 treated patients compared with its non-use (meta-analysis of 2 observational studies; very low certainty evidence).47,48

Resources

References

- Final Recommendation Statement: High Blood Pressure in Adults: Screening - US Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. [cited 2019 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/announcements/final-recommendation-statement-screening-high-blood-pressure-adults

- Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing Automated Office Blood Pressure Readings With Other Methods of Blood Pressure Measurement for Identifying Patients With Possible Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Mar 1;179(3):351.

- Kollias A, Stambolliu E, Kyriakoulis KG, Gravvani A, Stergiou GS. Unattended versus attended automated office blood pressure: Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using the same methodology for both methods. J Clin Hypertens Greenwich Conn. 2019 Feb;21(2):148–55.

- Saiz LC, Gorricho J, Garjón J, Celaya MC, Erviti J, Leache L. Blood pressure targets for the treatment of people with hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Hypertension Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2018 Jul 20 [cited 2019 May 14]; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD010315.pub3

- Brunström M, Carlberg B. Association of Blood Pressure Lowering With Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease Across Blood Pressure Levels. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan;178(1):28–36.

- Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, Dasgupta K, Butalia S, McBrien K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2018 Guidelines for Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults and Children. Can J Cardiol. 2018 May;34(5):506–25.

- Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, Margolis KL, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP. Diagnostic and Predictive Accuracy of Blood Pressure Screening Methods With Consideration of Rescreening Intervals: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Feb 3;162(3):192.

- Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, Ng M, Biryukov S, Marczak L, et al. Global Burden of Hypertension and Systolic Blood Pressure of at Least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990-2015. JAMA. 2017 10;317(2):165–82.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1;39(33):3021–104.

- Thomopoulos C, et al.,. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension. 1. Overview, meta-analyses, and meta-regression analyses of randomized tri... - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 13]. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.hlth.gov.bc.ca/pubmed/25255397

- Reboussin David M., Allen Norrina B., Griswold Michael E., Guallar Eliseo, Hong Yuling, Lackland Daniel T., et al. Systematic Review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018 Jun 1;71(6):e116–35.

- Lonn EM, Bosch J, López-Jaramillo P, Zhu J, Liu L, Pais P, et al. Blood-Pressure Lowering in Intermediate-Risk Persons without Cardiovascular Disease [Internet]. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1600175. 2016 [cited 2019 May 15]. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1600175?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Musini VM, Gueyffier F, Puil L, Salzwedel DM, Wright JM. Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Apr 3];(8). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008276.pub2/full

- British Columbia Ministry of Health [data provider]. BC Observatory for Population and Public Health [publisher]. Chronic Disease Dashboard. Available at: http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/disease-system-statistics/chronic-disease-dashboard.

- Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, Charleston JB, Gaillard T, Misra S, et al. Measurement of Blood Pressure in Humans: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension [Internet]. 2019 May [cited 2019 May 17];73(5). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087

- Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, Burrello J, D’Ascenzo F, Veglio F, et al. Comparison of Automated Office Blood Pressure With Office and Out-Off-Office Measurement Techniques. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. 2019 Feb;73(2):481–90.

- Greiver M, Kalia S, Voruganti T, Aliarzadeh B, Moineddin R, Hinton W, et al. Trends in end digit preference for blood pressure and associations with cardiovascular outcomes in Canadian and UK primary care: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2019 Jan;9(1):e024970.

- Yang W-Y, Melgarejo JD, Thijs L, Zhang Z-Y, Boggia J, Wei F-F, et al. Association of Office and Ambulatory Blood Pressure With Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes. JAMA. 2019 Aug 6;322(5):409–20.

- Read SH, Diepen M van, Colhoun HM, Halbesma N, Lindsay RS, McKnight JA, et al. Performance of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Scores in People Diagnosed With Type 2 Diabetes: External Validation Using Data From the National Scottish Diabetes Register. Diabetes Care. 2018 Sep 1;41(9):2010–8.

- Schofield J, Ho J, Soran H. Cardiovascular Risk in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2019 Jun;10(3):773–89.

- Major RW, Cheng MRI, Grant RA, Shantikumar S, Xu G, Oozeerally I, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2018 Mar 21;13(3):e0192895.

- Aronow WS. Lifestyle measures for treating hypertension. Arch Med Sci AMS. 2017 Aug;13(5):1241–3.

- Hypertension Canada. Hypertension Canada. Health Behaviour Management [Internet]. Available from: https://guidelines.hypertension.ca/preventiontreatment/health-behaviour-management/

- Diao D, Wright JM, Cundiff DK, Gueyffier F. Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Apr 3];(8). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006742.pub2/full

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood-pressure-lowering treatment on outcome incidence. 12. Effects in individuals with high-normal and normal blood pressure: overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2017;35(11):2150–60.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Hypertension: The Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults: Update of Clinical Guidelines 18 and 34 [Internet]. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2011 [cited 2019 May 16]. (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83274/

- Karmali KN, Lloyd-Jones DM, van der Leeuw J, Goff DC, Yusuf S, Zanchetti A, et al. Blood pressure-lowering treatment strategies based on cardiovascular risk versus blood pressure: A meta-analysis of individual participant data. PLoS Med. 2018;15(3):e1002538.

- Blood pressure-lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. The Lancet. 2014 Aug 16;384(9943):591–8.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure-lowering treatment on cardiovascular outcomes and mortality: 14 - effects of different classes of antihypertensive drugs in older and younger patients: overview and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2018;36(8):1637–47.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure-lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 5. Head-to-head comparisons of various classes of antihypertensive drugs – overview and meta-analyses. J Hypertens. 2015 Jul 1;33(7):1321–41.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood-pressure-lowering treatment in hypertension: 9. Discontinuations for adverse events attributed to different classes of antihypertensive drugs meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2016 Oct 1;34(10):1921–32.

- Wright JM, Musini VM, Gill R. First‐line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 3];(4). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub3/full

- Olde Engberink Rik H.G., Frenkel Wijnanda J., van den Bogaard Bas, Brewster Lizzy M., Vogt Liffert, van den Born Bert-Jan H. Effects of Thiazide-Type and Thiazide-Like Diuretics on Cardiovascular Events and Mortality. Hypertension. 2015 May 1;65(5):1033–40. BCGuidelines.ca: Hypertension – Diagnosis and Management (2020)

- Liang W, Ma H, Cao L, Yan W, Yang J. Comparison of thiazide‐like diuretics versus thiazide‐type diuretics: a meta‐analysis. J Cell Mol Med. 2017 Nov;21(11):2634–42.

- Hripcsak G, Suchard MA, Shea S, Chen R, You SC, Pratt N, et al. Comparison of Cardiovascular and Safety Outcomes of Chlorthalidone vs Hydrochlorothiazide to Treat Hypertension. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 17;

- Wiysonge CS, Bradley HA, Volmink J, Mayosi BM, Opie LH. Beta-blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Hypertension Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2017 Jan 20 [cited 2019 May 15]; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub5

- Tobe SW, Gilbert RE, Jones C, Leiter LA, Prebtani APH, Woo V. Treatment of Hypertension. Can J Diabetes. 2018 Apr;42:S186–9.

- Malhotra R, Nguyen HA, Benavente O, Mete M, Howard BV, Mant J, et al. Association Between More Intensive vs Less Intensive Blood Pressure Lowering and Risk of Mortality in Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 3 to 5: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Oct 1;177(10):1498–505.

- Upadhyay A, Earley A, Haynes SM, Uhlig K. Systematic review: blood pressure target in chronic kidney disease and proteinuria as an effect modifier. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Apr 19;154(8):541–8.

- Garrison SR, Kolber MR, Korownyk CS, McCracken RK, Heran BS, Allan GM. Blood pressure targets for hypertension in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Apr 5];(8). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011575.pub2/full

- Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, Fu R, Kerfoot A, Paynter R, et al. Benefits and Harms of Intensive Blood Pressure Treatment in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Mar 21;166(6):419.

- The SPRINT Research Group. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373(22):2103–16.

- Vetrano DL, Palmer KM, Galluzzo L, Giampaoli S, Marengoni A, Bernabei R, et al. Hypertension and frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018 Dec;8(12):e024406.

- Odden MC, Peralta CA, Haan MN, Covinsky KE. Rethinking the Association of High Blood Pressure with Mortality in Elderly Adults: The Impact of Frailty. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Aug 13;172(15):1162–8.

- Whelton Paul K., Carey Robert M., Aronow Wilbert S., Casey Donald E., Collins Karen J., Dennison Himmelfarb Cheryl, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018 Jun 1;71(6):1269–324.

- Health Canada. Important new safety information regarding the use of hydrochlorothiazide and the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 25]. Available from: https://healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2019/68976a-eng.php

- Pedersen SA, Gaist D, Schmidt SAJ, Hölmich LR, Friis S, Pottegård A. Hydrochlorothiazide use and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer: A nationwide case-control study from Denmark. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(4):673-681.e9.

- Pottegård A, Pedersen SA, Schmidt SAJ, Hölmich LR, Friis S, Gaist D. Association of Hydrochlorothiazide Use and Risk of Malignant Melanoma. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Aug 1;178(8):1120–2.

Practitioner Resources

- RACE: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program – www.raceconnect.ca

A telephone consultation line for select specialty services for physicians, nurse practitioners and medical residents. If the relevant specialty area is available through your local RACE line, please contact them first. Contact your local RACE line for the list of available specialty areas. If your local RACE line does not cover the relevant specialty service or there is no local RACE line in your area, or to access Provincial Services, please contact the Vancouver/Providence RACE line.- Vancouver Coastal Health Region/Providence Health Care: www.raceconnect.ca

604-696-2131 (Vancouver) or 1-877-696-2131 (toll free)

Available Monday to Friday, 8 am to 5 pm - Northern RACE: 1-877-605-7223 (toll free)

- Kootenay Boundary RACE: www.divisionsbc.ca/kb/race 1-844-365-7223 (toll free)

- For Fraser Valley RACE: www.raceapp.ca (download at Apple and Android stores)

- South Island RACE: www.raceapp.ca (download at Apple and Android stores) or

see www.divisionsbc.ca/south-island/RACE

- Vancouver Coastal Health Region/Providence Health Care: www.raceconnect.ca

- Health Data Coalition: https://hdcbc.ca/

An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist you in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing. HDC data can graphically represent patients in your practice with chronic diseases in a clear and simple fashion, allowing for reflection on practice and tracking improvements over time.

- Hypertension Canada, www.hypertension.ca

- BIHS - The British and Irish Hypertension Society, bihsoc.org

- Heart and Stroke Foundation, www.heartandstroke.ca

- The DASH Diet: Heart and Stroke Foundation: www.heartandstroke.ca/dash-diet

- The DASH Diet: Heart and Stroke Foundation: www.heartandstroke.ca/dash-diet

- BC Guidelines - www.BCGuidelines.ca - Cardiovascular Disease – Primary Prevention (2014)

- HealthLink BC, www.healthlinkbc.ca. You may call HealthLinkBC at 8-1-1 toll-free in B.C., or for the deaf and the hard of hearing, call 7-1-1. You will be connected with an English speaking health-service navigator, who can provide health and health-service information and connect you with a registered dietitian, exercise physiologist, nurse, or pharmacist.

- HealthLinkBC, Lifestyle Steps to Lower Your Blood Pressure

- HealthLink BC: DASH Diet Sample Menu www.healthlinkbc.ca/DASH Diet

- Island Health Community Virtual Care: Community Virtual Care provides support to people with a range of medical conditions. Registered nurses help you to manage your condition from the comfort of your home. All the tools needed are loaned to you at no cost.

- Quit Smoking: QuitNow.ca provides one-on-one support and valuable resources in multiple languages to help you plan your strategy and connect with a Quit Coach.

Phone: 1-877-455-2233 (toll-free) Email: quitnow@bc.lung.ca - The BC Smoking Cessation Program helps cover the cost of nicotine replacement therapy products (nicotine gum, lozenges, patches, inhaler) and specific smoking cessation prescription drugs (Zyban® or Champix®). For prescription medications to help you quit smoking, speak to your doctor.

- For more information about reducing alcohol intake

- Refer to Canada’s Low Risk Drinking Guidelines – also available at HealthLink BC: Alcohol: Drinking and Your Health

- Refer to BC Guidelines - www.BCGuidelines.ca - Problem Drinking (2013) – under revision in collaboration with BC Centre on Substance Use (www.bccsu.ca)

- BC Centre on Substance Use has recently published guidance on supporting those living with alcohol addiction.

- A Provincial Guideline for the Clinical Management of High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder (December 2019; www.bccsu.ca/aud-guideline)

- A Guideline for the Clinical Management of High-Risk Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder (December 2019; www.bccsu.ca/aud-recommendations)

Appendices

- Appendix A: Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension Algorithm (PDF, 109KB)

- Appendix B: Recommended Methods and Techniques for Measuring Blood Pressure (PDF, 115KB)

- Appendix C: Examples of Secondary Causes of Hypertension (PDF, 109KB)

- Appendix D: Commonly Used Antihypertensive Drugs (PDF, 160KB)

- Appendix E: Hypertension Quality Indicators (PDF, 96KB)

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

- Summary of Guideline: Hypertension – Diagnosis and Management (PDF, 95.2KB)

- A Guide for Patients: Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension (PDF, 210KB)

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the effective date.

The guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

For more information about how BC Guidelines are developed, refer to the GPAC Handbook available at BCGuidelines.ca: GPAC Handbook.

THE GUIDELINES AND PROTOCOLS ADVISORY COMMITTEE

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact Information Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee E-mail: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |

TOP

TOP