Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)

Effective Date: January 18, 2023

Revised Date: January 4, 2024 [Minor revisions to reflect new PharmaCare coverage for Apixaban and FRAIL-AF randomized control trial results]

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Pharmacological Properties

- Therapeutic Indications

- Initiating a DOAC

- Ongoing Management

- Resources

- Appendices

This guideline provides recommendations on the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in adults aged >19 years for the following indications:

- prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF);

- treatment of hemodynamically stable venous thromboembolism (VTE); and,

- prevention of arterial vascular events in patients with stable coronary artery disease with or without peripheral artery disease.

How to make the decision to use a DOAC (instead of another anticoagulant), periprocedural management, and emergency reversal are all outside the scope of this guideline. Refer to BC Guidelines: Warfarin and BC Guidelines: Oral Anticoagulants: Elective Interruption & Emergency Reversal for more information on these topics.

- DOACs are considered first-line therapy for:

- prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) for whom anticoagulation is indicated; and

- treatment of hemodynamically stable venous thromboembolism (VTE).

- Do not use DOACs (instead of warfarin) for anticoagulation in mechanical heart valves, AF with moderate to severe mitral stenosis, and other very high-risk thrombotic indications.

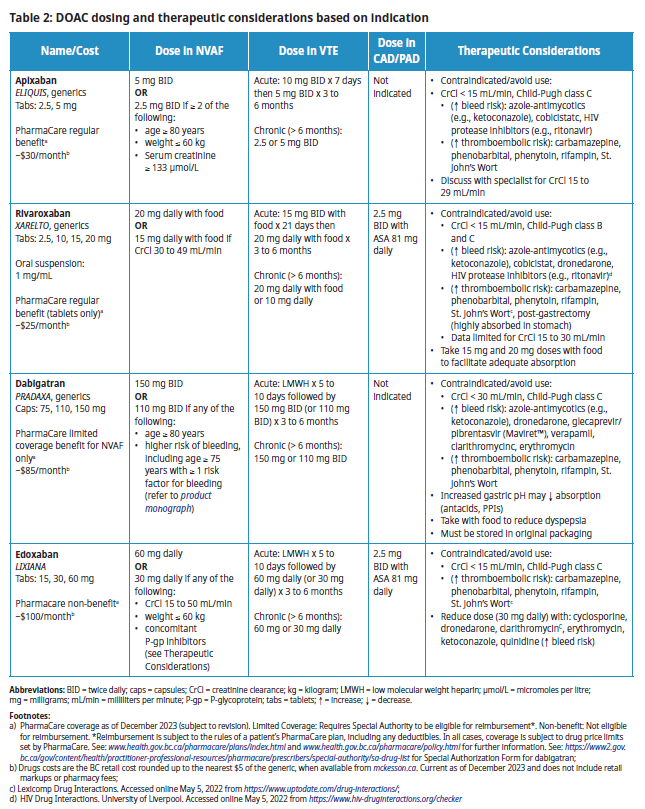

- Confirm appropriate dosing as this varies widely across different indications. Dose adjustments may be indicated for renal impairment, age, weight, and drug-drug interactions. Refer to Table 2: DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations based on indication and Appendix A: DOAC Drug Interactions for more information.

- Check renal function for all patients and liver function in patients with known hepatic dysfunction prior to initiating a DOAC. Monitor one or both periodically, based on clinical status.

- DOACs do not require routine laboratory monitoring. International normalized ratio (INR) and activated partial thromboplastin clotting time (aPTT) values do not reflect anticoagulant level or activity and should not be used to detect or exclude the presence of a DOAC.

- Check for potential drug-drug interactions and consider alternative therapy if a significant interaction is present.

DOACs are a class of drugs with potent anticoagulant effects. DOACs work by inhibiting key activated clotting factors in the coagulation cascade. There are four DOACs currently available in Canada: three activated factor X (FXa) inhibitors (apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban) and one direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran).

Pharmacological Properties

While DOACs have similar properties, their safety and suitability for individual patients differ based on each drug’s pharmacological profile.1,2 As a class, DOACs have relatively predictable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, including:

- Rapid onset of action, reaching therapeutic effect in less than 4 hours.

- Half-lives that are highly dependent on renal and/or liver function.

DOACs have fewer food and drug interactions as compared to warfarin.3 However there are many drugs that should not be used concomitantly with DOACs. Refer to Table 2: DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations based on indication and Appendix A: DOAC Drug Interactions for more information on therapeutic considerations and drug-drug interactions.

Therapeutic Indications

DOACs are approved in three major clinical settings where oral anticoagulation is commonly used, but are not preferred over warfarin for certain patient populations and are contraindicated for others (see the Initiating a DOAC section below for more information). Refer to Table 2: DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations based on indication for more detail on DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations based on indication and the Resources section for information on the Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise (RACE) program.

DOACs for Non-valvular Atrial Fibrillation (NVAF)

DOACs are considered first line treatment for most patients with NVAF (strong recommendation, high-quality evidence),4,5 based on direct comparison with warfarin in robust clinical trials investigating the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with NVAF.6–9 As a class, DOACs have been shown to be superior or non-inferior to warfarin in terms of efficacy,10,11 with reduced risk of stroke, intracranial bleeding, and all-cause mortality.10 DOACs also have comparable or better safety profiles, with no difference in major bleeding and a lower risk of intracranial bleeding.10 DOACs also offer important practical benefits for patients and providers (e.g., ease of administration, fewer dietary interactions, reduced monitoring requirements).

DOACs for Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

DOACs are considered first line treatment for acute VTE and prevention of recurrent VTE in most patients because of their overall safety profile and convenience when compared to warfarin.12–14 However, there is no difference in all-cause mortality, recurrent thrombosis or major bleeding between the use of DOACs and warfarin for VTE.14 Anticoagulant therapy for acute VTE is recommended for at least three months.15 Extended DOAC use in select patients (e.g., unprovoked index event or ongoing risk factors) beyond six months can reduce VTE recurrence and/or death when compared to a placebo,16 but it is associated with a higher risk of non-major clinically important bleeding.16

DOACs for Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) and Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD)

A very low dose of rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) combined with low-dose ASA once daily reduces the risk of cardiovascular death, stroke or myocardial infarction in patients with stable CAD and/or PAD.17,18 Recent data show that this combination is also effective in reducing major adverse limb and cardiovascular thrombotic events after endovascular intervention in patients with PAD; these outcomes include limb ischemia, amputation, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and death.19 However, the combination of very low dose rivaroxaban and low-dose ASA (dual pathway inhibition) is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding (primarily in the gastrointestinal tract) when compared to ASA alone, although no significant increase in fatal/ critical bleeding has been observed.17,20

Initiating a DOAC

Clinical Assessment

Before initiating a DOAC, ensure that the patient does not have a contraindication where warfarin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is recommended instead. Refer to Table 1: Absolute contraindications for DOACs for more information on DOAC contraindications and BC Guidelines: Warfarin for more general warfarin information. Of note, DOACs are not contraindicated in frail elderly populations; a risk-benefit analysis favours anticoagulation for patients with NVAF in this population.21

| Absolute Contraindication | Alternative Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Mechanical heart valve | Warfarin22 |

| Atrial fibrillation with moderate to severe mitral stenosis | Warfarin4 |

| Pregnancy | LMWH, especially during first trimester |

| Breastfeeding | LMWH or warfarin |

| Triple positive antiphospholipid syndrome23 | Refer to specialist for alternative management |

| Severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 50 x 109/L) | Refer to specialist for alternative management |

| Clinically significant drug-drug interactions | Refer to Table 2: DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations based on indication and Appendix A: DOAC Drug Interactions |

Abbreviations: LVMWH = low molecular weight heparin.

Specialty consultation is also recommended for certain patients where the evidence is weak or for patients at increased risk of adverse outcomes, including but not limited to:

- Severe kidney dysfunction (e.g., CrCl < 30 mL/min);

- Liver impairment (e.g., Child-Pugh Score class B or C, depending on specific DOAC);

- Active cancer;

- Extremes of bodyweight (e.g, body weight <40 or >120 kg; BMI £18.5 or ³35 kg/m2);24

- Post bariatric or extensive bowel surgery;

- Solid organ or stem cell transplant; and/or

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Refer to Table 2: DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations based on indication for more detail on DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations and a HIV drug checker for more information.

Consult with your local pharmacist regarding potential drug-drug interactions that may reduce DOAC efficacy or increase a patient’s risk of bleeding. Consider alternative therapy if any significant interaction is present. Of note, polypharmacy in elderly patients may increase risks of adverse outcomes from drug-drug interactions. Refer to Table 2: DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations based on indication for more details on DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations and Appendix A: DOAC Drug Interactions for more information on drug interactions.

Laboratory Testing

Complete blood count (CBC) and Creatinine Clearance (CrCl) must be checked for all patients prior to initiating a DOAC. The CrCl (calculated using Cockcroft-Gault formula) should be used to determine DOAC dosage according to the patient’s age, weight, and serum creatinine.25 Do not use the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) provided by laboratory reports as this can lead to inappropriate DOAC dosing in a significant proportion of patients. Liver function should also be checked in those with known hepatic dysfunction (e.g., cirrhosis, hepatitis) before starting a DOAC.

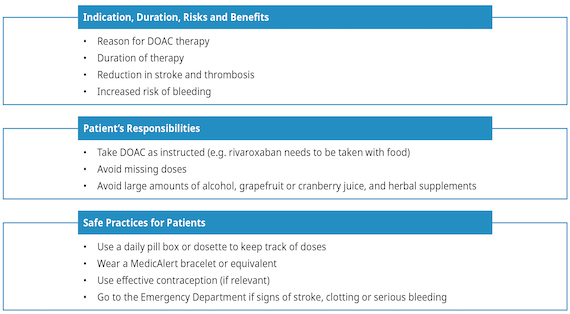

Patient Education

Patient education is an important component of drug initiation. Given that DOAC half-lives are relatively short (~12 hours), missing 1-2 doses can lead to subtherapeutic coverage and thus increased risk of stroke or recurrent thrombosis. Twice-daily DOACs (e.g., apixaban) may be more appropriate than once-daily DOACs (e.g., rivaroxaban) for patients for whom adherence is a concern.26

Dosage

The table below is not an exhaustive list of all contraindications, precautions, and drug interactions. Consult a drug interaction checker or pharmacist, as needed. Refer to the Resources section for Child-Pugh Score and Cockcroft-Gault calculators.

Table 2: DOAC dosing and therapeutic considerations based on indication

Abbreviations: BID = twice daily; caps = capsules; CrCl = creatinine clearance; kg = kilogram; LMWH = low molecular weight heparin; µmol/L = micromoles per litre; mg = milligrams; mL/min = milliliters per minute; P-gp = P-glycoprotein; tabs = tablets; = increase; ¯ = decrease.

Footnotes:

- PharmaCare coverage as of December 2023 (subject to revision). Limited Coverage: Requires Special Authority to be eligible for reimbursement*. Non-benefit: Not eligible for reimbursement. *Reimbursement is subject to the rules of a patient’s PharmaCare plan, including any deductibles. In all cases, coverage is subject to drug price limits set by PharmaCare. See: www.health.gov.bc.ca/pharmacare/plans/index.html and www.health.gov.bc.ca/pharmacare/policy.html for further information. See the Special Authority Drug List for the Special Authorization Form for dabigatran;

- Drugs costs are the BC retail cost rounded up to the nearest $5 of the generic, when available from mckesson.ca. Current as of December 2023 and does not include retail markups or pharmacy fees;

- Lexicomp Drug Interactions. Accessed online May 5, 2022 from https://www.uptodate.com/drug-interactions/;

- HIV Drug Interactions. University of Liverpool. Accessed online May 5, 2022 from https://www.hiv-druginteractions.org/checker

Switching Between Warfarin and a DOAC

There is no need to switch to a DOAC for patients, especially frail elderly, who are currently and successfully anticoagulated with warfarin. Changes in anticoagulant therapy are associated with a transient increased risk of stroke and systemic embolism.27 However, switching may be indicated for patients who are frequently outside the therapeutic INR range or those who cannot adhere to regular laboratory monitoring.28 Refer to Appendix B: Switching Between Warfarin and DOAC for recommended approaches to switching between anticoagulant therapies.

Ongoing Management

Clinical Follow-Up

Reassess patients within 1-2 months of DOAC initiation to assess adherence, review potential adverse events (e.g., gastrointestinal upset, excessive bruising, bleeding), and assess bleed risk. Frequency of follow-up thereafter is individualized based on clinical factors:4,29

- annually for those with normal renal function,

- every six months for those with eGFR 30-60 mL/min, and

- quarterly for those with eGFR < 30 mL/min.

At follow-up, confirm ongoing indication for DOAC use, review current medications for drug-drug interactions, assess patient’s relative risks of bleeding and/or thromboembolism, and address any adverse events. Periodically educate patients regarding the importance of medication adherence and early identification of adverse events, including signs of stroke and recurrent thrombosis.

Laboratory Testing

Poor renal function is a risk factor for bleeding and thus all patients on a DOAC should be tested at least once every 6-12 months.29,30 More frequent renal function testing may be indicated for certain patients (e.g., elderly patients with borderline renal function).29

Since all DOACs are partially metabolized by the liver31 and liver impairment can increase the risk of bleeding, liver function monitoring should be considered every 6-12 months for patients who have known hepatic dysfunction.26

Unlike warfarin, DOACs do not require routine laboratory monitoring of the anticoagulant effect. Classic coagulation tests like INR and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) are not helpful for assessing anticoagulant activity because results may be normal or abnormal, and prolongation of these clotting times do not reflect the degree of anticoagulant activity present.26 Consult a specialist if measuring the anticoagulant effect of a DOAC is being considered under special circumstances (e.g. after bariatric surgery). Refer to the Resources section below for information on the RACE line.

DOACs can interfere with special coagulation tests. Do not perform thrombophilia testing while a patient is taking a DOAC.

If special coagulation tests are being considered, contact a specialist. Refer to the Resources section below for information on the RACE line.

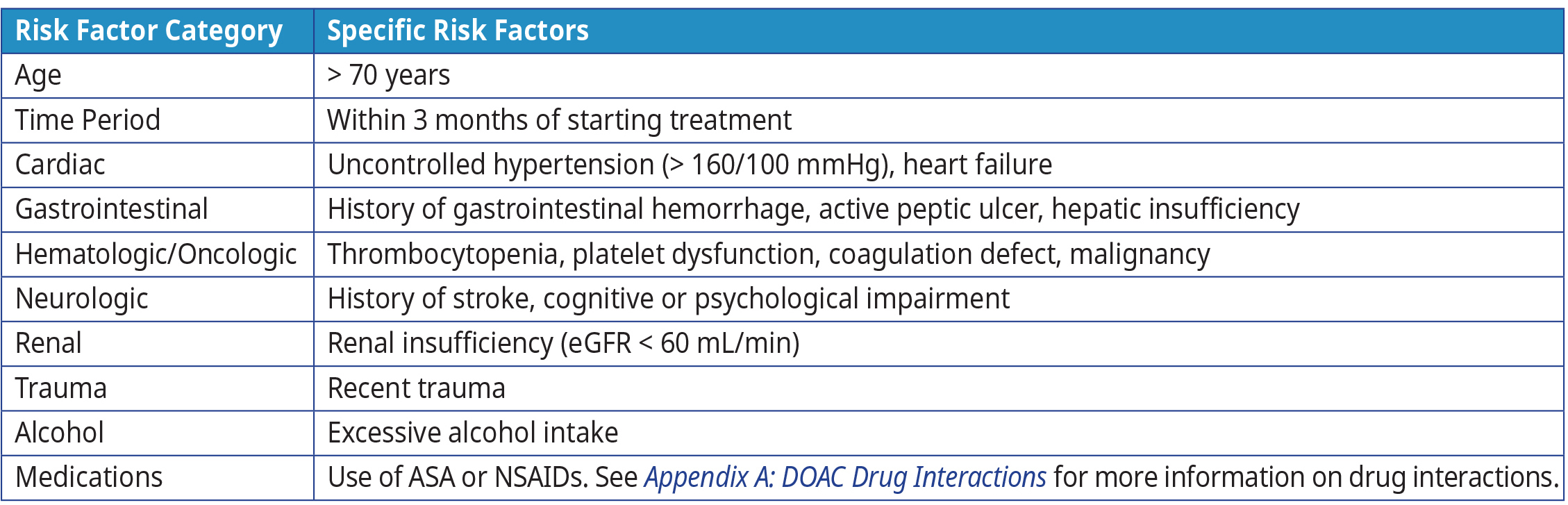

Bleeding Complications

Bleeding is a common adverse event for all anticoagulant drugs.32,33 The risk of bleeding is influenced by the concomitant use of certain medications, patient co-morbidities, and lifestyle. Refer to Table 3: Risk factors for bleeding complications on anticoagulation therapy or risk factors for bleeding complications on anticoagulation therapy.

Table 3: Risk for bleeding complications on anticoagulation therapy34-36

Abbreviations: ASA = acetylsalicylic acid; INR = international normalized ratio; mmHg = millimetres of mercury, mL = millilitre; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Abbreviations: ASA = acetylsalicylic acid; INR = international normalized ratio; mmHg = millimetres of mercury, mL = millilitre; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Adapted from: Warfarin Reversal Position Statement, Australasian Society of Thrombosis & Haematosis37

When a patient on a DOAC is bleeding, the decision to continue, temporarily interrupt or permanently stop the DOAC depends on the severity of the bleeding event, the likelihood the event can be stopped with minimal intervention, and the risk of recurrence. It is most important to determine and address the cause of bleeding while considering the patient’s individual risk-benefit profile with regards to risk of thrombosis with DOAC discontinuation versus risk to patient with ongoing bleeding. Specialist consultation is recommended if the risk of thrombosis is uncertain or if specialty involvement is required to mitigate bleeding (e.g., RACE consult line).

Overall, DOACs do not usually require reversal because of their short half-life.38 However, emergency reversal may be indicated for life-threatening bleeding situations or when urgent interventions are required.38 Dabigatran is currently the only DOAC with a dedicated reversal agent. Refer to BC Guidelines Oral Anticoagulants: Elective Interruption and Emergency Reversal, Canadian Cardiology Society NVAF guidelines, and Thrombosis Canada for more information on bleeding management. In general:

- For most minor bleeding events (e.g., minor lesions, simple tooth extraction) DOACs can be continued with the application of local measures. Prolonged pressure may be required.

- For moderate bleeding that is challenging to control, consider brief DOAC interruption (e.g.,1-2 days). Because DOACs have a short duration of action, prolonged interruption increases the risk of thrombosis substantially.

- For potentially life-threatening bleeding (e.g., severe GI bleeding, intracranial bleeding) or bleeding into a critical site (e.g., joint), the DOAC should be stopped immediately, and the patient should seek care at the closest emergency department.

References

- Gong IY, Kim RB. Importance of Pharmacokinetic Profile and Variability as Determinants of Dose and Response to Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, and Apixaban. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(7):S24-S33. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.04.002

- Scaglione F. New Oral Anticoagulants: Comparative Pharmacology with Vitamin K Antagonists. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013;52(2):69-82. doi:10.1007/s40262-012-0030-9

- Zhu J, Alexander GC, Nazarian S, Segal JB, Wu AW. Trends and Variation in Oral Anticoagulant Choice in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation, 2010-2017. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2018;38(9):907-920. doi:10.1002/phar.2158

- Andrade JG, Aguilar M, Atzema C, et al. The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(12):1847-1948. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2020.09.001

- López-López JA, Sterne JAC, Thom HHZ, et al. Oral anticoagulants for prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation: systematic review, network meta-analysis, and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. Published online November 28, 2017:j5058. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5058

- Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2093-2104. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1310907

- Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus Warfarin in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883-891. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009638

- Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, et al. Apixaban Versus Warfarin in Patients With Atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981-992. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107039

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139-1151. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905561

- Carnicelli AP, Hong H, Connolly SJ, et al. Direct Oral Anticoagulants Versus Warfarin in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Patient-Level Network Meta-Analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials With Interaction Testing by Age and Sex. Circulation. 2022;145(4):242-255. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056355

- Makam RCP, Hoaglin DC, McManus DD, et al. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants approved for cardiovascular indications: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pizzi C, ed. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0197583. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0197583

- Cohen AT, Bauersachs R. Rivaroxaban and the EINSTEIN clinical trial programme. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2019;30(3):85-95. doi:10.1097/MBC.0000000000000800

- Ortel TL, Neumann I, Ageno W, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv. 2020;4(19):4693-4738. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001830

- Gómez-Outes A, Terleira-Fernández AI, Lecumberri R, Suárez-Gea ML, Vargas-Castrillón E. Direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2014;134(4):774-782. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2014.06.020

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026

- Ebraheem M, Alzahrani I, Crowther M, Rochwerg B, Almakadi M. Extended DOAC therapy in patients with VTE and potential risk of recurrence: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(9):2308-2317. doi:10.1111/jth.14949

- Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Bosch J, et al. Rivaroxaban with or without Aspirin in Stable Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1319-1330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1709118

- Rivaroxaban (Xarelto). Thrombosis Canada; 2021. https://thrombosiscanada.ca/clinicalguides/#

- Bonaca MP, Bauersachs RM, Anand SS, et al. Rivaroxaban in Peripheral Artery Disease after Revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1994-2004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2000052

- Koutsoumpelis A, Argyriou C, Tasopoulou KM, Georgakarakos EI, Georgiadis GS. Novel Oral Anticoagulants in Peripheral Artery Disease: Current Evidence. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;24(38):4511-4515. doi:10.2174/1381612825666181226151959

- Seelig J, Pisters R, Hemels M, Huisman MV, ten Cate H, Alings M. When to withhold oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation – an overview of frequent clinical discussion topics. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2019;Volume 15:399-408. doi:10.2147/VHRM.S187656

- Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, et al. Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(13):1206-1214. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300615

- Woller SC, Stevens SM, Kaplan D, et al. Apixaban compared with warfarin to prevent thrombosis in thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome: a randomized trial. Blood Adv. 2022;6(6):1661-1670. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005808

- Covert K, Branam DL. Direct-acting oral anticoagulant use at extremes of body weight: Literature review and recommendations. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(11):865-876. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa059

- Chan YH, Chao TF, Lee HF, et al. Different Renal Function Equations and Dosing of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Atrial Fibrillation. JACC Asia. 2022;2(1):46-58. doi:10.1016/j.jacasi.2021.11.006

- Conway SE, Hwang AY, Ponte CD, Gums JG. Laboratory and Clinical Monitoring of Direct Acting Oral Anticoagulants: What Clinicians Need to Know. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2017;37(2):236-248. doi:10.1002/phar.1884

- Joosten LPT, Van Doorn S, Van De Ven PM, et al. Safety of Switching from a Vitamin K Antagonist to a Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulant in Frail Older Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Results of the FRAIL-AF Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation. Published online August 27, 2023:CIRCULATIONAHA.123.066485. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.066485

- Piran S, Robinson M, Kruja E, Schulman S. Reasons for Switching from Warfarin to a Direct Oral Anticoagulant: A Retrospective Study. Blood. 2018;132(Supplement 1):5060-5060. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-99-116974

- DOACs: Coagulation Testing. Thrombosis Canada; 2021. https://thrombosiscanada.ca/clinicalguides/#

- 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.011

- Elhosseiny S, Al Moussawi H, Chalhoub JM, Lafferty J, Deeb L. Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Cirrhotic Patients: Current Evidence and Clinical Observations. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;2019:4383269. doi:10.1155/2019/4383269

- Vazquez S, Rondina MT. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Vasc Med. 2015;20(6):3. doi:10.1177/1358863X15600256

- Gladstone DJ, Geerts WH, Douketis J, Ivers N, Healey JS, Leblanc K. How to Monitor Patients Receiving Direct Oral Anticoagulants for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation: A Practice Tool Endorsed by Thrombosis Canada, the Canadian Stroke Consortium, the Canadian Cardiovascular Pharmacists Network, and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(5):382-385. doi:10.7326/M15-0143

- Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. Pharmacology and Management of the Vitamin K Antagonists. Chest. 2008;133(6):160S-198S. doi:10.1378/chest.08-0670

- Schulman S, Beyth RJ, Kearon C, Levine M N. Hemorrhagic complications of anticoagulant and thrombolytic treatment. Am Coll Chest Physicians Evid-Based Clin Pract Guidel 8th Ed. 2008;133(6):257S-298S.

- Maddali S, Biring T, Kopecky S, et al. Health Care Guideline: Antithrombotic Therapy Supplement. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; 2013. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://vdocuments.site/health-care-guideline-antithrombotic-therapy-supplement-2013-05-30-health-care.html

- Baker RI, Coughlin PB, Gallus AS, Harper PL, Salem HH, Wood EM. Warfarin reversal: consensus guidelines, on behalf of the Australasian Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2004;181(9):6.

- Chan N, Sobieraj-Teague M, Eikelboom JW. Direct oral anticoagulants: evidence and unresolved issues. The Lancet. 2020;396(10264):1767-1776. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32439-9

Abbreviations

aPTT Activated partial thromboplastin clotting time

CBC Complete blood count

CrCl Creatinine clearance

DOAC Direct oral anticoagulant

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate

HIV Human immunodeficiency virus

LMWH Low molecular weight heparin

NVAF Non-valvular atrial fibrillation

VTE Venous thromboembolism

Resources

Clinical Decision Support Tools

- Child-Pugh Calculator

- Cockcroft-Gault Calculator

- PharmaCare Special Authority: Provides benefit status for medication coverage and specific medical circumstances of coverage, depending on BC PharmaCare plan rules.

- Thrombosis Canada periprocedural algorithm tool

Consultation Supports

- RACE: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program: RACE means timely telephone advice from specialist for Physicians, Medical Residents, Nurse Practitioners, Midwives, all in one phone call.

- Monday to Friday 0800 – 1700

- Online at www.raceapp.ca or though Apple or Android mobile device.

- Local Calls: 604–696–2131 | Toll Free: 1–877–696–2131

- For a complete list of current specialty services visit the Specialty Areas page.

- PathwaysBC: An online resource for current and accurate referral information for specialists and specialty clinics, including wait times and areas of expertise.

Related Guidelines

Additional Resources

- Health Data Coalition: An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist you in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing.

- General Practice Services Committee:

- Practice Support Program: Offers focused, accredited training sessions for BC physicians to help improve practice efficiency and support enhanced care.

- Chronic Disease Management and Complex Care Incentives: Compensates for the time and skill needed to work with patients with complex conditions or specific chronic diseases.

- QuitNow Smoking Cessation Program: Provides one-on-one coaching support and valuable resources in multiple languages. Phone: 1-877-455-2233 or Email: quitnow@bc.lung.ca

- Smokers’ Helpline: 1-866-366-3667

- Public Health Agency of Canada: Provides resources to help patients make wise choices about healthy living, including increasing physical activity and eating well.

- US Centre for Disease Control

- British Columbia Centre of Disease Control (BCCDC)

Appendices

- Appendix A: DOAC Drug Interactions (PDF, 1.3MB)

- Appendix B: Switching Between Anticoagulant Therapies (PDF, 95KB)

Associated Documents

- BC Pharmacare: Special Authority Request Form 5391 –Dabigatran for Atrial Fibrillation

- Contributors List (PDF, 163KB)

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, approved by the British Columbia Medical Association, and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

For more information about how BC Guidelines are developed, refer to the GPAC Handbook available at BCGuidelines.ca: GPAC Handbook.

THE GUIDELINES AND PROTOCOLS ADVISORY COMMITTEE

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact InformationGuidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee E-mail: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Web site: www.BCGuidelines.ca DisclaimerThe Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |

Keep current on BC Guidelines by signing up for our email notification service.

TOP

TOP