Wildfire Season Summary

The 2025 wildfire season, while impactful in nearly every region of B.C., was less destructive than the previous two seasons. Despite fewer starts than average (1,370 total), the 886,300 hectares burned in 2025 is well above B.C.'s 10-year average.

On this page:

Summary

While spring activity was concentrated in the northeastern region of the province with some overwintering fires paired with clusters of new detections, favourable weather conditions contributed to a decrease in mid-summer activity provincially. Despite widespread precipitation in mid-August, the end of the month and early September saw another surge in wildfire activity, particularly in the southern and central regions.

This late-season escalation driven by above-seasonal temperatures, lightning activity and regionally severe underlying drought conditions demonstrated that the traditional “core wildfire season” is a thing of the past. With its ups and downs, the 2025 wildfire response season showed us the importance of readiness, shared action and strong relationships built on trust.

Moving into the winter, the BC Wildfire Service continues to work with its partners in all quarters to advance the important work of preparedness, prevention and recovery. Wildfire touches lives in every part of B.C., from the most northeasterly corner of the province to the Rocky Mountains, to Vancouver Island, and everywhere in between. The BC Wildfire Service remains committed to ongoing and respectful collaboration in this critical work with valued partners in all regions of B.C.

Preparedness

Training and recruitment

In 2025, the BC Wildfire Service’s expanded wildland-firefighter hiring window resulted in more than 2,200 applicants, a new record. Essential training was offered earlier than in past seasons to ensure staff were prepared to meet increasingly challenging early season conditions. New Recruit Boot Camps began in April, with three additional First Nations Boot Camps offered to increase Indigenous recruitment and retention.

BC Wildfire Service continues to build on the partnership with Thompson Rivers University (TRU). In September of this year, TRU launched its inaugural courses in the Wildfire Communications and Media Certificate, marking the first year of a new academic partnership with the BC Wildfire Service. While this collaboration has been ongoing for many years, this is the first time formal wildfire-focused academic programming is being offered at TRU.

Collaborative response

Twenty-five communities were supported by their regional districts to pursue training and the purchase of personal protective equipment through the FireSmart Pilot Program for Regional District Cooperative Community Wildfire Response Organizations. Funding for these activities will be managed through the FireSmart Community Funding and Supports program in future. Through a collaboration with Natural Resources Canada and Thompson Rivers University, an additional funding stream for rural, remote and Indigenous community training was also rolled out in 2025.

BC Wildfire Service worked with partners to build on existing tools like the Collaborative Partnership Guide, designed to assist all wildfire emergency response partners. This guide outlines the roles and responsibilities of different groups involved in wildfire response and is a tool for collaboration before, during and after wildfire events. New for 2025, the guide now includes a chapter specific to Indigenous governments, which will continue to evolve based on feedback from partners.

This year there were eight Indigenous Initial Response crews working across the province. Indigenous Initial Response is one pathway for collaboration that enables First Nations to support wildfire response on their traditional territory. These three or four-person crews are fully integrated into wildfire response and can be deployed to support initial attack within an agreed-upon service area within their traditional territory.

Throughout 2025, BC Wildfire Service continued to improve communications with partners during wildfire response through further implementation of the Liaison Program, which pairs staff working in the Liaison Officer position with representatives from communities, industry and other partners to ensure effective two-way information flow. This program has been a focus since 2023, and the roles, responsibilities, training and certification pathways for staff and partners who function as Liaisons and representatives of partner agencies will continue to be refined.

Tools and technologies

Last year, two helicopters helped fight wildfires at night, working in tandem doing detection, reconnaissance, tanking and supporting ground crews. In 2025, the BC Wildfire Service doubled the size of the fleet to four helicopters and trained more Night Vision Imaging Systems (NVIS) Flight Officers to safely support night operations and expanded their terms to ensure coverage as we continue to see prolonged wildfire response seasons. They completed 260 missions provincially. They were utilized for wildfire detection, reconnaissance and water delivery.

After successfully piloting enhanced wildfire predictive technology during the 2024 wildfire season, the BC Wildfire Service secured a long-term contract to provide industry-leading wildfire decision support tools and expertise for 2025. These decision support tools help us to analyze vast amounts of data to make evidence-based decisions across prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. BC Wildfire Service continues to train and build capacity around new predictive technologies, ensuring staff have the knowledge and experience needed to translate the outputs of these technologies into sound operational decision making.

In addition to enhanced predictive technologies, improvements to provincial weather stations made during 2024 have allowed the BC Wildfire Service to expand weather prediction capabilities to provide staff with the best data available to inform operational decision making. This spring also saw advancements in the development of a province-wide wildfire camera network with AI-assisted smoke detection to enhance situational awareness, improve operational response and provide data for wildfire research. This summer, the joint research project with UBC Okanagan coordinated with communities, local government, First Nations and industry to identify potential new locations for camera monitoring around B.C.

Prevention

As part of the 2025 Provincial budget, $40 million was allocated to BC Wildfire Service to support programs that support resiliency, including wildfire risk reduction projects, cultural and prescribed fire, FireSmart initiatives, and more.

Thanks to ongoing investment in prevention and mitigation activities, BC Wildfire Service was able to work with partners in government, First Nations, industry, and the non-profit sector to reduce the negative impacts of wildfire by focusing on wildland and community resiliency, contributing to policy and research development, enhancing forest health, and promoting FireSmart as a shared responsibility.

Crown Land Wildfire Risk Reduction

Nearly 200 wildfire risk reduction projects were completed in 2024/25, treating approximately 2,440 hectares of land, including 16 prescribed burns covering an additional 790 hectares. Another 200 projects are planned or still underway for 2025/26.

Wildfire risk reduction involves removing flammable vegetation and woody debris to reduce the amount of fuel available to a wildfire. Depending upon local conditions such as forest type and topography, fuel management projects may be completed by hand, with heavy machinery, prescribed fire, or a combination of all three. This helps reduce wildfire intensity and provides firefighters with more options and a safer environment in which to carry out suppression activities when wildfire threatens a community.

FireSmart BC

To date, 280 communities across B.C. have received FireSmart funding, including 132 First Nations and 148 local governments.

FireSmart funding supports projects in communities, such as planning and education programs that focus on raising public awareness of how wildfires can impact communities and what steps individuals can take to mitigate that risk.

This includes grants for 189 active FireSmart Coordinators delivering FireSmart programming and 113 participating partner agencies that deliver professional home assessments that identify how people can reduce the chance that a wildfire will damage or destroy their home. Over 8,650 home assessments have been completed, with almost 1,900 in 2025 alone.

In April 2025, FireSmart BC successfully hosted another sold-out (800+ attendees) Wildfire Resiliency and Training Summit in Penticton, B.C., which focused on bringing safe and planned fire back to the landscape and strengthening relationships. The five-day summit brought together firefighters, community leaders, industry professionals, and experts to cross-train and discuss innovative approaches to wildfire management and community resilience.

FireSmart B.C.’s 2025 campaign was also highly successful, with a 157 per cent increase in website traffic and a 276 per cent increase in new users. As of 2025, 60 per cent of communities in B.C. have developed a Community Wildfire Resiliency Plan, and 90 per cent of residents familiar with FireSmart think there are things they can do to protect their home.

The BC Wildfire Services continues to advance the safe and intentional use of cultural and prescribed fire across B.C. Through partnerships, training and on-the-ground delivery, the organization supported fire as both an ecological and cultural practice, recognizing its role in maintaining resilient landscapes and community safety. This work reflects the province’s commitment to collaborating with Indigenous peoples, local governments and partners to build healthy relationships with fire, using it in ways that are safe, respectful and sustainable.

Across the province, 111 cultural and prescribed fire projects were planned for the 2025 season, representing 15,914 hectares of proposed treatment area. By October, 69 projects had been completed, successfully treating about 4,756 hectares. The Prince George Fire Centre led in total hectares treated, completing 14 projects covering more than 3,393 hectares, followed by strong activity in the Southeast, Kamloops and Cariboo fire centres. These results demonstrate continued progress in expanding the scale and effectiveness of cultural and prescribed fire across the province.

The BC Wildfire Service continued to invest in training and knowledge exchange through the second Kootenay ʔa·kinq̓uku TREX (Prescribed Fire Training Exchange) offering and ongoing work to expand this method of training and capacity building.

Response

Fuel and weather conditions

Significant fire activity first emerged in the Prince George Fire Centre in B.C.’s northeast where the impacts of significant burnt areas, overwintering fires and underlying drought combined to create challenging conditions in April and May. The unseasonably dry fuels and persistent winds supported rapid spread on several new and existing wildfires, triggering short-term evacuation orders and alerts. Of the 886,300 hectares burned in 2025, 724,000 occurred in the Prince George Fire Centre alone – more than 80 per cent.

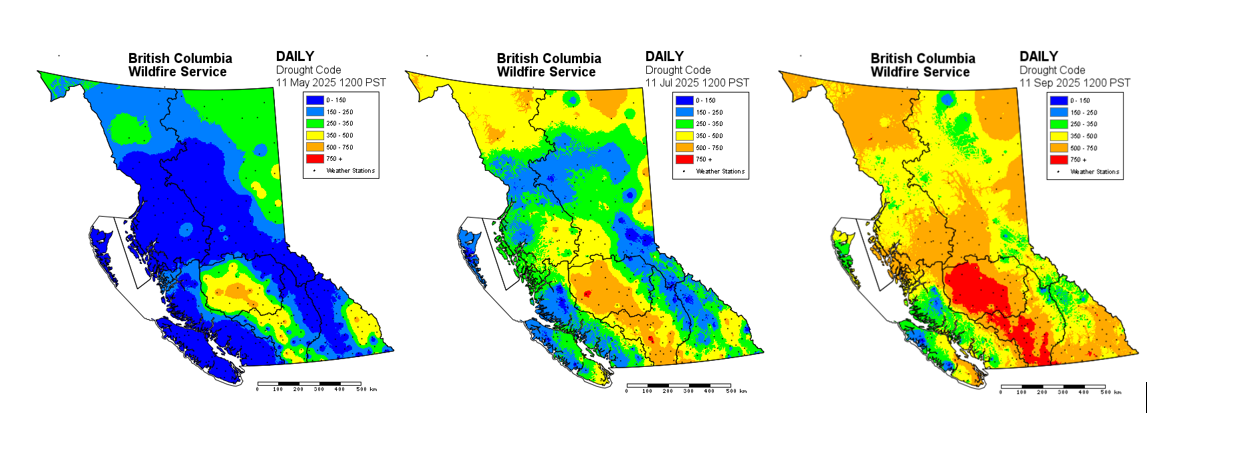

These maps indicate Drought Code values for the entire province in May, June and September 2025.

While drier-than-normal conditions in the Peace and Fort Nelson regions drove significant activity in the northeast, the Coast and parts of the Interior experienced wetter-than-normal conditions throughout the spring. These cooler, wetter conditions impacted much of the province through the tail end of June and into July depressing activity levels in most of the province during what is considered the historical “core” fire season. While B.C. continued to see less intense fire activity through July and early August than was observed in recent years across the southern half of the province, there were notable exceptions on Vancouver Island where severe drought and difficult terrain created challenging response conditions.

At the end of August, a late-season heatwave lasting into early September dried out forests and fuels creating the ideal conditions for new wildfire starts. Throughout that 14-day period, 115 daily maximum temperature records were broken across the province. During this prolonged heat, a multi-day dry lightning event resulted in 5,925 lightning strikes and 88 new fires across central and southern B.C. between August 28 and 31.

This heat wave converged with a lack of precipitation and the aftermath of the pine beetle epidemic in the West Chilcotin where this period saw some of the most aggressive fire behaviour observed during the 2025 wildfire response season.

Cumulative impacts

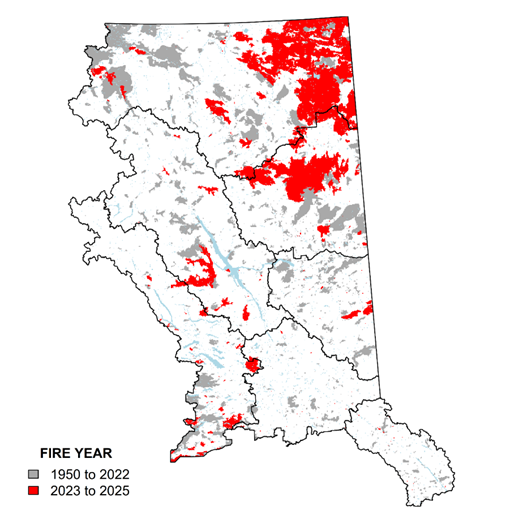

From 2023 to 2025, a vast amount of area has burned in northeastern B.C.

In the Prince George Fire Centre, the area burned over the past three years is equivalent to the area burned over the preceding 72 years from the beginning of recorded fire history in 1950 to 2022. In the Fort Nelson and Fort St. John fire zones alone, 23 per cent of the vegetated land base burned in these three years.

Area burned across the Prince George Fire Centre, with area burned in the past three fire years (2023-2025) depicted in red and area burned between 1950 and 2022 in grey.

In addition to responding to wildfires in the northeast this fire season, BC Wildfire Service has been working to understand the scope and scale of this disturbance and what it means for future fire seasons and the landscape.

Multi-year drought and overwintering wildfires that burn deep into the ground have combined to destabilize tree stands. Wind moving through these stands has resulted in significant blowdowns – large accumulations of downed trees on the forest floor – which can intensify fire behaviour and challenge wildfire response. The BC Wildfire Service has been using remote sensing to spatially map and quantify this blowdown in the northeast to understand the potential mid and long-term impacts.

Work has been ongoing to understand fuel moisture conditions in the northeast and what level of precipitation would be needed to reduce deep, persistent drought conditions. Moisture sampling field work was completed in Dawson Creek, Fort St. John and Fort Nelson fire zones to confirm fuel moisture values and determine whether summer rains impacted these values.

Without significant precipitation to alleviate drought conditions, overwintering wildfires will continue to be a challenge for the northeast.

BC Wildfire Service has been studying how these significant impacts to the landbase will influence fire behaviour in the years ahead. For example, in some areas where recent fires have left large breaks between forested areas, new fires may burn less intensely or move more slowly through the landscape. At the same time, ongoing drought, blowdown and the repeated impacts to growing season have set forest succession back in the northeast.

Understanding these cumulative impacts in the northeast has been and will be essential to take effective action ahead of next season and into the future. With the scope, scale and impacts to the landscape and communities, the reality is that one fire management agency alone cannot confront this challenge. A whole-of-society approach and adaptive management approaches will be needed, involving communities, First Nations, land managers, industry and many others.

Significant incidents

Since April 1, 2025, more than 1,350 wildfires resulted in an estimated 886,360 hectares of land burned. While any incident that affects people or communities is impactful, some larger wildfire incidents are particularly significant. The following table lists the notable wildfires of 2025, but crucially, this information does not capture the many interface wildfires that were actionable by initial attack crews before they could have an impact. In 2025, 85% of all wildfires were contained under four hectares.

This table is filterable by any heading.

| Fire Name (Number) | Fire Centre | Suspected Cause | Size (ha) | Discovery Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pocket Knife Creek (G80352) | Prince George | Lightning | 149,505 | May 19 |

| Summit Lake (G90413) | Prince George | Humans | 80,842 | May 28 |

| Kiskatinaw River (G70422) | Prince George | Lightning | 26,195 | May 28 |

| Glacier Creek (R90700) | Northwest | Lightning | 2,037 | June 20 |

| Izman Creek (K70783) | Kamloops | Humans | 243 | July 1 |

| Placer Creek (K60922) | Kamloops | Humans | 3,135 | July 12 |

| Cantilever Bar (K71095) | Kamloops | Humans | 1,472 | July 28 |

| Bear Creek (V11110) | Coastal | Humans | 224 | July 29 |

| Wesley Ridge (V71145) | Coastal | Humans | 588 | July 31 |

| Mount Underwood (V71498) | Coastal | Under Investigation | 3,518 | Aug 11 |

| Beef Trail Creek (C51672) | Cariboo | Lightning | 13,993 | Aug 27 |

| Itcha Lake (C11659) | Cariboo | Lightning | 57,885 | Aug 27 |

| Smokey Lake (C51730) | Cariboo | Lightning | 7,790 | Aug 29 |

| Klina Klini (C51843) | Cariboo | Lightning | 541 | Aug 29 |

| Redbrush* (C51874) | Cariboo | Lightning | 5,412 | Sept 1 |

Important wildfire information was shared regularly through official BC Wildfire Service social media channels, on the BC Wildfire Service web and mobile app and as operational update videos on YouTube.

Resources

This year, the BC Wildfire Service entered the response season with approximately 1,300 firefighters, 600 permanent support staff and 300 seasonal support staff. In addition to BC Wildfire Service Type 1 firefighting crews, there were approximately 1,200 contract personnel, including crew members, danger tree assessors and fallers, and others prepared to respond.

Five BC Wildfire Service Incident Management Teams (IMTs) were deployed to major incidents or wildfire complexes across the province to help relieve fire centres and zones in areas of concentrated fire activity. In total, these teams were deployed 27 times. These teams rotated in two-week increments, tirelessly working alongside other emergency and land management personnel including local governments, First Nations and community representatives to achieve containment objectives.

Nationally, Canada faced its second worst season in history in terms of area burned, with more than 8 million hectares nationwide. It was an honour to be able to support partners in other jurisdictions as much as possible, as they have come to B.C.’s aid in the past.

In January, BC Wildfire Service supported California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) and the U.S. Forest Service in response to multiple fires in California, including the Palisades, Eaton and Hughes fires.

Beginning January 11, BC Wildfire Service personnel were embedded with CAL FIRE’s Incident Management Team at a fire camp in Malibu, near Los Angeles. On January 13, an additional 22 Type 1 firefighting crews and an agency representative were deployed to work with the U.S. Forest Service in the Los Angeles area. Most personnel returned home by January 23, having contributed both management expertise and frontline firefighting capacity as part of the ongoing commitment to mutual aid and international wildfire response.

Although British Columbia experienced a lighter wildfire season than in recent years, other provinces and territories faced unprecedented fire activity. In response, BC Wildfire Service deployed personnel and equipment across the country, supporting Yukon, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and— for the first time—Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia. This year, the BC Wildfire Service deployed to more out of province locations than any season prior. Over the course of the season, B.C. sought assistance from New Brunswick, Alberta, Ontario, Yukon and the Canadian Forest Service. Support was also sent to and received from various state agencies in the United States of America.

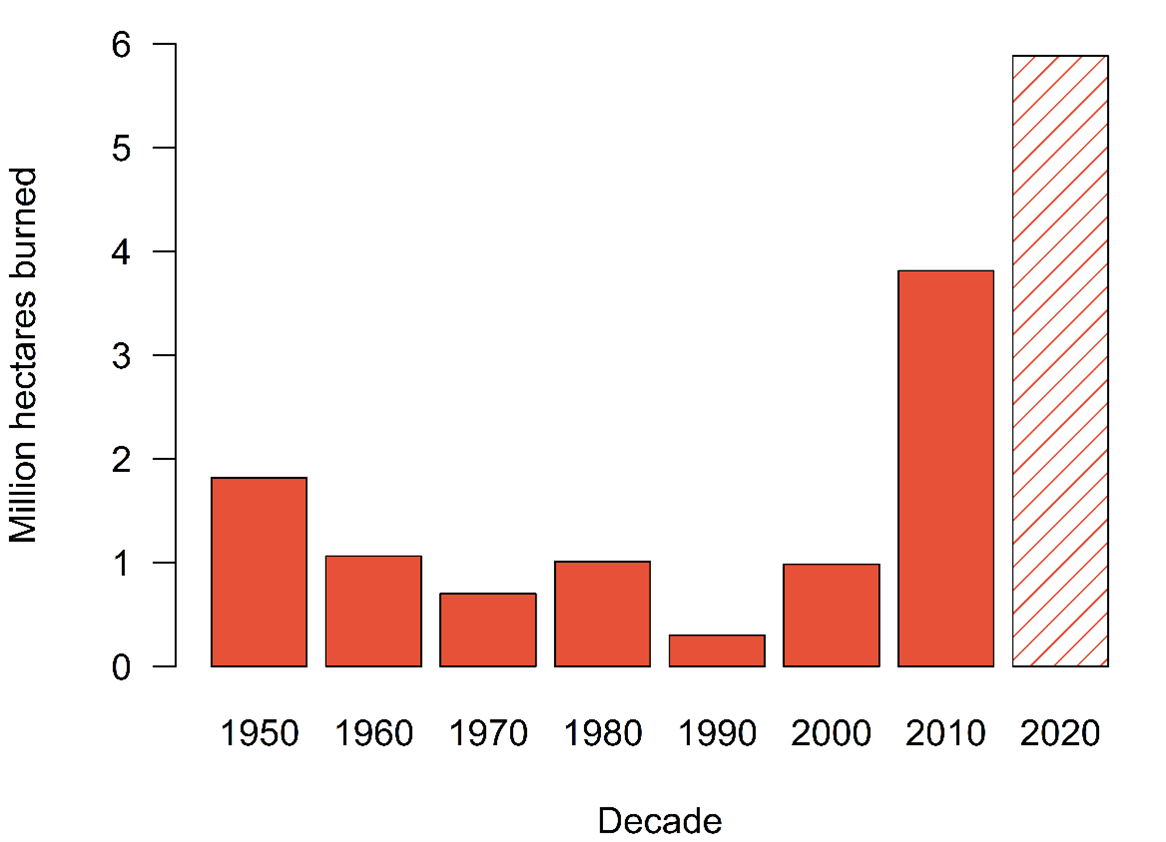

Despite seeing fewer hectares burned in B.C. in 2025 than in 2024 or 2023 and less need for out-of-province resource support, it’s important to consider the bigger picture and longer-term trends. This bar chart shows the hectares burned per decade for the past 85 years, demonstrating how climate change is accelerating the scale of wildfire impacts on the land base. Note that the 2020s bar shows area burned for the five-year period from 2020 to 2025 and will continue to grow throughout the remainder of the decade. This rapidly increasing occurrence of large wildfires in a changing climate underscores the need for an all-of-society approach to wildfire response and strong partnerships across borders.

In August, fire chiefs David Scheurich and Mark Pimentel from CAL FIRE travelled to B.C. as part of the ongoing partnership. Over the course of a week, they met with staff, toured facilities and observed operations in Kamloops and visited the Cantilever Bar wildfire camp. The visit provided a valuable opportunity to compare organizational structures, equipment, tactics and logistics, and to identify considerations for potentially bringing additional CAL FIRE personnel to B.C. in the future. While fire activity was limited during their stay, the exercise successfully tested systems and highlighted areas for collaboration. This long-standing partnership continues to strengthen interagency trust, build mutual capacity and support shared learning as both jurisdictions face evolving wildfire challenges.

In 2025, BC Wildfire Service continued to see positive growth in the evolution of collaboration with local fire services. Through the interagency agreement, 69 fire departments supported wildfire response efforts this year resulting in 56 deployments of structure protection units and 58 deployments of structure protection crews. Seventy-six fire engines from local departments were deployed alongside these structure protection units and crews.

The strength of these partnerships is particularly crucial when wildfires impact interface areas, as evidenced by the Wesley Ridge wildfire on Vancouver Island, where cooperation with local fire services and access to their resources supported seamless structure protection and defense operations that protected all dwellings in the Little Qualicum River Village.

Eight airtanker groups were stationed throughout the province this season. At the height of the 2025 fire season there were 27 airtanker and birddog aircraft engaged in response operations. This year, airtankers flew a total of 364 missions, including 55 practice runs. This total is below the 10-year average of 463 missions per year. More than 10.3 million litres of retardant and 12.9 million litres of suppressant were dropped over the course of the 2025 response season.

In 2025, longer-term contracts guaranteed the availability of heavy lift helicopters in the core season. The most helicopters deployed to response on a single day this year was 108 on September 6. This season the helicopter fleet flew for more than 29,442 hours, actioning 1,365 fires.

Skilled heavy equipment operators with local knowledge were once again a critical resource for wildfire operations. At peak response, there were hundreds of heavy equipment personnel engaged in response and rehabilitation activities across the province. For the 2025 response season, BC Wildfire Service trialed a heavy equipment task force concept. These teams consisted of four pieces of heavy equipment, an equipment boss and two-line locators to quickly deploy to rapidly evolving incidents. BC Wildfire Service continues to engage with heavy equipment operators to build on the success of this trial.

Recovery

Fire is a natural, important part of many ecosystems in B.C., but high-intensity wildfires and related suppression activities can leave the landscape in need of recovery and rehabilitation. Wildfire recovery includes wildfire suppression rehabilitation, post-wildfire natural hazard risk analysis and ecological wildfire recovery.

During response operations this season, over 1,900 kilometres of control lines and access trails were established. To rehabilitate these landscapes, over 30 rehabilitation specialists were deployed to active wildfires across all six regional fire centres. Of the more than 1,350 fires that began during the 2025 season, 100 require rehabilitation assessment and/or treatment. Rehabilitation work begins during response and is ongoing, as weather permits.

The work of assessing natural hazard risk on wildfires that began this year is ongoing. So far 96 wildfires have been screened for geohazard risk, with field work and reporting continuing into the fall.

Approximately 20 ecological wildfire recovery projects are ongoing, ranging from recovery planning to projects focused on invasive species, hydrology and eco cultural values.

This season, BC Wildfire Service made headway developing a Rapid Ecological Assessment Process, wherein a team of natural resource specialists assess ecological, hydrological, cultural and other impacts caused by wildfire. This is a new process for the BC Wildfire Service and is designed to aid land management decisions and land-based recovery post-wildfire. The first field team was deployed to test this process on the Mt. Underwood (V71498) wildfire in September 2025.

Provincial Statistics

- For year-to-date statistics and historical comparisons, visit the Dashboard of the BC Wildfire Service app.

- Approximately 55 per cent of wildfires were caused by lightning this year; however, these starts account for 87 per cent of the total area burned this year. Approximately 43 per cent were attributed to human activity. A small percentage remain undetermined or under investigation.

- This wildfire season approximately 30 communities were impacted by evacuation orders and alerts, with a total of approximately 2,670 evacuees

- BC Wildfire Service fielded over 22,079 calls to report wildfires this season. In addition, approximately 1,384 wildfire reports were submitted through the BC Wildfire Service app’s ‘Report a Fire’ function.

- BC Wildfire Service took 26,926 calls specifically related to open burning.

- Eighty-two per cent of the total hectares burned in 2025 were within the Prince George Fire Centre.

- As of November 1, the estimated cost of wildfire suppression was $510 million.

Looking Ahead

Research and Innovation

Reflecting on the response season, it is crucial to continue to look ahead and explore new technologies, approaches and research opportunities to build a safer, more resilient B.C. Through a range of research partnerships and a commitment to innovation, BC Wildfire Service is working toward actionable learning to make a tangible difference to how this important work gets done. BC Wildfire Service continues to focus on the health, wellness and safety of wildland firefighters, as well as the natural science related to wildland fire behaviour.

Some areas of focus for 2025 included:

- Multi-year research into the cardiorespiratory health impacts of wildfire smoke, ash and dust to wildland firefighters and identifying mitigation strategies

- Evaluating advancements in automated wildfire risk and fire growth modelling software to enhance wildfire planning and response

- Studying the best ways to create FireSmart structures and communities, and increasing the efficacy of fuel treatments to build resilience

Outlook

You can check out the 2025 Fall Seasonal Outlook here for a summary of the weather and fire behaviour B.C. experienced this year. Mixed conditions combined with persistent drought in some parts of the province contributed to another significant wildfire season with fewer individual fires than average, but above-average area burned.

With the lingering impacts of the late-season heat wave combined with above-average temperatures in early October, warmer and drier-than-normal conditions are expected to persist into the fall and winter.

Reflections

Reflecting back on the 2025 response season, the BC Wildfire Service is grateful to everyone who played a part in keeping people in B.C. safe.

Fire is a reality of the landscape in British Columbia. The BC Wildfire Service will continue to build on the lessons learned and experienced gained in 2025 and past seasons. Everyone has a role in building a more resilient B.C., and the BC Wildfire Service remains committed to working across all four phases of emergency response to support healthy communities, landscapes and relationships with fire.

To learn more about how we operate across all four phases of emergency management, please explore the rest of this site.

Prevention

Reduce the negative impacts of wildfire on public safety, property, the environment and the economy using the seven disciplines of the FireSmart program. Learn about funding available for communities and actions you can take on your property on our wildfire prevention funding webpage.

Preparedness

Preparing for a wildfire event increases the resiliency of our homes and communities. Access valuable resources to prepare your family for an emergency by reading the wildfire preparedness guide.

Response

The BC Wildfire Service detects, monitors and responds to an average of 1,600 wildfires per year. Learn more about wildland firefighting on our wildfire response webpage.

Recovery

Wildfire recovery considers the social, economic and environmental impacts a wildfire may have on an area. Get more information about community supports after a wildfire event on our wildfire recovery resources webpage or Prepared BC's recovering after a wildfire webpage.

Work with us

The BC Wildfire Service has a number of seasonal positions open for application across the province, including crew members, dispatchers, asset management assistants and more! If you are interested in fast-paced, meaningful and exciting work, we have employment for you! Take a look at our Seasonal Job Opportunities webpage to learn what positions are available! Be sure to check back regularly for new opportunities.

Tapes of 2024

Play, pause, fast forward and rewind the season on our YouTube channel.

Previous Wildfire Season Summaries

2024 Wildfire Season Summary

Following B.C.'s worst wildfire season on record, the BC Wildfire Service and its partners began preparing for the 2024 wildfire season by strengthening planning, prevention, and preparedness as well as response and recovery efforts throughout the province. Although fire activity was not as widespread as in 2023, it was still an impactful season.

Preparedness

Building on the lessons learned from the 2023 wildfire season, the BC Wildfire Service participated in the Premier’s Expert Task Force on Emergencies. After months of engagement and information gathering, the task force made several recommendations for enhancing resources, partnerships and technologies in wildfire and emergency management

Collaborative Response

The growing impact of climate change is creating more demand for greater wildfire mitigation and management strategies in rural and remote communities. Building on the recommendations of the expert task force, the BC Wildfire Service began working in partnership with local community members who have basic wildfire suppression training and are interested in supporting response efforts around their communities. Strengthening local involvement in wildfire response empowers communities by creating opportunities to support fire departments and other agencies during a wildfire.

Responding to emergencies is a collaborative effort involving more than one agency. The Collaborative Partnership Guide was developed ahead of the 2024 wildfire season to assist all wildfire emergency response partners. This guide outlines the roles and responsibilities of different groups involved in wildfire response and is a tool for collaboration during a wildfire.

Training and recruitment

Ahead of the 2024 wildfire season, a series of enhancements were made to the wildland firefighter recruitment strategy to improve the application process for rural and remote communities. This work involved expanding First Nations bootcamps, extending the hiring period for new recruits and encouraging applicants to indicate desired work locations.

In addition, a first-of-its-kind in North America wildfire training and education centre was announced in partnership with Thompson Rivers University (TRU). The program will offer comprehensive wildfire training and education, progressing from basic field skills to academic diploma and degree programs in wildfire and emergency management disciplines. This dedicated wildfire program will offer career development pathways in wildfire management for B.C.’s future wildland firefighters.

Building on experiences from the 2023 wildfire season, the annual Wildfire Resiliency and Training Summit was held in Prince George this spring. This five-day event brought together over 760 participants representing over 80 departments and agencies from B.C. and beyond. Through a combination of presentations, workshops and fieldwork, participants explored how to better prepare for the upcoming season by strengthening wildfire resiliency within our communities and forests. The 2024 Wildfire Resiliency and Training Summit saw a 66 per cent increase in individual First Nations attendees and a 63 per cent increase in the number of First Nation communities represented.

The BC Wildfire Service remains committed to building capacity and training by strengthening local knowledge within the organization and furthering career opportunities within wildfire management.

Tools and technologies

In collaboration with the Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness, the BC Wildfire Service highlighted new and improved preparedness tools ahead of the 2024 wildfire season to help people plan and stay informed. This includes the redevelopment of the BC Wildfire mobile and web application, which provide users with timely and accurate information on wildfires across the province. Significant updates and features were rolled out in 2024, including a dashboard which provides users with a summary of current activity and access to various wildfire statistics. Comprehensive instructional materials were also released to assist users with this valuable tool.

After exploring and successfully trialing alternative fire behaviour analysis technology, the BC Wildfire Service adopted new predictive software, which enhances wildfire predictions by augmenting data from weather models, topography and fuel maps using real-time observations input directly from the field. While wildfire predictive technology does not replace the experience and skills of qualified wildfire staff, it provides decision-makers with more intelligence to plan and conduct effective wildfire response. Collaborative efforts with jurisdictions using similar technologies, including California and Australia, have allowed the BC Wildfire Service to quickly operationalize and expand the use of these tools.

The BC Wildfire Service began exploring the use of Night Vision Imaging Systems (NVIS) in 2019 on rotary wing aircraft to perform reconnaissance missions at night. After carefully conducting numerous successful trials, the BC Wildfire Service integrated NVIS into its wildfire response operations ahead of the 2024 wildfire season. Several BC Wildfire Service staff were trained and rostered as NVIS observers to accompany certified NVIS pilots on reconnaissance, detection and mapping missions. At least a dozen air carriers contracted for the 2024 wildfire season have NVIS capabilities. Over time, more BC Wildfire Service staff will be trained in NVIS to build our capacity with this technology.

The BC Wildfire Service is committed to continuously improving our operations while employing our most trusted tools and technology to safely and effectively manage wildfires in B.C.

Prevention

The BC Wildfire Service has grown into a year-round organization focused on proactively reducing wildfire risks in addition to wildfire response. Prevention initiatives ahead of the 2024 wildfire season consisted of increased funding, planning and implementation of community resiliency and wildfire risk reduction projects, contributions to policy and research development and ongoing strategic partnership with First Nations, local governments and municipal fire departments.

As part of the 2024 provincial budget announced this February, $40 million was allocated to the BC Wildfire Service Prevention program, which includes Crown Land Wildfire Risk Reduction (CLWRR), the Cultural and Prescribed Fire program, FireSmart and other wildfire resiliency partnerships. An additional $30 million was dedicated to the FireSmart Community Funding and Supports program (FCFS), which funds community-based FireSmart initiatives undertaken by local governments and First Nations. The Forest Enhancement Society of BC (FESBC) also received $60 million in funding from the Provincial Government’s Budget 2024, with $20 million to be allocated each year over the next three years. The primary goal of these projects is wildfire risk reduction and/or enhanced wood fibre utilization while also achieving additional benefits such as enhancing wildlife habitat, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, improving recreational opportunities and rehabilitating forests.

Crown Land Wildfire Risk Reduction

The Crown Land Wildfire Risk Reduction (CLWRR) program helps build and maintain wildfire resilient landscapes and communities across the province through tactical planning and application of fuel management projects within the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI).

Since 2019, this program has invested approximately $80 million in CLWRR projects, treating 11,246 hectares of land to date. While 2024 projects are still underway, program highlights from this year include:

- $22.4 million in CLWRR activities, including Cultural and Prescribed fire, implemented across the province

- 3,906 hectares of CLWRR treatments completed to date

- 11 CLWRR plans finalized for future treatments

Cultural and Prescribed Fire

The BC Wildfire Service is committed to helping restore the use of fire for both ecological and cultural prosperity by strengthening local partnerships, removing barriers and expanding capacity.

In collaboration with First Nations partners, the use of cultural and prescribed fire will continue to be expanded both as an important Indigenous practice and as a tool for land stewardship and wildfire mitigation. After formal consultation throughout 2023 with First Nations, and engagement sessions facilitated by the First Nations Forestry Council (FNFC), the Province made amendments to the Wildfire Act and Regulation to remove barriers to Indigenous uses of fire. These amendments create new opportunities for partnerships between the BC Wildfire Service and First Nations to carry out cultural and prescribed fire initiatives.

Of the 60 cultural and prescribed fire projects planned for 2024, 48 were implemented, treating a total of 3,412 hectares. Thirty-six were carried out in the spring and 12 were completed this fall. There are 88 burning projects planned for 2025, and more projects being actively developed and reviewed to be implemented in the years ahead.

The BC Wildfire Service and First Nations’ Emergency Services Society (FNESS) began planning in 2023 for a prescribed fire training exchange (TREX) to be conducted in the southeast region of the province. The Southeast Fire Centre worked with their local partners including Ktunaxa Nation communities (ʔaq̓am, Yaqan nuʔkiy), Osoyoos Indian Band, Selkirk and Rocky Mountain Resource Districts, City of Cranbrook, Regional District of East Kootenay as well as the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship (WLRS) to identify prescribed fire projects in the region. In early 2024, ʔaq̓am offered to co-host this training and welcome participants into their community. The first delivery of TREX in B.C. was piloted this September over the course of two weeks, gathering 33 participants and 12 facilitators representing 13 different agencies and communities. The success of this training encourages our shift towards more collaborative wildland stewardship and serves as a model for future TREX offerings in other regions of the province. Read the final report to learn more and check out the video to see participants burning and learning together.

FireSmart BC

FireSmart BC continues to be a leader in facilitating community participation in wildfire resiliency, providing financial support through the FireSmart Community Funding and Supports (FCFS) program and go-to resources for individuals and communities. From Budget 2022 and 2023, $100 million was allocated to the FCFS program.

In 2024, FireSmart BC and BC Wildfire Service’s prevention program worked with the Union of BC Municipalities (UBCM) to prioritize improving the accessibility of their initiatives by streamlining administrative requirements and offering better long-term certainty for communities applying for prevention funding. Approximately $27.5 million was allocated to FCFS this year and has funded communities across B.C. to engage in FireSmart activities through staffing, education, community development, emergency planning and fuel management projects. To date, 265 communities have received FCFS, including 117 First Nations and 148 local governments.

FireSmart BC offered communities directly affected by the 2023 wildfire season a one-time recovery uplift of up to $100,000. This funding, for example, could be put towards clearing post-wildfire debris and other efforts to help communities rebuild. Six local governments affected by the 2023 wildfire season participated in this program in 2024; and this program will be offered again in 2025.

Response

Overwintering fires

The beginning of the 2024 fire season was heavily influenced by compounding, unprecedented drought conditions, allowing for some wildfires from the season prior to burn deep underground and persist overwinter. This spring, around 80 overwintering fires from the 2023 fire season remained active in northeastern B.C. Although overwinter fires are not a new phenomenon, and many were burning at a low intensity and in remote locations, the amount of active fire present on the landscape at the onset of the 2024 wildfire season was notable and posed unique challenges.

A large-scale monitoring and response plan was created in the fall of 2023 to address the potential for overwintering fires resurfacing and growing beyond their established perimeter. As a result of these efforts, only 12 areas saw growth beyond existing perimeters.

Fuel conditions and weather events

Over the past three years, B.C. has been enduring a rainfall deficit, most notably in the central and northeast regions of the province. Quantities measured between September 2023 and September 2024 were about 40 to 60 per cent of normal.

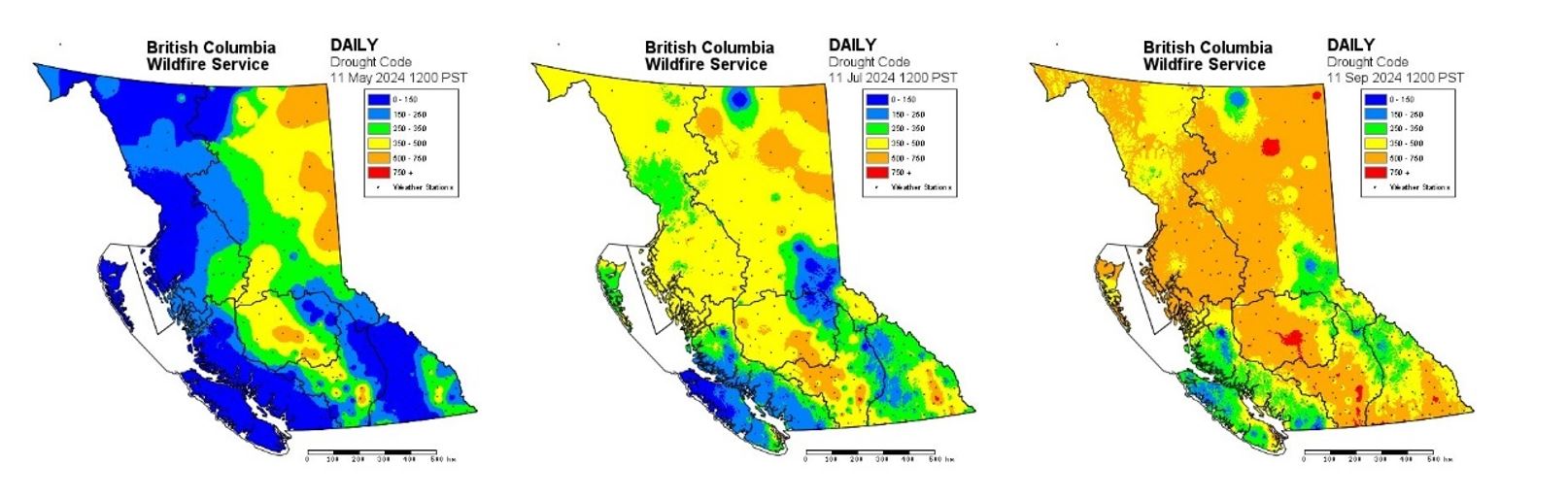

Drought conditions steadily heightened from May through September this season, illustrated by the Drought Code maps below. These conditions have persisted across the northern two-thirds of the province, whereas the southern third experienced near-normal temperatures and above-average rainfall in August, which were favourable in dampening drought values.

During July and August, the number of lightning strikes were 75 per cent of the 20-year average, showing a lower frequency than usual. However, due to the dry, susceptible fuel, lightning accounted for a higher percentage (over 70 per cent) of wildfires this season compared to previous years (typically about 60 per cent).

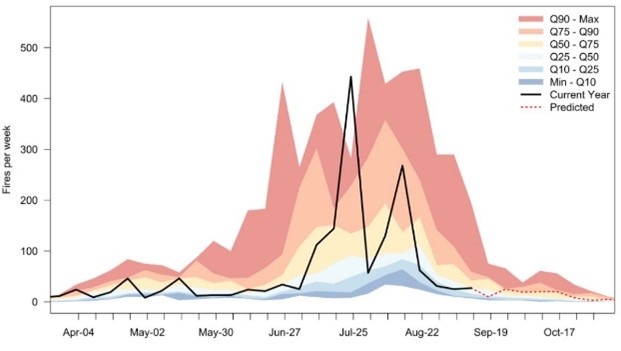

This graph illustrates weekly wildfire activity compared to historical activity. The shaded colours represent percentiles of the last 20 years of historic wildfires week to week. The black line represents 2024 fire activity and highlights two large spikes of fire activity: one in late July and one in mid-August.

Significant incidents

Since April 1, 2024, more than 1,680 wildfires resulted in an estimated 1.08 million hectares of land burned.

Five BC Wildfire Service Incident Management Teams (IMTs) and three IMTs from out-of-province were deployed to major incidents or wildfire complexes across the province to help relieve fire centres and zones in areas of concentrated fire activity. In total, these teams were deployed 27 times. These teams rotated in two-week increments, tirelessly working alongside other emergency and land management personnel including local governments, First Nations and community representatives to achieve containment objectives.

The following table lists the notable wildfires of 2024. The table is filterable by any heading. The wildfire complexes were made of multiple fires, some of which are not listed in this table.

| Fire Name (Number) | Fire Centre | Wildfire Complex | Suspected Cause | Size (ha) | Discovery Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patry Creek (G90207) | Prince George | North Peace Complex | Natural | 170,807 | May 2 |

| Nogah Creek (G90228) | Prince George | North Peace Complex | Natural | 508,453 | May 5 |

| Parker Lake (G90267) | Prince George | North Peace Complex | Human | 12,348 | May 10 |

| Hook Creek (R90740) | Northwest | N/A | Natural | 355 | July 7 |

| Little Oliver Creek (R50752) | Northwest | N/A | Human | 219 | July 8 |

| Shetland Creek (K70910) | Kamloops | Shetland Complex | Natural | 27,956 | July 12 |

| Calcite Creek (K61067) | Kamloops | N/A | Natural | 6,684 | July 17 |

| Argenta Creek (N71058) | Southeast | Lavina Complex | Natural | 19,153 | July 18 |

| Sitkum Creek (K41109) | Kamloops | N/A | Natural | 1,262 | July 18 |

| Aylwin Creek (N51065) | Southeast | Slocan Lake Complex | Natural | Merged with Komonko Creek wildfire | July 18 |

| Ponderosa FSR (N51069) | Southeast | Slocan Lake Complex | Natural | 1,859 | July 18 |

| Mulvey Creek (N51117) | Southeast | Slocan Lake Complex | Natural | 2,235 | July 18 |

| Komonko Creek (N51210) | Southeast | Slocan Lake Complex | Natural | 4,082 | July 19 |

| Antler Creek (C11303) | Cariboo | Groundhog Complex | Natural | 14,277 | July 20 |

| Wilson Creek (N51614) | Southeast | Slocan Lake Complex | Natural | 20 | July 24 |

| Dogtooth FSR (N21427) | Southeast | South Rockies Complex | Natural | 5,680 | July 22 |

| Ravenshead (N21610) | Southeast | South Rockies Complex | Undetermined | 8,615 | July 24 |

| Mount Morrow (N21014) | Southeast | South Rockies Complex | Natural | 11,903 | July 17 |

| Dunn Creek (K21354) | Kamloops | N/A | Natural | 2,577 | July 22 |

| Hullcar Mountain (K41796) | Kamloops | N/A | Natural | 784 | Aug. 4 |

| Lower Blue Mountain (K51866) | Kamloops | N/A | Undetermined | 46 | Aug. 4 |

| Sabina Lake (R11204) | Northwest | Ootsa Lake Complex | Natural | 55,284 | July 19 |

| Mount Wells (R12015) | Northwest | Ootsa Lake Complex | Natural | 14,698 | Aug. 10 |

| Birkenhead Lake (V31836) | Coastal | N/A | Natural | 772 | Aug. 5 |

| Rutherford Creek (V31841) | Coastal | N/A | Natural | 67 | Aug. 6 |

| Old Man Lake (V61401) | Coastal | N/A | Human | 228 | July 22 |

Throughout the season, information officers and videographers worked with operations staff to capture and condense substantial knowledge from experts in the field to inform the public and our partners of ongoing wildfire operations. Pertinent wildfire information was shared regularly through official BC Wildfire Service social media channels, on the BC Wildfire Service web and mobile app, and as operational update videos on our YouTube channel.

Resources

This season, we had approximately 500 permanent and 300 seasonal staff across the province in a variety of technical, operational, support and management roles. Approximately 1,300 wildland firefighters were employed directly by the BC Wildfire Service, with an additional 600 contracted wildland firefighters.

Before the wildfire season became more active across our own province, the BC Wildfire Service was able to provide response support to other wildfire response agencies including Alberta, Yukon, Parks Canada and the United States of America.

The BC Wildfire Service proactively requested nearly 600 resources through the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre to help maintain preparedness and assist with response in all fire centres. Crews and specialized personnel arrived within Canada from Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories, Yukon. Support also came from beyond our borders, with specialized staff coming from the United States of America, Australia and New Zealand. The Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre also produces national wildfire annual reports.

Five Indigenous Initial Response crews from Esket'emc, Simpwc, Skeetchestcn, Canim Lake and Nadleh Whut’en, bolstered response efforts this season, suppressing wildfires within their territory, individually and alongside BC Wildfire Service. Indigenous community response also came in the form of nine Indigenous entry-level crews, nine community liaisons, and six line locator contracts.

Ahead of the 2024 fire season, we worked with partners to train nearly 430 non-Indigenous rural community members across 21 community response groups. Four of these groups were engaged in active fire response this season, including Venables Community, Argenta Community, Knutsford Community, Chinook Emergency Response Society.

We have also expanded our Liaison program, which includes standard contracts for First Nations Community Liaisons and Rancher Representatives, the latter in partnership with the BC Cattlemen’s Association. The individuals who fill these roles are key communications conduits between their community and the BC Wildfire Service and we value the local knowledge they bring.

This year we worked in partnership with numerous structural and municipal fire departments to protect threatened communities. Approximately 84 fire departments deployed to engage in structure protection and wildfire response efforts around the province. The most structure protection personnel deployed on a single day was 251 on July 23.

During the core of the 2024 fire season, there were 33 airtanker and birddog aircraft available to the BC Wildfire Service including resources from Ontario, Quebec, Yukon and Alaska. The airtankers completed 457 missions including 98 practice runs. More than 14.4 million litres of fire suppressant and more than 10.3 million litres of fire retardant were used during these missions. Additionally, dozens of fixed-wing aircraft were utilized for repositioning personnel, reconnaissance and logistical support.

Rotary-wing aircraft were hired in anticipation of increased activity and were extensively used throughout the wildfire season. More than 31,000 hours of flight time was recorded by long term and casual hire helicopters. The greatest number of helicopters hired on a single day was 154 on August 14. Two of the helicopters contracted were equipped to fly with night vision technology. The use of Night Vision Imaging Systems (NVIS) was successfully integrated into our rotary-wing operations in July of this season. NVIS was primarily used for reconnaissance, detection and mapping missions; heli-tanking (dropping water from a belly tank) night operations were also performed on a few select wildfires. Gradually integrating NVIS into wildfire response has proven successful, and we’re excited to add it to our toolbox. Going forward, the BC Wildfire Service intends to build capacity with this technology by training more NVIS observation staff.

Heavy equipment and industry partnerships are essential to wildfire response efforts. Throughout the 2024 wildfire season approximately 100 - 250 pieces of heavy equipment and their operators were available to be contracted to support the BC Wildfire Service. Not only does heavy equipment respond to wildfires around the province, but it is also used for wildfire rehabilitation work.

The efforts of hundreds of personnel which were contracted to provide various fire-related functions including tree falling, first aid, catering and security, were essential for sustaining fire operations. At peak, roughly 300 personnel were contracted for support functions on a single day.

Recovery

Wildfire is a natural event that shapes ecosystems in B.C. While lower intensity wildfires can improve forest health, highly intense and extreme wildfires can have detrimental impacts to our lands and ecosystems. Continuing work in wildfire recovery and rehabilitation will help mitigate the damage to forests from wildfire suppression activities or from the wildfire itself. The BC Wildfire Service has expanded the program this year which covers wildfire suppression rehabilitation, post wildfire natural hazard risk analysis and ecological wildfire recovery. As of October 31, approximately 210 of the 2,061 kilometres of fire guard that was built this season has been rehabilitated, and 28 ecological wildfire recovery projects are underway.

Provincial Statistics

- For year-to-date statistics and historical comparisons, visit the Dashboard of the BC Wildfire Service app.

- Over 70 per cent of wildfires this season were caused by lightning while just under 30 per cent were attributed to human activity. A small percentage remain undetermined or under investigation.

- Wildfires this season resulted in 51 evacuation orders, which affected more than 4,100 properties, and 112 evacuation alerts, which affected more than 12,500 properties.

- The Provincial Wildfire Reporting Centre (PWRC) fielded over 18,000 calls this season, 12,421 of which were wildfire reports. In addition, approximately 1,300 wildfire reports were submitted through the BC Wildfire Service app’s ‘Report a Fire’ function.

- Wildfires in 2023 and 2024 within the Prince George Fire Centre have burned 10 per cent of the land base in the region, which is more than the previous 60 years combined.

- As of November 1, the estimated cost of wildfire suppression was $621 million.

Looking Ahead

Research and Innovation

The BC Wildfire Service continues to make progress on long-term projects with our established partners while exploring new ideas, products and research opportunities. We remain focused on improving the health, wellbeing and safety of BC Wildfire Service staff; contributing to the understanding of wildland fire science and associated sciences (as it applies to wildfire); and harnessing emerging tools and technology for optimal wildfire management strategies.

Ongoing research and innovation projects include:

- Multi-year research into the cardiorespiratory health impacts of wildfire smoke, ash and dust to wildland firefighters and identifying mitigation strategies

- Evaluating advancements in automated wildfire risk and fire growth modelling software to enhance wildfire planning and response

- Investing in satellite data acquisition and hardware that expands our access of heat detection, fuel maps and post-fire analysis products

- Trialing real-time video feed equipped with artificial intelligence (AI) to assist in initial wildfire detection, operational response tactics, situational awareness and monitoring of wildfires

Outlook

The Fall 2024 Seasonal Outlook recaps the spring and summer climatic conditions and multi-year droughts that led into this fire season, which saw the fourth largest yearly area burned in B.C.’s history.

Due to the large areas burned in the Prince George Fire Centre and the existing and potential ongoing drought in that area, overwintering fire conditions may be present in the spring of 2025 in the northeast corner of the province. The BC Wildfire Service will be monitoring these conditions through the fall and winter.

Reflections

The 2024 wildfire season was active early in the year and we faced unique challenges as a result. The impacts were not as widespread as in previous years, but it was still significant to the people and communities affected, as well as to those who responded. Our province and our organization will continue to be resilient and adaptable, taking the events and learnings from this wildfire season to better prepare us for future emergencies and disasters.

Throughout this winter and heading into 2025, we will continue working with our partners to improve cooperation with communities that possess local knowledge and expertise. BC Wildfire Service is developing solutions to expand training and equipment opportunities to communities interested in integrating with our operations in a safe and respectful way.

To learn more about how the BC Wildfire Service operates across all four pillars of emergency management, please explore the rest of this site.

2023 Wildfire Season Summary

The 2023 wildfire season has been the most destructive in British Columbia’s recorded history:

- More than 2.84 million hectares of forest and land burned

- Tens of thousands of people forced to evacuate

- Hundreds of homes and structures lost or damaged

- Impacts to cultural values, ecological values, infrastructure and local economies

- Indirect economic impacts to agriculture, tourism and other weather-dependent businesses

- Unquantifiable impacts to people’s health and wellbeing

This season has been emotionally challenging and will always be remembered for the tragic loss of six members of B.C.’s wildland firefighting community. These individuals exhibited remarkable courage, dedication and selflessness, and their memory will continue to be honoured. Thank you, Devyn Gale, Zak Muise, Kenneth Patrick, Jaxon Billyboy, Blain Sonnenberg and Damian Dyson for serving and protecting the lands and people of British Columbia.

Watch the 2023 season summary video to see the season through the eyes of our people.

Provincial Statistics

Between April 1 and October 31, 2,245 wildfires burned more than 2.84 million hectares of forest and land. This is the most hectares burned in a wildfire season in B.C.’s recorded history.

Though the number of wildfires and hectares burned are significant, 80 per cent of wildfires this season were contained at five hectares or less.

Other years saw more total fires. Twelve seasons have had over 3,000 fires from April 1 to October 31, with 1970 holding the record with 3,990 fires.

Hectares burned this year are double the last record of 1.35 million in 2018. This amount is 10 times the 20-year average annual area burned (284,001 hectares) and is what would historically be expected over a decade. The table below compares 2023 to other significant wildfire seasons (from April 1-October 31).

|

Year |

Number of Wildfires |

Hectares Burned |

|---|---|---|

|

2023 |

2,245 |

2,840,545 |

|

2021 |

1,625 |

869,270 |

|

2018 |

2,080 |

1,355,271 |

|

2017 |

1,332 |

1,215,685 |

Of the 2,245 wildfires, 72 per cent were natural-caused and 25 per cent were human-caused. For the remaining three per cent of wildfires, the causes are undetermined.

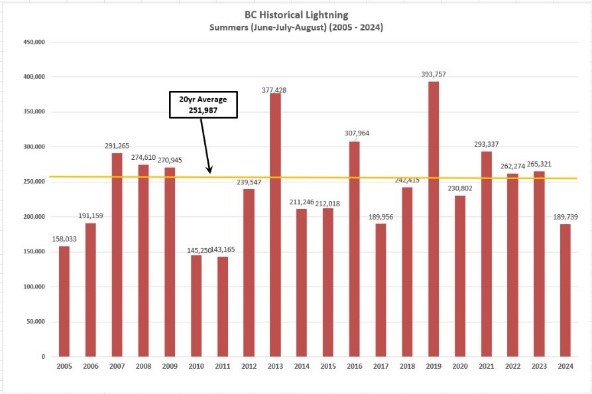

The number of lightning strikes during the 2023 wildfire season was slightly above the 20-year average, with 265,321 strikes recorded.

There were 60 wildfires designated as Wildfires of Note. A Wildfire of Note is a wildfire that is highly visible or poses a threat to public safety.

The estimated cost of wildfire suppression is $1,094.8 million.

For 28 days, B.C. was under a provincial state of emergency.

Wildfires this season resulted in:

- An estimated 208 evacuation orders which affected approximately 24,000 properties and roughly 48,000 people

- An estimated 386 evacuation alerts which affected approximately 62,000 properties and roughly 137,000 people

The number of structures impacted is not yet available, as communities are still assessing and gathering the information to share with the Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness.

Between April 1 and September 30, 29,900 calls were made to the Provincial Wildfire Reporting Centre, generating 18,200 wildfire reports. More than 1,800 wildfire reports were made via the ‘Report a Fire’ function in the BC Wildfire Service mobile app.

Conditions and Fire Behaviour

British Columbia experienced one of the warmest and driest Octobers in 2022. Daytime highs were consistently four to 10 degrees above normal and there was very limited precipitation for what is typically a cool and wet month. Due to the limited moisture, drought conditions in the forests were much higher than normal. The elevated drought codes carried over into spring 2023 and set the stage for a potentially active fire season.

Valley bottoms and deeper fuel layers continued to be very dry from the fall and into April as there was little to no precipitation received, making forest fuels easily susceptible to ignition. Unusually advanced fire behaviour was observed as a result of the drought conditions, considering how early in the spring it was.

In May, an early season heatwave delivered temperatures six to 10 degrees above normal. Rainfall amounts were considerably lower than historical norms, with some areas receiving half of their average amount of precipitation. Nineteen of 23 Environment Canada weather stations recorded a drier than normal May. Sixteen of 23 Environment Canada weather stations recorded the warmest May on record. The exceptional summer-like conditions accelerated snow melt and the drying of fuels, making high-elevation areas snow-free and therefore receptive to lightning two to four weeks earlier than normal.

The lightning-caused Donnie Creek wildfire (G80280) was discovered on May 12, 136 kilometres southeast of Fort Nelson. It exhibited aggressive fire growth, taking a 30 kilometre run just five days after receiving 40 millimetres of rain. Early season burning conditions were equally elevated on Vancouver Island. The Newcastle Creek wildfire (V80527) discovered on May 29, burned nearly a metre deep into the ground.

In June and July, temperatures were significantly above historical averages. Many weather stations in B.C. recorded monthly temperatures in their top ten warmest ever recorded. In addition to the prolonged hot conditions, rainfall was very limited with only 20 to 60 per cent of normal rainfall being received. Lightning activity also increased significantly. Between July 7 and July 13, 51,000 lightning strikes were recorded in B.C., with 76 per cent of those concentrated in the Northwest and Prince George Fire Centres. As a result, 399 new wildfires started in that seven-day period.

Conditions through early August were much of the same – hot and dry. Between August 15-18, over 40 new temperature records were set. This heatwave was followed by a dry cold front which spread strong gusting winds of 40 to 60 kilometres per hour for a 24-hour period from B.C.’s northwest, through Interior regions, before finally passing through the province’s southeast corner. Following the extreme heat and strong wind event, numerous wildfires exhibited extreme fire behaviour and spread exponentially, including the Kookipi Creek wildfire (V11337) near Boston Bar, the Downton Lake wildfire (K71649) near Gold Bridge, the Casper Creek wildfire (K71535) near Shalalth, the Crater Creek wildfire (K52125) near Keremeos, the McDougall Creek wildfire (K52767) adjacent to West Kelowna and the Bush Creek East (K21633) and Lower East Adams Lake (K21620) wildfires in the Shuswap, which merged as a result.

September brought no reprieve for northern B.C. Conditions were persistently warm and dry, coupled with repeated cold front passages. Significant increase in wind speeds and shifting directions lasted over multiple days multiple times over the month. The wind events supported increased activity on longstanding fires across northern B.C., spreading 10 to 40 kilometres in one day.

Fire Activity

Fire Centre Statistics

|

Fire Centre |

Number of Wildfires |

Hectares Burned |

|---|---|---|

|

Cariboo Fire Centre |

247 |

53,648 |

|

Coastal Fire Centre |

365 |

89,750 |

|

Kamloops Fire Centre |

388 |

201,385 |

|

Northwest Fire Centre |

277 |

174,796 |

|

Prince George Fire Centre |

672 |

2,276,938 |

|

Southeast Fire Centre |

296 |

44,027 |

At the peak of wildfire activity, there were 481 wildfires burning concurrently.

Wildfires of Note

In 2023, 60 wildfires were classified as Wildfires of Note. A Wildfire of Note is a fire that is particularly visible or posing a threat to public safety. All 2023 Wildfires of Note are listed in the below table. The table can be searched or sorted by fire name alphabetically, or by hectares burned.

| Fire Centre | Fire Name | Fire Number | Hectares Burned | Date of Discovery | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cariboo | 4.3km SE of Teepee Lake | C11499 | 7,864 | 10-Jul | Natural |

| Cariboo | 2.5km N of Pelican Lake | C11437 | 4,422.1 | 09-Jul | Natural |

| Cariboo | Townsend Creek (2.5km E of Margaret Lake) | C11290 | 2,784.7 | 08-Jul | Natural |

| Cariboo | E of Dripping Water Rd | C50100 | 209.0 | 27-Apr | Human |

| Cariboo | 3.3km SW of Pelican Lake | C50354 | 145.0 | 17-May | Human |

| Coastal | Kookipi Creek | V11337 | 17,405.9 | 18-Aug | Natural |

| Coastal | Young Creek | VA1735 | 3,360.0 | 15-Jul | Natural |

| Coastal | Dean River | VA1335 | 2,337.6 | 08-Jul | Natural |

| Coastal | E of Chehalis River | V10588 | 767.2 | 03-Jun | Human |

| Coastal | Cameron Bluffs | V70600 | 229.0 | 03-Jun | Human |

| Coastal | 0.5km N Davis Lake | V11152 | 215.0 | 05-Jul | Human |

| Kamloops | Lower East Adams Lake | K21620 | Merged with Bush Creek East | 12-Jul | Natural |

| Kamloops | Crater Creek | K52125 | 46,504.2 | 22-Jul | Natural |

| Kamloops | Bush Creek East | K21633 | 45,613.0 | 12-Jul | Natural |

| Kamloops | McDougall Creek | K52767 | 13,970.4 | 15-Aug | Undetermined |

| Kamloops | Rossmoore Lake | K22024 | 11,382.0 | 21-Jul | Natural |

| Kamloops | Casper Creek | K71535 | 11,284.0 | 11-Jul | Natural |

| Kamloops | Downton Lake | K71649 | 9,565.0 | 13-Jul | Natural |

| Kamloops | Eagle Bluff | K52318 | 7,060.6 | 29-Jul | Undetermined |

| Kamloops | Stein Mountain | K71634 | 4,734.3 | 12-Jul | Natural |

| Kamloops | Upper Park Rill Creek | K52813 | 2,043.8 | 18-Aug | Human |

| Kamloops | Glen Lake | K53294 | 1,116.2 | 16-Sep | Human |

| Kamloops | Knox Mountain | K51040 | 6.3 | 01-Jul | Human |

| Northwest | Sheraton Creek | R11247 | Merged with Tintagel | 07-Jul | Natural |

| Northwest | Tintagel | R11244 | 8,044.0 | 07-Jul | Natural |

| Northwest | Parrot Lookout | R21234 | 6,758.0 | 07-Jul | Natural |

| Northwest | Old Man River | R21250 | 2,061.0 | 07-Jul | Natural |

| Northwest | 600m W of Peacock Creek | R21178 | 1,444.7 | 06-Jul | Natural |

| Northwest | 3mi SW Nilkitkwa Dam | R31465 | 639.0 | 09-Jul | Natural |

| Northwest | Powers Creek | R31228 | 34.0 | 07-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | West of Cameron River | G80175 | 385.0 | 01-May | Human |

| Prince George | Coffee Creek | G80190 | 89.0 | 03-May | Human |

| Prince George | Teare Creek | G30210 | 1,100.0 | 04-May | Human |

| Prince George | Boundary Lake | G80220 | 6,422.2 | 05-May | Human |

| Prince George | Red Creek | G80223 | 2,947.0 | 05-May | Human |

| Prince George | Donnie Creek | G80280 | 619,072.5 | 12-May | Natural |

| Prince George | Stoddart Creek | G80291 | 29,505.9 | 13-May | Human |

| Prince George | West Kiskatinaw River | G70645 | 25,095.0 | 06-Jun | Natural |

| Prince George | Peavine Creek | G70644 | 4,427.0 | 06-Jun | Natural |

| Prince George | Big Creek (Omineca River) | G60666 | 166,856.9 | 07-Jun | Natural |

| Prince George | Nation River | G60853 | 22,372.8 | 23-Jun | Natural |

| Prince George | Klawli Lake | G50872 | 17,333.8 | 24-Jun | Natural |

| Prince George | Tsah Creek | G41149 | 501.1 | 05-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | Gatcho Lake | G41158 | 21,926.5 | 06-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | Finger Lake | G41195 | Merged with Tatuk Lake | 07-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | Great Beaver Lake | G51279 | 48,396.3 | 08-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | Tatuk Lake | G41307 | 44,641.7 | 08-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | South Lucas Lake | G41380 | Merged with North Lucas Lake | 09-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | Nithi Mountain | G41422 | 736.6 | 09-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | North Lucas Lake | G41502 | 34,853.6 | 10-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | Davidson Creek | G41493 | 4,878.8 | 10-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | Greer Creek | G41511 | 4,767.8 | 10-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | SW Whitefish Lake | G51564 | 6,143.2 | 11-Jul | Natural |

| Prince George | Mount Wartenbe | G73406 | 1,246.0 | 08-Oct | Natural |

| Southeast | St. Mary's River | N11805 | 4,640.0 | 17-Jul | Human |

| Southeast | Horsethief Creek | N22243 | 3,918.5 | 24-Jul | Natural |

| Southeast | Lladnar Creek | N12046 | 1,295.0 | 21-Jul | Natural |

Wildfire Complexes

With the high number of wildfires throughout B.C., many Wildfires of Note and other wildfires in similar locations were grouped into “complexes”. A complex is created when multiple wildfires are managed by a single Incident Management Team, and resources and equipment are shared between all incidents in the complex. There were 14 complexes in 2023:

- Gillies Complex, Cariboo Fire Centre: Pelican Lake (C11437), Teepee Lake (C11499), Townsend Creek (C11290), Branch Road (C11243), Trout Lake (C11308)

- Kappan Complex, Cariboo Fire Centre: Gatcho Lake (G41158), Moose Lake (G41189) which merged with Gatcho Lake, Lily Lake (G41165) which merged with Gatcho Lake, Corkscrew Creek (C11405), Trumpeter Mountain (VA1456), Anahim Peak (C51571), Elbow Lake (VA1462), Young Creek (VA1735), Grizzly Creek (VA1167), Irene Lake (C11892), Satah Mountain (C51562)

- Kookipi Complex, Coastal Fire Centre: Kookipi Creek (V11337), Texas Creek (K71415), Stein Mountain (K71634), Ponderosa Creek (K71705), Rutledge Creek (K71707), Cottonwood Creek (K72705), Izman Creek (K72771)

- Adams Complex, Kamloops Fire Centre: Bush Creek East (K21633), Lower East Adams Lake (K21620) which merged with Bush Creek East, Rossmoore Lake (K22024)

- Bendor Range Complex, Kamloops Fire Centre: Downton Lake (K71649), Casper Creek (K71535), Blackhills (K71778)

- Crater Complex, Kamloops Fire Centre: Crater Creek (K52125), Upper Park Rill Creek (K52813)

- Grouse Complex, Kamloops Fire Centre: McDougall Creek (K52767), Walroy Lake (K52808), Clarke Creek (K42815), Glen Lake (K53294)

- Donnie Creek Complex, Prince George Fire Centre: Donnie Creek (G80280), West Conroy Creek (G80287) which was consumed by Donnie Creek, Katah Creek (G80274) which was consumed by Donnie Creek, Kahntah River (G81157) which was consumed by Donnie Creek, Klua Lakes (G90273), Muskwa River (G90292), Zaremba Creek (G80875), Beatton River (G81492), Milligan Hills (G81530), Fontas River (G81010) which was consumed by Hay River (G90628)

- North Peace Complex, Prince George Fire Centre: Cameron River (G80175), Boundary Lake (G80220), Red Creek (G80223), Stoddart Creek (G80291)

- Omineca Complex, Prince George Fire Centre: Big Creek (G60666), Nation River (G60853), Usilika Lake (G60882) which was consumed by Big Creek, Mesilinka River (G60651) which was consumed by Big Creek, Fall River (G50851) which was consumed by Big Creek, Muscovite Lakes (G60655), Porcupine Mountain (G60861)

- South Peace Complex, Prince George Fire Centre: Peavine Creek (G70644), West Kiskatinaw River (G70645)

- Elk Complex, Southeast Fire Centre: Lladnar Creek (N12046), Mount Bingay (N12546)

- Horsethief Complex, Southeast Fire Centre: Horsethief Creek (N22243), Yearling Creek (N21453), Mia Creek (N22240), Jubilee Mountain (N22370), Schofield Creek (N22508)

In some cases, fire zones had anywhere from 15 to 50 active fires burning concurrently. To manage the situation, Ministry Zone Operations Centres (MZOCs) were stood up. MZOCs provided support and coordinated response efforts and resources for the defined areas experiencing heavy wildfire demands. Every fire centre had a zone or zones that activated MZOCs.

Fire Bans

Over the season, all fire centres implemented Category 1 (campfire), Category 2 and Category 3 open fire prohibitions. Fire prohibitions are put into place on a regional basis to prevent human-caused wildfires. Many factors are taken into consideration when deciding to implement or rescind an open fire prohibition including fire danger ratings, fuel conditions, local hazards, current and forecasted wildfire activity, as well as current and forecasted weather. Conditions are assessed constantly to make well-informed decisions that best serve our province. Learn more about the science behind open fire prohibitions on our YouTube channel.

The public’s responsible and safe use of fire, or any activity that may have caused a wildfire, was key in keeping overall human-caused wildfires low.

Cultural and Prescribed Fire

Prescribed and cultural fire was utilized throughout the spring and fall for a variety of objectives, including wildfire risk reduction for protection of communities and critical infrastructure, ecosystem restoration, silviculture objectives such as site preparation and habitat objectives. A total of 23 burning projects covering 2,241.4 hectares were completed.

Wildfire reduction activities, such as cultural burning and prescribed fire, can help mitigate large-scale wildfires and their negative impacts on air quality, health, and safety. Fostering collaboration with local communities and the public regarding the importance of reintroducing fire to the landscape in a planned and controlled way, either from a cultural or prescribed fire perspective, is of the utmost importance. These practices are conducted in short intervals and under conditions that limit unintended smoke impacts. To prevent damage and disaster which result from uncontrolled wildfires, and to maintain the health and safety of our forests, communities and wildlife, cultural and prescribed fire will continue to become a more common practice.

Resourcing

Our organization went into the 2023 wildfire season with approximately 2,000 firefighting and support personnel.

Before wildfire activity in B.C. escalated, we were able to assist neighbouring jurisdictions and partners who were facing heightened fire activity. Our firefighters and specialized staff supported in Alberta, Quebec and Alaska.

Upwards of 1,100 personnel were contracted to provide various fire-related functions, including fire suppression, tree falling, first aid, catering and security.

We worked in partnership with numerous structural and municipal fire departments to protect threatened communities. Approximately 135 fire departments to deployed to wildfire incidents 646 times.

Five Indigenous Initial Response crews bolstered response efforts, suppressing wildfires within their territory, individually and alongside BC Wildfire Service.

Heavy equipment and operational partnerships were, as always, imperative to wildfire response this fire season. More than 450 pieces of heavy equipment and their operators responded to wildfires across the province. Operating side-by-side with firefighters, heavy equipment is primarily engaged to build guards that support or make use of existing fuel breaks, including roads and natural features (such as rivers), to minimize additional damage to the natural environment. Learn more about heavy equipment operations on the fireline on our YouTube channel. In addition to providing operational support, as well as local knowledge and expertise, we rely heavily on the contracting community to assist with the rehabilitation of damage due to fire suppression related activities. West Fraser, Western Forest Products, Canfor, Interfor, Tolko, Interior Lumber Manufactures Association, Interior Logging Association and the Council of Forest Industries provided invaluable support.

More support came from hundreds of other local partners in First Nations communities and governments, the forest and ranching sectors, local governments and other ministries, all with diverse and valuable skillsets. The regional knowledge and expertise brought by our partners helps our staff and crews make informed choices about response tactics while making the smallest impact to ecosystems, other values including culturally significant resources and timber.

As wildfire activity increased in June and July, significant out-of-province resources were mobilized to support efforts within the province. Approximately 1,750 personnel came from out-of-province to support the wildfire fight in B.C. Assistance came from Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, the Yukon, the Canadian Armed Forces, the United States of America, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, Brazil, Costa Rica and South Africa.

Our partners at the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and Australia’s Forest Fire Management Victoria provided specialized support in response planning and operations. They exchanged knowledge with us which will help inform future technology and decision-making regarding fire intelligence, advanced planning and fire growth modelling.