Fall Prevention: Risk Assessment and Management for Community-Dwelling Older Adults

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Epidemiology

- Risk Factors

- Evaluating Patients for Fall Risk

- Patient Evaluated as at Risk: Multifactorial Risk Assessment, Fall History and Intervention

- Follow up

- Patient Evaluated as Not at Risk of Falls

- Referral Options

- Appendices

- Associated Documents

- Resources

- References

Scope

This guideline addresses the identification and management of older adults aged ≥ 65 years living in the community with risk factors for falls, and is intended for primary care practitioners. The guideline facilitates individualized assessment and provides a framework and tools to manage risk factors for falls and fall-related injuries. Hospital, facility-based care settings and acute fall management are outside the scope of this guideline, although some of the principles in this guideline may be useful in those settings.

Key Recommendations

- Annually, or with a significant change in clinical status, ask patients ≥ 65 years about their fall risk using simple one-minute screening tools to identify people at risk of falls:

- Recommend exercise to improve strength and balance and safe mobility. This is the most effective fall prevention intervention.1–5 See Exercise Prescription and Programs below.

- For those evaluated as “at risk” or who have had a fall, a multifactorial risk assessment is recommended over multiple visits to review (see Multifactorial Risk Assessment, Fall History and Intervention section):

- Medications

- Medical conditions (including review of common geriatric conditions)

- Mobility (endurance, strength, balance and flexibility)

- An assessment of the home environment

- Osteoporosis risk assessment and management (increases risk of fracture from fall)

- After a fall, interdisciplinary assessment and care planning can reduce the risk of future falls. A team-based approach, when available, is recommended (see Referral Options section).

Epidemiology

Incidence of Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among British Columbians Aged ≥ 65 Years

- One in three fall annually in the community setting.6

- One hospitalization every 30 minutes, with 83% from community and 17% from facility-based care.7

- Every day ~3 older adults die from a fall. ~1,000 direct and indirect deaths annually.7

- Forecasted to continue increasing with population aging.8 There was a 33% increase in hospitalizations from 2009-2016.7

Burden of Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among British Columbians Aged ≥ 65 Years

- Annual total cost (including emergency room visits, hospitalized treatment, permanent disability, and cost of deaths) is $1.4 billion.9,10 Annual total cost does not include societal costs, such as the cost of reduced quality of life, reduced productivity for older adults (e.g., informal caregiving, volunteering, and employment) and reduced productivity for family caregivers.

- 10-15% of falls result in serious injuries including fractures and head injuries.11

- Falls are the cause of 40% of admissions to facility-based care.12

- Falls are the cause of 95% of hip fractures.7

- 30% die within the following year,7 this reflects their increasing frail status.13

- 50% lose mobility and independence.7

Prevention of Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among Older Adults Aged ≥ 65 years

- Most falls are predictable and preventable (see the Associated Document: Facts About Falls).

- Older adults are unlikely to initiate a conversation about fall risk, even if they have sustained injuries from falls in the past.

- Older adults under-recognize their fall risk and under-report falls. They have low awareness that most falls are preventable and are not a normal part of aging.

- Clinical assessment by a healthcare provider and multifactorial interventions to address predisposing factors can decrease falls by approximately 25% among those at high risk.14,15

- Screening and interventions to reduce falls in community-dwelling older adults at the primary care level is cost effective (estimated at $35,213 per Quality Adjusted Life Years).16

Risk Factors

Falling is an indicator of a complex system failure requiring multifactorial assessment and intervention.13 These can be categorized into four dimensions: biological, behavioural, environmental and socioeconomic factors (see Table 1). Medical conditions that cause gait and balance problems are reviewed in Appendix A: Medical Conditions Associated with Gait and Balance Disorders.17,18

- Frailty and multi-morbidity, not increasing age, is the primary consideration in fall risk. For those ≥ 80 years, 60% fell over a 12-month period, reflecting their frail status.19–21

- Fear of falling results in self-imposed activity restrictions and further functional decline, depression, feelings of helplessness, and social isolation.22 This fear in turn increases risk of falling.

- Older adults often misattribute a fall to “bad luck” or an environmental hazard. In reality, “tripping” reflects an inability to compensate and prevent the fall from occurring.23–25

- Less than half who fell recently will disclose falling to their healthcare providers.26,27 Admitting falls may carry its own stigma around weakness or frailty and can be met with embarrassment, fear, or avoidance.

- Older adults have low awareness of the multifactorial interventions that can prevent falls.28

Table 1. Risk Factors Associated with Falls and Fall-Related Injury18,22,29–40

Major risk factors that have the strongest associations for prediction of falls

- Overarching Factor: History of falls, especially multiple falls41

- Advanced age

- Medication (psychotropics, antipsychotics, sedative/hypnotics, antidepressants, see Appendix C: Medications Contributing to the Risk of Falling)

- Functional decline: limitations in any activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)

- Medical and/or psychiatric comorbidity

- Lower body weakness

- Difficulties with gait and balance

- Visual impairments

- Urinary incontinence/rushing to the bathroom

- Pain and stiffness from arthritis

- Depression

Additional risk factors associated with falls and fall-related injury

Medical/Biological/Intrinsic Factors

- Frailty

- Refer to Appendix A: Medical Conditions Associated with Gait and Balance Disorders for medical conditions that cause gait and balance problems

Functional Changes

- Impaired mobility

- Balance deficit

- Functional decline: limitations in any ADLs or IADLs

- Urinary and/or bowel incontinence/urgency

Behavioural Factors

- Fear of falling

- Communication (e.g., language barriers, aphasia, literacy level)

- Risk-taking behaviours

- Impaired safety awareness, impulsivity

- Lack of exercise

- Inappropriate footwear/clothing

- Misuse of assistive devices, inappropriate devices

- Poor nutrition

- Dehydration/inadequate fluid intake

Socioeconomic Factors

- Lower level of education

- Poor living conditions

- Living alone

- Lack of support networks/social interaction

- Inadequate support to caregiver for dependant elderly42–44

- Lack of transportation

Environmental Factors

- Stairs

- Home hazards (clutter, see Associated Document: Checklist for Preventing Falls at Home)

- Inadequate lighting

- Inadequate visual contrast with a change in surface of level

- Seasonal weather hazards (e.g., rain, ice, snow, see Patient Handout: Tips to Stay Fall Free in Winter)

- Poor building design and/or maintenance.

- Lack of: handrails, curb ramps, rest areas, grab bars

- Obstacles/tripping and slipping hazards: pets, cords, rugs, furniture

Evaluating Patients for Fall Risk

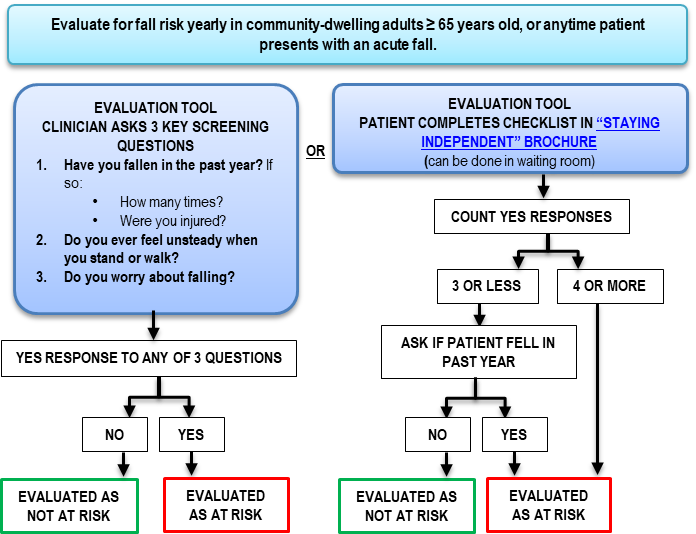

Annually evaluate fall risk in patients ≥ 65 years using one of two evaluation tools (see text below and Figure 1).45,46

Reassess for fall risk if there is a significant change in the patient’s health: physical, cognitive, mental status, behavioural, mobility, medication changes, social network or environment.47–49

One of two evaluation tools can be used to assess patient fall risk (see Figure 1 below):50

1. Primary care practitioner asks 3 questions (could be done in one minute):

- Ask the following questions, as needed:

- Have you fallen in the past year? If so:

- How many times?

- Were you injured?

- Do you ever feel unsteady when you stand or walk?

- Do you worry about falling?

If the patient answers “yes” to any of the three questions above, carry out a multifactorial risk assessment and fall history.

2. Staying Independent Checklist (can be done in the waiting room):

Ask the patient or their caregiver to complete the Staying Independent Checklist to identify major fall risk factors (see the Associated Document: Staying Independent Checklist)

The Staying Independent Checklist can be made available in the office as a handout and distributed by other healthcare providers (e.g., nurse or medical office assistant [MOA]).

Figure 1: Staying Independent Checklist

Patient Evaluated as at Risk: Multifactorial Risk Assessment, Fall History and Intervention

Falls History and Assessment of Modifiable Risk Factors

For patients with multiple health concerns, consider using “rolling” assessments over multiple visits, targeting at least one area of concern at each visit.

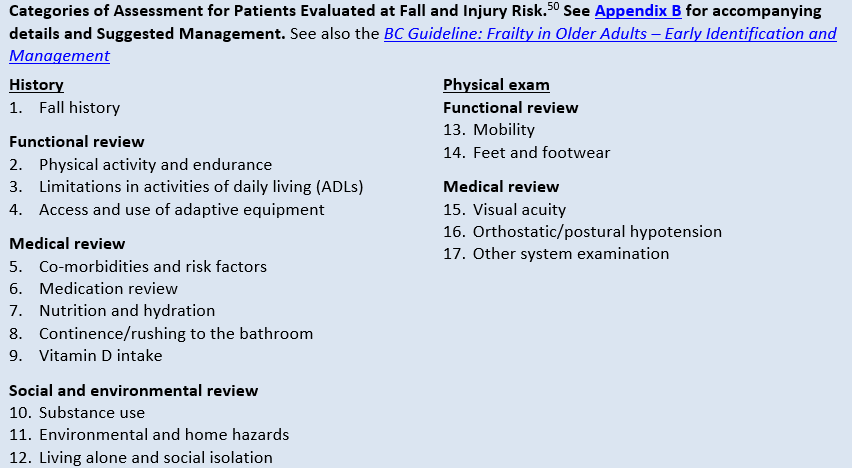

Interventions are recommended for patients based on their individualized multifactorial risk assessment (see Figure 2 below and Appendix B: Categories of Assessment for Patients Evaluated at Fall and Injury Risk (with suggested management)).

The single most effective fall prevention intervention is participation in a safe exercise program designed to improve strength and balance.1–5 See Exercise Prescription and Programs below.

All other fall prevention interventions are effective when completed in combination.

Fall prevention quality improvement strategies proven to reduce falls include: education and reminders for patients and team changes, case management and staff education for clinicians.51

Figure 2: Categories of Assessment for Patients Evaluated at Fall and Injury Risk50

See Appendix B for accompanying details and suggested management. See also the BC Guidelines.ca: Frailty in Older Adults – Early Identification and Management

Follow-Up

- For those with an intervention care plan, follow-up with patient in 30-90 days to discuss the care plan’s value and discuss ways to improve patient receptiveness to the care plan.

- Older adults may struggle with changing their health behaviours. Frequent, brief follow-up discussions focused on barriers and facilitators are recommended.

- For suggested motivational interviewing responses see the Talking about Fall Prevention with Your Patients resource.

- To advise a patient on how to manage after a fall, see HealthLinkBC.ca: How to Get Up Safely After a Fall

Older adults may also wish to promote fall prevention when talking to their family and friends.

Patient Evaluated as Not at Risk of Falls

Consider the opportunity to discuss the following to reduce future risk:

- Educate the patient on fall and injury prevention (see the patient brochure from the US CDC What You Can Do to Prevent Falls and Patient Handout: Facts About Falls).

- Reassess annually, or if patient presents with a fall.

- To maintain low risk category, encourage proactive participation in strength and balance exercise or fall prevention program, including community or online.

Referral Options

See the Patient Handout: Referral Options Resource Guide for Patients and Caregivers

Exercise Prescription and Programs

- The single most effective fall prevention intervention is participation in a safe exercise program designed to improve strength and balance.1–5

- Older adults can check with their community centre, physiotherapist or call HealthLink BC at 8-1-1 (or 7-1-1 for the deaf and hard of hearing) to speak with a qualified exercise professional for exercise prescription or to learn more about individual or group exercise options.

- For older adults who prefer to engage in physical activity at home, exercise videos are available online: findingbalancebc.ca: Exercise.

Best practice recommendations for falls prevention exercise: 14,47,52

General considerations:

- Should be tailored to the individual (i.e., pitched at the right level, taking falls history, functional ability and medical conditions into account).53

- Should be delivered by specially trained instructors to ensure appropriate increases in intensity.

- Care should be taken to ensure it is carried out in a manner that does not increase the risk of falling.

Type of exercise:

- Exercise should provide progressive challenge to balance. Strength training and walking may be included in addition to balance training. High-risk individuals, however, should not be prescribed brisk walking programmes.54

- Adherence to exercise routines increases with levels of enjoyment; it is important to recommend physical activity on an individual basis centered on goals, current fitness level, and health status.23

- Evidence informed exercise programs include: Osteofit (including Get Up & Go!) and Physical Activity Services (offered through HealthLink BC/8-1-1).

- Other forms of exercise which may increase balance and strength (e.g., yoga, Pilates, tennis, dancing) have many benefits but may be insufficient in themselves for falls prevention. Supplemental activities may be considered.3,5,55

Frequency and duration:

- Adults ≥ 65 years should accumulate at least 150 minutes of exercise per week in bouts of 10 minutes or more.56,57

- Older adults at risk of falling should do balance training for three or more days per week.53

Geriatric Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine (hospital, private office)/falls clinic or practitioner specializing in the care of the elderly.

- Determine if your community has a specific falls prevention clinic or a multidisciplinary geriatric clinic (e.g., Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver Coastal Health, Fraser Health, Providence Health Care).

Home and Community Care

- Primary care practitioners play an essential role in identifying patients in need of increased supports and facilitating intake into the system of care support. Ensure patients and caregivers in need of support are referred to local health care and social services, which are available from both publicly subsidized and private pay providers.

- For help finding information on social and health resources in your local community, see BC211 at www.bc211.ca

- Case managed services available to eligible patients through Home and Community Care within local health authorities include:

- community nursing for acute, chronic, palliative or rehabilitative support

- community occupational therapist, physiotherapist, dietician consultation as available and appropriate

- services for personal care, health care and social and recreational activities

- home support for assistance with activities of daily living

- caregiver respite/relief

- adult day care, assisted living and facility-based care

- end-of-life care services

- For more information, see www2.gov.bc.ca: Home and Community Care or contact your local health authority.

- Consider directing caregivers to www.FamilyCaregiversBC.ca and the BC Family Caregiver Support Line at 1-877-520-3267.

Advance Care Planning

- Falls commonly accompany severe frailty and advance care planning is advised.

- See BCGuidelines.ca: Frailty in Older Adults – Early Identification and Management and Advance Care Planning: Resource Guide for Caregivers and Patients for further information on advance care planning.

Vision Correction – Ophthalmologist and Optometrist

- A referral is not required for an optometrist visit however some extended health plans do require one. See: bc.doctorsofoptometry.ca/find-a-doctor/

- According to the BC Optometrist fee schedule, the Medical Services Plan provides limited or partial coverage as a benefit for optometric services in adults (bc.doctorsofoptometry.ca/patients/medical-services-plan/):

- Adults aged 19–64: eye exams not covered by MSP unless medically required

- Seniors aged 65+: one full eye examination annually

- A referral is required to see an ophthalmologist. See: BCSEPS.com: Directory of Eye Physicians and Surgeons

Diagnostic Codes

ICD-9 codes: E880-E88858

ICD-10 codes: W00-W019.959

Appendices

Appendix A: Medical Conditions Associated with Gait and Balance Disorders (PDF, 88KB)

Appendix C: Medications Contributing to the Risk of Falling (PDF, 95KB)

Appendix D:Conducting a Medication Review (PDF, 137KB)

Associated Documents

- Staying Independent Checklist (PDF, 79K)

- Patient Handout: Facts about Falls (PDF, 92KB)

- Checklist for Preventing Falls at Home

- How to Get Up Safely After a Fall

- Patient handout: Tips to Stay Fall Free in Winter (PDF, 98KB)

- 30 Second Chair Stand

- Four Stage Balance Test

- Referral Options Resource Guide for Patients and Caregiver (PDF, 95KB)

- Contributors to Guideline (PDF, 241KB)

Resources

-

Practitioner Resources

-

RACE: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program – www.raceconnect.ca

A phone consultation line for physicians, nurse practitioners and medical residents.

If the relevant specialty area is available through your local RACE line, please contact them first. Contact your local RACE line for the list of available specialty areas. If your local RACE line does not cover the relevant specialty service or there is no local RACE line in your area, or to access Provincial Services, please contact the Vancouver/Providence RACE line.

- Vancouver Coastal Health Region/Providence Health Care: www.raceconnect.ca www.raceapp.ca (tip: download the RACEapp+ to your device from the Apple or Android stores

604-696-2131 (Vancouver) or 1-877-696-2131 (toll free) Available Monday to Friday, 8 am to 5 pm, excluding statutory holidays.

1-877-605-7223 (toll free)

1-844-365-7223 (toll free)

- For Fraser Valley RACE: www.raceapp.ca (tip: download the RACEapp+ to your device from the Apple or Android stores)

- Vancouver Island RACE: to register, please visit www.raceapp.ca (tip: download the RACEapp+ to your device from the Apple or Android stores). For more information, please visit South Island Division of Family Practice: RACE

-

Gov.bc.ca: Fall Prevention

-

Gov.bc.ca: Fall Prevention Resources in BC

-

Pathways

- An online resource that allows GPs and nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. See https://pathwaysbc.ca/login

-

US Centre for Disease Control: Talking about Fall Prevention with Your patients

-

Patient and Caregiver Resources

-

Fraser Health: Your Guide to Independent Living (multilingual)

- HealthLink BC: Preventing Falls in Older Adults

- HealthLink BC: Seniors' Falls Can be Prevented

- HealthLink BC: How to Get Up Safely After a Fall

References

- Liu-Ambrose T, Davis JC, Best JR, Dian L, Madden K, Cook W, et al. Effect of a Home-Based Exercise Program on Subsequent Falls Among Community- Dwelling High-Risk Older Adults After a Fall: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019 04;321(21):2092–100.

- Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018 20;320(19):2020–8.

- Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, Tiedemann A, Michaleff ZA, Howard K, et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 31;1:CD012424.

- Tricco AC, Thomas SM, Veroniki AA, Hamid JS, Cogo E, Strifler L, et al. Comparisons of Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017 07;318(17):1687–99.

- Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, et al. Interventions to Prevent Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018 Apr 24;319(16):1696–704.

- World Health Organization. Falls fact Sheet. 16January2018. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls

- Discharge Abstract Database, Ministry of Health.

- BC Hip Fracture Redesign Project [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://sscbc.ca/projects/bc-redesign-hip-fracture-care

- » The Economic Burden of Injury in BC - BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit. Original value adjusted for 2019 dollars using the Bank of Canada inflation calculator, available at: https://www.injuryresearch.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/BCIRPU-EB-2015.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.injuryresearch.bc.ca/reports/the-economic-burden-of-injury-in-bc-2015/

- Health M of. Vital Statistics Annual Reports [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/life-events/statistics-reports/vital-statistics-annual-reports/2015

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Preventing falls and harm from falls in older people: best practice guidelines for Australian community care. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2009.

- Scott V, Wagar L, Elliot S. Falls & Related Injuries among Older Canadians: Fall-related Hospitalizations & Prevention Initiatives. Prepared on behalf of the Public Health Agency of Canada, Division of Aging and Seniors. 2010. Victoria, BC. Victoria Scott Consulting.

- Nowak A, Hubbard RE. Falls and frailty: lessons from complex systems. J R Soc Med. 2009 Mar;102(3):98–102.

- Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Sep 12;(9):CD007146.

- Moyer VA, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Aug 7;157(3):197–204.

- Health M of. Lifetime Prevention Schedule - Province of British Columbia [Internet]. [cited 2019 May 13]. Available from: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/about-bc-s-health-care-system/health-priorities/lifetime-prevention

- Reducing injuries from falls. - Abstract - Europe PMC [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/18843130

- Scott, V., S. Dukeshire, E. Gallagher & A. Scanlan. A best practice guide for the prevention of falls among seniors living in the community. 2001;

- Anstey KJ, Burns R, von Sanden C, Luszcz MA. Psychological Well-Being Is an Independent Predictor of Falling in an 8-Year Follow-Up of Older Adults. J Gerontol Ser B. 2008 Jul 1;63(4):P249–57.

- Speechley M, Belfry S, Borrie MJ, Jenkyn KB, Crilly R, Gill DP, et al. Risk Factors for Falling among Community-Dwelling Veterans and Their Caregivers. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. 2005 ed;24(3):261–74.

- Fleming J, Matthews FE, Brayne C, Cambridge City over-75s Cohort (CC75C) study collaboration. Falls in advanced old age: recalled falls and prospective follow-up of over-90-year-olds in the Cambridge City over-75s Cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2008 Mar 17;8:6.

- Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing. 2006 Sep;35 Suppl 2:ii37–41.

- Schutzer KA, Graves BS. Barriers and motivations to exercise in older adults. Prev Med. 2004 Nov;39(5):1056–61.

- Ballinger C, Payne S. The construction of the risk of falling among and by older people. Ageing Soc. 2002 May;22(3):305–24.

- Yardley L, Donovan-Hall M, Francis K, Todd C. Older people’s views of advice about falls prevention: a qualitative study. Health Educ Res. 2006 Aug;21(4):508–17.

- Hauer K, Lamb SE, Jorstad EC, Todd C, Becker C, PROFANE-Group. Systematic review of definitions and methods of measuring falls in randomised controlled fall prevention trials. Age Ageing. 2006 Jan;35(1):5–10.

- Shumway-Cook A, Ciol MA, Hoffman J, Dudgeon BJ, Yorkston K, Chan L. Falls in the Medicare population: incidence, associated factors, and impact on health care. Phys Ther. 2009 Apr;89(4):324–32.

- Russell K, Taing D, Roy J. Measurement of Fall Prevention Awareness and Behaviours among Older Adults at Home. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. 2017 Dec;36(4):522–35.

- Medication and falls: risk and optimization. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20934612

- The relations of body composition and adiposity measures to ill health and physical disability in elderly men. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16818465

- Polypharmacy as a risk for fall occurrence in geriatric outpatients. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22212467

- Psychoactive medication use in intermediate-care facility residents. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2903260

- Explicit Criteria for Determining Inappropriate Medication Use in Nursing Home Residents | JAMA Internal Medicine | JAMA Network [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/615518

- 2012 Beers Criteria. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22375952

- American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22376048

- Management of refractive errors. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20385718

- Age-related cataract. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15708105

- Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, pure autonomic failure, and multiple system atrophy | Neurology [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/46/5/1470

- Orthostatic hypotension in the elderly: diagnosis and treatment. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17904451

- Salzman B. Gait and balance disorders in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2010 Jul 1;82(1):61–8.

- Phelan EA, Rillamas-Sun E, Johnson L, LaMonte MJ, Buchner DM, LaCroix AZ, et al. Determinants, circumstances and consequences of injurious falls among older women living in the community. Inj Prev. 2021 Feb 1;27(1):34–41.

- Faes MC, Reelick MF, Banningh LWJ-W, Gier M de, Esselink RA, Rikkert MGO. Qualitative study on the impact of falling in frail older persons and family caregivers: Foundations for an intervention to prevent falls. Aging Ment Health. 2010 Sep 1;14(7):834–42.

- Ringer T, Hazzan AA, Agarwal A, Mutsaers A, Papaioannou A. Relationship between family caregiver burden and physical frailty in older adults without dementia: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017 Mar 14;6(1):55.

- Sadak T, Foster Zdon S, Ishado E, Zaslavsky O, Borson S. Potentially preventable hospitalizations in dementia: family caregiver experiences. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(7):1201–11.

- Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21226685

- Prevention of Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults | NEJM [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp1903252?query=featured_home&page=2

- Phelan EA, Ritchey K. Fall Prevention in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Ann Intern Med. 2018 04;169(11):ITC81–96.

- Bunn F, Dickinson A, Barnett-Page E, Mcinnes E, Horton K. A systematic review of older people’s perceptions of facilitators and barriers to participation in falls-prevention interventions. Ageing Soc. 2008 May;28(4):449–72.

- Vincenzo JL, Patton SK. Older Adults’ Experience With Fall Prevention Recommendations Derived From the STEADI: Health Promot Pract [Internet]. 2019 Jul 27 [cited 2020 Feb 21]; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1524839919861967

- Materials for Healthcare Providers | STEADI - Older Adult Fall Prevention | CDC Injury Center [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/materials.html

- Tricco AC, Thomas SM, Veroniki AA, Hamid JS, Cogo E, Strifler L, et al. Quality improvement strategies to prevent falls in older adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2019 May 1;48(3):337–46.

- Royal College of Physicians. 2012. Older people’s experience of therapeutic exercise as part of a falls prevention service. Patient and public involvement, UK.

- Lee PG, Jackson EA, Richardson CR. Exercise Prescriptions in Older Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Apr 1;95(7):425–32.

- Sherrington C, Michaleff ZA, Fairhall N, Paul SS, Tiedemann A, Whitney J, et al. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Dec;51(24):1750–8.

- Mattle M, Chocano-Bedoya PO, Fischbacher M, Meyer U, Abderhalden LA, Lang W, et al. Association of Dance-Based Mind-Motor Activities With Falls and Physical Function Among Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Sep 1;3(9):e2017688.

- Tremblay MS, Warburton DER, Janssen I, Paterson DH, Latimer AE, Rhodes RE, et al. New Canadian physical activity guidelines. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab Physiol Appl Nutr Metab. 2011 Feb;36(1):36–46; 47–58.

- CSEP | SCPE [Internet]. CSEP | SCPE. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://csepguidelines.ca

- ICD - ICD-9 - International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9.htm

- WHO | ICD-10 online versions [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/icdonlineversions/en/

- Health Quality & Safety Commission | 10 Topics [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 28]. Available from: https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-programmes/reducing-harm-from-falls/10-topics/

- Use of long-term anticoagulation is associated with traumatic intracranial hemorrhage and subsequent mortality in elderly patients hospitalized aft... - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 28]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18073595

- Use of anticoagulation in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who are at risk for falls. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 28]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18334606

- Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of 11 international studies. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 28]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21605729

- Petersen N, König H-H, Hajek A. The link between falls, social isolation and loneliness: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020 May 1;88:104020.

- Schoene D, Wu SM-S, Mikolaizak AS, Menant JC, Smith ST, Delbaere K, et al. Discriminative ability and predictive validity of the timed up and go test in identifying older people who fall: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013 Feb;61(2):202–8.

- Finnegan S, Bruce J, Seers K. What enables older people to continue with their falls prevention exercises? A qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019 15;9(4):e026074.

- Menz HB, Morris ME, Lord SR. Foot and Ankle Risk Factors for Falls in Older People: A Prospective Study. J Gerontol Ser A. 2006 Aug 1;61(8):866–70.

- Juraschek SP, Daya N, Rawlings AM, Appel LJ, Miller ER, Windham BG, et al. Association of History of Dizziness and Long-term Adverse Outcomes With Early vs Later Orthostatic Hypotension Assessment Times in Middle-aged Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Sep;177(9):1316–23.

This draft guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of effective date.

The draft guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee in collaboration with the BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit.

For more information about how BC Guidelines are developed, refer to the GPAC Handbook available at BCGuidelines.ca: GPAC Handbook.

THE GUIDELINES AND PROTOCOLS ADVISORY COMMITTEE

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact Information: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee Email: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Website: www.BCGuidelines.ca Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |

TOP

TOP