Frailty in Older Adults - Early Identification and Management

Effective Date: October 25th, 2017

This guideline was developed over 5 years ago

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Risk Factors

- Epidemiology

- Identification of Patients with Frailty or Vulnerable to Frailty

- Comprehensive Assessment of Patients with Frailty

- Management

- Medication Review

- Advance Care Planning

- Indications for Referral

- Resources

Scope

This guideline addresses the early identification and management of older adults with frailty or vulnerable to frailty. The guideline facilitates individualized assessment and provides a framework and tools to promote patient-centred strategies to manage frailty and prevent further functional decline. The primary focus of the guideline is the community-based primary care setting, although the tools and strategies included may be useful in other care contexts.[A]

[A] For guidance on assessing older adults in the inpatient hospital setting, see Hospital Care for Seniors Clinical Care Management Guideline: 48/6 Model of Care, available at the BC Patient Safety and Quality Council website at: bcpsqc.ca/clinical-improvement/48-6/practice-statements/

Key Recommendations

- See Appendix A: Frailty Assessment and Management Pathway.

- Early identification and management of patients with frailty or vulnerable to frailty provides an opportunity to suggest appropriate preventive and rehabilitative actions (e.g. exercise program, review of diet and nutrition, medication review) to be taken to slow, prevent, or even reverse decline associated with frailty.

- Use a diligent case finding approach to identify patients with frailty, particularly among older adults who regularly or increasingly require health and social services. However, routine frailty screening of the general population of older adults is not recommended.

- Many patients with frailty can be assessed and managed in the primary care setting through a network of support, which may include family, caregivers, and community care providers. Coordinate care with other care providers and ensure patients and caregivers are referred to or connected with local health care and social services.

- For patients with frailty who have multiple health concerns, consider using “rolling” assessments over multiple visits, targeting at least one area of concern at each visit.

- Polypharmacy is common in patients with frailty. Consider the benefits and harms of medications by conducting a medication review in all patients with frailty.

- Develop a care plan using the areas of geriatric assessment outlined in Appendix B: Sample Care Plan Template as a guide. Share the care plan with the patient and/or family/caregivers/representatives, and with other key care providers.

- Initiate advance care planning discussions for patients with frailty or vulnerable to frailty.

Definition

Frailty is broadly seen as a state of increased vulnerability and functional impairment caused by cumulative declines across multiple systems.1–4 Frailty has multiple causes and contributors5 and may be physical, psychological, social, or a combination of these. Frailty may include loss of muscle mass and strength, reduced energy and exercise tolerance, cognitive impairment, and decreased physiological reserve, leading to poor health outcomes and a reduced ability to recover from acute stress.6 Overall, frailty exists on a spectrum.7 While frailty is often chronic and progressive, it is also dynamic and some patients may be able to improve their frail status.8

Risk Factors

With aging, there is a gradual decline in physiological reserve. However, aging is a complex process; evaluation of frailty and its severity is a better indicator of health status than chronological age. Risk factors for frailty include:

|

|

|

Frailty risk and its severity increases with deficit accumulation.9 Physiological reserve may be further decreased by factors such as exacerbation of chronic disease, acute illness, injury, hospitalization, or a change in social supports, leading to increased vulnerability. Consequently, minor stressors may cause a disproportionate change in health status and function.10

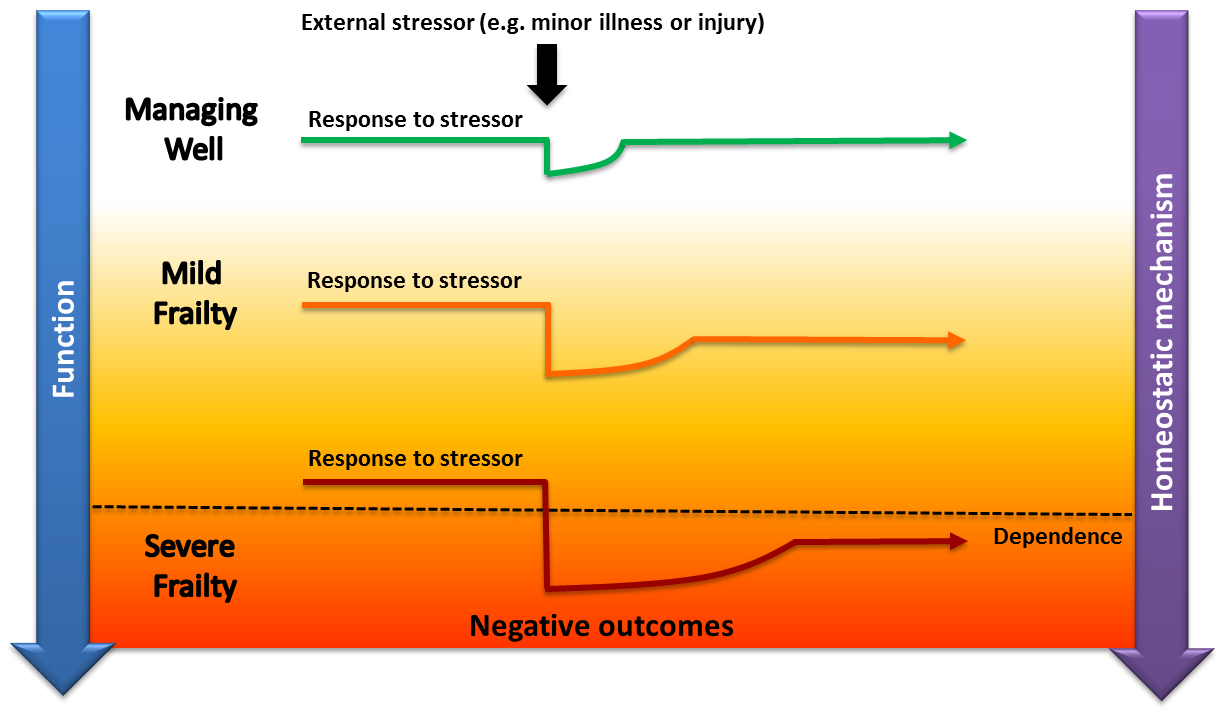

Figure 1: Vulnerability of frail older adults to external stressors

Managing well: A fit older adult who, following a minor stressor, experiences a minor deterioration in function and then returns to homeostasis.

Frailty: A frail older adult who, following a similar stressor, experiences more significant deterioration and does not return to baseline homeostasis. With more severe frailty, this may lead to functional dependency or death.

Adapted from Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet. 2013 Mar;381(9868):752-62 & Lang P-O, Michel J-P, Zekry D. Frailty Syndrome: A Transitional State in a Dynamic Process. Gerontology. 2009;55(5):539-49.

Epidemiology

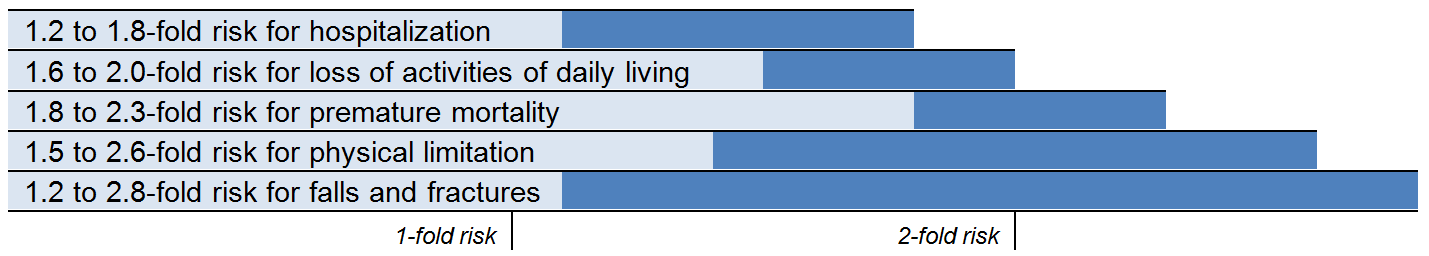

While many adults living in BC remain robust and active as they age, some older adults develop frailty or are vulnerable to frailty. In 2009/10, an estimated 20.4% of British Columbians aged ≥ 65 years living in the community (128,000 people) were frail.4 The prevalence of frailty increases with advanced age (from 16% at ages 65 to 74, to 52% at age 85 and older) and more often affects women than men.4 However, frailty may also be prevalent in younger adults.11 The number of frail older adults in BC will continue to climb as the population ages. Frailty is associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes and higher utilization of health care services.4,12 A recent meta-analysis found that frailty was associated with increased risk for several negative health outcomes, which are listed in Figure 2.13

Figure 2: Increased risk of negative outcomes associated with frailty13

Early identification of patients with frailty or vulnerable to frailty provides an opportunity to suggest appropriate preventive and rehabilitative actions (e.g. exercise program, review of diet and nutrition, medication review) to be taken to slow, prevent, or even reverse decline associated with frailty.8 Although women are generally at higher risk of frailty, they have a better chance of frailty improvement and lower mortality than men.8

Identification of Patients with Frailty or Vulnerable to Frailty

Routine frailty screening of the general population of older adults is not recommended.7 Instead, use a case finding approach to identify patients with frailty, particularly in older adults who regularly or increasingly require health and social services (e.g. emergency room visits, ambulance crew attendance, adult day clinics, hospitalization, home support, referral to residential care).7 Encounters with health and social care professionals present an opportunity to identify older adults with frailty or vulnerable to frailty and take steps to reduce or manage associated risks.7,14–18

Signs and Symptoms

Use a diligent case finding approach to identify warning signs of frailty. Older adults may have a number of non-specific concerns that may suggest frailty or vulnerability to frailty. In addition to the review of chronic conditions, some other areas to assess are noted in Table 1 below. Observed changes or concerns expressed in these areas may be early warning signs of frailty, while a combination of impairments may signal progression towards frailty.There are certain signs and symptoms (e.g. falls, delirium, immobility) that may raise a higher level of suspicion that the patient has frailty7 – see Table 1. However, these problems may have causes other than frailty, so it is important to conduct a further review.

Table 1: Possible warning signs of frailty1,7,15,19,20

Signs indicated with bold * may raise a higher level of suspicion of frailty.

|

Medical:

Psychological:

|

Functional:

Medications and alcohol:

Social and environmental:

|

Frailty Scoring Tools

Patients with more severe frailty or certain geriatric syndromes may be easily identified. However, identifying mild or early stage frailty may require a formal assessment – consider confirming clinical suspicion of frailty with a scoring tool.

Dozens of different frailty measures have been developed over the years, but there is no single measure that is viewed as the gold standard21 and many are not well adapted for the busy primary care setting.22 The tools in Table 2 are recommended for community-based primary care.23

Table 2: Recommended frailty scoring tools for community-based primary care

|

|

Tool |

Frailty suggested by: |

These tests, including scoring information, are available in the Associated Documents section below. |

|

General |

Score ≥ 37 |

||

|

Mobility |

Time > 5 seconds over 4m7 |

||

|

Time > 10 seconds7 |

|||

|

Cognitive Impairment |

See Guidelines.ca: Cognitive Impairment - Recognition, Diagnosis and Management in Primary Care |

||

|

Other tests, as appropriate |

Any one of the above tools may suggest frailty. Cognition and mobility tests are best done in the outpatient setting when patients are at their clinical baseline.

Comprehensive Assessment of Patients with Frailty

Patients with identified frailty require additional assessment to support the development or refinement of a care plan. The gold standard for assessing and managing frailty in older adults is comprehensive geriatric assessment:7 an interdisciplinary process that evaluates medical, psychological, social and functional domains of older adults with frailty to develop a detailed care plan for treatment, support and follow-up.24 However, comprehensive geriatric assessment by medical specialists in geriatric care is resource intensive – see Indications for Referral below.

Many patients with frailty can be assessed and managed in the primary care setting through a network of support, which may include family, caregivers, and community care providers. Ensure patients and caregivers are referred to or connected with local health care and social services, such as those available to eligible patients through Home and Community Care within local health authorities.

Areas of Assessment

There are number of common problems associated with frailty such as falls, weight loss, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, cognitive impairment and polypharmacy—many of which may be reversible or preventable—that should be addressed to improve outcomes.

Conduct a review of the medical, functional, psychological and social/environmental needs of the patient.7 The areas of geriatric assessment outlined in Table 3 in the Management section below and the Appendix B: Sample Care Plan Template may help guide assessment.

For patients with frailty who have multiple health concerns, consider using “rolling” assessments over multiple visits, targeting at least one area of concern at each visit.25

Family physicians may be eligible for Complex Care incentive fees, which offer additional compensation to family physicians for the management of patients with complex conditions, including moderate or severe frailty, or for Chronic Disease Management incentive fees. See the Resources section below and www.gpscbc.ca: Billing Guides.

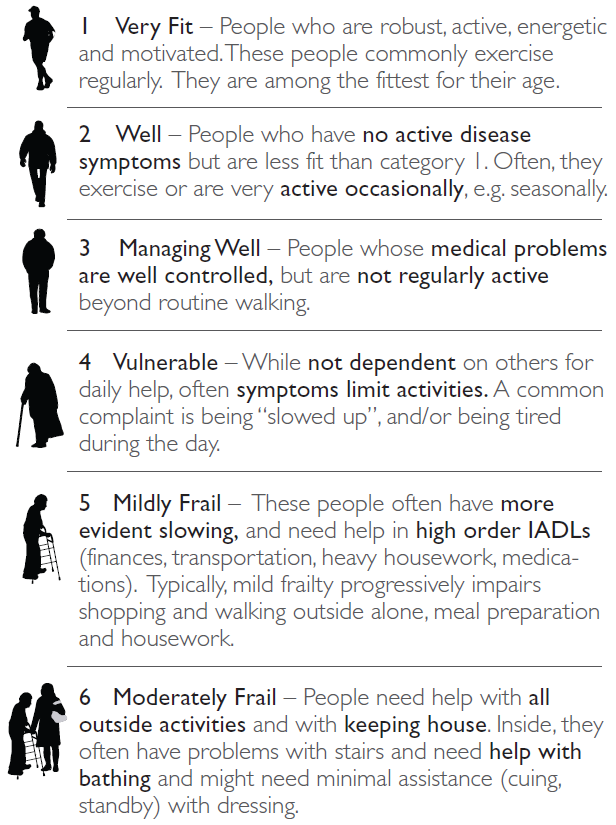

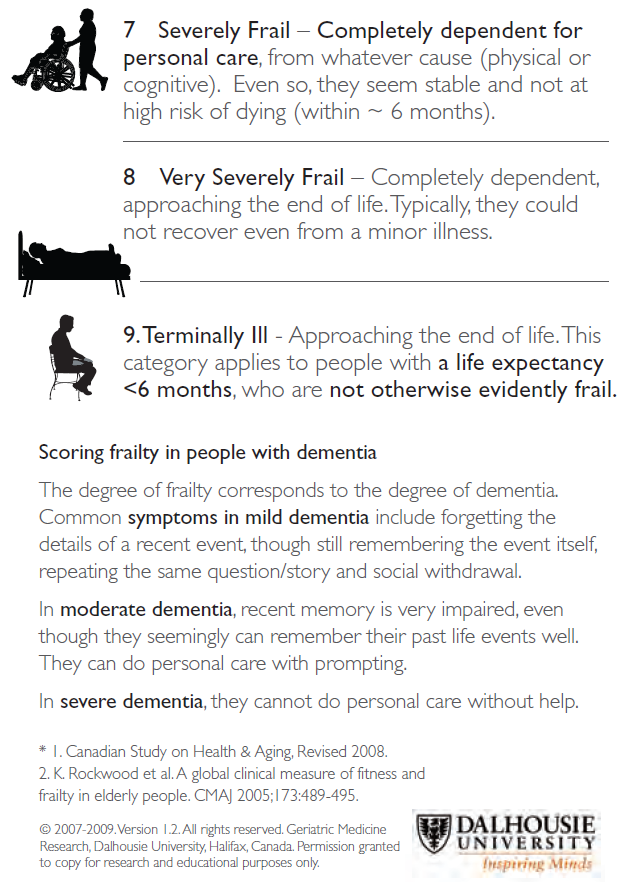

Grading Severity of Frailty

Once a patient is identified as frail or vulnerable to frailty, it is recommended that the Clinical Frailty Scale be used to categorize the needs of the patient. The Clinical Frailty Scale is a validated tool that uses clinical information to stratify patients with frailty based on their level of vulnerability. The Clinical Frailty Scale is a strong predictor of institutionalization and mortality2 and is useful for consistently communicating frailty status between care providers.

Figure 3: Clinical Frailty Scale2

A PDF of Figure 3 is available at https://www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-tools/clinical-frailty-scale.html. See also the PATH Frailty App based on the Frailty Assessment for Care Planning Tool (FACT) - https://pathclinic.ca/app/.

Management

Use the areas of geriatric assessment outlined in Table 3 below and in Appendix B: Sample Care Plan Template as a guide in developing a care plan.

The care plan is intended to be developed over a series of planned office visits with one or more areas of concern addressed at each appointment.

Review and document goals and strategies to address each area of concern. Consider relevant evidence available regarding

- important outcomes;

- patient trajectory and prognosis;

- interactions within/among treatments and conditions; and

- benefits and harms of care plan components.26

When possible, work with other care providers as an interdisciplinary team and establish clear roles and duties. Physicians may be eligible for Patient Conferencing fees for case conferencing with other health care providers – see www.gpscbc.ca: Patient Conferencing Fee Initiative.

Approach to Care Plan Development

1) Inquire about the patient’s primary concerns

Also consider the concerns of family, caregivers and representatives, as appropriate.26

2) Review patient goals of care, values and preferences26

The care plan should be developed jointly with the patient and/or the patient representative, as appropriate, to establish a shared understanding of desired care.14

The care plan should address:

- individualized goals associated with significant health and safety risks;27

- plans to manage significant comorbidities in relation to patient goals;28

- appropriate prevention activities for the patient;29 and

- self-management support for the patient and family/caregiver(s).

Identify patients who would benefit from palliative care early in the illness trajectory: a palliative approach addresses the need for pain and symptom management, as well as psychosocial and spiritual support.

3) Review history, current medical conditions, and interventions

Frailty can mask or mimic other illness, so it is essential to determine whether the limitation the patient is experiencing results from frailty or a comorbid condition.

- Review signs and symptoms and conduct investigations for differential diagnoses, as appropriate.

- Review weight, diet and food intake, and level of physical activity.

Consider patient adherence and comfort with past/current treatment plans.26 Note that treatment guidelines and prescribing recommendations developed for more robust adults are often inappropriate for older adults with frailty.

4) Consider conducting a medication review

Polypharmacy is common in patients with frailty. Consider the benefits and harms of medications by conducting a medication review in patients with frailty– see Appendix C: Medication Review and the Medication Review section below. Medication reviews can decrease the number of drug-related problems and adverse drug reactions.30,31 The process helps prioritize the patient’s goals of care, eliminate unnecessary drugs, add needed drugs, and review monitoring requirements.

5) Initiate advance care planning discussions – see the Advance Care Planning section.

6) Communicate the care plan

Communication for coordination and continuity of care is particularly important for older adults with frailty.28 The care plan should include the names and contact information of key care providers (e.g. community support team, case manager, specialists, allied health professionals) and should be shared with key care providers. Give a copy of the care plan to the patient and/or family/caregivers/representatives to carry as they become involved with other health care providers and as they transition across care settings.

7) Reassess the care plan at selected intervals

Identify an appropriate time frame to re-evaluate the care plan. Consider benefit, feasibility, adherence, and alignment with patient goals, values and preferences.26

Provide the patient or caregiver with a copy of the Associated Document: Resource Guide for Older Adults and Caregivers.

Table 3: Areas of geriatric assessment24,32

This table is offered as a guide for areas of assessment to consider.

|

AREAS OF ASSESSMENT |

RECOMMENDATIONS AND RESOURCES |

||

|

Medical Review |

|||

|

Immunizations |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Habits |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Nutrition |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Bowel and Bladder |

|

||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

Perception and Communication |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Pain |

|||

|

Psychological Review |

|||

|

Cognition |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|||

|

Mood |

|||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Functional Review |

|||

|

Mobility |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Fall Risk |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Physical Activity |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Basic Activities of Daily Living |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Social and Environmental Review |

|||

|

Social and Spiritual Needs |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Care Support |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Managing at Home |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

Medication Review

People aged ≥ 65 years represent the largest consumers of medications and consequently, experience the highest rate of adverse drug events. A 2012 Canadian study showed that 27% of seniors take five or more regular medications, with almost half experiencing an adverse reaction that required medical intervention.34

Based on clinical judgement, review for potentially inappropriate medications and consider medication reduction and/or simplifying the medication regimen. For information and resources on conducting a medication review, see Appendix C: Medication Review.

Medication reviews should be considered when a patient:

- has one or more chronic diseases;

- has a drug therapy problem or is on high risk drugs (e.g. opioids, antipsychotics);

- is on medications that are inconsistent with goals of care;

- has been recently discharged from hospital or had a significant change in health status;

- has multiple prescribers; or

- takes medications that require laboratory monitoring.

Consider requesting a medication review by a pharmacist. Community pharmacists are trained in conducting medication reviews. The patient’s regular pharmacist may be able to conduct a medication review if requested. Medication reviews by a pharmacist are covered by BC Pharmacare for eligible patients – see gov.bc.ca: PharmaCare Policy Manual.

Compile a complete record of drugs that the patient is taking, including any over-the-counter drugs and natural health products – see Associated Documents: Best Possible Medication History. Give a dated copy of the medication record to the patient and/or family/caregivers/representatives, as appropriate.

Consider setting up your medical practice to have access to PharmaNet.[*] To learn more or to register, see www2.gov.bc.ca: Community Health Practice Access to PharmaNet.

[*] PharmaNet is an online database that captures all outpatient prescriptions for drugs and medical devices dispensed in BC. Community Health Practice Access to PharmaNet is available to all physicians and nurse practitioners licensed to practice in BC.

Advance Care Planning

Advance care planning involves conversations with the patient about their values and goals related to health care and the quality of they may be able to achieve with treatment alternatives. Advance care planning should be tailored to the needs of the patient along the disease trajectory. Advance care planning conversations should be documented in the care plan and include the identification of substitute decision makers.

- See the Associated Document: Advance Care Planning Resource Guide for Patients and Caregivers or the Ministry of Health’s advance care planning guide My Voice – Expressing My Wishes for Future Health Care Treatment, available at www.gov.bc.ca/advancecare.

Depending on the patient’s values and goals, health care providers should consider the need for the following documentation:

- No Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (No CPR) form: Order that no CPR be provided by health care providers and first responders. For more information or to access the No CPR form, see HealthLinkBC.ca: No CPR Form.

- Medical Order for Scope of Treatment (MOST): A patient’s code status and scope of treatment can also be recorded in a MOST form. MOST forms are specific to each health authority and health care providers should refer to the policy and protocols of their health authority governing their use. Contact your local health authority for more information, or see HealthlinkBC.ca: Advance Care Planning.

Indications for Referral

Home and Community Care

Primary care practitioners play an essential role in identifying patients in need of increased supports and facilitating intake into the system of care support. Ensure patients and caregivers in need of support are referred to local health care and social services, which are available from both publicly subsidized and private pay providers.

- For help finding information on social and health resources in your local community, see BC211 at www.bc211.ca, or where available, see Fetch (For Everything That's Community Health) at https://divisionsbc.ca/provincial/what-we-do/patient-support/fetch.

- Provide the patient or caregiver with a copy of the Associated Document: Resource Guide for Older Adults and Caregivers.

Case managed services available to eligible patients through Home and Community Care within local health authorities include:

- community nursing for acute, chronic, palliative or rehabilitative support;

- community rehabilitation by licensed physical and occupational therapists;

- adult day services for personal care, health care and social and recreational activities;

- home support for assistance with activities of daily living;

- caregiver respite and relief;

- assisted living and residential care; and

- end-of-life care services.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Patients with frailty who have multiple complex needs, diagnostic uncertainty or challenging symptom control may benefit from a referral to comprehensive geriatric assessment by geriatric medicine specialists or trained family physicians.7

- Physicians and nurse practitioners can contact the Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise (RACE) phone line to speak directly with a specialist, including geriatricians, or can access referral to a geriatric clinic through PathwaysBC.ca. Refer to the Resources section below.

Palliative Care

A palliative approach is needed for patients living with active, progressive, life-limiting illnesses who need pain and symptom management and support around functional or psychosocial issues, have care needs that would benefit from a coordinated or collaborative care approach, and/or have frequent emergency room visits. Assess where patients are in their illness trajectory, functional status, and symptom burden.

For more information, see www2.gov.bc.ca: Home and Community Care or contact your local health authority.

Resources

RACE: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program – www.raceconnect.ca

A telephone consultation line for select specialty services for physicians, nurse practitioners and medical residents.

If the relevant specialty area is available through your local RACE line, please contact them first. Contact your local RACE line for the list of available specialty areas. If your local RACE line does not cover the relevant specialty service or there is no local RACE line in your area, or to access Provincial Services, please contact the Vancouver/Providence RACE line.

- Vancouver Coastal Health Region/Providence Health Care: www.raceconnect.ca

- ( 604-696-2131 (Vancouver) or 1-877-696-2131 (toll free) Available Monday to Friday, 8 am to 5 pm

- Northern RACE: ( 1-877-605-7223 (toll free)

- Kootenay Boundary RACE: www.divisionsbc.ca/kb/race ( 1-844-365-7223 (toll free)

- For Fraser Valley RACE: www.raceapp.ca (download at Apple and Android stores)

- South Island RACE: www.raceapp.ca (download at Apple and Android stores) or see www.divisionsbc.ca/south-island/RACE

Pathways – PathwaysBC.ca

An online resource that allows GPs and nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. In addition, Pathways makes available hundreds of patient and physician resources that are categorized and searchable.

General Practice Services Committee – www.gpscbc.ca

- Practice Support Program: offers focused, accredited training sessions for BC physicians to help them improve practice efficiency and support enhanced patient care.

- Chronic Disease Management and Complex Care Incentives: compensates GPs for the time and skill needed to work with patients with complex conditions or specific chronic diseases.

References

- Fried LP. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci [Internet]. 2001;56. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146

- Rockwood K. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Can Med Assoc J. 2005 Aug 30;173(5):489–95.

- Puts MTE, Toubasi S, Atkinson E, Ayala AP, Andrew M, Ashe MC, et al. Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a protocol for a scoping review of the literature and international policies. BMJ Open. 2016 Mar 1;6(3):e010959.

- Hoover M, Rotermann M, Sanmartin C, Bernier J. Validation of an index to estimate the prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling seniors. Health Rep. 2013 Sep;24(9):10–7.

- Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013 Jun;14(6):392–7.

- Espinoza SE, Fried LP. Risk Factors for Frailty in the Older Adult. Clin Geriatr. 2007 Jun;15(6):37–44.

- British Geriatrics Society. Fit for Frailty Consensus best practice guidance for the care of older people living with frailty in community and outpatient settings [Internet]. 2014 Jun. Available from: http://www.bgs.org.uk/campaigns/fff/fff_full.pdf

- Trevisan C, Veronese N, Maggi S, Baggio G, Toffanello ED, Zambon S, et al. Factors Influencing Transitions Between Frailty States in Elderly Adults: The Progetto Veneto Anziani Longitudinal Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Jan;65(1):179–84.

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. The Lancet. 2013 Mar;381(9868):752–62.

- Clegg A. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet [Internet]. 2013;381. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

- Kehler DS, Ferguson T, Stammers AN, Bohm C, Arora RC, Duhamel TA, et al. Prevalence of frailty in Canadians 18–79 years old in the Canadian Health Measures Survey. BMC Geriatr [Internet]. 2017 Dec [cited 2017 Aug 1];17(1). Available from: http://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-017-0423-6

- Cesari M, Prince M, Thiyagarajan JA, De Carvalho IA, Bernabei R, Chan P, et al. Frailty: An Emerging Public Health Priority. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016 Mar 1;17(3):188–92.

- Vermeiren S, Vella-Azzopardi R, Beckwée D, Habbig A-K, Scafoglieri A, Jansen B, et al. Frailty and the Prediction of Negative Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016 Dec;17(12):1163.e1-1163.e17.

- Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004 Feb 1;116(3):179–85.

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004 Mar;59(3):255–63.

- Béland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Dallaire L, Fletcher J, Contandriopoulos A-P, et al. Integrated services for frail elders (SIPA): a trial of a model for Canada. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. 2006;25(1):5–42.

- Kramer BJ, Auer C. Challenges to providing end-of-life care to low-income elders with advanced chronic disease: lessons learned from a model program. The Gerontologist. 2005 Oct;45(5):651–60.

- Stock RD, Reece D, Cesario L. Developing a comprehensive interdisciplinary senior healthcare practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 Dec;52(12):2128–33.

- Bergman H, Béland F, Karunananthan S, Hummel S, Hogan D, Wolfson C. Développement d’un cadre de travail pour comprendre et étudier la fragilité: Pour l’initiative canadienne sur la fragilité et le vieillissement. Gérontologie Société. 2004;109(2):15.

- Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions Between Frailty States Among Community-Living Older Persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Feb 27;166(4):418.

- Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M, Sabia S, Fransson EI, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Measures of frailty in population-based studies: an overview. BMC Geriatr [Internet]. 2013 Dec [cited 2017 Feb 1];13(1). Available from: http://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2318-13-64

- Hoogendijk EO, van der Horst HE, Deeg DJH, Frijters DHM, Prins BAH, Jansen APD, et al. The identification of frail older adults in primary care: comparing the accuracy of five simple instruments. Age Ageing. 2013 Mar 1;42(2):262–5.

- Turner G, Clegg A. Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British Geriatrics Society, Age UK and Royal College of General Practitioners report. Age Ageing. 2014 Nov 1;43(6):744–7.

- Ramani L, Furmedge DS, Reddy SP. Comprehensive geriatric assessment. Br J Hosp Med Lond Engl 2005. 2014 Aug;75 Suppl 8:C122-125.

- Elsawy B, Higgins KE. The geriatric assessment. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Jan 1;83(1):48–56.

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Patient-Centered Care for Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Stepwise Approach from the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012 Oct;60(10):1957–68.

- Durso SC. Using clinical guidelines designed for older adults with diabetes mellitus and complex health status. JAMA. 2006 Apr 26;295(16):1935–40.

- Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007 Feb 28;297(8):831–41.

- Petrone K, Katz P. Approaches to appropriate drug prescribing for the older adult. Prim Care. 2005 Sep;32(3):755–75.

- Huiskes VJB, Burger DM, van den Ende CHM, van den Bemt BJF. Effectiveness of medication review: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Fam Pract [Internet]. 2017 Dec [cited 2017 Apr 12];18(1). Available from: http://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-016-0577-x

- Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Sudhakaran S, Kirkpatrick CM, Dooley MJ, Ryan-Atwood TE, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in community settings: An overview of systematic reviews. Res Soc Adm Pharm [Internet]. 2016 Aug [cited 2017 May 11]; Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S155174111630362X

- Comprehensive Assessment of the Frail Older Patient - British Geriatrics Society [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jan 27]. Available from: https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/resource-series/comprehensive-geriatric-assessment-toolkit-for-primary-care-practitioners

- Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, Cesari M, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Morley JE, et al. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Optimal Dietary Protein Intake in Older People: A Position Paper From the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013 Aug;14(8):542–59.

- Reason B, Terner M, Moses McKeag A, Tipper B, Webster G. The impact of polypharmacy on the health of Canadian seniors. Fam Pract. 2012 Aug 1;29(4):427–32.

Appendices

- Appendix A - Frailty Assessment and Management Pathway (PDF, 123KB)

- Appendix B - Sample Care Plan Template (PDF, 525KB)

- Appendix C - Medication Review (PDF, 276KB)

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline

- PRISMA-7 Questionnaire (PDF, 146KB)

- Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test (PDF, 154KB)

- Gait Speed Test (PDF, 148KB)

- Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (PDF, 685KB)

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (external website)

- Best Possible Medication History (Word Document, 282KB)

- Resource Guide for Older Adults and Caregivers (PDF, 296KB)

- Advance Care Planning Resource Guide (PDF, 165KB)

- Contributors to Guideline (PDF, 103KB)

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, approved by the British Columbia Medical Association and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

|

Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the "Guidelines") have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problems. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional.

TOP

TOP