Concussion / Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI)

Effective Date: September 19, 2024

Revised: May 21, 2025 [Minor revisions to replace Appendices A-C with updated Concussion Awareness Training Tool (CATT) resources.]

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Etiology

- Epidemiology

- Prognosis and Risk Factors for Persisting Symptoms

- Management

- Follow-Up

- Special Considerations for Children, Older Adults, and Certain Populations

- Controversies in Care

- Resources

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for the primary care assessment, diagnosis, and management of concussion/mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) for patients of all ages. This guideline is not appropriate for use with moderate or severe brain injuries.

Key Recommendations

Assessment and Diagnosis

- Assess all individuals suspected of concussion as soon as possible, ideally within 72 hours, and before potential re-exposure to head trauma.

- Triage patients with red flags for emergency department evaluation.

- Screen patients to identify those at risk of persisting symptoms.

- Routine neuroimaging is not recommended unless specific red flags are present.

- Evaluate patients for other relevant conditions (e.g., mental health or mood disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), chronic headache, substance use). Manage these while also treating for concussion.

Management

- Counsel all patients to observe relative rest for 24-48 hours.

- Reassure patients of likelihood of good prognosis but highlight importance of early recognition and management of persisting symptoms.

- Advise patients that they can gradually return to activities even in the presence of mild symptoms. This should be at a pace with no more than mild and brief symptom exacerbation.

- Advise patients to avoid activities that risk reoccurrence of head trauma until medical readiness has been determined.

- Prescribe aerobic exercise interventions to decrease concussion-related symptoms and reduce the risk of persistent symptoms. Begin with 55% max heart rate then progress to 70%.

- Focus early management strategies on 1) headache, 2) sleep, and 3) mood.

- Conduct a follow-up assessment, ideally within two weeks of diagnosis.

- Refer patients at risk of or experiencing persisting symptoms to interdisciplinary care.

- Provide patient education in verbal and written formats.

- Where possible, co-manage patients <5 years old with persisting symptoms with a pediatrician.

Special Considerations

- Consider interpersonal violence and child abuse/neglect with trauma-related presentations. Report and refer as required.

- Consider specialist involvement to assess/manage patients with neurological conditions or injuries (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury).

- Maintain a high index of suspicion for mental health sequelae, screen and manage appropriately.

Definition

A concussion is a type of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) caused by a direct or indirect external force that results in acceleration of the brain within the skull.1,2 Concussion may or may not include a brief loss of consciousness (LOC).2 Concussion results in acute or delayed onset (<72 hours) of neurological impairment that generally resolves spontaneously.2,3 Standard neuroimaging is not clinically indicated but if done, is normal.2

While all concussions are mTBIs, not all mTBIs are concussions. mTBI is a broader category that includes injuries with a similar clinical presentation, but with abnormal neuroimaging. For the purposes of this document, the term concussion is used throughout as outpatient management is the same.

Etiology

Concussions are not specific to sporting environments. While falls are the most common cause across all ages4, concussion can also result from motor vehicle or bicycle collisions, assault (including interpersonal violence), military combat, blast/explosions, work-related incidents, etc.3

Epidemiology

In 2019/20, approximately 19,000 British Columbians visited the emergency department for concussion.5 These figures likely under-report injury incidence because many either do not seek medical assessment or are seen in community-based clinics.5 Children aged 0-14 years have the highest rate of emergency department visits for concussion.5 Older adults also have high concussion rates that are influenced by general frailty and age-specific risk factors for falls (e.g., cognitive impairment, polypharmacy, reduced physical fitness).6

Prognosis and Risk Factors for Persisting Symptoms

Prognosis is generally good, with most experiencing symptom resolution within a few weeks3 to months7. However, symptom resolution does not necessarily indicate complete physiological recovery and subtle deficits that are not measurable through subjective assessments may persist.8 Patients are at increased risk of re-injury during the recovery period, even if they are asymptomatic. Re-injury before complete recovery can result in more severe and longer-lasting physiological/clinical disturbances.8

While most patients recover well, one in four youth9 and at least one in six adults have persisting symptoms (i.e., those that remain >4 weeks) and concussion-related disability.7 High initial symptom severity is the strongest, most reliable predictor of persisting symptoms. Refer to the Initial Medical Assessment section for other examples.

Initial Medical Assessment

Assess all individuals suspected of concussion as soon as possible, ideally within 72 hours, and before potential re-exposure to head trauma. The purpose of the initial assessment is to:

- Rule out serious injury,

- Confirm a diagnosis, and

- Provide patient education and direct early management.

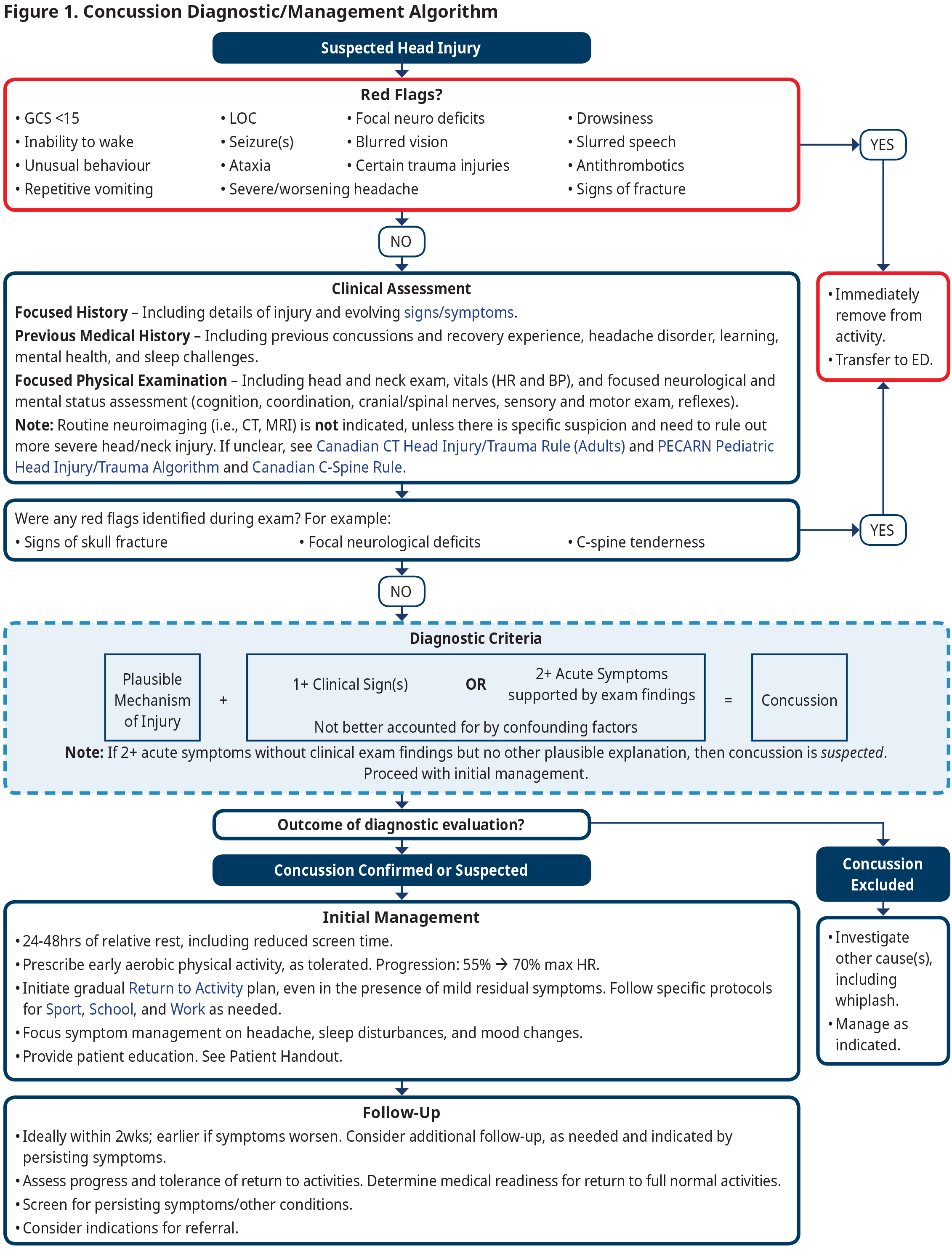

See Figure 1: Concussion Diagnostic/Management Algorithm. Tailor the assessment based on time elapsed since injury and clinical judgment. Note that patients may have diminished concentration and tolerance for a lengthy assessment as well as impaired recall for education/instruction. Some patients involved in higher risk contact sports may be asked to undergo a pre-injury examination to document their healthy baseline status. However, such examinations are not recommended as standard practice in BC primary care settings.

Standardized assessment forms are available to document, organize, and compare initial post-injury and serial concussion assessments. However, the reality of practitioner time and availability may make lengthy assessments challenging to complete in the primary care setting. The information in this guideline represents a condensed version of these standardized assessments, based on the clinical expertise of the working group.

- Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE)

- <72 hours – Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT). See Adult SCAT6 and Child SCAT6.

- >72 hours – Sport Concussion Office Assessment Tool (SCOAT). See Adult SCOAT6 and Child SCOAT6.

1. Rule out Serious Injury

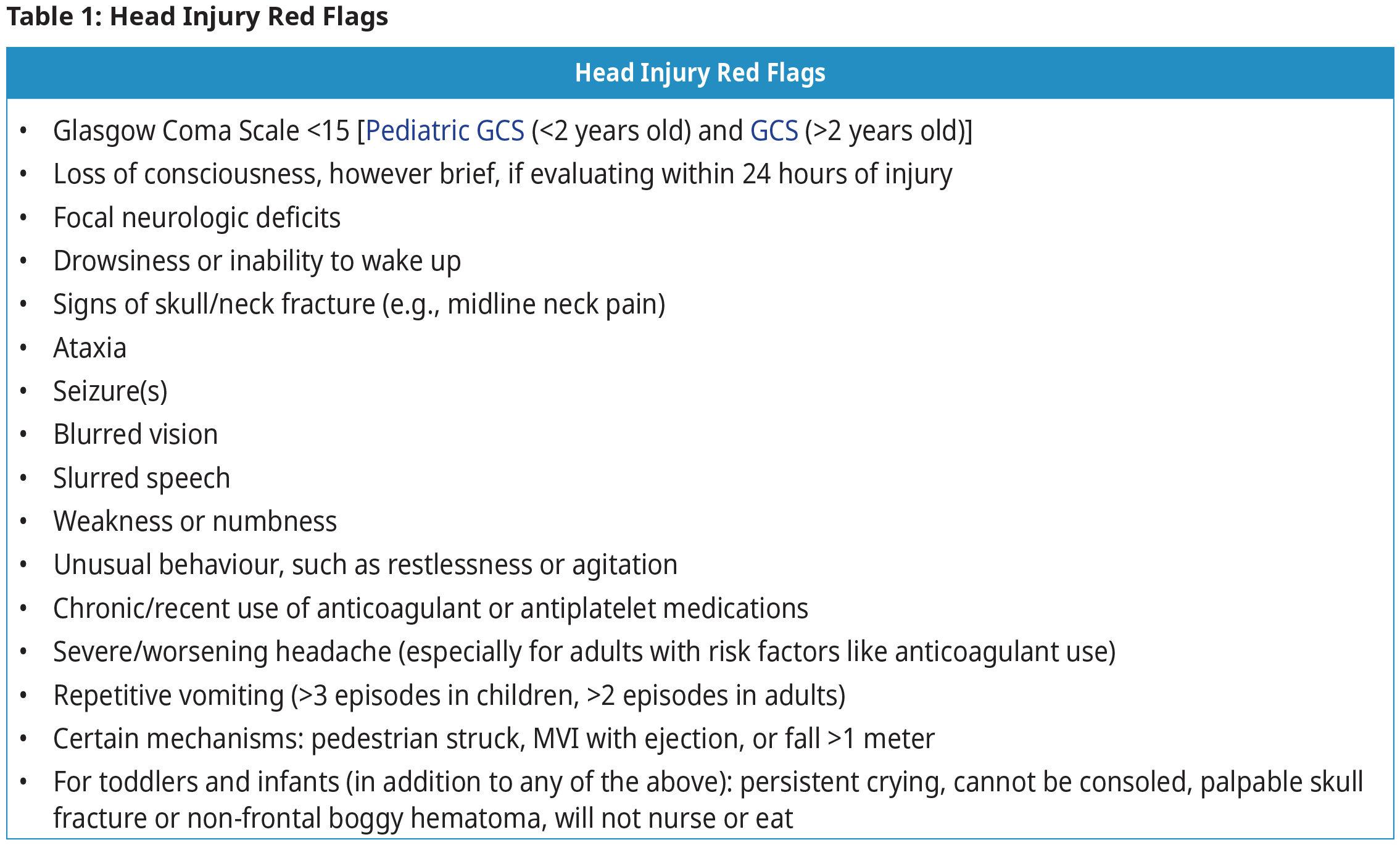

The presence of head injury red flags (Table 1: Head Injury Red Flags) requires referral to the emergency department for further investigation and management.

2. Confirm a Diagnosis

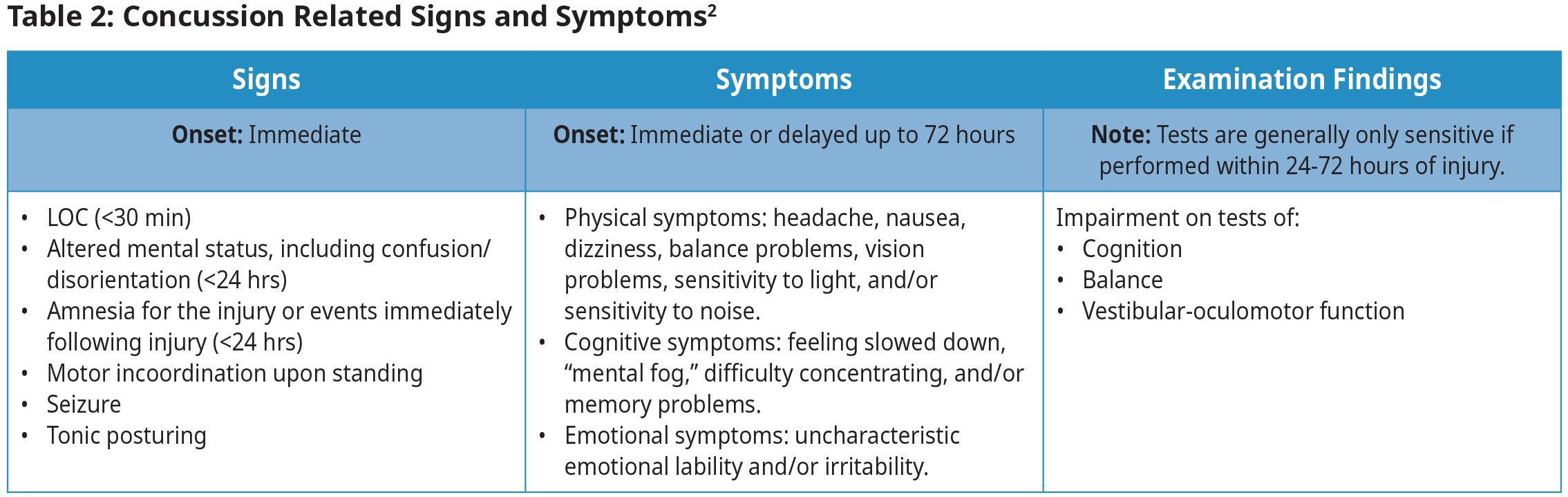

Concussion is a clinical diagnosis that requires a plausible mechanism of injury, and acute clinical signs, or symptoms with exam findings.2 See Table 2: Concussion Related Signs and Symptoms for more detailed diagnostic criteria information. Differential diagnosis should consider potential confounding factors, including pre-existing and co-occurring health conditions that can mimic signs and symptoms of concussion.11

Diagnosis may be complicated because concussion signs and symptoms are often non-specific, and can be concussion-related, pre-existing, or both.1 For example, an individual with a previous history of headaches may experience exacerbation of those headaches following concussion. A further challenge is that clinical signs, if present immediately following the impact, are typically transient, resolving before the first primary care visit. If not clearly documented in acute care medical records, clinical signs can be assessed retrospectively by asking the patient or witnesses for details about the injury event.

Clinical History

- Determine whether there was a plausible mechanism of injury.

- Assess signs and symptoms, including their severity.

- Consider using validated tools for this assessment. The Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ)12 is helpful in establishing an initial list/severity of concussion related symptoms and serially assessing them throughout the management period.

- Assessing initial symptom severity can identify patients who may warrant closer monitoring given that this is the greatest predictor of persisting symptoms.

- If present, clarify details on onset of neurological impairment, including LOC and/or amnesia.

- Screen for risk of persisting symptoms by identifying significant/relevant medical history, including the following: 4,8,13–17

- Pre-injury history of:

- Concussion with persistent symptoms

- Migraine

- Psychiatric history (e.g., depression, anxiety)

- Sleeping problems

- Learning disabilities, including ADHD

- Post-injury experience of:

- Highly symptomatic [strongest, most reliable predictor]

- Negative recovery expectations

- Psychological distress, including new onset depression and anxiety

- Whiplash

- CT abnormalities (Note: Routine imaging is not indicated, unless specific red flags are present. If done, abnormal CT result is associated with persisting symptoms.)

- For older adults: High post-injury scores of neck pain, irritability, and forgetfulness

- Sex (female at greater risk)

- Age (younger patients and older adults at greater risk)

- Pre-injury history of:

Physical Examination

Conduct a focused examination based on the mechanism of injury and clinical judgment. Include:

- Head and neck exam, including ruling out c-spine point tenderness.

- Focused neurologic and mental status exam, which may include:

- Cognition (e.g., word recall and counting digits backwards)

- Coordination, gait, and balance (e.g., simple tandem gait, tandem gait with cognitive task).

- Cranial and spinal nerves, including visual system (e.g., pupils, vestibular ocular reflex)

- Sensory and motor exam

- Reflexes

- Heart rate and blood pressure, taken after 2 min supine and then after 1 min standing.1

Investigations

Routine neuroimaging (i.e., CT, MRI) is not indicated, unless there is specific suspicion and need to rule out more severe head/neck injury. If unclear, the following validated tools can help determine injury severity and need for imaging. Refer to BC Guidelines: Appropriate Imaging for Common Situations in Primary and Emergency Care and BC Guidelines: Computed Tomography (CT) Prioritization.

- The PECARN Pediatric Head Injury/Trauma Algorithm to rule out the presence of clinically important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI) in patients <18 years old with GCS >14.

- The Canadian CT Head Injury/Trauma Rule to rule out the presence of intracranial injuries requiring neurosurgical intervention without CT in patients >16 years old with GCS 13-15.

- The Canadian C-Spine Rule to rule out the presence of cervical spine injury in alert, stable patients >16 years old without radiographic imaging.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and electroencephalogram (EEG) are not recommended unless there is a high index of suspicion for cardiac factors or a seizure disorder.

While common in research settings, advanced neuroimaging, fluid-based biomarkers, and genetic testing are not indicated for a standard clinical concussion assessment.1

3. Provide Patient Education and Direct Early Management

- Provide education verbally and in written format at all visits.

- Reassure patients that prognosis is usually good and most recover within a few weeks.

- Educate patients about the nature of their injury, the increased risk of subsequent injury, how to improve recovery, and how to identify persisting symptoms.

- Refer to Appendix D – Patient Education Handout (PDF, 258KB) for a comprehensive patient handout and to BC’s Concussion Awareness Training Tool (CATT) for documentation (e.g., Medical Assessment Letter).

Management

Early and active management is associated with improved outcomes while prolonged periods of rest may hinder concussion recovery.18,19 It is important that patients avoid activities that risk reoccurrence of head trauma until medical readiness has been determined. Prescribe aerobic exercise interventions to decrease concussion-related symptoms and reduce the risk of persistent symptoms.20 Prioritizing hydration, regular meals with balanced nutrition, and good sleep is also important during the recovery period.

For the first 24-48 hours, patients should:

- Observe relative physical/cognitive rest, including minimizing screen time and not driving.21,22

- Monitor for new or worsening symptoms and report back to primary care or emergency department, as appropriate. See Table 1: Head Injury Red Flags.

- Maintain light physical activity (e.g., slow walks), as long as there is no more than mild and brief exacerbation of symptoms (i.e., <2 point increase in symptom severity score for <1 hour).23

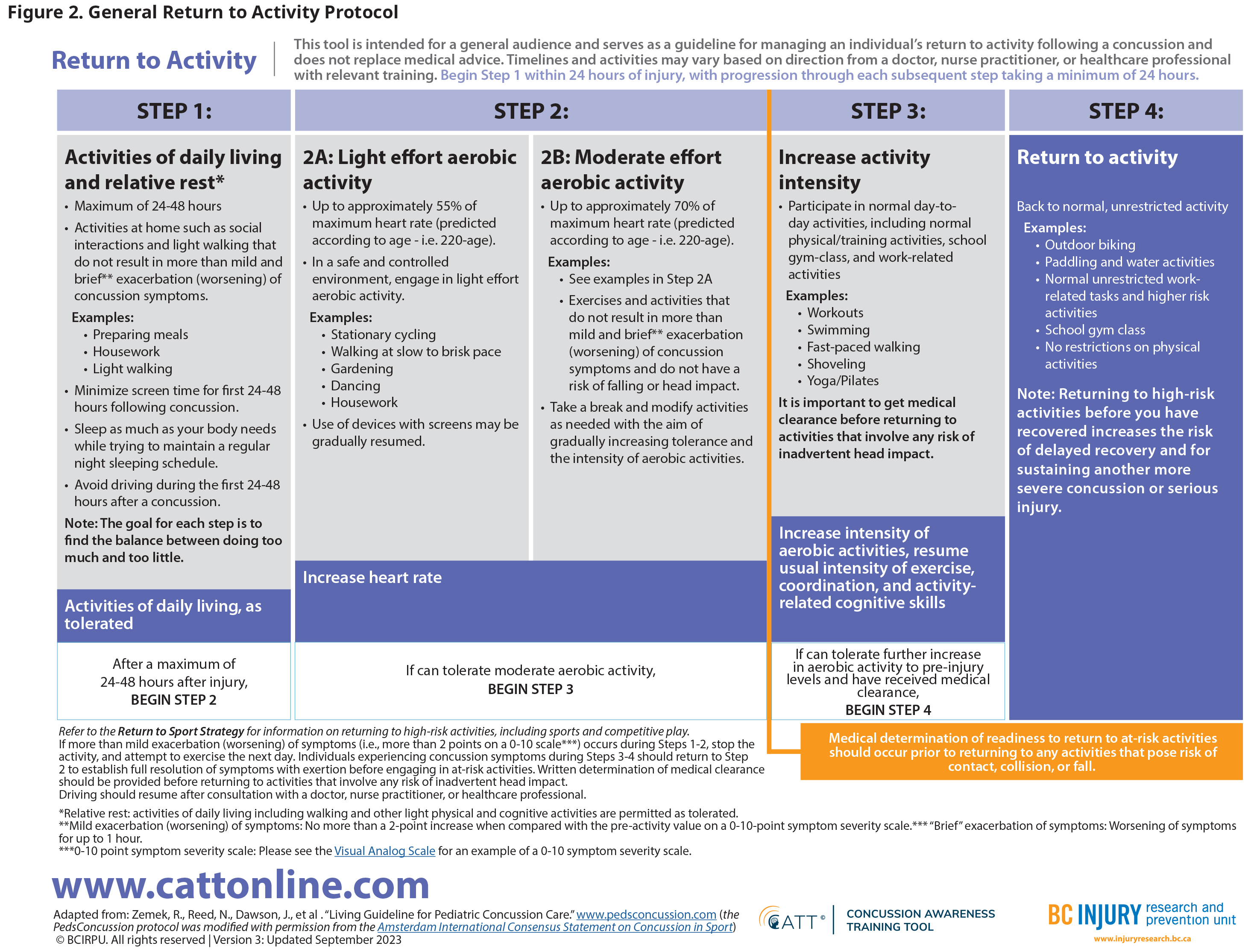

After 24-48 hours of relative rest, patients can initiate a graded return to normal activities even if they have mild residual symptoms. See Figure 2: General Return to Activity Protocol.

- Progression through this protocol is limited to one step per day based on symptom presentation.

- Mild and brief exacerbation of symptoms (i.e., <2 point increase in symptom severity score for <1 hour) is normal and is not associated with longer recovery.23

- If symptoms worsen significantly, the pace of return to activity should be slowed and the patient should return to the previous level of activity that did not worsen symptoms.

- Prescribe light aerobic activity (55% max heart rate) with progression to moderate aerobic activity (70% max heart rate) before determining medical readiness for greater exercise intensity and activities where there is a risk of reinjury.

- Max heart rate = 220-age

Physical Activity/Sport: Patients should be encouraged to return to physical activity as soon as possible as this has been shown to help speed recovery. Aerobic activity should be prioritized prior to advancing through modified sport/recreation activities based on symptom presentation. See Appendix A – Return to Sport Protocol (PDF, 142KB).

School: Patients should return to learning activities as soon as they can tolerate them, with or without accommodations.24 Absence from these activities >1 week is not recommended.24 Collaborate with teachers, support staff, and family members, as appropriate.25 Use of the CATT Student Return to Learn Plan is recommended for ease of documentation. See Appendix B – Return to School Protocol (PDF, 143KB).

Work: Modifications to the work environment and/or demands are often necessary to support an effective return to work. Completion of the CATT Medical Assessment Letter can be helpful to provide clear and documented instruction for the patient and their employer. See Appendix C – Return to Work Protocol (PDF, 146KB).

- WorkSafeBC has two relevant programs for workplace injuries: Early Concussion Assessment and Treatment (ECAT) Program and Post-Concussion Management Program (PCMP). Occupational health consult is also available through the RACE line. Refer to the Practitioner Resources section below.

- Consultation with WorkSafeBC experts is available provincially through the RACE line, both for clinical management of work-related injuries as well as general occupational medicine inquiries.

Driving: Determine whether patient should refrain from driving and whether a Driver’s Medical Examination Report might be required.

Symptom Management

Physical activity and aerobic exercise are important interventions to decrease concussion-related symptoms and reduce the risk of persistent symptoms.20 This activity can begin even in the presence of mild residual symptoms. However, activity should be slowed if there is more than mild and brief exacerbation of symptoms (i.e., >2 point increase in symptom severity score for >1 hour).23 Refer to Figure 2: General Return to Activity Protocol for specific instruction on introducing and increasing aerobic activity intensity.

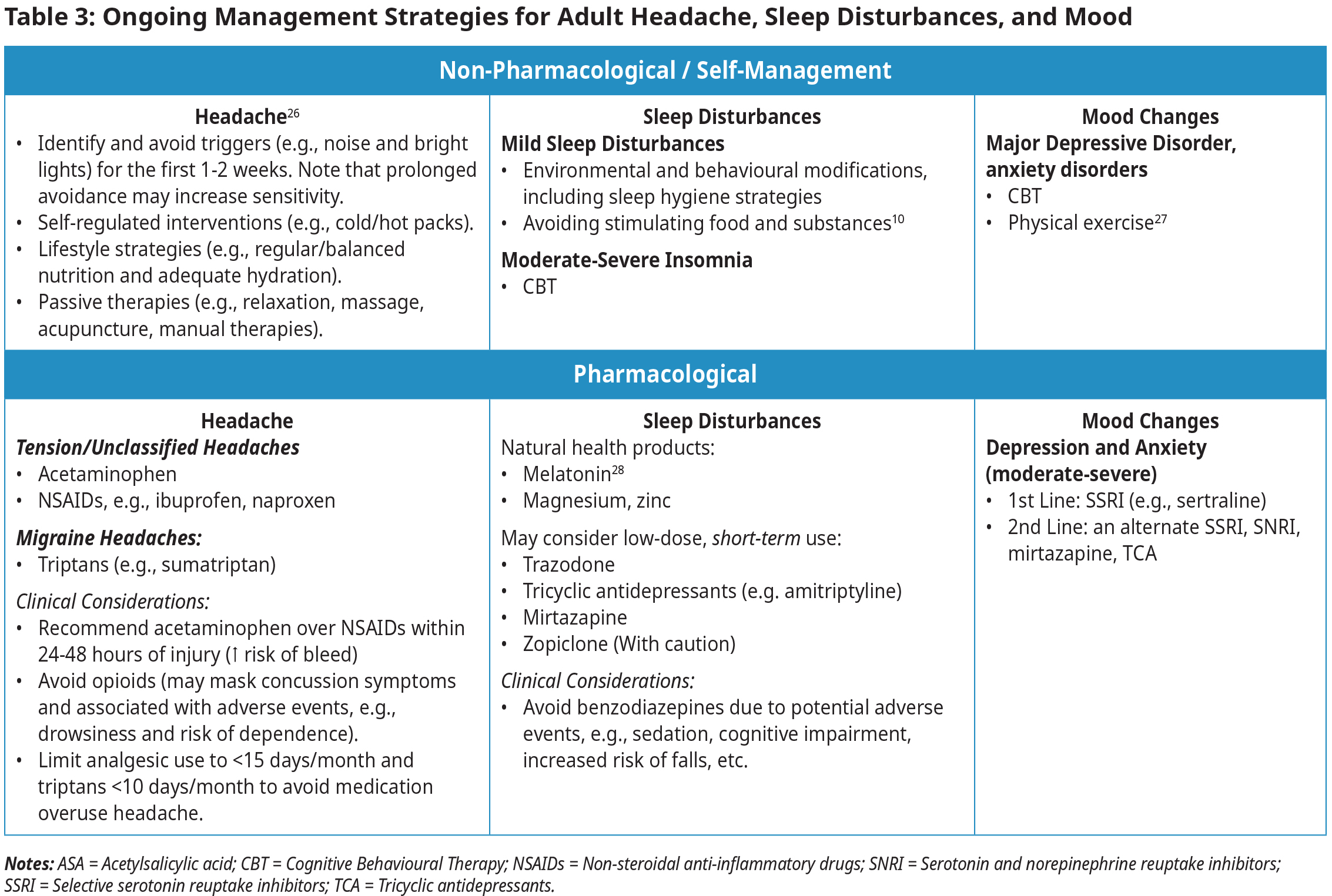

Headache, sleep disturbances, and mood changes are the most important symptoms to manage as these respond best to intervention and may impact other concussion-related symptoms.13 See Table 3: Ongoing Management Strategies for Adult Headache, Sleep Disturbances, and Mood.

- Consider non-pharmacological and self-management approaches first.

- Avoid opiates10 and substances like alcohol, cannabis, and sedatives. These can mask concussion-related symptoms.

Follow-Up

Ideally, all patients should have a primary care follow-up within 2 weeks. Additional follow-up may be required depending on recovery trajectory. The purpose of follow-up is to:

- Assess progress and tolerance of return to activities.

- Determine medical readiness for return to full normal activities and document, if required.

- Screen for persisting symptoms and evaluate for other conditions.

- Consider indications for referral.

1. Assess Progress and Tolerance of Return to Activities

Reassess signs and symptoms while inquiring about progress and tolerance of return to normal activities. Provide additional education with respect to tailoring or proceeding with graded protocols. Provide guidance on appropriate accommodation for work/school/sport activities.

2. Determine Medical Readiness for Return to Full Normal Activities

The graded return to activities protocol requires medical readiness prior to return to at-risk activities (e.g., full contact sport practice or activities with risk of head injury) (See Figure 2: General Return to Activity Protocol).29 Many organizations require documentation of this medical clearance for athletic, learning, or occupational activities. Be aware that social and other pressures may suggest an inappropriate/premature return to activity. If needed, consider completion of the CATT Medical Clearance Letter with explicit written guidance regarding restricted activities. Note appropriately in the patient record.

3. Screen for Persisting Symptoms and Evaluate for Other Conditions

Consider screening for risk of persisting symptoms using either the 5P pediatric risk score30 (5-18 years old) or the Post-Concussion Symptoms Rule (PoCS Rule)31 (≥14 years) (See Appendix E – Screening Tools for Persisting Concussion Symptoms (PDF, 110KB)). These validated tools can help support initial assessment of relevant medical history (e.g., migraines, mental health or mood disorders, etc.).

Consider the following validated tools for other conditions based on patient history, symptoms, and clinical assessment. Treat other conditions while concurrently treating for concussion. Initiate specialist referrals, as appropriate.

- Headache: International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-III)

- Neck Pain: Neck Pain Disability Index

- Anxiety: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale (GAD-7)

- Depression: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)32 or PROMIS Emotional Distress – Anxiety – Short Form for adults, Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (11-item) for adolescents

- Attention Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD): SNAP-IV 26 parent teacher questionnaire, Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1)

- Vestibular Impairment: Vestibular/Ocular Motor Screen (VOMS)

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): Orthostatic vitals monitoring at regular intervals for 10 minutes when supine and then standing, ECG).33 Refer here for more information.

- Substance Use Disorders: CAGE (alcohol) and CAGE-AID (alcohol and other substances)

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): PC-PTSD-5 or PCL-5

4. Consider Indications for Referral

Specialized interdisciplinary care is best initiated early for those who are at risk for persistent symptoms, are highly active, are involved in high-risk activities, have comorbidities, or do not tolerate graded return to activity.

- While management at interdisciplinary concussion clinics is ideal, access is not readily available outside major urban areas. Consider virtual consultations. Refer to the Practitioner Resources section for information on regional health authority services. The RACE line is available provincially for consults in physical and rehabilitation medicine, psychiatry, and WorkSafeBC.

- There is evidence to support cervicovestibular or vestibular rehab for concussion rehabilitation. Consider referral to allied health rehabilitative practitioner(s) with specialty in vestibular rehab (e.g., physiotherapy) for patients with persisting impairments in these domains.1,34 However, these services may not be publicly funded.

Support may be available through WorkSafeBC (e.g., vocational rehabilitation), Veterans Affairs Canada, Victims Services, Insurance Corporation of BC (ICBC), private insurers, First Nations Health Authority, and individual Indigenous bands.

Special Considerations for Children, Older Adults, and Certain Populations

Children

- Young children present with more generalized symptoms of malaise/fatigue/behavior change.35

- While most recover within a normal timeframe without incident,36 children and youth 5-18 years have an increased risk of mental health issues, self-harm, and psychiatric hospitalization following concussion.37 Screen and manage appropriately.

- Where possible, co-manage patients <5 years old with persisting symptoms with a pediatrician. Consultation is available through the RACE and Real Time Virtual Support (RTVS) Child Health Advice in Real-Time Electronically (CHARLiE) programs.

- Children <2 years old should be screened for abuse related head trauma.

Older Adults

- Falls are the most common mechanism of injury for concussion in the older adult.6 Refer to BC Guidelines: Fall Prevention: Risk Assessment and Management for Community-Dwelling Older Adults.

- Cognitive impairment, polypharmacy, and physical aging increase the risk of concussion in older adults.6 Some medications (e.g., sedatives, psychotropics, and antithrombotic) can increase the risk of injury as well as severity/complications.6

- Concussion may be more difficult to diagnosis in the older adult.

- High scores for post-injury neck pain, irritability, and forgetfulness are predictive of increased risk of incomplete recovery in older adults.15

- Older adults might report more issues with balance, fatigue, and noise sensitivity as persisting symptoms.6

Other Special Populations/Scenarios

- Interpersonal violence, including intimate partner violence, and child abuse/neglect are always a consideration with trauma-related presentations. Report as required. Refer for forensic examination, child maltreatment clinic, and/or Victim Support Services, as appropriate.

- Patients with neurological conditions or injuries (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury) will likely require an altered approach to assessment and management. Consider specialist involvement.

- Mental health sequelae of concussion are often under-reported, under-appreciated and may surface in a gradual or insidious way. Maintain a high index of suspicion, screen and manage appropriately.

- Repetitive head trauma is a risk factor for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). CTE is associated with progressive neurological deterioration and symptoms, including changes in behaviour/mood, memory loss, cognitive impairment, and dementia.38 However, CTE has been described exclusively based on autopsy studies in certain professional athletes (i.e., football players, boxers) and combat personnel.38

- Second impact syndrome can result from subsequent head trauma leading to diffuse cerebral swelling and brain herniation. This is a controversial diagnosis and is exceptionally rare.

Controversies in Care

- The American Congress of Rehabilitative Medicine (ACRM) exclusion criteria2 for mTBI list LOC >30 min and GCS <13 at 30 minutes post injury. However, many clinical experts suggest that almost any LOC and a GCS <15 at 30 minutes would be sufficient to exclude mTBI and raise consideration of more severe brain injury.

- While the full ACRM diagnostic criteria reference laboratory test findings for diagnosis of mTBI, such tests are not currently available in BC nor are they universally used in specialized concussion clinics.

Resources

Abbreviations

| ACRM | American Congress of Rehabilitative Medicine | LOC | Loss of Consciousness |

| ASA | Acetylsalicylic acid | mTBI | Mild Traumatic Brain Injury |

| CATT | Concussion Awareness Training Tool | NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioural Therapy | PCMP | Post-Concussion Management Program (WorkSafeBC) |

| ciTBI | Clinically Important TBI | POTS | Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome |

| CT | Computed Tomography | ROM | Range of Motion |

| CTE | Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy | SCAT | Sport Concussion Assessment Tool |

| ECAT | Early Concussion Assessment and Treatment (WorkSafeBC) | SCOAT | Sport Concussion Office Assessment Tool |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram | SNRI | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram | SSRI | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale | TCA | Tricyclic antidepressants |

| ICBC | Insurance Corporation of BC | VOMS | Vestibular Ocular Motor Screening |

Practitioner Resources

- Health Authority Concussion Clinics

- Vancouver Coastal:

- G.F. Strong Adult Concussion Service: Two services (1) Early Response Concussion Service, and (2) Self-Management Program.

- G.F. Strong Adolescent Complex Concussion Clinic (12-18 years old) for interdisciplinary rehabilitation.

- Fraser:

- Fraser Health Concussion Clinic: Early education and link to specialists, as needed.

- Embrace Clinic and Strangulation Clinic for victims of recent violence, including head injuries from violence. Self-referral or referral by professional with patient consent – 604-827-5406 or www.fraserhealth.ca/embraceclinic (available to any person living in BC, located in Surrey, BC.)

- Island, Northern, and Interior Health: No dedicated concussion program.

- Vancouver Coastal:

- Standardized Concussion Assessment Tool Examples

- Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE)

- <72 hours – Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT). See Adult SCAT6 and Child SCAT6.

- >72 hours – Sport Concussion Office Assessment Tool (SCOAT). See Adult SCOAT6 and Child SCOAT6.

- Continuing Medical Education: UBC-CPD / BC Children’s Hospital / Pediatrics and Parachute developed an online Concussion Awareness Training Tool (CATT) for medical professionals.

- Pathways BC: An on-line referral resource for clinicians available through all Divisions of Family Practice in BC. Membership in a regional Division of Family Practice is required to access.

- Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise (RACE): A phone consultation line for physicians, nurse practitioners and medical residents. If the relevant specialty area is available through your local RACE line, please contact them first. | Monday to Friday 0800 – 1700 | Toll Free: 1–877–696–2131

- Real Time Virtual Support (RTVS): Available to support practitioners in rural, remote, and First Nations communities in BC.

- Rural Urgent Doctor in aid (RUDi) for instant emergency medicine support.

- Child Health Advice in Real-Time Electronically (CHARLiE) for instant pediatric support.

- Health Data Coalition: An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing.

- Family Practice Services Committee

- Practice Support Program: Offers focused, accredited training sessions for BC physicians to help them improve practice efficiency and support enhanced patient care.

- Chronic Disease Management and Complex Care Incentives: Compensates family physicians for the time and skill needed to work with patients with complex conditions or specific chronic diseases.

- Public Health Agency of Canada: Provides resources to help patients make wise choices about healthy living, including increasing physical activity and eating well.

- Relevant BC Guidelines

- Other Concussion Symptom Severity Scoresheets

- CATT Medical Clearance Letter

- Other Canadian Clinical Resources for Concussion

Patient, Family and Caregiver Resources

- Concussion Awareness Training Tool (CATT): For youth, athletes, caregivers, coaches, school professionals, workers and workplaces, women’s support worker, and medical professionals.

- HealthLinkBC: Patients can call HealthLinkBC at 8-1-1 toll-free in B.C., or for the deaf and the hard of hearing, call 7-1-1. Patients will be connected with an English-speaking health-service navigator who can provide health and health-service information, and connect them with a registered dietitian, exercise physiologist, nurse, or pharmacist.

- Vancouver Coastal Health My Guide - Adult Concussion: Customizable self-management tool for adults.

- Vancouver Coastal Health My Guide-Teen Concussion: Customizable self-management tool for adolescents.

- Crime Victims Assistance Program: Assists victims, immediate family and some witnesses in coping with the effects of violent crime. This can include medical and dental services, prescription drug expenses, counselling, childcare, etc.

- Return to Learn information: Public Health Agency of Canada or GF Strong School Program

- Support for interpersonal violence: Ending Violence Association of Canada

- Mental Health support: BounceBack BC: Online or phone coaching for youth (13-18) and adults (18+)

- Self-Management BC for free general health support.

Diagnostic Codes

- 850.0-850.9: Concussion, excludes concussion with 1) cerebral laceration or contusion, and 2) cerebral hemorrhage.

- 959.01: Head injury, unspecified

Billing Codes

- ED: Level II (01812, 01822, 01832, 01842) or Level III (01813, 01823, 01833, 01843)

- Family: Exam / Visit / Counselling

Appendices

- Appendix A – Return to Sport Protocol (PDF, 142KB)

- Appendix B – Return to School Protocol (PDF, 143KB)

- Appendix C – Return to Work Protocol (PDF, 146KB)

- Appendix D – Patient Education Handout (PDF, 258KB)

- Appendix E – Screening Tools for Persisting Concussion Symptoms (PDF, 110KB)

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

References

- Patricios JS, Schneider KJ, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport–Amsterdam, October 2022. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(11):695-711. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2023-106898

- Silverberg ND, Iverson GL, Cogan A, et al. The American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine Diagnostic Criteria for Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2023.03.036

- McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—the 5 th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. Published online April 26, 2017:bjsports-2017-097699. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097699

- Concussion Awareness Training Tool. BC Injury Prevention and Research Institute https://cattonline.com/

- The Burden of Concussion in British Columbia. Accessed July 12, 2022. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubccommunityandpartnerspublicati/52387/items/1.0396146

- Huang B, Babul S. Concussions and Older Adults. A Report by the BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit. BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit; 2022.

- Cancelliere C, Verville L, Stubbs JL, et al. Post-Concussion Symptoms and Disability in Adults with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Neurotrauma. Published online January 18, 2023:neu.2022.0185. doi:10.1089/neu.2022.0185

- Kamins J, Bigler E, Covassin T, et al. What is the physiological time to recovery after concussion? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(12):935-940. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097464

- Eisenberg MA, Meehan WP, Mannix R. Duration and Course of Post-Concussive Symptoms. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):999-1006. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0158

- Silverberg ND, Iaccarino MA, Panenka WJ, et al. Management of Concussion and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Synthesis of Practice Guidelines. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(2):382-393. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2019.10.179

- Leddy JJ, Sandhu H, Sodhi V, Baker JG, Willer B. Rehabilitation of Concussion and Post-concussion Syndrome. Sports Health Multidiscip Approach. 2012;4(2):147-154. doi:10.1177/1941738111433673

- King NS, Crawford S, Wenden FJ, Moss NEG, Wade DT. The Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire: a measure of symptoms commonly experienced after head injury and its reliability. J Neurol. 1995;242(9):587-592. doi:10.1007/BF00868811

- Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation. Standards for Post-Concussion Care. Published online June 8, 2017. http://concussionsontario.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ONF-Standards-for-Post-Concussion-Care-June-8-2017.pdf

- Iverson GL, Gardner AJ, Terry DP, et al. Predictors of clinical recovery from concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(12):941-948. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097729

- Bittencourt M, Balart-Sánchez SA, Maurits NM, van der Naalt J. Self-Reported Complaints as Prognostic Markers for Outcome After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Elderly: A Machine Learning Approach. Front Neurol. 2021;12:751539. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.751539

- Lubbers VF, Van Den Hoven DJ, Van Der Naalt J, Jellema K, Van Den Brand C, Backus B. Emergency Department Risk Factors for Post-Concussion Syndrome After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. J Neurotrauma. Published online March 13, 2024:neu.2023.0302. doi:10.1089/neu.2023.0302

- Sutton M, Chan V, Escobar M, Mollayeva T, Hu Z, Colantonio A. Neck Injury Comorbidity in Concussion-Related Emergency Department Visits: A Population-Based Study of Sex Differences Across the Life Span. J Womens Health. 2019;28(4):473-482. doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.7282

- Leddy J, Baker JG, Haider MN, Hinds A, Willer B. A Physiological Approach to Prolonged Recovery From Sport-Related Concussion. J Athl Train. 2017;52(3):299-308. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.08

- Eliason PH, Galarneau JM, Kolstad AT, et al. Prevention strategies and modifiable risk factors for sport-related concussions and head impacts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(12):749-761. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-106656

- Carter KM, Pauhl AN, Christie AD. The Role of Active Rehabilitation in Concussion Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(9):1835-1845. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002663

- Macnow T, Curran T, Tolliday C, et al. Effect of Screen Time on Recovery From Concussion: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1124. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2782

- Cairncross M, Yeates KO, Tang K, et al. Early Postinjury Screen Time and Concussion Recovery. Pediatrics. 2022;150(5):e2022056835. doi:10.1542/peds.2022-056835

- Leddy JJ, Burma JS, Toomey CM, et al. Rest and exercise early after sport-related concussion: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Reed N, Zemek R, Dawson J, et al. Living guideline for pediatric concussion care (PedsConcussion). PedsConcussion. Published online 2022. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/3VWN9

- Dawson J, Johnston S, McFarland S, Reed N, Zemek R. Returning to school following concussion: Pointers for family physicians from the Living Guideline for Pediatric Concussion Care. Can Fam Physician. 2023;69(6):382-386. doi:10.46747/cfp.6906382

- Marshall S, Bayley M, McCullagh S, et al. Living Concussion Guidelines: Guideline for Concussion & Prolonged Symptoms for Adults 18 Years of Age or Older. Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; 2018.

- Croatto G, Vancampfort D, Miola A, et al. The impact of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions on physical health outcomes in people with mood disorders across the lifespan: An umbrella review of the evidence from randomised controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(1):369-390. doi:10.1038/s41380-022-01770-w

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-Analysis: Melatonin for the Treatment of Primary Sleep Disorders. Romanovsky AA, ed. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63773. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063773

- Putukian M, Purcell L, Schneider KJ, et al. Clinical recovery from concussion–return to school and sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(12):798-809. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-106682

- Zemek R, Barrowman N, Freedman SB, et al. Clinical Risk Score for Persistent Postconcussion Symptoms Among Children With Acute Concussion in the ED. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1014. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.1203

- Le Sage N, Chauny JM, Berthelot S, et al. PoCS Rule : Derivation and Validation of a Clinical Decision Rule for Early Prediction of Persistent Symptoms after a mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. Published online June 29, 2022:neu.2022.0026. doi:10.1089/neu.2022.0026

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Raj SR, Fedorowski A, Sheldon RS. Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Can Med Assoc J. 2022;194(10):E378-E385. doi:10.1503/cmaj.211373

- Schneider KJ, Critchley ML, Anderson V, et al. Targeted interventions and their effect on recovery in children, adolescents and adults who have sustained a sport-related concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(12):771-779. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2022-106685

- Dupont D, Beaudoin C, Désiré N, Tran M, Gagnon I, Beauchamp MH. Report of Early Childhood Traumatic Injury Observations & Symptoms: Preliminary Validation of an Observational Measure of Postconcussive Symptoms. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2022;37(2):E102-E112. doi:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000691

- Keightley ML, Côté P, Rumney P, et al. Psychosocial Consequences of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Children: Results of a Systematic Review by the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(3):S192-S200. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.12.018

- Ledoux AA, Webster RJ, Clarke AE, et al. Risk of Mental Health Problems in Children and Youths Following Concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e221235. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1235

- McKee AC, Stein TD, Kiernan PT, Alvarez VE. The Neuropathology of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: CTE Neuropathology. Brain Pathol. 2015;25(3):350-364. doi:10.1111/bpa.12248

- Chen J, Johnston KM, Collie A, McCrory P, Ptito A. A validation of the post concussion symptom scale in the assessment of complex concussion using cognitive testing and functional MRI. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(11):1231-1238. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.110395

|

BC Guidelines are developed for the Medical Services Commission by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, a joint committee of Government and the Doctors of BC. BC Guidelines are adopted under the Medicare Protection Act and, where relevant, the Laboratory Services Act. Disclaimer: This extended learning document is based on best available scientific evidence and clinical expertise as of September 19, 2024. It is not intended as a substitute for the clinical or professional judgment of a health care practitioner. |

TOP

TOP