Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack - Acute and Long-Term Management

Effective Date: April 1, 2015

This guideline was developed over 5 years ago

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Epidemiology

- Risk Factors & Primary Prevention

- Diagnosis

- Acute Management

- Long-Term Management

- Resources

- Appendices

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for the acute and long-term management of stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) in adults aged ≥ 19 years, in the primary care setting. This includes secondary stroke/TIA prevention and medications.

This guideline is part of the BCGuidelines.ca - Stroke and Atrial Fibrillation series. The series includes three other guidelines: Atrial Fibrillation – Diagnosis and Management; Use of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants (NOAC) in Atrial Fibrillation; and Warfarin Therapy Management.

Key Recommendations

- Strokes and emergent transient ischemic attacks are medical emergencies and patients should be immediately sent to an emergency department.

- Timely investigation and management of transient ischemic attacks significantly reduces the chance of stroke.

- Thrombolytic eligible patients should receive tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) as quickly as possible (within 4.5 hours of clearly defined symptom onset).

- Early mobilization and appropriate positioning within 24 hours are associated with improved outcomes.

- Management on a stroke rehabilitation unit improves functional outcomes.

Definition

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a brief episode of neurologic dysfunction caused by focal brain or retinal ischemia without evidence of acute infarction.1 Clinical symptoms typically last minutes to one hour (although they can last up to 24 hours). These symptoms can include motor, sensory, speech/language, vision or cerebellar disturbances. A TIA can be seen along the same pathophysiological process as a stroke. Even with the resolution of symptoms, an infarct may have occurred and should be treated as a continuum of the same disease process as a stroke.

A stroke is defined as the sudden onset of focal neurological deficit resulting from either infarction or hemorrhage within the brain. Symptoms of a stroke are similar to that of TIA, however, they are not temporary.

Strokes are a major cause of death and disability in BC. Approximately 4900 incident cases of stroke are hospitalized in BC each year with a 13% mortality rate for all prevalent cases.2 About 80% of strokes are ischemic/thrombotic and 20% are hemorrhagic.3 A significant proportion of patients with a stroke survive; rapid assessment and treatment are considered critical to reducing disability and mortality related to stroke.

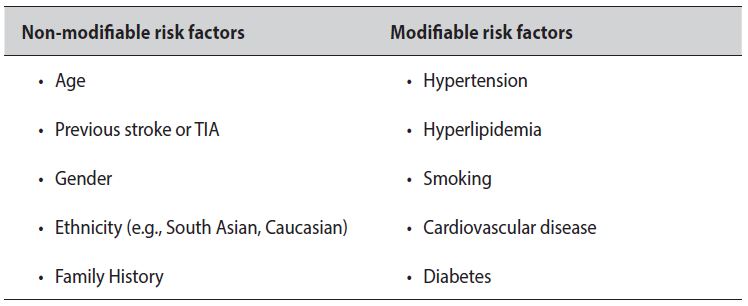

The major treatable risk factors for cerebrovascular atherosclerotic disease are similar to those for coronary atherosclerosis.4

Table 1: Risk factors for stroke or TIA

Individuals with atrial fibrillation have a 3 to 5 times greater risk for ischemic stroke.5 It is estimated that more than 20% of all strokes are caused by atrial fibrillation.3 Further information about atrial fibrillation and stroke risk can be found in BCGuidelines.ca - Atrial Fibrillation – Diagnosis and Management.

Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease also reduces incidence of cerebrovascular disease (see BCGuidelines.ca - Cardiovascular Disease - Primary Prevention and Hypertension - Diagnosis and Management guidelines).

Diagnosis: Stroke or TIA

Key features of a stroke/TIA are: 1) sudden onset; and 2) focal neurological deficits associated with a specific cerebral vascular territory. For example:6

- Weakness − sudden loss of strength or numbness in the face, arm or leg

- Difficulty with speech − sudden confusion or trouble speaking

- Vision problems − sudden trouble with vision

- Headache − sudden severe and unusual headache

- Dizziness − loss of balance, especially with any of the above signs

Differential Diagnosis

History is critical in differentiating diagnoses when first presenting. Patients with TIA will have complete resolution of symptoms and signs while stroke patients may have persistent symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis for Suspected TIA: In addition to TIAs, the most important and frequent causes of discrete self-limited attacks include seizures, migraine with aura, syncope and vertigo due to peripheral vestibulopathies. When assessing the patient, look for signs and symptoms of vasculitis, sinusitis, mastoiditis and meningitis for a possible differential diagnosis or possible alternate etiology.

Differential Diagnosis for Suspected Stroke: This includes seizures, tumours, abscesses, arteriovenous malformations, subdural hematomas, demyelination, focal encephalitis, vasculitis, Bell's palsy, plexopathies, mononeuropathies and upper cord lesions.

Basic examination of all patients includes a neurological and cardiovascular exam, with vital signs and carotid auscultation. Glucometer check should be done. A brief assessment tool for triage purposes can be found in Appendix A: Cincinnati Stroke Scale.7

Assessment

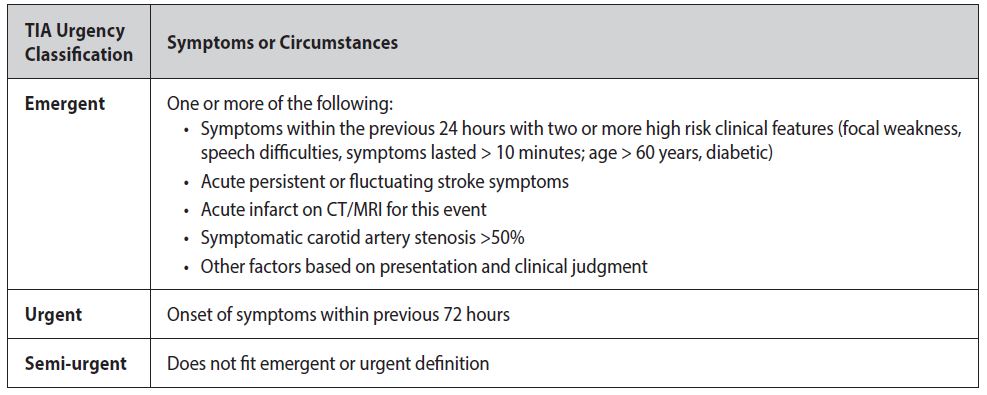

Timing: Strokes and emergent TIAs are medical emergencies and patients should be immediately sent to an emergency department. See definition of emergent TIAs in Table 2. Investigation and treatment of strokes or TIAs should begin as soon as possible, preferably within 24 hours. Contact information for stroke/TIA assessment clinics throughout BC are listed in the Resources below.

Investigations for urgent cases are recommended within 7 days, and within one month for semi-urgent cases.

Table 2. TIA urgency classification

Rationale for Urgency of Assessment: TIA patients are at high risk for stroke. Timely investigation and management of TIAs significantly reduces the chance of stroke. The average risk of stroke after a TIA is up to 3% in the first 2 days, 5% in the first week and up to 12% at 90 days.8 A patient’s 90 day risk can be lowered from 12% to about 2% with timely (< 24 hour) investigation and aggressive management.9

The ABCD2 score with vascular imaging is available to assess the short term stroke risk after presenting with TIA.10 The score predicts the risk of stroke within 2 days after a TIA, but also predicts stroke risk within 90 days.11 See Appendix B - ABCD2: To Assess 2-Day Stroke Risk After a TIA.

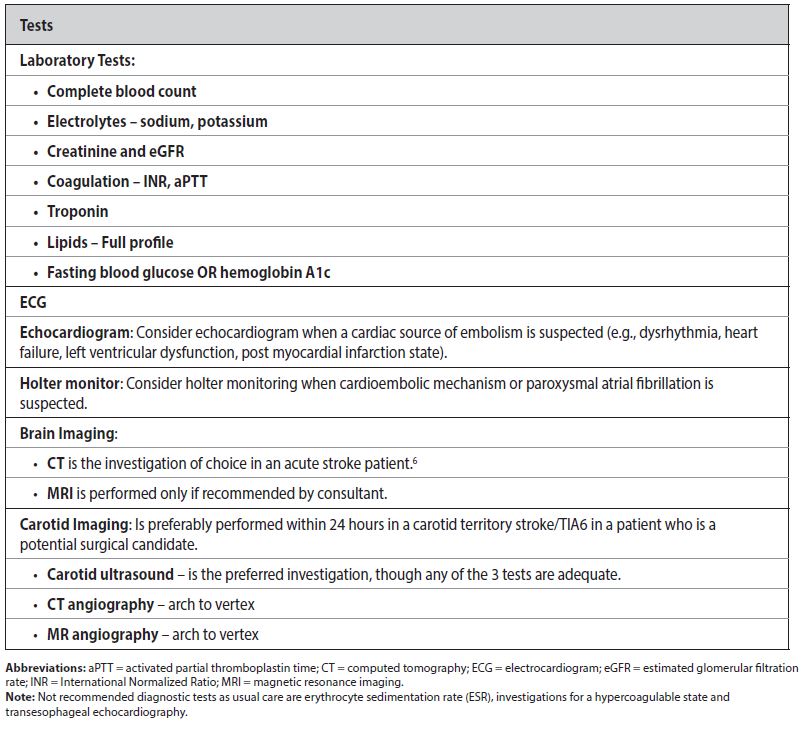

Initial Investigations

The initial investigations for emergent TIA and a suspected acute stroke are the same (see Table 3). Patients diagnosed with a non-emergent TIA may be referred to an internist/neurologist or a rapid stroke assessment unit. Alternately, a physician may decide to investigate/manage patients diagnosed with a non-emergent TIA as outpatients.

Table 3. Diagnostic tests for stroke/TIA6

For an emergent TIA, computed tomography angiography (CTA) from arch to vertex (where available) is preferred over carotid ultrasound in those with no contraindication of CTA. The utility of CTA in emergent TIA or minor stroke is twofold: 1) to image the carotid artery to rule out carotid stenosis as an underlying cause of ischemic stroke; and 2) to help predict risk of recurrence.12 Patients with CT/CTA abnormalities including acute ischemia, intracranial/extracranial occlusion, or stenosis ≥50% are at increased risk of early recurrent stroke.

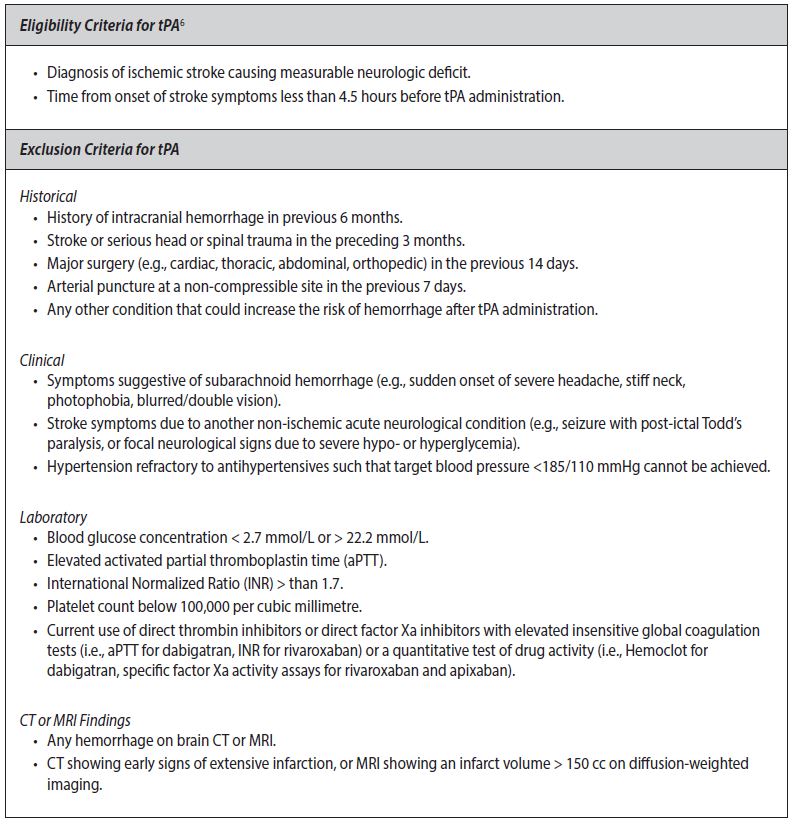

Immediate Management of Stroke/TIA in the Emergency Department/Rural Setting

Once diagnosed (see Table 3 above for investigations), determine eligibility for tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy immediately (see Table 4 for criteria). Thrombolytic eligible patients should receive tPA as quickly as possible (within 4.5 hours of clearly defined symptom onset). Benefits of tPA are time critical; the earlier the treatment, the better the outcomes. At the present time there is a lack of evidence in using other thrombolytic agents for stroke. If tPA is not available, consult a stroke neurologist.

Table 4: Criteria for tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) therapy

Once the patient’s eligibility for tPA therapy has been determined, proceed with management recommendations listed in Table 5.

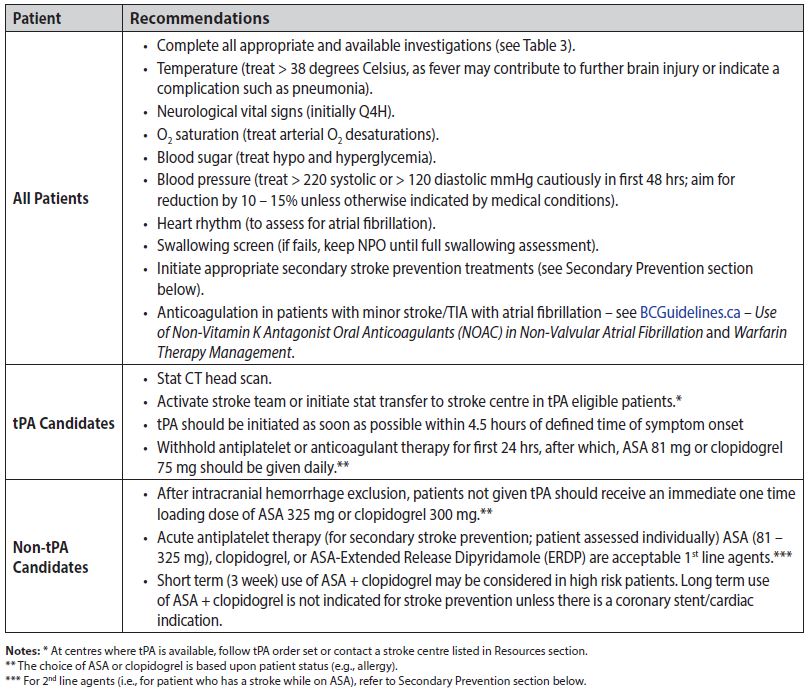

Table 5: Management recommendations for all stroke/TIA, including tPA and non-tPA candidates

Continuing Management of Stroke/TIA in the Emergency Department/Rural Setting

Manage stroke patients on an acute stroke or general neurological unit where possible. Patients who have received tPA should be monitored in an intensive care unit. It is recommended that the core interdisciplinary team (e.g., medical, nursing, nutrition, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, social work and speech-language staff) assess patient within 48 hours of admission. This improves quality of life and can help prevent some of the medical complications of stroke.13

Prevention of Medical Complications

There are multiple possible complications post-stroke.14 Early mobilization and appropriate positioning during the first 24 hours are associated with improved outcomes. Some of the most serious or common complications are:

Serious cardiac complications: Common in the first three months post-stroke.15

Depression: Estimated to affect up to 1/3 of patients; assess and treat individually. Refer to BCGuidelines.ca - Major Depressive Disorder in Adults - Diagnosis and Management for more information.

Dysphagia/malnutrition/dehydration: Optimize positioning for meals (e.g., sitting upright in chair unless contraindicated); consider enteral feeding if no oral intake for > 48 hours. There is a reduction in risk of aspiration pneumonia when swallowing is managed early by a speech therapist.

Decubitus ulcer formation: Long lasting ulcers can develop rapidly in poorly mobilized patients; focus on positioning and nutritional support as well as mattress optimization.

Shoulder pain with hemiplegia: Consider referral to physiotherapist and physiatrist.

Venous thromboembolism: Pulmonary embolism accounts for 13-25% of early deaths post-stroke.16 Assess patients for prophylaxis with anticoagulant and/or leg compression with pneumatic compression devices. Graduated compression stockings are contraindicated.

Malignant middle cerebral artery (MCA) syndrome: Consider neurosurgical referral for possible hemicraniectomy in patients < 60 years of age with massive MCA infarcts where severe cerebral edema may otherwise lead to fatal brain infarction. Surgery is generally done within the first 48 hours after stroke onset. Candidates should be identified within the first 24 - 36 hours.

Communication Upon Discharge

Provide stroke education and follow up information to the patient (refer to Patient Information section). Communication with the patient’s family physician is of utmost importance at the time of hospital discharge after treatment for a stroke/TIA. It is desirable that a discharge summary be sent expeditiously to the family physician and that a copy is given to the patient.

Secondary Prevention

Preventing a second stroke is vital in patient care. Ischemic stroke is not a single disease. It can be due to number of different stroke mechanisms and each has its natural history and treatment strategy. Investigations identify the underlying cause of the ischemic stroke in an individual patient and help provide appropriate secondary prevention.

Carotid Endarterectomy: Recommended in patients with internal carotid artery stenosis > 70%, with symptoms in carotid territory, a surgical risk < 6%, and life expectancy exceeding 5 years. In these patients, it is recommended that surgery be offered within 2 weeks of the TIA. Patients with carotid stenosis of 50 - 70% can be evaluated for surgery on an individual basis. Carotid stenting is an option in high risk surgical patients.

Anticoagulation: For appropriate patients with atrial fibrillation or another high risk cardiac source, anticoagulants are recommended. Details on anticoagulant management can be found within BCGuidelines.ca - Atrial Fibrillation – Diagnosis and Management; Use of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants (NOAC) in Atrial Fibrillation; and Warfarin Therapy Management. The timing of initiation of anticoagulation in patients who had an atrial fibrillation related stroke is determined by clinical judgment on a case by case basis, with consideration of risk of hemorrhagic transformation and risk of recurrent stroke.

Antiplatelet Therapy: Indicated for all ischemic stroke patients unless there is an indication for warfarin therapy. ASA, clopidogrel and the combination of extended release dipyridamole plus ASA are all acceptable antiplatelet agents for secondary stroke prevention.

Recent evidence demonstrates that clopidogrel and extended release dipyridamole plus ASA have similar efficacy in secondary stroke prevention.17 There is some evidence showing superiority of clopidogrel or dipyridamole plus ASA over ASA.18-20 Base the choice of therapy on patient risk, compliance, side effect profile and cost (see Appendix C: Prescription Medication Table for Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack).

The long-term use of clopidogrel plus ASA is not recommended for secondary stroke prevention unless there is a cardiac indication.21,22

For patients who have a stroke while on antiplatelet therapy, investigate the cause to exclude high risk cardiac source or need for carotid endarterectomy. Consider a change of antiplatelet therapy.

Hypertension: Treatment of hypertension with antihypertensive drugs is associated with reduction in recurrent strokes.23,24 There is no clear target blood pressure, but benefit can be achieved with a reduction of 10/5 mmHg.23 BCGuidelines.ca – Hypertension - Diagnosis and Management guidelines suggest blood pressure readings of < 140/90 as recommended for all patients at high risk for ischemic cardiovascular disease (for acute control see Table 4). Lifestyle modifications associated with blood pressure reduction should be included as part of an antihypertensive regimen.

Dyslipidemia: There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against statin therapy in the acute phase (first 48 hours) of TIA or stroke management. The benefit of statins for secondary prevention of strokes has been demonstrated in systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials.25,26 Consider prescribing a statin for patients who have had a stroke or TIA in order to achieve a reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). No clear target level of total or LDL-C is currently available for stroke/TIA patients,27 but LDL-C of ≤ 2.0 mmol/L, or ≥ 50% reduction has been suggested for high risk cardiovascular disease patients.28

Diabetes: Diabetes is a clear risk factor for first stroke but data are less conclusive about recurrent stroke.29 Refer to BCGuidelines.ca - Diabetes Care for information on management of diabetes.

Lifestyle: Smoking cessation, limited alcohol consumption, weight control, regular aerobic physical activity, and a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products are recommended.11 Refer to BCGuidelines.ca – Lifestyle & Self-Management Supplement for more information (In Progress).

Stroke Education: Provide stroke education and follow up information to every patient. (Refer to Patient Information section.)

Rehabilitation

Assess the patient for their rehabilitation needs:

- If hospitalized, have the patient with an acute stroke assessed by a rehabilitation professional as soon as possible after admission.

- If not hospitalized, have the patient with acute stroke and any residual stroke-related impairments undergo a comprehensive outpatient assessment for functional impairment. This includes a cognitive evaluation, screening for depression, screening of fitness to drive (website: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/family-social-supports/seniors/transportation/driving-your-own-vehicle/driver-fitness-and-assessment), and functional assessments for potential rehabilitation treatment (within 2 weeks preferred).6

Management on a stroke rehabilitation unit improves functional outcomes (durable for up to 1 year).14 Referral to an stroke rehabilitation unit is appropriate when these admission criteria are met: medically stable; requires 24/7 nursing care; requires at least two rehab services (e.g., physiotherapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), speech-language pathology (SLP) or neuropsychology); can tolerate > 3 hours of activity.

Components of stroke rehabilitation are summarized below to aid the family physician in arranging these services. For a detailed discussion see the Evidence-Based Review of Stroke Rehabilitation (EBRSR), website: www.ebrsr.com.

Ataxia, Gait Disturbance, and/or Falls: Mobilize patients within 24 hours, provided that they are alert and hemodynamically stable. Rehabilitation includes lower limb strength training to increase walking distance after stroke. Gait and/or standing post-stroke are improved with gait retraining (including task-specific), balance training, electromyography (EMG)-biofeedback training, and functional electrical stimulation.

Dexterity: Consider referral of patients with upper limb weakness or decreased coordination for physical and occupational therapy. Mental practice is associated with improved motor performance and activities of daily living performance.

Cognitive Dysfunction: Compensatory strategies (e.g., reminders, day planners) improve memory outcomes. Consider referral of patients with cognitive deficits either for neuropsychological assessment or to an OT trained in cognitive evaluation. Also consider referral to driving simulation training or assessment programs.

Neglect: Visual scanning techniques and limb activation therapies improve neglect. Consider referral of patients with hemisensory neglect for perceptual retraining by an OT and/or neuropsychologist.

Dysarthria and Dysphasia: Consider referral of patients with impaired speech for assessment and training. Intensive speech and language therapy in the acute phase, especially with severely aphasic patients, showed significant improvement in language outcomes.

Hemianopsia: Consider ophthalmologist referral regarding optical prisms for patients with homonymous hemianopsia as this improves visual perception scores.

Community Re-Integration: Referral to community-based support services is associated with increased social activity. Education and information also have a positive benefit.

Resources

References

- Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack-proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1713-6.

- Primary Health Care ACVS Hospital Stroke Registry, 2012/13 and created as November, 2013. BC Ministry of Health.

- Lu L. Evaluation and management of ischemic stroke. MUMJ. 2011;8:39-44.

- Furie KL, Roast NS. Secondary prevention of stroke: risk factor reduction. UpToDate® [Internet]. 2014 Jun 17 [cited 2014 Jul 08].

- European Heart Rhythm Association, European Association of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Camm AJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. The Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ECS) [erratum in 2011;32:1172]. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369-429.

- Lindsay MP, Gubitz G, Bayley M, et al. Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2014 Aug 27].

- Kothari RU, Pangioli A, Liu T et al. Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: Reproducibility and validity. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;33:373-80.

- Giles MF and Rothwell PM. Risk of stroke early after transient ischaemic attack: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:1063-72.

- Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Marquardt L, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): A prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;6:953-60.

- Purroy F, Jimenez Caballero PE, Gorospe A, et al. Prediction of early stroke recurrence in transient ischemic attack patients from PROMAPA study: a comparison of prognostic risk scores. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33:182-189.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Huynh-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369:283-292.

- Cuspidi C, Muiesan ML, Valagussa L, et al. Comparative effects of candesartan and enalapril on left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with essential hypertension: The candesartan assessment in the treatment of cardiac hypertrophy (CATCH) study. Journal of Hypertension 2002;20:2293-2300.

- The IST-3 collaborative group. Effect of thrombolysis with alteplase within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke on long-term outcomes (3rd International Stroke Trial [IST-3]): 18-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:768–76.

- Teasell R, Foley NC, Bhogal SK, et al. An evidence-based review of stroke rehabilitation. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2003;10(1):28-58.

- Prosser J, MacGregor L, Lees KR, et al. Predictors of early cardiac morbidity and mortality after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:2295-302. Epub Jun 14.

- Kelly J, Rudd A, Lewis R, et al. Venous thromboembolism after stroke. Stroke. 2001;32:262-7.

- Diener HC, Sacco R, Yusuf S, et al. Rationale, design and baseline data of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial comparing two antithrombotic regimens (a fixed-dose combination of extended-release dipyridamole plus ASA with clopidogrel) and telmisartan versus placebo in patients with strokes: the Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes Trial (PRoFESS). Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23(5-6):368-80. Epub 2007 Feb 26.

- Diener HC, Darius H, Bertrand-Hardy JM, et al. Cardiac safety in the European Stroke Prevention Study 2 (ESPS2). Int J Clin Pract. 2001;55:162-3

- The ESPRIT Study Group. Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT). Lancet. 2006;367:1665-1673.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet. 1996;348:1329-39.

- Hart RG, Bhatt DL, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of stroke in patients with a history of atrial fibrillation: Subgroup analysis of the CHARISMA randomized trial. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:344-347.

- Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004 Jul 24-30;364:331-7.

- Rashid P, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath P. Blood pressure reduction and secondary prevention of stroke and other vascular events: A systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34:2741-2748.

- Royal College of Physicians (UK). National clinical guidelines for stroke. Prepared by the Intercollegiate Working Party. 4th ed:2012.

- Amarenco P, Goldstein LB, Szarek M, et al. Effects of intense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial. Stroke. 2007;38:3198-3204.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: A randomised placebo controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:549-59.

- Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, et al. Prognostic significance of visit to visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet 2010;375:895-905.

- Anderson TJ, Grégoire J, Hegele RA, et al. 2012 Update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2013;29:151-67.

- Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42:227-276.

Resources

- BC Guidelines, www.BCGuidelines.ca - Cardiovascular Disease – Primary Prevention; Diabetes Care, Hypertension – Diagnosis and Management; Lifestyle and Self-Management Supplement.

- Stroke Services BC, www.phsa.ca/AgenciesAndServices/Services/stroke-services-bc.htm

- Canadian Stroke Best Practices, www.strokebestpractices.ca

- Heart and Stroke Foundation - British Columbia and Yukon, https://www.heartandstroke.ca/

- Canadian Stroke Network, www.canadianstrokenetwork.ca

- HealthLinkBC, www.healthlinkbc.ca or by telephone (toll free in BC) 8-1-1 or 7-1-1 (for the hearing impaired) for health information, translation services and dieticians.

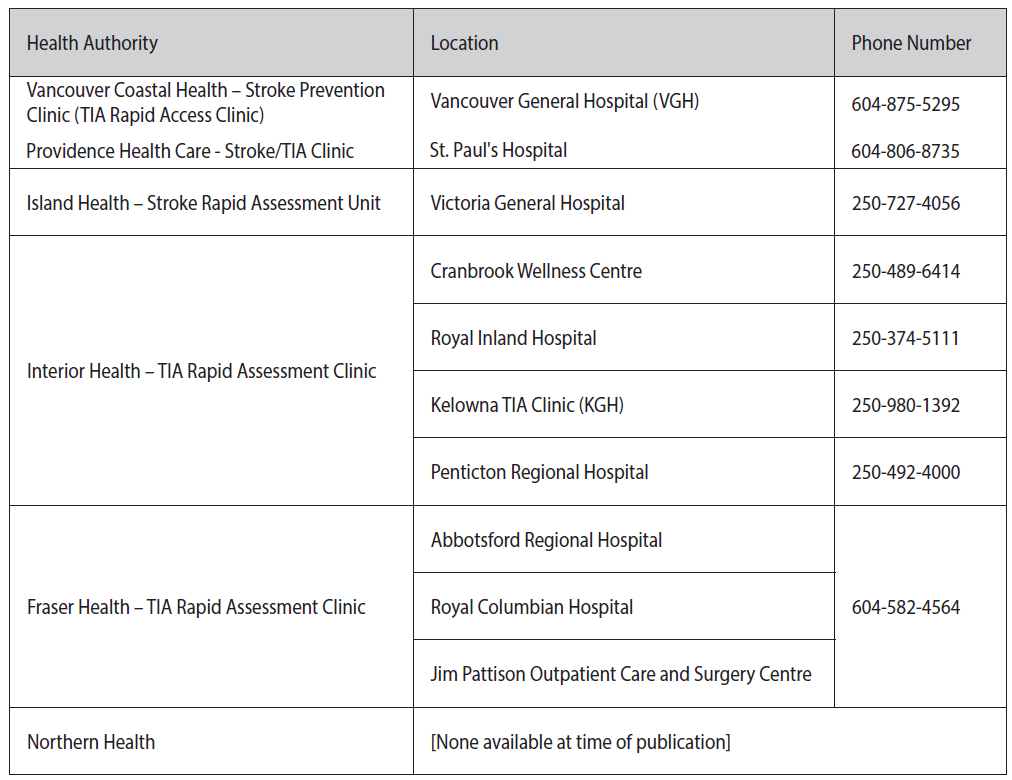

Stroke/TIA Assessment Clinics

Patient Information

- Canadian Stroke Best Practices, www.strokebestpractices.ca, see Patient & Family Tools

Diagnostic Codes: Stroke 434; TIA 435; Intracerebral hemorrhage 431

Appendices

- Appendix A: Cincinnati Stroke Scale

- Appendix B: ABCD2 : To Assess 2-Day Stroke Risk After a TIA

- Appendix C: Prescription Medication Table for Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

- BCGuidelines.ca - Atrial Fibrillation – Diagnosis and Management

- BCGuidelines.ca - Use of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants (NOAC) in Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation

- BCGuidelines.ca - Warfarin Therapy Management

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, approved by the British Columbia Medical Association, and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact InformationGuidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee E-mail: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Web site: www.BCGuidelines.ca |

Disclaimer

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional.

TOP

TOP