Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Diagnosis and Management

Effective Date: January 17, 2024

Revised Date: January 17, 2025 [Minor revisions to reflect PharmaCare regular benefit coverage for Tiotropium]

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Epidemiology

- Definition

- Risk Factors

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Environmental Impact and Climate Change

- Indications for Referral

- Resources

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in primary care.

Key Recommendations

Diagnosis

- Confirm all presumptive, symptom-based diagnoses of COPD one time with spirometry postbronchodilator ratio of FEV1/FVC < 0.7.

- Understand asthma and COPD are distinct diagnoses and may exist in the same patient. [NEW, 2024]

- CT is not needed to diagnose COPD but may be useful for screening lung cancer. [NEW, 2024]

Management

- Encourage all patients who smoke to quit or decrease use as treatment for COPD.

- Manage COPD early in order to slow disease progression. [NEW, 2024]

- Investigate and manage possible comorbidities to optimize outcomes.

- Refer patients, especially those with moderate to severe COPD, to a respiratory therapist for education and/or pulmonary rehabilitation.

- Provide appropriate immunizations to reduce the risk of exacerbation and mortality. [NEW, 2024]

- Consider checking baseline blood eosinophil count prior to commencing inhaled corticosteroid (ICS). [NEW, 2024]

Environmental Impact and Climate Change

- Consider medication options with lower environmental impact. Metered-dose inhalers (MDIs) contribute disproportionately to climate change, which in turn can affect COPD. [NEW, 2024]

- Prepare for climate events such as wildfire and extreme heat, which can exacerbate COPD symptoms. [NEW, 2024]

Education

- Prescribe appropriate controller and rescue medications along with a COPD action plan.

- Evaluate the patient's inhaler adherence and technique regularly.

Definition

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a progressive chronic lung disease, typically caused by emphysema (destruction of alveoli) or chronic bronchitis (inflammation of bronchioles), and is characterized by dyspnea, cough, and sputum production.1 As of 2020/21, more than 5% of those over age 35 have been diagnosed with COPD in BC.2

Symptoms are exacerbated through exposure to viruses, bacteria, and noxious particles or gasses. Patients with acute exacerbations have a notably higher mortality rate than those with stable COPD.3

Risk Factors

Environment

In Canada, 80 to 90% of COPD is caused by smoking.4 Other important risk factors include: occupational exposure to dusts (e.g., coal, grain, wood) or fumes (e.g., natural gas, biofuel), repeated respiratory infections during childhood, history of cooking over an open flame, and a history of exposure to smoke (e.g., wildfires, burn piles, industrialized urban areas) or second-hand smoke.4 The Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) tracks the quality of outdoor air.

Genetics

A genetic deficiency of alpha-1-antitrypsin (A1AT), an anti-protease which protects the lung tissue from damage, is associated with an increased risk of COPD.5 Testing for A1AT deficiency is expensive, low yield, often duplicated and may not alter management in a meaningful way. Therefore, refer patients with high pre-test probability to a specialist.

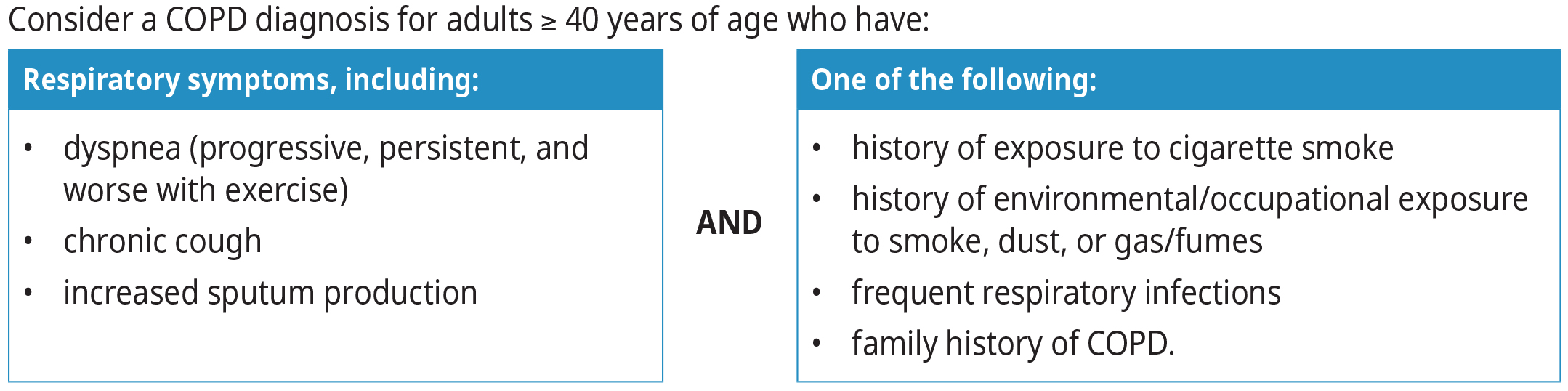

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on a combination of medical history and physical examination and is confirmed through documentation of airflow limitation using spirometry. Confirmation with spirometry is important because COPD is over-diagnosed (59%) when patients are assessed by medical history alone. However, spirometry may be difficult to access.6 If clinically indicated, consider initiating empiric therapy for COPD while awaiting spirometry.

Common differential diagnoses for COPD include asthma (see BCGuidelines.ca: Asthma - Diagnosis, Education, and Management), heart failure (see BCGuidelines.ca: Heart Failure - Diagnosis and Management), restrictive and/or interstitial lung diseases, obesity, and deconditioning.1

Key differences between asthma and COPD are:1

- COPD is diagnosed by post-bronchodilator ratio of Forced Expiratory Volume (FEV1)/ Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) < 0.7

- Asthma symptoms can remain stable or improve on appropriate therapy, while COPD is a progressive condition.

- COPD is typically diagnosed after age 40.

Note that fixed airflow obstruction may be present in both COPD and uncontrolled asthma (see BCGuidelines.ca: Asthma - Diagnosis, Education, and Management).

Previous guidelines have referenced Asthma and COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS). Instead of diagnosing ACOS, it is now recognized that Asthma and COPD may coexist in the same patient.1

Spirometry

Although provincial access may be challenging, it is important to send all patients suspected of having COPD for one-time confirmation of the diagnosis by spirometry. In the case of severe symptoms, referral to a specialist should happen with or without spirometry.

Borderline results may indicate need to consider alternate diagnosis. Consider repeat testing based on changes in clinical presentation.

For spirometry to qualify for coverage under the Medical Services Plan, testing must be performed at an accredited facility. However, evidence suggests that with correct training and equipment, spirometry performed in an office is comparable to testing performed in a pulmonary function laboratory.7

Chest X-ray and CT Scan

Neither chest x-ray nor CT is required for diagnosing COPD.1 CT may be helpful to screen for lung cancer in appropriate patients.

The evidence supporting lung cancer screening with low dose CT exclusively shows benefit for those between age 55-74, with at least a 30-pack year history of smoking and smoking within the last 15 years.8 Encourage selected patients to call the Lung Screening Program (1-877-717-5864) to complete a risk assessment over the phone to confirm their screening eligibility for low dose CT.9,10

Assessment of COPD Severity

Once the diagnosis is confirmed by spirometry, determine the level of COPD severity with a tool such as the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale or the COPD Assessment Test (CAT). These self-administered tools, which can be completed pre-appointment, aid in patient selection, treatment management, and ongoing monitoring.1 See Appendix A: COPD Severity Assessment Scales, for more information.

Management

The therapeutic goals of COPD management include:1

- Decrease mortality

- Decrease complications

- Decrease exacerbations

- Slow or prevent progression

- Increase exercise tolerance

- Increase quality of life

Non-Pharmacological Management

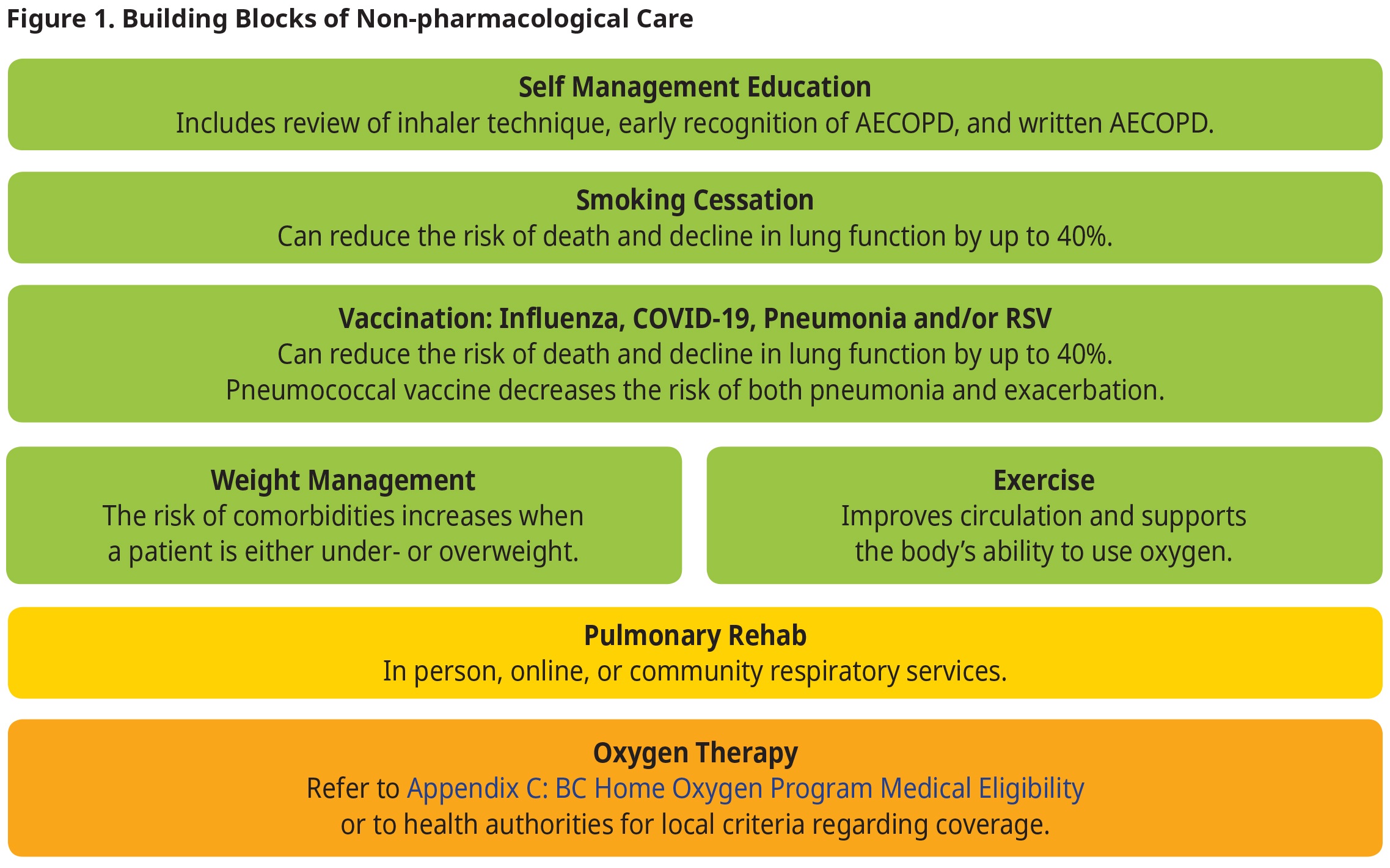

Non-pharmacological therapy is complementary and part of a comprehensive approach to managing COPD.

All patients who smoke and have COPD should be encouraged to quit, as treatment for COPD.

Smoking Cessation resources include:

- QuitNow: quitnow.ca or 1-877-455-2233

- BC Smoking Cessation Program

Provide appropriate immunizations to reduce the risk of exacerbation and mortality11 (i.e., influenza, COVID-19, RSV, and pneumococcal) (see BC CDC’s Vaccines in BC and National Advisory Committee on Immunization’s (NACI) recommendations).

Weight management, and exercise are recommended for all patients with COPD (See Patient, Family and Caregiver Resources).

Refer patients with moderate to severe COPD to pulmonary rehabilitation (See PathwaysBC).

Figure 1. Building Blocks of Non-pharmacological Care

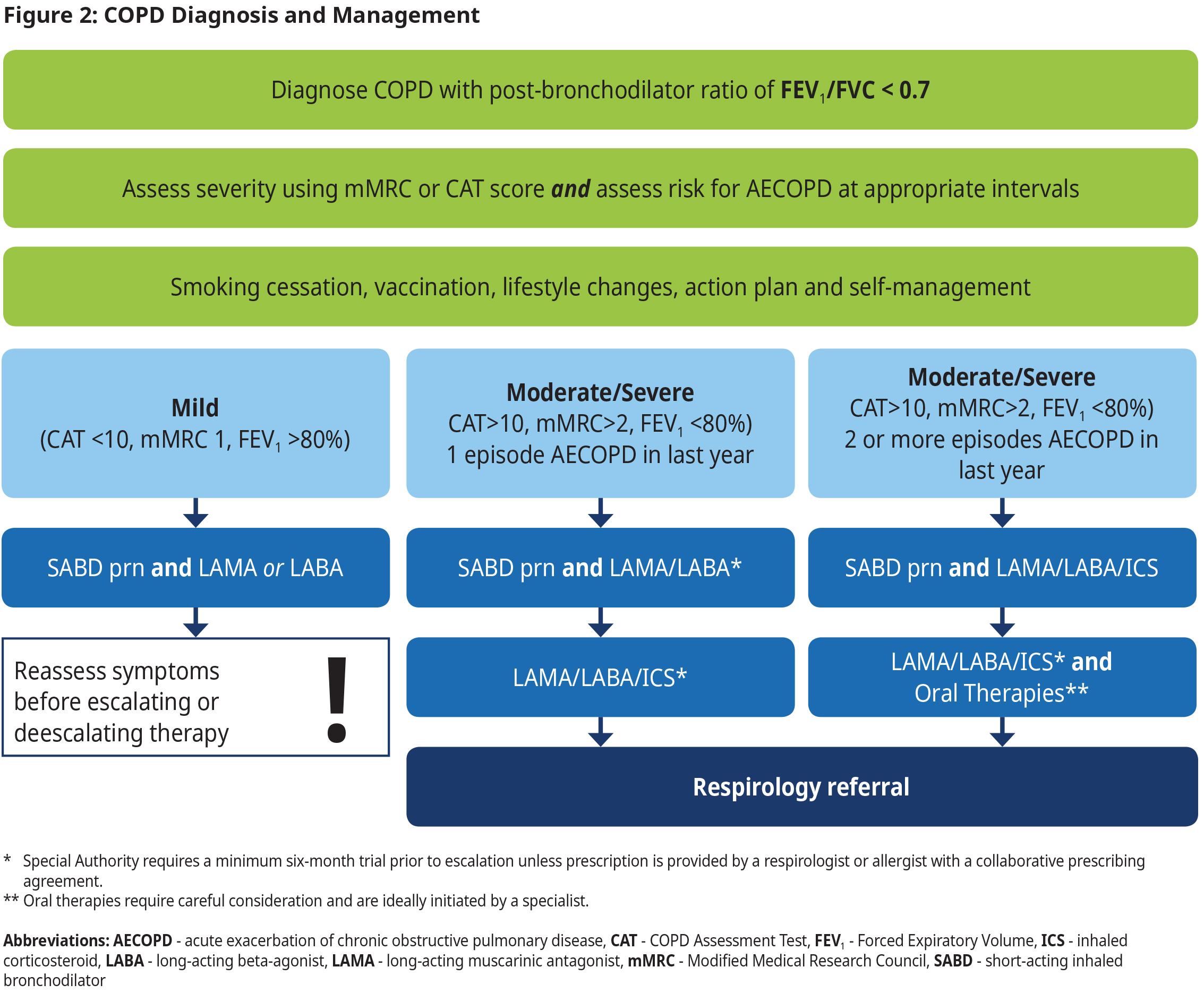

Pharmacological Management

When prescribing medication for patients with COPD:

- Choose medications based on severity.

- Ensure that drug classes are not duplicated.

- Evaluate the patient's adherence and inhaler technique regularly, as up to 50% of patients use their device incorrectly.12,13 Ask pharmacist to demonstrate.

- Prescribe a spacer for metered dose inhalers. Spacer devices (valved holding chamber) must be bought separately; however, spacers make it easier for a patient to use their MDI and they distribute medication to the lungs more proficiently, thereby increasing the effectiveness of medication.

- Consider the patient’s cognitive and physical abilities, ease of device use, convenience, cost, and environmental implications regarding inhaler choices.14

- Individualize therapy at all times. For patients who could benefit from enhanced adherence and reduced inhaler technique errors, it is worth considering a single inhaler containing multiple medications instead of using multiple inhalers with a single medication in each.

Figure 2

Inhaled Corticosteroid Steroids (ICS) and Eosinophils

An ICS is typically added to a medication regimen last, due to an increased risk of pneumonia.15

The use of blood eosinophil counts to help guide therapy with ICS for patients with exacerbations is an emerging practice.16 A high eosinophil count (>0.3 x 109/L) indicates a patient will likely respond well to ICS treatment, resulting in fewer acute exacerbations. In contrast, a low blood eosinophil count (<0.1 x 109/L) indicates a patient is less likely to benefit from ICS treatment.1 Low eosinophil count is also associated with an increased risk of pneumonia for patients.1

If used, a blood eosinophil count should be measured prior to commencing treatment with an ICS, and when the patient is neither in an acute exacerbation nor on an oral steroid.

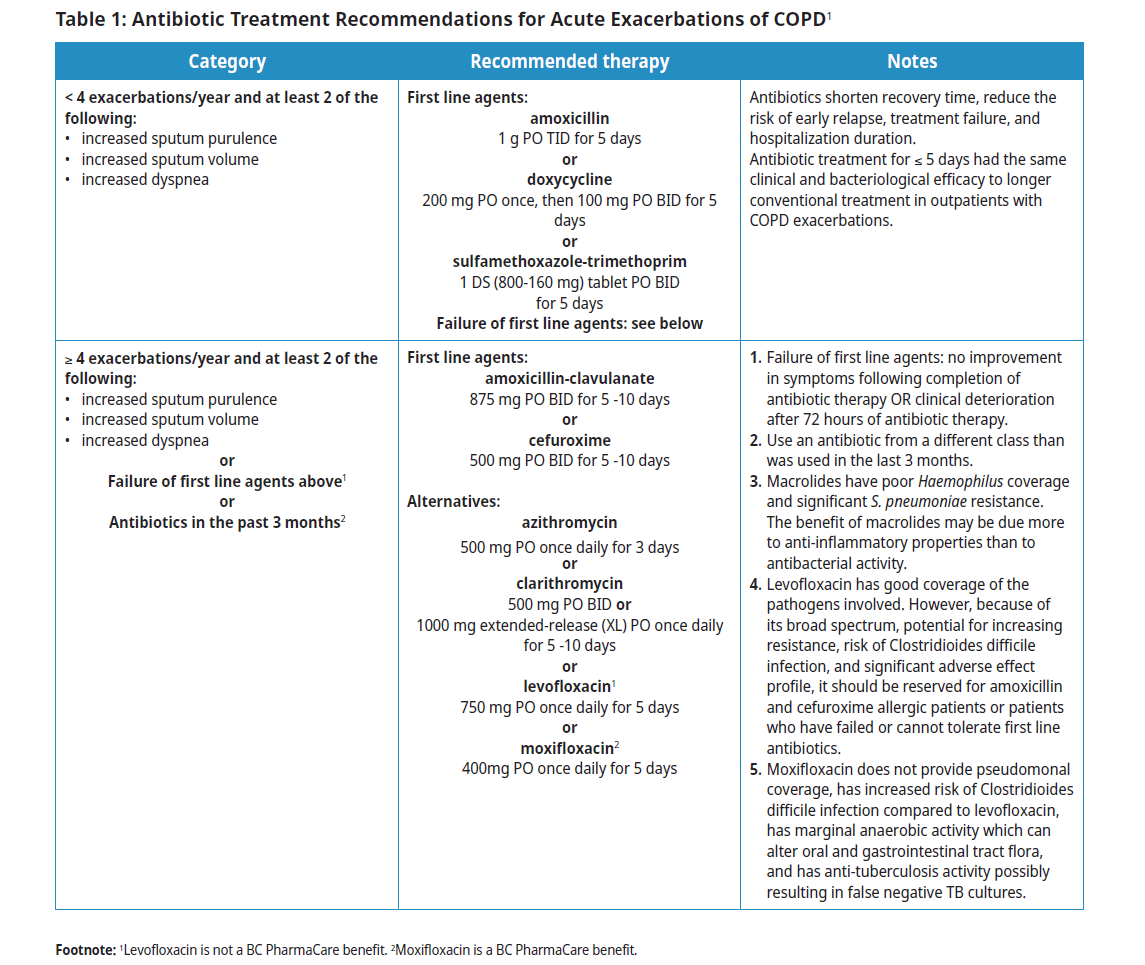

Treatment of Acute Exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD)

AECOPD is characterized by (48 hours or more) of worsening dyspnea, increased coughing, and usually increased sputum volume or purulence. The most common cause is a viral or bacterial infection. Non-infectious causes include noxious particles (e.g., forest fire smoke). Differential diagnoses include pneumonia, pleural effusion, heart failure exacerbation, pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax. Patients who experience COPD exacerbations have a significantly higher mortality rate than those with stable COPD.1 This mortality risk increases with the number of exacerbations. Develop an exacerbation action plan with patients (see Associated Document: COPD Flare-up Action Plan (PDF, 67KB)).

More than 80% of exacerbations can be managed on an outpatient basis with pharmacologic therapies (typically, systemic corticosteroids are indicated – see Table 1: Antibiotic Treatment Recommendations for Acute Exacerbations of COPD).1 Severe AECOPD complicated by acute respiratory failure is a medical emergency and should be assessed in acute care.

Pharmacologic therapies for AECOPD may include:

- Short-acting bronchodilator for initial treatment of acute exacerbation.

- Oral corticosteroids for most moderate to severe COPD patients1 • Evidence suggests that systemic corticosteroids in AECOPD shorten recovery time, improve lung function and oxygenation, and reduce the risk of early relapse, treatment failure, and duration of hospitalization.1,17

- A well-powered, randomized controlled trial comparing 5 versus 14 days of oral corticosteroids showed similar efficacy.18 40 mg prednisone-equivalent per day for 5 days is recommended.1 In practice, taking a single 50 mg tablet is easier for patients than taking 8X 5 mg tablets. For most patients, based on the trial above, tapering the corticosteroid dose should not be necessary.

- Systemic corticosteroids have not been shown to reduce AECOPD beyond the initial 30 days of an exacerbation. Long-term use of systemic corticosteroids is not recommended as the risk of adverse events far outweighs any potential benefits.

- Antibiotic treatment (see Table 1: Antibiotic Treatment Recommendations for Acute Exacerbations of COPD).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some patients used pulse oximeters (POs) to monitor the severity of their respiratory disease. While at-home PO may be one option to monitor changes to lung function, they are not always reliable, particularly those in fitness watches. Interpret at-home PO with caution.

Environmental Impact and Climate Change

COPD and Climate Events

Severe climate events such as extreme heat and wildfire, increase likelihood of developing COPD and increase the risk of pneumonia, acute exacerbations, emergency room visits, hospital admissions, ICU admissions requiring ventilation, and death in patients with COPD. Patients with COPD are encouraged to review information on extreme climate risks and how to manage them in Patient Handout: COPD and the Environment (PDF, 19KB).

HEPA filters in patients with moderate to severe COPD

In a high-quality placebo-controlled RCT, use of HEPA and carbon filter air cleaners improved symptoms, reduced moderate exacerbations, and lowered rescue inhaler use (a well-studied marker of disease control).19 Encourage patients with moderate to severe COPD to incorporate appropriate air filters at home.

Environmental Considerations for Inhalers

Dry Powder Inhalers (DPIs)

DPIs rely on the force a patient generates to inhale their medication rather than on a propellant, which makes them a more environmentally friendly option. DPIs are not recommended for patients with very poor inspiratory capacity such as those with end-stage COPD or neuromuscular weakness.

Metered Dose Inhalers (MDIs)

MDIs rely on a propellant to distribute medication. The propellant is a liquefied, compressed gas called hydrofluoroalkane (HFA). HFAs have been identified as a gas with “a high global warming potential”.20 One brand of salbutamol inhaler generates the same carbon emissions per inhaler as driving a car 113 km, while a different brand of the same medication, with the same coverage, generates the same carbon emissions per inhaler as driving a car 38.8km.21 Not all MDIs have the same quantity of HFA. The leaf icon in Appendix B: COPD Medication Table indicates lower carbon footprint medication options. While not all patients are candidates for lower-HFA alternatives, transitioning those who do qualify has the potential to significantly impact the negative climate-inhaler cycle.

Ongoing Management

Follow-up Care

Modify therapeutic goals and management plans as appropriate. Use routine follow-ups to ask about and monitor the patient’s key clinical indicators, including:

- Spirometry values*

- Changes in symptoms

- mMRC and/or CAT score

- Exacerbation history and review of the Flare-Up Action Plan

- Management of comorbidities

- Pharmacologic therapy adherence

- Inhaler technique

- Goals of care (Flare-Up Action Plan)

*Following major changes and/or after recovery from a severe exacerbation or hospitalization.

Deprescribing ICS

ICS may increase the risk of pneumonia. If a patient is stable, weigh the patient’s risk of pneumonia against their risk of exacerbation.1 Consider how removal of ICS would impact exacerbation risk and financial cost for patients.

Indications for Referral

Refer patient to a specialist in cases where:

- the diagnosis remains uncertain

- a patient is < 40 years with fixed airflow obstruction/COPD and limited smoking history

- suspected A1AT deficiency (e.g., early age of onset, unexplained liver disease, family history)

- there are severe or recurrent exacerbations (more than one per year) despite triple therapy and smoking cessation

- there are numerous comorbidities requiring more intensive assessment and management when considering additional therapies beyond combination inhalers

- a patient is frail and may benefit from comprehensive geriatric assessment

The Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise (RACE) website, app, and phone line provides access to specialists for urgent advice. Clinicians from BC can access PathwaysBC for patient education materials, clinical referral forms, and more.

RACE is available Monday to Friday from 8:00AM to 5:00PM.

Vancouver: 604-696-2131

Toll Free: 1-877-696-2131

Controversies of Care

Vaping

The Canadian Lung Association and the Canadian Thoracic Society have issued a collaborative position statement on vaping, asserting vaping presents risks for more nicotine dependency, and risks to lung and overall health.22

Some individuals use e-cigarettes as cessation aids, and some studies support this approach,23,24 although vaping has not been proven as a smoking cessation aid.25 Primary care physicians should be very cautious supporting patients’ use of e-cigarettes as a cessation aid.

Dual vs. Triple Therapy

Dual therapy combines the use of two drugs, while triple therapy combines three drugs. Triple therapy is associated with reduced exacerbations and fewer hospitalizations for patients with moderate to severe COPD, but it is also associated with increased side effects (e.g., pneumonia).1,26 Uncontrolled symptoms, increased CAT scores, and exacerbations are indicators a patient may benefit from triple therapy.

In BC, escalation from dual to triple therapy (in a single inhaler) is limited coverage, with criteria being that a patient has an inadequate response after a minimum 6-month trial of dual therapy before being eligible for triple therapy coverage through their primary care provider. For more information on medication coverage, see Appendix B: COPD Medication Table.

ETHOS and IMPACT Trials and Mortality

The ETHOS (Efficacy and Safety of Triple Therapy in Obstructive Lung Disease) and IMPACT (Informing the Pathway of COPD Treatment) trials suggested that triple therapy (a combination of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) and long-acting beta agonists (LABA) given in a single inhaler) may reduce mortality compared with dual bronchodilation.26,27 These trials are hypothesis-generating as the steadily increasing focus on outcomes such as all cause mortality reduction has gained recognition from GOLD and CTS guidelines. However, neither study was designed with all-cause mortality (ACM) as a primary end point but showed results that need to be investigated in future trials to validate the findings on mortality reduction.

Resources

Abbreviations

A1AT

AECOPD

CAT

COPD

DPI

FEV1

ICS

LABA

LAMA

MDI

mMRC

SABD

SAMA

alpha-1 antitrypsin

acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder

COPD Assessment Test

chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder

dry powder inhaler

Forced Expiratory Volume

inhaled corticosteroid

long-acting beta-agonist

long-acting muscarinic antagonist

Metered dose inhaler

Modified Medical Research Council

short-acting inhaled bronchodilator

short-acting muscarinic antagonist

Practitioner Resources

- UBC CPD Module on COPD: Module on COPD Initial & Ongoing Assessment available at: elearning.ubccpd.ca/enrol/index

- RACE Line: Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise Program: a phone app for physicians, nurse practitioners and medical residents. raceconnect.ca/

- PathwaysBC: An online resource that allows GPs and nurse practitioners and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. See: https://pathwaysbc.ca/login

- Health Data Coalition: An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist you in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing. See: Health Data Coalition – Better Information. Better Care. Better Patient Outcomes. (hdcbc.ca)

- Family Practice Services Committee: https://fpscbc.ca/

Practice Support Program: offers focused, accredited training sessions for BC physicians to help them improve practice efficiency and support enhanced patient care. - Creating A Sustainable Canadian Health System In A Climate Crisis (CASCADES):

- Primer - Inhalers

- Inhaler Coverage Reference Chart o Patient Inhaler Disposal Poster o Patient-Facing Inhaler Infographic

Above resources available at: https://cascadescanada.ca/resources/sustainable-inhaler-prescribing-in-primarycare-playbook/

- BC Ministry of Health – Advance Care Planning: www.gov.bc.ca/advancecare In addition, each health authority also has an Advance Care Planning website.

Patient, Family and Caregiver Resources

- Quit Smoking: It provides one-on-one support and valuable resources in multiple languages to help you plan your strategy and connect with a Quit Coach. See: Community and Support | QuitNow. Phone: 1-877-455-2233 (toll-free) Email: quitnow@bc.lung.ca

- Smokers’ Helpline at 1-866-366-3667 or visit Home (smokershelpline.ca)

- HealthLink BC: You may call HealthLinkBC at 8-1-1 toll-free in B.C., or for the deaf and the hard of hearing, call 7-1-1. You will be connected with an English-speaking health-service navigator, who can provide health and health-service information and connect you with a registered dietitian, exercise physiologist, nurse, or pharmacist. See: healthlinkbc.ca/ for several resources such as:

- Island Health Community Virtual Care: Community Virtual Care provides support to people with a range of medical conditions. Registered nurses help you to manage your condition from the comfort of your home. All the tools needed are loaned to you at no cost.

- BC Caregiver Support Line: Call our toll-free BC Caregiver Support Line at 1-877-520-3267, 8:30 am – 4:00 pm PT, Monday to Friday. FCBC staff are experienced in dealing with caregiver situations. We take time to listen to you which distinguishes us from the busy health care providers you may encounter. We are then able to offer help with:

- Information and referral to resources

- Healthcare navigation

- Emotional support

- Access to support groups

- Access to webinars, articles, and resources specific to your needs

- Self-ManagementBC: https://www.selfmanagementbc.ca/home Offers FREE health programs for adults of all ages with one or more ongoing health conditions. Programs are offered in person, virtually, online, by telephone, or by mail for adults living in BC.

- BC Lung Foundation: https://bclung.ca/patient-support/copd-resources

- Creating A Sustainable Canadian Health System In A Climate Crisis (CASCADES):

- Canadian Lung Association

- How to use your inhaler (video): https://www.lung.ca/lung-health/how-use-your-inhaler

- American Lung Association

- Better Breathers Club: Support groups for individuals with chronic lung disease and their caregivers. Learn better ways to cope with conditions such as COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, and asthma while getting the support of others in similar situations. Led by a trained facilitator, these online adult support groups give you the tools you need to live the best quality of life you can.

Diagnostic Codes

- Chronic bronchitis (491)

- Emphysema (492)

- Bronchiectasis (494)

- Chronic airways obstruction-not elsewhere classified (496)

Billing Codes

- FFS: PG14053 annual CDM payment billable after one year of care has been provided including at least two FFS visits as per fee notes.

- LFP: Patient interaction codes in addition to daily direct and indirect time with annual complexity management included in panel payments.

Appendices

- Appendix A: COPD Severity Assessment Scales

- Appendix B: COPD Medication Table

- Appendix C: BC Home Oxygen Program Medical Eligibility

Associated Documents

- Patient Handout: COPD and the Environment (PDF, 19KB)

- COPD Flare-up Action Plan (PDF, 67KB)

- Patient Care Flow Sheet (PDF, 424KB)

- List of Contributors (PDF, 164KB)

References

- Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2023. [Internet]. Available from: Available from: http://goldcopd.org/.

- British Columbia Ministry of Health [data provider]. BC Observatory for Population and Public Health [publisher]. Chronic Disease Dashboard. Available at: http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/disease-system-statistics/chronic-disease-dashboard.

- Soler-Cataluña JJ, Martínez-García MA, Román Sánchez P, Salcedo E, Navarro M, Ochando R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005 Nov;60(11):925–31.

- Government of Canada. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) [Internet]. 2019. [Internet]. Available from: Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/ public-health/services/chronic-diseases/chronic-respiratory-diseases/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd.html%205

- Torres-Durán M, Lopez-Campos JL, Barrecheguren M, Miravitlles M, Martinez-Delgado B, Castillo S, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: outstanding questions and future directions. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018 Jul 11;13(1):114.

- Nardini S, Annesi-Maesano I, Simoni M, Ponte AD, Sanguinetti CM, De Benedetto F. Accuracy of diagnosis of COPD and factors associated with misdiagnosis in primary care setting. E-DIAL (Early DIAgnosis of obstructive lung disease) study group. Respir Med. 2018 Oct;143:61–6.

- Langan RC, Goodbred AJ. Office Spirometry: Indications and Interpretation. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Mar 15;101(6):362–8.

- New lung cancer screening guideline – Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 9]. Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/ new-lung-cancer-screening-guideline/

- BC Cancer Lung Screening Program—first of its kind in Canada | British Columbia Medical Journal [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 9]. Available from: https://bcmj.org/ blog/bc-cancer-lung-screening-program-first-its-kind-canada

- Who Should Be Screened? [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 9]. Available from: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/lung/get-screened/who-should-be-screened

- Simon S, Joean O, Welte T, Rademacher J. The role of vaccination in COPD: influenza, SARS-CoV-2, pneumococcus, pertussis, RSV and varicella zoster virus. Eur Respir Rev [Internet]. 2023 Sep 30 [cited 2023 Dec 8];32(169). Available from: https://err.ersjournals.com/content/32/169/230034

- Molimard M, Raherison C, Lignot S, Balestra A, Lamarque S, Chartier A, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation and inhaler device handling: real-life assessment of 2935 patients. Eur Respir J. 2017 Feb;49(2):1601794.

- Kaplan A, Price D. Matching Inhaler Devices with Patients: The Role of the Primary Care Physician. Can Respir J. 2018 May 23;2018:9473051.

- Usmani OS. Choosing the right inhaler for your asthma or COPD patient. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019 Mar 14;15:461–72.

- Iannella H, Luna C, Waterer G. Inhaled corticosteroids and the increased risk of pneumonia: what’s new? A 2015 updated review. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016 Jun;10(3):235–55.

- Ashdown HF, Smith M, McFadden E, Pavord ID, Butler CC, Bafadhel M. Blood eosinophils to guide inhaled maintenance therapy in a primary care COPD population. ERJ Open Res. 2021 Feb 7;8(1):00606–2021.

- Walters JA, Tan DJ, White CJ, Gibson PG, Wood‐Baker R, Walters EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2023 Nov 28];(9). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001288.pub4/full

- Leuppi JD, Schuetz P, Bingisser R, Bodmer M, Briel M, Drescher T, et al. Short-term vs Conventional Glucocorticoid Therapy in Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The REDUCE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2013 Jun 5;309(21):2223–31.

- Halpin DMG, Rothnie KJ, Banks V, Czira A, Compton C, Wood R, et al. Comparative Adherence and Persistence of Single- and Multiple-Inhaler Triple Therapies Among Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in an English Real-World Primary Care Setting. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:2417–29.

- Jeswani HK, Azapagic A. Life cycle environmental impacts of inhalers. J Clean Prod. 2019 Nov 10;237:117733.

- Climate impact of inhaler therapy in the Fraser Health region, 2016–2021 | British Columbia Medical Journal [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 8]. Available from: https://bcmj.org/articles/climate-impact-inhaler-therapy-fraser-health-region-2016-2021

- Canadian Lung Association, Canadian Thoracic Society. E-cigarettes in Canada: The Canadian Lung Association and The Canadian Thoracic Society are issuing a collaborative statement calling for critical measures, by all levels of government, to effectively regulate vaping such that young people are protected, health effects are monitored, and research on potential for smoking cessation is enhanced. Breathe: The Lung Association [Internet]. Available from: https://www.lung.ca/news/position-statement-vaping.

- Hartmann-Boycea J, Lindsona N, Butler AR, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Begh R, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 10];(11). Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub7/full

- Grabovac I, Oberndorfer M, Fischer J, Wiesinger W, Haider S, Dorner TE. Effectiveness of Electronic Cigarettes in Smoking Cessation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res Off J Soc Res Nicotine Tob. 2021 Mar 19;23(4):625–34.

- Al-Hamdani M, Manly E. Smoking cessation or initiation: The paradox of vaping. Prev Med Rep. 2021 Mar 23;22:101363.

- Soumagne T, Zysman M, Karadogan D, Lahousse L, Mathioudakis AG. Impact of triple therapy on mortality in COPD. Breathe Sheff Engl. 2023 Mar;19(1):220260.

- Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Ferguson GT, Wedzicha JA, Singh D, Wang C, et al. Reduced All-Cause Mortality in the ETHOS Trial of Budesonide/Glycopyrrolate/Formoterol for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter, Parallel-Group Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Mar 1;203(5):553–64.

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the effective date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee in collaboration with the Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services and adopted under the Medical Services Act and the Laboratory Services Act

|

Disclaimer

The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the guidelines) have been developed by the guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional.

TOP

TOP