Cervical Cancer Prevention and Screening

Effective Date: April 17, 2025

Revised: August 31, 2025 (Minor updates to reflect changes in HPV9 vaccine dose schedule recommendations and BC program eligibility.)

Revised: December 3, 2025 (Minor updates to reflect terminology in discussing HPV test results with patients.)

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Background

- Definitions

- Epidemiology

- Etiology

- Risk factors

- Prevention

- Immunization

- Screening

- Eligibility

- Test Types and Sample Collection Methods

- Screening Results and Follow-Up

- Screening Frequency

- Cessation of Screening

- Barriers to Participation

- Other Clinical/ Special Considerations

- Resources

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for cervical cancer screening in asymptomatic patients without a history of cervical cancer who are or have been sexually active. Screening information applies to individuals who have or have had a cervix. This includes women and Two-Spirit, Transgender, and Gender-diverse (TTGD) people. The guideline also provides recommendations for prevention of cervical cancer, including immunization for all individuals.

This guideline does not address investigation or management for symptomatic patients beyond referral for colposcopy or other human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers in sites outside the cervix.

This guideline was developed in consideration of the BC Lifetime Prevention Schedule, In Plain Sight Report, and Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Calls to Action and is consistent with the BC Cancer Cervix Screening Program information.

Key Recommendations

- Ensure all eligible individuals are immunized against HPV. Refer to he BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) for specific program information, including grade 6 school immunizations, and July 2025 program changes to expand eligibility and update dose schedule recommendations.

- Ensure all asymptomatic patients aged 25-69 without a history of cervical cancer are screened every 3-5 years, depending on clinical history and screening method. Note that screening is indicated for those > 69 years of age if they are immunocompromised or were recently discharged from colposcopy and have not had a cervical liquid based cytology (LBC) sample with a negative co-test result in the previous 12 months.

- Choose a screening and sam ple collection method based on patient scenario and preferences. Note that screening with a self-collected vaginal sample is as effective as screening undertaken with a provider-collected sample from the cervix.1–5

- Vaginal Swab for HPV Testing – Collected by patient (self-screening) or provider

-

LBC Sample for HPV and/or Cytology – Collected by provider

- Do not perform cervical cancer screening as a part of routine pre-natal screening. This is only indicated if the patient is due or overdue. If screening is to be done during pregnancy, self-screening is not recommended and instead the provider should collect a cervical LBC sample or vaginal HPV swab.

- Investigate/manage all symptomatic patients following best practices for symptom evaluation, including a speculum examination.

- If any suspicious abnormality is identified during speculum examination, collect a cervical LBC sample for a co-test (HPV and cytology). Initiate an urgent referral for colposcopic evaluation, without waiting for test results.

-

A vaginal sample for HPV testing alone is not appropriate for symptomatic patients.

- Screen all patients according to program guidelines, paying particular attention to patients with risk factors or those facing barriers to participation to encourage optimal alignment with screening protocols.

- Provide patient education regarding cancer screening, including implications of test results.

- Incorporate a trauma informed and culturally safe approach for all patients.

- Ensure appropriate longitudinal care interactions for patients who were previously accustomed to having a Papanicolaou (Pap) appointment every three years.

Background

BC Cancer leads publicly funded cancer screening programs for asymptomatic individuals. Historically, cervix screening was done using a conventional cytology Pap smear to detect precancerous lesions. While very specific (96.8%), Pap smears suffer from low sensitivity (55.4%).6,7 In 2022, BC changed to liquid-based cytology (LBC) collection. LBC samples can be used for cytology, HPV testing or both.

Regular screening reduces the incidence of stage 1A cervical cancer by 67% and stage 3 or worse by 95%.8 In BC, 66% of patients with squamous cell carcinoma and 46% of patients with adenocarcinoma cervical cancer had either never been screened or did not receive timely screening.9 Unfortunately, only 68% of eligible patients have had a cytology screen in the preceding 42 months.10

In 2024, BC began transitioning to an HPV primary population-based screening program. Research indicates that when HPV DNA testing is used alone or in combination with cytology, there is earlier and enhanced detection of pre-cancerous lesions and a reduction in subsequent cancerous lesions.1,11 HPV testing is also more reliable, can be done less frequently, and has options for patients to collect their own samples. This makes program participation more accessible and convenient for patients across BC, particularly when access to a primary care provider to collect a cervical sample can be a challenge. This represents a significant change for health care providers and patients.

Definition12

- Average Risk: Individuals who are not immunocompromised, who have not been exposed in utero to DES and who have not had a cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2, CIN 3, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), or cervical cancer diagnosis.9

- Cervical Dysplasia: A premalignant condition characterized by abnormal cell growth on the cervix. Two classification systems are used to describe the degree of abnormality:

- High grade SIL (HSIL) – Proliferation of abnormal cells extends from two-third to full thickness of epithelium. Includes CIN 2, CIN 3.2

- Co-test: When an LBC sample undergoes both HPV and cytology testing.

- High Risk: Individuals who are immunocompromised, who have been exposed in utero to DES and who have had a CIN 2, CIN 3, AIS, or cervical cancer diagnosis.

- Liquid-Based Cytology (LBC): Cells from the cervix are collected using a spatula and/or cytobrush that are then transferred into a container with an alcohol-based fixative. The liquid-based sample is submitted to the laboratory and can be used for cytology, HPV testing or both, depending on the indication and testing algorithm.

- Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM): Screening test result indicating no evidence of abnormal cells or malignancy.

- Reflex Test: When the result of the primary test necessitates secondary testing. For example, cervical LBC sample is first assessed for HPV, which is positive. The same sample will then be assessed for cytology. Reflex testing is done automatically by the lab based on triage protocols.

Epidemiology

Cervical cancer is the third most frequently identified cancer and fourth leading cause of cancer-related fatalities in females globally.2,13 One in 170 BC females is expected to develop cervical cancer, while one in 530 will die from it.10,14 Most are diagnosed before the age of 50.15

Studies in BC have shown higher rates of invasive cervical cancer in patients who self-identify as Indigenous, current smokers, from rural areas of the province, or a visible minority.16 Cervical cancer incidence rates are 1.6x higher in First Nations peoples in BC compared to non-First Nations peoples.17,18

Etiology

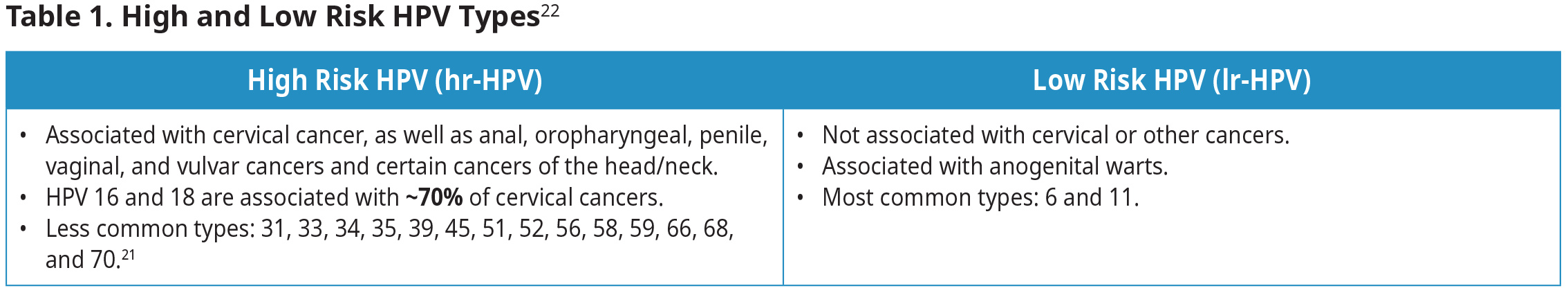

A persistent infection with a high-risk HPV virus (hr-HPV) accounts for >99% of invasive cervical cancer.19,20 Among the >100 known HPV genotypes, some are categorized as hr-HPV.21 The remaining HPV genotypes are categorized as low-risk (lr-HPV), often causing non-cancerous conditions such as warts. See Table 1: High and Low Risk HPV Types22.

HPV is transmitted through epithelial-to-epithelial (skin or mucosa) sexual contact.13 Though less common, it can also be transferred to newborns before or during childbirth.2,13 However, HPV infections in newborns are generally transient and clear within six months.23 Refer to Perinatal Services BC for information on evidence-based practice standards for perinatal health care.

Risk Factors

Over 99% of cervical cancer is related to a persistent infection with high-risk HPV, with HPV-16 and HPV-18 responsible for 70% of these cancers.2,19 HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) and affects >70% of sexually active Canadians.13 Individuals are at greatest risk for an HPV infection in the 5-10 years following their first sexual experience.26

Other risk factors for cervical cancer include immunosuppression, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, multiparity, becoming sexually active at a young age, having many sexual partners or a partner with a history of many sexual partners, history of other STIs, and DES exposure in-utero (note: DES not commonly used in Canada after 1980).2,9,13,27 Oral contraceptive use >5 years also increases the risk of cervical cancer, though this risk decreases after discontinuing use and is neutralized within 10 years.27,28 Importantly, current and former smoking of commercial tobacco exacerbates the risk of cervical cancer by promoting hr-HPV oncogene expression, causing DNA damage, and impairing immune responses, which can facilitate the persistence and progression of HR-HPV infections to malignancy.29,30

Prevention

Cervical cancer is best prevented through HPV immunization. Early detection through screening and adherence to diagnostic/follow-up/management recommendations for pre-cancerous lesions are highly effective secondary prevention measures.2

Other prevention strategies include smoking cessation, education on HPV transmission, and avoiding an HPV infection through safe sexual behaviours, including correct condom use.2

Immunization

Immunization is strongly recommended for all eligible individuals. HPV vaccines are extremely safe and highly effective in preventing HPV infections and cervical cancer.26,31 Immunization is best initiated at younger ages and prior to exposure to HPV.32 However, vaccines are still effective in older populations and for preventing recurrence in patients previously treated for cervical dysplasia. Presently, there is no difference in screening recommendations between immunized and unimmunized individuals.

At this time, there are 2 HPV vaccines approved by Health Canada: HPV2 (Cervarix®) and HPV9 (Gardasil®9).33 HPV9 is recommended because it provides protections against more types of HPV.33 Health Canada’s approval notes HPV9’s indication for the prevention of HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, and 58 in “girls and women 9 through 45 years of age” and “boys and men 9 through 26 years of age”.34,35 These vaccines are >98% effective in preventing HPV 16- or 18-related CIN2/3 or AIS.36,37 See Appendix A for more information on approved vaccines and their coverage in BC. Note that the BCCDC does not currently recommend HPV vaccines for pregnant people. Refer directly to the BCCDC as these recommendations may change based on updates to the Canadian Immunization Guide.

Beginning in 2008, BC implemented publicly funded HPV Immunization with HPV4 (Gardasil®, 4 strains of HPV: 6, 11, 16, and 18;)38 for girls in grades 6 with a 3-year catch-up for girls in grade 9 to cover those born from 1994 onward. In 2016, HPV9 (5 additional strains of HPV: 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) replaced HPV4 for girls in grade 6 (birth year cohort 2005). HPV immunization was expanded in 2017 to include grade 6 boys (birth year cohort 2006).39

BC data 58-60% of grade 6 and 70-74% of grade 9 students have received the HPV vaccine.40,41 BC immunization rates are lower in areas with materially- or socially-deprived neighbourhoods, rural communities, independent schools, and visible minorities.40

The HPV9 vaccine is routinely offered for free to all grade 6 students through school-based immunization clinics with catch-up in other grades. Patients can also access it through various community-based settings (e.g., local pharmacies, First Nations community health clinics or nursing stations, etc.). HPV9 is publicly funded for the following BC residents but private pay is available at most pharmacies and travel clinics for those not covered below:42

- 9-26 years of age (inclusive)

- 27-45 years of age (inclusive) who self-identify as belonging to the gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) community, including, Two-Spirit, transgender, and/or non-binary people (including those who are not yet sexually active and/or questioning their sexual orientation)

- 9-45 years of age (inclusive) living with HIV

- Who received post-colposcopy treatment for cervical dysplasia on or after July 31, 2025

In July 2025, the recommended HPV9 dose schedule changed to include a single-dose schedule for many patients.42 This is a shift in practice for providers. See below for current recommendations and refer to this BCCDC Q&A for more detail about the program change.

- Immunocompetent individuals 9-20 years of age (inclusive): 1 dose given as 0.5 mL IM

- Immunocompetent individuals 21-45 years of age (inclusive): 2 doses given as 0.5 mL IM at 0 and 6 months

- Immunocompromised individuals 9-45 years of age (inclusive): 3 doses given as 0.5 mL IM at 0, 2, and 6 months

- Individuals 9-45 years of age (inclusive) living with HIV: 3 doses given as 0.5 mL IM at 0, 2, and 6 months

- Individuals post-colposcopy treatment: 3 doses given as 0.5 mL at 0, 2, and 6 months

Provide culturally safe and trauma informed patient education about the benefits of immunization. Ask patients about their vaccination status to determine whether they were vaccinated with HPV4 (i.e., prior to 2016) as they may want to consider increasing their protection with HPV9.

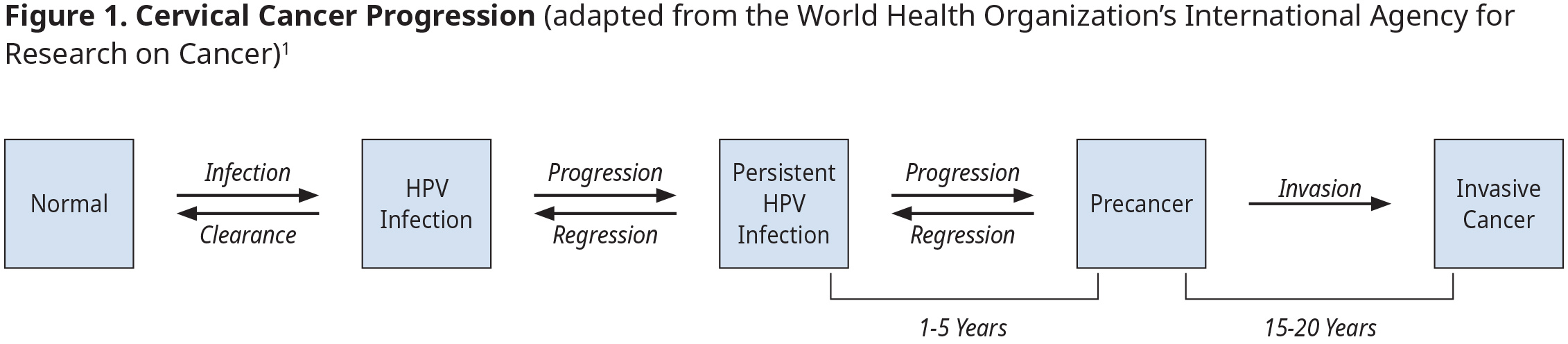

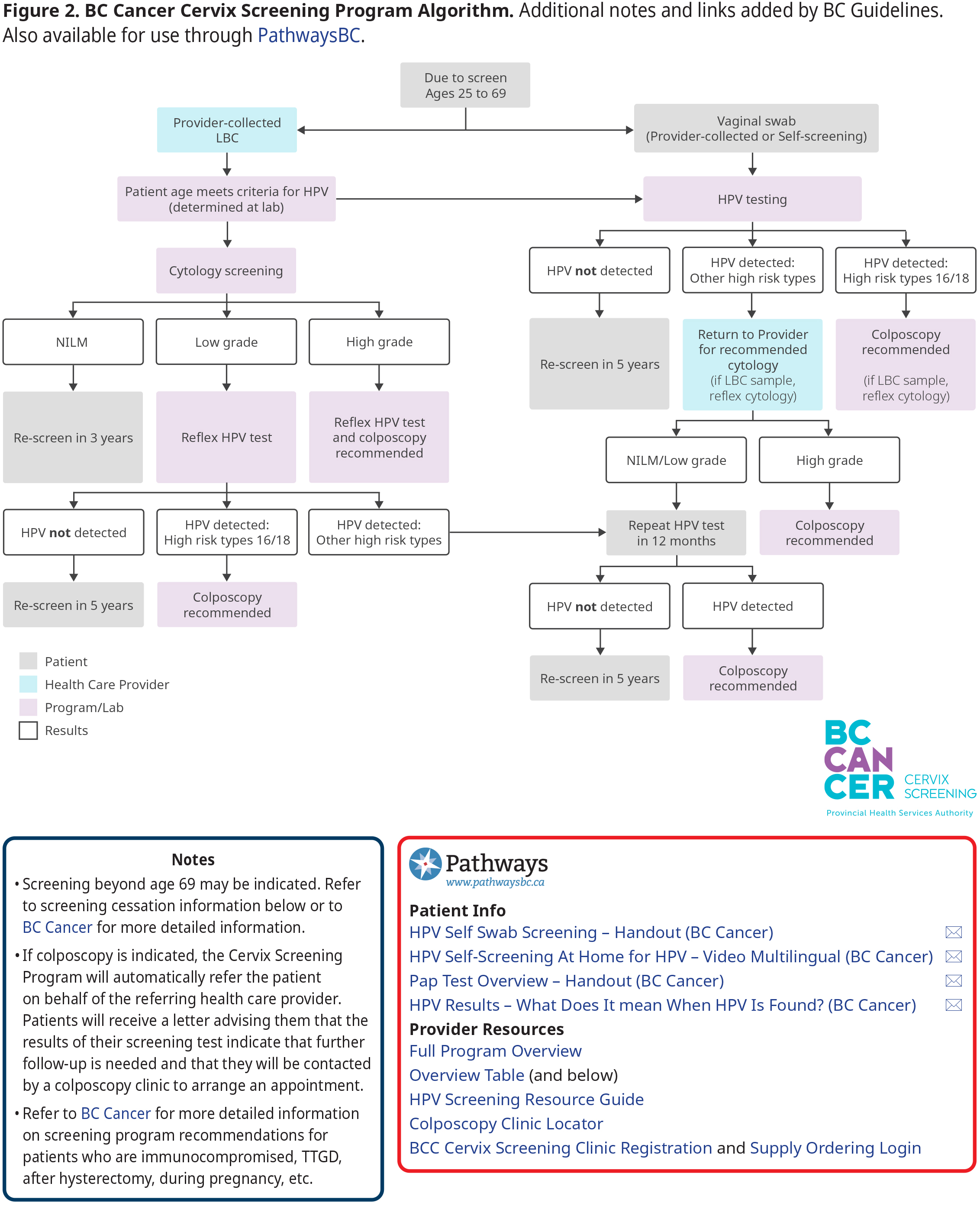

Screening

The purpose of screening is to identify and address cervical cancer precursors to prevent progression, and to detect asymptomatic cases at an early stage, thereby reducing the risk of advanced cancer, complications and death. Refer to Figure 2: BC Cancer Cervix Screening Program Algorithm below for a program overview. Additional detail regarding screening for unique patient scenarios (e.g., after hysterectomy, TTGD, DES exposure in utero, etc.) is available on the BC Cancer website.

While all eligible patients should be screened regularly, pay particular attention to patients with risk factors or those facing barriers to participation to encourage optimal alignment with screening protocols. Provide culturally safe and trauma informed education and support to encourage maintenance of healthy behaviours that impact risk. Note that opportunistic cervical screening/education may be appropriate if a patient requests STI testing.

Eligibility

Patients with a cervix are eligible for cervical cancer screening if they are:

- asymptomatic,

- 25-69 years old (even if they have gone through menopause),

- do not have a history of cervical cancer, and

- have a history of sexual activity (even if not currently sexually active).

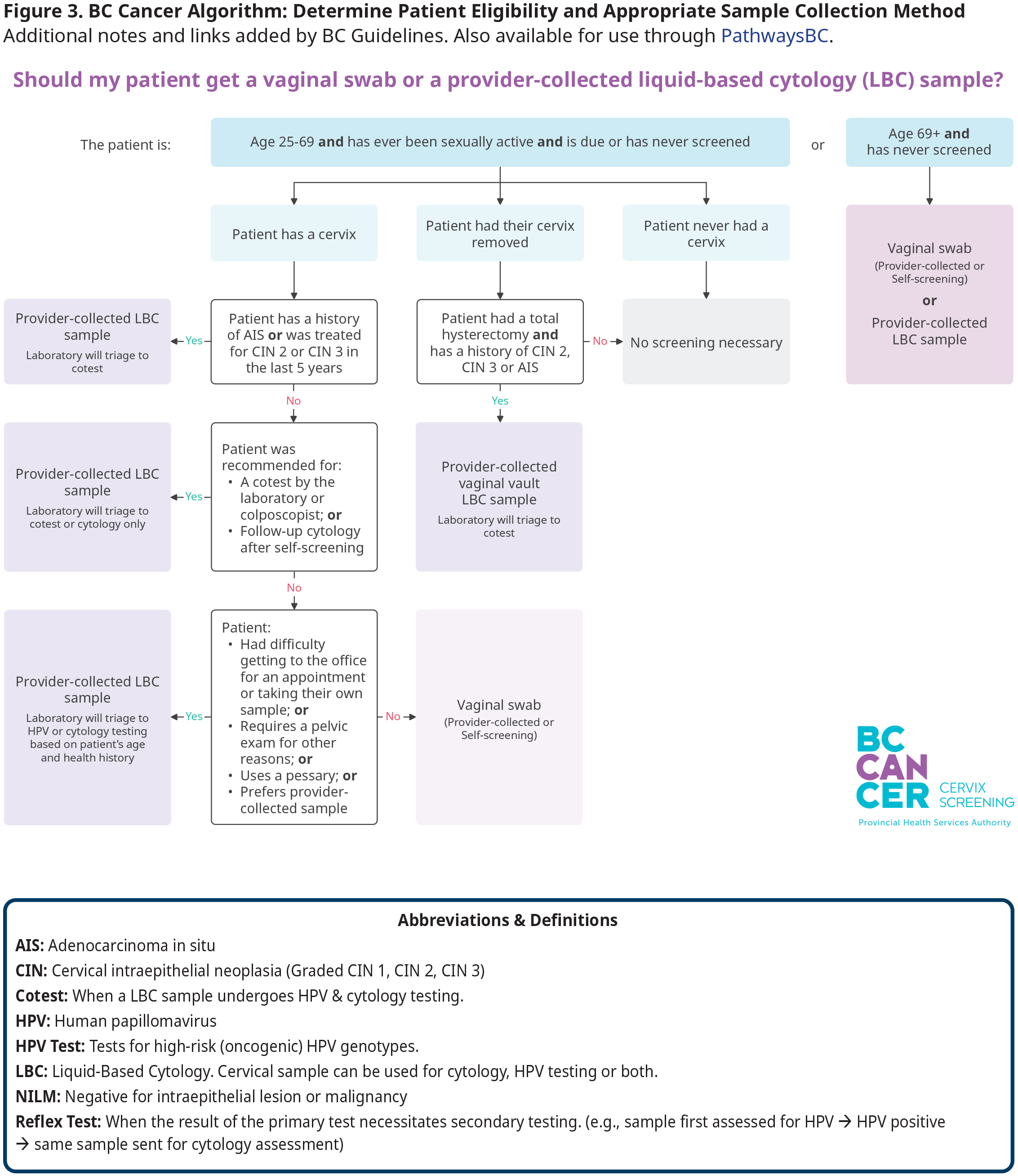

Patients who have had a total hysterectomy only need to be screened if they have a history of CIN 2, CIN3 or AIS. Screening is not recommended for patients <25 years, regardless of history of sexual activity. However, patients >69 years old who have never been screened can still be offered an HPV test. Note that screening in those who are >69 years is indicated if they are immunocompromised or recently discharged from colposcopy and have not had a cervical LBC sample with a negative co-test result in the previous 12 months. Refer to Figure 3: BC Cancer Algorithm: Determining Type of Sample Collection Method for Cervix Screening and the cessation of screening section below for more detail on specific eligibility criteria.

Pregnancy

Screening for cervical cancer is not necessary as a routine part of pre-natal screening and can safely be deferred until after pregnancy for those who are up to date. However, pregnancy may represent an opportunity for those who might not regularly access care or are overdue for screening.

- If screening is to be done during pregnancy, self-screening is not recommended. Instead, the provider should collect a cervical LBC sample or a vaginal HPV swab. Note that the endocervical brush/cytobrush should not be used due to risk of bleeding, which can cause distress for the patient.9

- If screening is deferred to post-partum, patients can do a self-screening sample or providers may collect a vaginal or cervical sample as early as 6 weeks post-partum, provided no vaginal bleeding is still occurring.

Patients Presenting with Symptoms

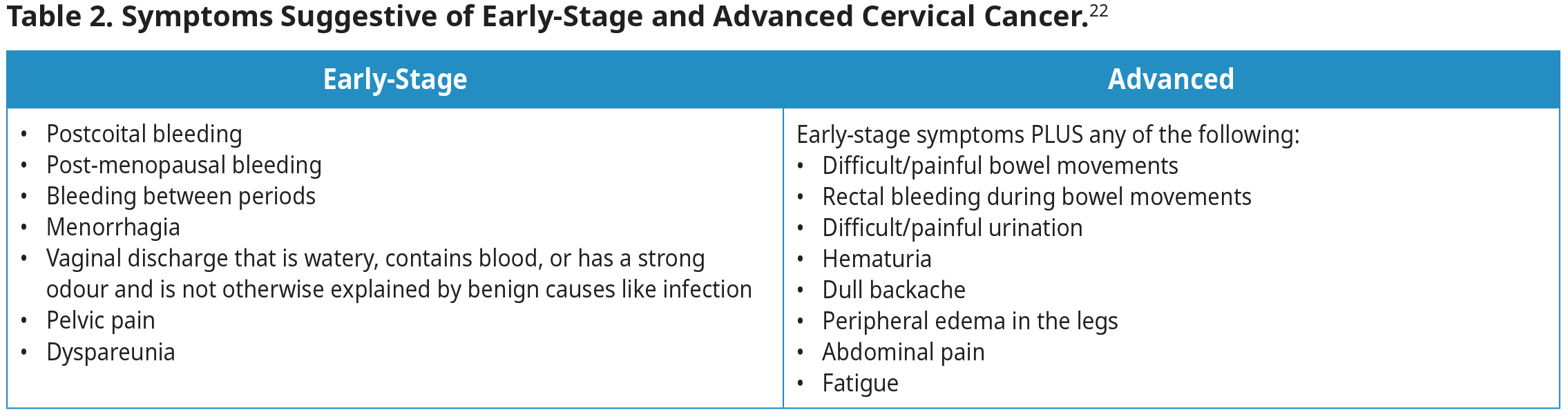

Patients with an HPV infection of the cervix are usually asymptomatic.43 See Table 2: Symptoms Suggestive of Early-Stage and Advanced Cervical Cancer.22 Note that these symptoms are non-specific and may be associated with other causes.

Patients presenting with signs and symptoms should be investigated/managed following best practices, including a speculum examination by someone with experience in gynecologic exams. If any suspicious abnormality is noticed during speculum examination,

- collect a cervical sample for co-test (HPV and cytology testing). It is inappropriate to collect a vaginal HPV sample alone for symptomatic patients; and

- initiate an urgent referral for colposcopic evaluation, without waiting for test results.

Refer to BC Cancer for more detail.

Test Types and Sample Collection Methods

Two test types are used in BC:

- The HPV DNA test detects a high-risk HPV infection using a vaginal or cervical sample.

- The cytology test detects the presence of precancerous lesions using a cervical sample (LBC).

Sample Collection Methods

Evidence indicates that screening of asymptomatic individuals for HPV with a self-collected vaginal sample is as effective as screening undertaken with a provider-collected LBC sample from the cervix.1–5 Several factors influence what collection method is most appropriate for each patient, including patient preference, clinical history, comfort with speculum exam, availability for in person visits, and physical aspects like limited mobility, etc. Refer to Figure 3: Determining Type of Sample Collection Method for Cervix Screening.

-

Vaginal Swab for HPV Testing – Patient or Provider Collected

- Patient Collected (Self Screening): Patients can request a self-screening kit from BC Cancer online or via telephone, even if they do not have a provider. Patients can then collect their own vaginal sample at home using the approved swab and return their completed kit for free via Canada Post. Patients could also choose to collect their sample in their provider’s office.

- Provider Collected: Patients who would like support collecting their vaginal sample may seek assistance from a provider. It is important to note that the HPV swab has a red top with no transport medium to avoid confusing this with a vaginal C & S swab that also has a red top but does have transport medium in the tube. Refer to Appendix B for instructions. Providers can order clinic supplies through BC Cancer here.

-

Cervical LBC Sample for HPV and/or Cytology – Provider Collected Only

- Providers collect cervical samples using a plastic spatula and cytobrush then transfer the sample into a ThinPrep® LBC medium. The lab triages the sample for either HPV testing or cytology based on the patient’s age and any known clinical history.

Screening Results and Follow-Up

Results of screening tests will be provided to the patient and provider. Refer to Figure 2: BC Cancer Cervix Screening Program Algorithm for an overview for average risk patients and page 40-42 of BC Cancer’s Cervix Screening Program Overview for additional detail.

When discussing results with patients, use the terms "HPV detected" (instead of "HPV positive") and "HPV not detected" (instead of "HPV negative"). This terminology better aligns with the natural history of HPV infection and the limitation of testing. For more information see BC Cancer Fact Sheet: Explaining HPV-Detected Results to Patients.

Follow-up differs based on screening method and result. A combination of partial genotyping and cytology on those who test positive for HPV is used to help guide subsequent management through colposcopy (HPV 16 or 18; high-grade cytology) or LBC collection for cytology from primary care provider if only a vaginal swab for HPV was collected.

If colposcopy is indicated, the Cervix Screening Program will automatically refer the patient on behalf of the referring health care provider. Patients will receive a letter advising them that the results of their screening test indicate that further follow-up is needed and that they will be contacted by a colposcopy clinic to arrange an appointment.

A process for unattached patients has been established in BC where the Cervix Screening Program can act as the ordering provider. Patients recommended for follow-up are linked with a clinic in their commu nity to access or support them with recommended follow-up.

Screening Frequency

Screen eligible asymptomatic patients every 3-5 years, regardless of their HPV immunization status. Follow-up frequency/timing depends on previous screening method (i.e., cytology versus HPV) and results. The Cervix Screening Program will advise patient and provider when to screen next.

Cessation of Screening

- Average Risk: Stop screening at age 69, provided that there has been a negative HPV screening test between the ages of 65 and 69 and under no active surveillance of pre-cursor abnormalities.9

- Immunocompromised: Stop screening at age 74, provided there has been a negative HPV screening test between the ages of 65 and 69 and under no active surveillance of precursor abnormalities.9

- Discharged from colposcopy but have not yet completed the post discharge 12-month cervical LBC sample for co-test (HPV and cytology testing) before age 69 (average risk) or 74 (immunocompromised): Continue with screening until they have had a negative co-test. After this, screening can be discontinued.9

Barriers to Participation

Providers should be aware of systemic and personal barriers that can impact patients’ participation in screening programs. Self-screening options serve to reduce some of these barriers and represent an opportunity to increase access to care for patients across BC.44,45

Examples of these barriers include not having a regular care provider, geographical challenges in reaching healthcare or screening services, not being able to access healthcare information or services in a preferred language, racist, sexist, and misogynist policies and practices, as well as the legacy and contemporary negative impacts of colonialism.9,17 Personal factors like being a visible minority, immigrant, low-income individual, underhoused person, transgender, gender diverse, or non-binary individual, having a history of trauma or violence, some religious or cultural beliefs, or previous negative or limited interactions with the healthcare system can also contribute.9,17 Note that these are not exhaustive lists and each patient is unique in their experience of healthcare enablers and barriers.

It is critical that providers apply a culturally safe and trauma-informed approach to build trust and best support all patients, including those who experience specific barriers to screening participation. Refer to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of BC’s Indigenous Cultural Safety, Cultural Humility and Anti-racism practice standard, First Nations Health Authority and Health Standards Organization’s British Columbia (BC) Cultural Safety and Humility Standard and BC Guidelines Extended Learning Document: Primary Care Approaches to Addressing the Impacts of Trauma and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) for more information. Note: Additional training is required before administering the ACEs questionnaire.

Other Clinical / Special Considerations

The benefits of participating in cervical cancer screening outweigh potential harms.5

Note that patients may experience distress or anxiety if a screening HPV test result is positive even though not all infections develop into dysplasia and not all dysplasia develops into cervical cancer. There may also be distress, anxiety, or patient-perceived stigma associated with STIs, disclosure requirements, and impacts on intimate partner relationships.

Self-screening can reduce some barriers and potential harms. However, there are other clinical and special considerations to keep in mind. Previously, screening through provider collected specimens was an opportunity for those who might not otherwise regularly access care to identify/address other health issues. Providers should consider an approach for planned, proactive engagement with their patients to review other care needs including but not limited to recommendations from the BC Lifetime Prevention Schedule, STI screening, sexual health and safety education, access to contraception, etc.

Resources

Abbreviations

| ASCUS | Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance | LBC | Liquid based cytology |

| AIS | Adenocarcinoma in situ | lr-HPV | Low risk HPV |

| CIN | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | NILM | Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy |

| DES | Diethylstilbestrol | Pap | Papanicolaou |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus | TTGD | Two-Spirit, Transgender, Gender-diverse |

| hr-HPV | High risk HPV |

Practitioner Resources

- BC Cancer Screening Program Practitioner Resources

- The lab requisition form for samples collected in a provider office is here.

- Practitioners can order BC Cancer educational materials for their offices.

- Practitioners can order cervix screening supplies here.

- BC HPV Vaccine Program Information (BCCDC):

- BC Lifetime Prevention Schedule (LPS): Looks at clinical prevention services for British Columbians, including screening, behavioral interventions and preventive medications provided by a health-care provider, based on age and sex. The LPS reports show priorities for these services in BC based on each service’s clinical effectiveness, population health impact and cost effectiveness.

- FNHA Health Benefits Program Overview: Outlines six benefit areas: dental, medical supplies and equipment, medical transportation, mental health, pharmacy, and vision.

- RACE (Rapid Access to Consultative Expertise): A phone consultation line for physicians, nurse practitioners and medical residents. Contact your local RACE line for the list of available specialty areas. If your local RACE line does not cover the relevant specialty service or there is no local RACE line in your area, or to access Provincial Services, please contact the Vancouver/Providence RACE line.

- Pathways: An online resource that allows FPs, NPs, and their office staff to quickly access current and accurate referral information, including wait times and areas of expertise, for specialists and specialty clinics. Login required.

- Health Data Coalition: An online, physician-led data sharing platform that can assist you in assessing your own practice in areas such as chronic disease management or medication prescribing. Data can graphically represent patients in your practice with chronic diseases, allowing for reflection on practice and tracking improvements over time.

- Trans Care BC (for Health Professionals): Provides clinical resources and information on supporting trans, Two-Spirt, and non-binary patients.

- PathwaysBC: An online directory of healthcare providers, services, and clinical resources to support clinicians in BC. Requires login.

Patient, Family and Caregiver Resources

- BC Cancer Cervix Screening Program (for Patients): Provides patient education on the importance of cervix screening. Includes program information and handouts for patients.

- HealthLinkBC: Patients can call HealthLinkBC at 8-1-1 toll-free in BC, or for the deaf and the hard of hearing, call 7-1-1. They will be connected to an English-speaking health-service navigator, who can provide health and health-service information and connect patients with a registered dietitian, exercise physiologist, nurse, or pharmacist.

- FNHA Health Benefits Program Overview: Outlines six benefit areas: dental, medical supplies and equipment, medical transportation, mental health, pharmacy, and vision.

- Travel and Accommodations Assistance Program: Available to residents of BC who must travel from their homes to access medical care.

- QuitNow: Provides one-on-one support and valuable resources in multiple languages to help patients plan a smoking cessation strategy. Includes access to a Quit Coach. See: Community and Support | QuitNow. Phone: 1-877-455-2233 (toll-free) Email: quitnow@bc.lung.ca

- Trans CareBC (for Patients): Provides patient information regarding exploring gender affirming transitions, hormone therapy, general health and wellbeing, etc.

ICD-9 Diagnostic Codes

- 180.0 – Malignant neoplasm of endocervix

- 180.1 – Malignant neoplasm of exocervix

- 180.8 – Malignant neoplasm of other specified sites of cervix

- 180.9 – Malignant neoplasm of cervix uteri, unspecified site

- 233.1 – Carcinoma in situ of cervix uteri

- 079.4 – Human papillomavirus in conditions classified elsewhere or unspecified site

- V76.2 – Screening for malignant neoplasms of cervix

Billing Codes

| Description | Fee for Service Model | LFP Model (LFP practitioner/Locum) |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal swab done in office by FP | Visit fee (00100 age series) | Interaction code (98031/98061) |

| Cervical sample for LBC (with speculum) | Visit fee (00100 age series) plus Office Vaginal Speculum exam (14562) plus Mini Tray fee (00044) |

In-person Interaction with a Standard Procedure (98021/98051) |

Appendices

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

References

- Bouvard V, Wentzensen N, Mackie A, et al. The IARC Perspective on Cervical Cancer Screening. The New England Journal of Medicine. Published online 2021.

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; 2014. Accessed November 17, 2023. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/144785

- Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. The Lancet. 2014;383(9916):524-532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7

- Perkins RB, Guido RS, Castle PE, et al. 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors: Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2020;24(2):102-131. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000525

- Arbyn M, Castle PE, Schiffman M, Wentzensen N, Heckman‐Stoddard B, Sahasrabuddhe VV. Meta‐analysis of agreement/concordance statistics in studies comparing self‐ vs clinician‐collected samples for HPV testing in cervical cancer screening. Intl Journal of Cancer. 2022;151(2):308-312. doi:10.1002/ijc.33967

- Delpero E, Selk A. Shifting from cytology to HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in Canada. CMAJ. 2022;194(17):E613-E615. doi:10.1503/cmaj.211568

- Mayrand MH, Hanley J, Franco EL. Human Papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou Screening Tests for Cervical Cancer. n engl j med. Published online 2007.

- Landy R, Pesola F, Castañón A, Sasieni P. Impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality: estimation using stage-specific results from a nested case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(9):1140-1146. doi:10.1038/bjc.2016.290

- Proctor L. BC Cancer Cervix Screening Program: Program Overview.; 2024:1-54. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/Documents/Cervix-Program-Overview.pdf

- BC Cancer Cervix Screening: 2018 Program Results. BC Cancer; 2020:1-28. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/Documents/Cervix-Program-Results-2018.pdf

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of Screening With Primary Cervical HPV Testing vs Cytology Testing on High-grade Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia at 48 Months: The HPV FOCAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(1):43-52. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7464

- HPV Primary Screening: A Resource Guide for Health Care Providers. BC Cancer http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/Documents/HPV-Screening-Resource-Guide.pdf

- Canada PHA of. Human Papillomavirus (HPV). October 12, 2007. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/sexual-health-sexually-transmitted-infections/human-papillomavirus-hpv.html

- Statistics by Cancer Type - Cervix. BC Cancer; 2021:2. Accessed November 15, 2023. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/statistics-and-reports-site/Documents/Cancer_Type_Cervix_2018_20210305.pdf

- Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer. Canadian Cancer Society. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/cervical/risks

- Simkin J, Smith L, Van Niekerk D, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of women with invasive cervical cancer in British Columbia, 2004–2013: a descriptive study. cmajo. 2021;9(2):E424-E432. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200139

- Sacred and Strong: Upholding Our Matriarchal Roles - The Health and Wellness Journeys of BC First Nations Women and Girls. First Nations Health Authority, Office of the Provincial Health Officer; 2021.

- McGahan CE, Linn K, Guno P, et al. Cancer in First Nations people living in British Columbia, Canada: an analysis of incidence and survival from 1993 to 2010. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(10):1105-1116. doi:10.1007/s10552-017-0950-7

- Walboomers JMM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12-19. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F

- Gates A, Pillay J, Reynolds D, et al. Screening for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer: protocol for systematic reviews to inform Canadian recommendations. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):2. doi:10.1186/s13643-020-01538-9

- Burd EM. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(1):1-17. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.1.1-17.2003

- Cervical Cancer Symptoms. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/symptoms

- Khayargoli P, Niyibizi J, Mayrand MH, et al. Human Papillomavirus Transmission and Persistence in Pregnant Women and Neonates. JAMA Pediatrics. 2023;177(7):684-692. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.1283

- Kjaer SK. Type specific persistence of high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) as indicator of high grade cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in young women: population based prospective follow up study. BMJ. 2002;325(7364):572-572. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7364.572

- Kjaer SK, Frederiksen K, Munk C, Iftner T. Long-term Absolute Risk of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grade 3 or Worse Following Human Papillomavirus Infection: Role of Persistence. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(19):1478-1488. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq356

- Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide. Health Canada Accessed November 15, 2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-9-human-papillomavirus-vaccine.html#p4c8a2

- Asthana S, Busa V, Labani S. Oral contraceptives use and risk of cervical cancer—A systematic review & meta-analysis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2020;247:163-175. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.02.014

- Gadducci A, Cosio S, Fruzzetti F. Estro-progestin Contraceptives and Risk of Cervical Cancer: A Debated Issue. Anticancer Res. 2020;40(11):5995-6002. doi:10.21873/anticanres.14620

- Malevolti MC, Lugo A, Scala M, et al. Dose-risk relationships between cigarette smoking and cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. Published online November 10, 2022. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000773

- Muñoz JP, Carrillo-Beltrán D, Aedo-Aguilera V, et al. Tobacco Exposure Enhances Human Papillomavirus 16 Oncogene Expression via EGFR/PI3K/Akt/c-Jun Signaling Pathway in Cervical Cancer Cells. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3022. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.03022

- Palmer T, Wallace L, Pollock KG, et al. Prevalence of cervical disease at age 20 after immunisation with bivalent HPV vaccine at age 12-13 in Scotland: retrospective population study. BMJ. Published online April 3, 2019:l1161. doi:10.1136/bmj.l1161

- St Sauver JL, Finney Rutten LJ, Ebbert JO, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Jacobson RM. Younger age at initiation of the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination series is associated with higher rates of on-time completion. Prev Med. 2016;89:327-333. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.039

- Canada PHA of. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide. July 2024. Accessed March 17, 2025. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-9-human-papillomavirus-vaccine.html

- Summary Basis of Decision for Gardasil 9. Accessed March 17, 2025. https://dhpp.hpfb-dgpsa.ca/review-documents/resource/SBD00222

- An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): Updated Recommendations on Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines. Public Health Agency of Canada; 2024.

- GlaxoSmithKline Inc. Cervarix Product Monograph. Published online May 17, 2024.

- Gardasil 9 Product Monograph. Merck Canada Inc; 2024. https://www.merck.ca/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2021/04/GARDASIL_9-PM_E.pdf

- Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, et al. HPV Vaccination and the Risk of Invasive Cervical Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(14):1340-1348. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917338

- BC Centre for Disease Control. History of Immunization in BC. Communicable Disease Control Manual. Published online November 2023.

- HPV. Immunize BC. June 11, 2024. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://immunizebc.ca/vaccines/HPV

- Lawal S, St-Jean M, Hu Y, et al. Assessing sociodemographic disparities in HPV vaccine uptake among grade 6 and 9 students in the Vancouver Coastal Health region. Vaccine. 2024;42(21):126147. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.07.048

- BC Centre for Disease Control. Childhood Immunization Coverage Dashboard. Accessed January 16, 2025. http://www.bccdc.ca/health-professionals/data-reports/childhood-immunization-coverage-dashboard

- Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection - STI Treatment Guidelines. May 9, 2022. Accessed February 4, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/hpv.htm

- Sultana F, English DR, Simpson JA, et al. Home‐based HPV self‐sampling improves participation by never‐screened and under‐screened women: Results from a large randomized trial (iPap) in Australia. Intl Journal of Cancer. 2016;139(2):281-290. doi:10.1002/ijc.30031

- Ogilvie G, Krajden M, Maginley J, et al. Feasibility of self-collection of specimens for human papillomavirus testing in hard-to-reach women. CMAJ. 2007;177(5):480-483. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070013

|

BC Guidelines are developed for the Medical Services Commission by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, a joint committee of Government and the Doctors of BC. BC Guidelines are adopted under the Medicare Protection Act and, where relevant, the Laboratory Services Act. Disclaimer: This guideline is based on best available scientific evidence and clinical expertise as of the effective date above. It is not intended as a substitute for the clinical or professional judgment of a health care practitioner. |

TOP

TOP