Part 4 - The decision process

After completing this chapter you should be able to:

- describe an approach to decision-making for silvicultural systems

- appreciate the importance of clear objectives for developing silvicultural systems

- differentiate between the various types of resource management

- recognize the potential for stand structural options based on stand data

- appreciate the potential risks that must be considered before choosing a suitable silvicultural system option.

- resource management objectives

- stand structural design (objectives)

- stand structures

- stand structural attributes

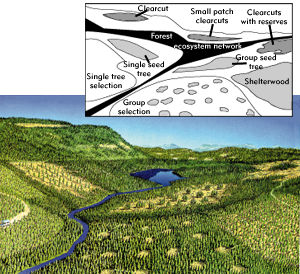

- stand spatial patterns

- successional stage

- stand development

- risk appraisal

Overview of the decision making process

Because designing a silvicultural system is a creative process, the prescriber is constantly revisiting various aspects of the design process in feedback loops which help to tie all components together. However, we will try to present the considerations in a logical sequence.

Quote:

Science is the attempt to make the chaotic diversity of our sense-experience correspond to a logically uniform system of thought

Albert Einstein

Step 1 - Identify resource management objectives

Provincial planning level

Legislation and provincial policies set the stage for management on the ground. Although these provincial documents provide direction, resource management objectives are provided only as general guidelines to the stand level activities.

Regional planning level

Regional land use plans wereestablished by the Lieutenant Governor in Council or three Cabinet ministers. As part of the Commission on Resources and Environment (CORE) process, regional land use plans were developed for four areas in BC: Chilcotin - Cariboo; West Kootenay - Boundary, East Kootenay and Vancouver Island. These plans establish broad resource management zones (RMZs) and objectives. The general resource management zones are enhanced, special, and integrated management zones. Each RMZ may have specific higher level plan objectives.

While regional land use plans provide more specific direction regarding the priorities for resource management and are a necessary starting point where no other higher level plans (HLPs) exist, they may not give specific direction for stand-level management. Higher level plan objectives are intended to capture the social, economic, and environmental goals of an area, while allowing flexibility to on-the-ground activities.

AAC determinations

The allowable annual cut (AAC) determination process uses HLPs where the objectives and strategies impact the determination of AACs. The AAC determinations currently falling into this category are tree farm licence (TFL) management plans and timber supply areas (TSAs). Smaller AAC determinations occur for woodlot licences. The resulting AAC determination by the chief forester specifies harvesting allocations and special considerations in accessing the resources.

Land and resource management plan (LRMP) level

Land and resource management plans (LRMPs) cover areas of the province not addressed in regional strategic plans. Many of the principles are the same: high levels of community involvement, establishment of resource management zones, and establishment of broad resource management objectives. These plans may also be signed off by Cabinet. The LRMP covers a smaller area than a regional plan, and focuses more on district level, environmental, social, and economic objectives.

Landscape unit planning level

Landscape unit (LU) plans, total resource plans, and local resource use plans for watersheds or similar-sized portions of the landscape direct the management at a level between regional/sub-regional and stand. These plans further clarify objectives to maintain biodiversity, identify sensitive visual resource values, set visual quality objectives, manage timber values, and other important resource values. At the landscape level, old-growth management areas may be identified with specific objectives to protect or manage unique or locally significant resource values. Only landscape unit objectives can be established as higher level plans. This level of planning will be important to subsequent stand-level management decisions and the choice of silvicultural system.

Included with the LU process are inventories and management for recreation sites, interpretive forest sites, and recreation trails. As with higher level plans, all of these plans must be consulted. They will likely provide some helpful information when setting objectives, depending on the proximity of the stand and its relationship with the resource feature in question.

If any one of these higher level plans (regional or lower) exists for the area in which you operate, by law you must consult it in setting your stand-level objectives. Depending on the higher level plan you are using, some interpretation may be required. Obviously, the closer to the ground (landscape level or lower), the more clear and specific the objectives will become.

Note: Planning is an evolving process with potentially updated land use plans being available for your area that may guide direction.

Quotes:

Resolving conflicting management objectives at the stand level is extremely difficult and leaves the silviculturist to spread unhappiness about when preparing his stand-level prescriptions.

Gordon Weetman (1996)

Planning is everything...and the plan is nothing.

Napoleon Bonaparte

In British Columbia more than 90 wildlife species, or 16% of the province's vertebrates depend to some extent on wildlife trees for reproduction, feeding or shelter.

Backhouse and Lousier (1991)

Partial cutting accounted for 33% of all harvesting on Crown land in the Kamloops Forest Region during 1996-1997.

BC Ministry of Forests

Step 2 - Landscape level plans under consideration

Landscape level plans will provide context, linking objectives to stand structural objectives/silvicultural systems.

Quotes:

Most silviculturists in British Columbia are faced with the problem of multi-resource forest management and geriatric silviculture. There are virtually no European precedents for this situation.

Gordon Weetman (1996)

You can observe a lot just by watching

Yogi Bera

Step 3 - Collect stand and site data

All decisions on which silvicultural system to choose must be made on a site-specific basis. One option does not fit all! There is often more than one choice that can be used on a site. In these cases, a "best fit" approach, based on the stand structure objectives, will act as a guide for the final decision. Proper collection of stand and site data is key.

Step 4 - List options for stand structural design

Objectives must be tempered with reality. You must know the site and stand features before you can properly identify the range of stand structural options. All of the information normally collected in any pre-harvest prescription process will be helpful. However, if you think that you will be partial cutting, thorough stand information may help clarify the options. Also, enough data to provide a picture of the existing stand will help you justify your prescription to your client, supervisor, or regulatory agency. We can present this type of information in a format called a stand table.

In addition to stand table information, classifying stand structure and pattern gives a more complete picture of the stand. It is also useful to assess the stand's successional stage, which describes the long-term ecological community development. Also, classify the present stand development stage to describe the competition and growth form of individual stems.

Once you have documented existing structural and successional information, think about the silvics of the individual component species and of the interactions between species.

Step 5 - Analyze structural options

Often, with the general resource management objectives in your field notebook, and after a thorough stand examination, including data collection, you feel that several options for stand manipulation seem feasible. Now it is time to thoroughly analyze the ability of each option to be successful. This analysis can be done in three phases:

Review all guidebooks, handbooks, and other valuable references regarding the key stand management objectives. For example, if the critical issues are timber, caribou winter range, and aesthetics, select all key references for caribou and visual landscape management. Consider also the tree species you are managing and more closely investigate its silvics, growth and yield under different light regimes, etc. At this stage it is too early to think about logging logistics, although it may be difficult not to.

Once you have considered all of the nuances of managing for your various objectives, and the ability of the various options to meet those requirements, consider the inherent risks of each option in the setting you are dealing with. At this point, analyze all risks and weigh them against each other. This is the stage where one option may be cast aside because risks are simply unacceptable. Again consult relevant guidebooks, handbooks, and other reference materials.

Choose the options that seem to meet your management objectives, and consider all your operational, logistical, social, risk, and economic issues. You should consider your ability to operationally manage the stand, while conducting logging, site preparation, planting, and stand tending activities. Also, examine the costs associated with those activities.

It makes the most sense to choose the best option to meet your objectives and still have an acceptable risk. Remember to consider the ability of the options to meet your management objectives and the risks involved with each option first, and then consider costs. Also, you may choose a high-risk option, as long as you recognize the risk and have some contingency plans to deal with potential problems.

This analysis phase is often partly done in the field as you get more experienced. You will know most of the questions to ask and you can mull over the issues even while collecting your data. You may emerge from the field with only two options in the back of your brain, each option having several outstanding issues or questions. After consulting references, or even experienced specialists, the choice may become more clear.

Quotes:

We cannot command Nature except by obeying her.

Francis Bacon

Men argue, nature acts.

Voltaire

The most important ingredient in the design of system control is reflection before action.

H. Boothroyd (1978)

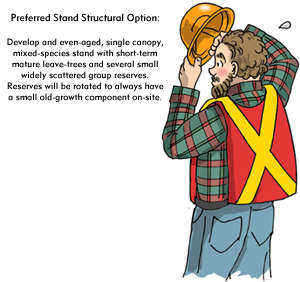

Step 6 - Choose the best options for stand structural design

At this point the best option for stand structural design should be evident from the exercise. The stand structural design should be long term. It should be clear how the stand will change in both the short term (5-25 years) and the long term (25-100 years).

Step 7 - Design silvicultural system

Several silvicultural systems may be capable of matching your stand structural design over the long term. Go back to the biological/ecological questions of species silvics (e.g., shade tolerance levels, regeneration, and growth characteristics) to finalize the system that you think will give you the best chance for predictable yields over the long term and still meet the structural design.

Quotes:

Experience is not what happens to a man. It is what a man does with what happens to him.

Aldous Huxley

Perhaps no silviculturist would admit to prescribing by the book. On the other hand, the public and the media have a strong attachment to these simple prescriptions.

Gordon Baskerville (1992)

Analysis of poor decisions

Use the decision process presented here to analyze some mistakes made when applying silvicultural systems. Try to identify the stage(s) in the process where problems occurred. What were the problems? For example, no system is suitable but an attempt is made to force a system onto a site. Data error caused the wrong system to be chosen.

Self test questions

- Describe conceptually a decision-making process for designing silvicultural systems.

- Describe the four planning levels that provide some direction for resource management objectives. Which levels are most useful to stand-level managers?

- What type of stand data should be collected when developing a prescription for a stand with some complex resource management objectives (which may lead to a decision to use a partial cutting system)?

- Describe briefly the three steps used to analyze your structural options in the office after the field examination.