Capital Asset Management Framework: 8. Capital Procurement

- 8.1 Introduction

- 8.2 Principles

- 8.3 Legal and Ethical Issues

- 8.4 Alternative Capital Procurement

- 8.5 Traditional Capital Procurement

This section may be subject to revision pending the outcomes of the province's Procurement Reform Initiative

8.1 Introduction

After completing the planning process and choosing the best option for meeting service delivery needs, agencies can begin the process of capital procurement. In other words, they can begin to engage the private sector (the market) to acquire capital assets and related services, bearing in mind the Province’s commitments to value for money and protecting the public interest.

The following chapter details:

- principles guiding capital related procurement

- key legal and ethical considerations

- the alternative capital procurement process, and

- the traditional, publicly-financed capital procurement process

Tools are also provided, at the end of relevant sections, to support the alternative and traditional procurement processes.

8.2 Principles

The following principles guide all public sector capital procurement:

Allocation and Management of Risk

Procurement processes must be fair, open and transparent to assure the public and potential partners of the integrity of the process and the desired outcome.

The public must be given every opportunity to participate in government business. Required qualifications for bidders (e.g. financial capacity and technical capability) should be proportionate to project size and complexity.

Allocation and Management of Risk

Procurement strategies should allocate risks to the party (e.g. agency, supplier, contractor) best able to manage them.

Experience, knowledge and training of procurement staff should be commensurate with the nature and complexity of the purchase.

Competition

Capital procurement opportunities must be tendered publicly, using competitive processes. Reasonable exceptions may be made in unusual circumstances (e.g. in matters of urgent public health or safety, or where there is only one supplier of goods or services).

Value for Money and Protecting the Public Interest

Procurement decisions must be based on value for money assessments with due regard for protecting the public interest.

The cost of procurement should be appropriate to the value of the goods or services being acquired, and the risks associated with the procurement.

8.3.1 Legal Considerations

Public sector procurement must take place in full accordance with the law, including inter-governmental agreements such as the Agreement on Internal Trade. Agencies should ensure that procurement personnel are knowledgeable in the applicable legal areas.

8.3.2 Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act

The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) governs disclosure of information in the custody or control of public agencies. Agencies to which the Act applies can obliged to release procurement information unless the information is excepted from disclosure by the legislation. Such exceptions include disclosures that would be harmful to business interests of a third party or the financial or economic interest of a public body

Agencies should contact their designated FIPPA contact for specific advice prior to disclosing any procurement information, other than that which is part of the public tendering process.

8.3.3 Intellectual Property

Intellectual property includes property protected by patent, trademark, industrial design or copyright.

To ensure the proper protection of intellectual property, agencies engaged in capital procurement should ensure that their solicitation documents specifically address how intellectual property issues should be handled. Agencies should consult with their legal advisors on addressing intellectual property issues.

Typically, solicitation documents include a statement detailing how the agency will treat intellectual property. For example, solicitation documents should include a statement indicating that all documents, including proposals submitted to the Province, become property of the Province.

8.3.4 Lobbying

Lobbying generally refers to activities intended to influence government decision- making. Specifically, it involves communication with public office holders – as defined in the Lobbyist Registration Act – by parties external to government.

Lobbying should not be permitted during procurement because it can undermine the integrity of the process and potentially compromise the public interest. To ensure that procurement processes are, and are seen to be fair, transparent and open, agencies should:

- designate a key contact person to respond to any inquiries about the procurement process

- inform bidders that inquiries about the process must be directed in writing to the key contact person

- ensure that such enquiries are recorded and distributed to all project proponents with the agency’s response, with appropriate exceptions for proprietary information, and

- adopt “no-lobbying” policies prohibiting bidders from communicating with any representative of the agency or Province after the procurement process starts – except in the case of routine inquiries, as described above. Bidders should also be prohibited from discussing the project with the public or the media, other than as expressly directed or permitted by the Province

8.3.5 Conflict of Interest

In the context of capital procurement, a conflict of interest (real or perceived) occurs when a member of, or adviser to, a procurement team has a relationship or interest that might be seen to prejudice their impartiality. For example, an agency employee or advisor could have a family member in private business, or be involved with a proponent, who could potentially benefit from a procurement decision.

Conflicts of interest, both real and perceived, are not uncommon and can often be managed effectively. The key is to identify them early in the procurement process, and to take appropriate steps to address and effectively mitigate them in a timely way.

Agencies should develop processes (as part of the solicitation process) to ensure that all procurement team members and their advisors:

- declare and address any real or perceived conflicts of interest before the bidding process begins, and

- identify and address any new or changing conflicts (real or perceived) that arise during the procurement process

Agencies should also develop processes to address the following related issues:

Unfair advantage: This may arise where a contractor entering a competition has had:

- the opportunity to structure the competition in a way that favours him/herself (e.g. by designing an evaluation process that prefers his/her specific skills), or

- access to information giving her/him an advantage over other proponents

Often, this issue is addressed by fully disclosing the advantage so that other bidders will be aware of the circumstances under which they enter the competition.

Confidential information: This issue is similar to unfair advantage. It occurs where one party has access to information that is not available to other bidders. When this happens, agencies should ensure that there is some means of addressing fairness in the process.

8.4 Alternative Capital Procurement

8.4.1 Introduction

As discussed in Chapter 4, alternative capital procurement generally refers to any method other than traditional buy-and-borrow or design-bid-build procurement. The process can be broken into three basic stages:

- Solicitation: which includes preparing and issuing documents such as Requests for Expressions of Interest (REOIs), Requests for Qualifications (RFQs), and Requests for Proposals (RFPs)

- Evaluation/Negotiation: the evaluation of qualified proponents and their proposals against measurable, clearly defined benchmarks and subsequent negotiation with the preferred proponent; and

- Contract Award: the process of awarding the contract to the successful bidder

Once the award is made, the focus shifts to managing the contract and, later, monitoring performance of the asset and/or service.

8.4.2 Solicitation

Solicitation begins with the preparation of necessary documents and concludes with the receipt of proposals from bidders. It may follow a one-step or a two-step process, depending on the project’s nature and complexity.

A one-step process typically involves issuing a Request for Qualification (RFQ) or a Request for Proposals (RFP). This is appropriate where the partnership potential is clear, project requirements are well defined, and only a limited number of firms could reasonably be expected to be interested in the project.

A two-step process is often preferred for more complex projects. It involves issuing a Request for Expressions of Interest (RFEOI) to short-list qualified potential bidders, followed by an RFP for detailed

proposals. This approach acknowledges the cost of preparing and evaluating RFP responses, and can improve efficiency.

In some cases, agencies may wish to meet with several potential bidders before issuing solicitation documents to determine the level of interest, experience and expertise available in the marketplace. This “market sounding” can inform the solicitation process and is appropriate in cases where:

- there is uncertainty regarding market capacity (e.g. whether adequate interest or technical capacity to ensure a competitive process), and/or

- advice is required on certain aspects (e.g. terms) of solicitation documents under development to ensure they are feasible or understandable

Agencies using market sounding should ensure that the process does not create, or appear to create, an advantage to any potential bidder(s). For further guidance, see Section 8.4.5, Conflict of Interest.

8.4.2.1 Request for Qualifications (RFQ) or Request for Expressions of Interest (RFEOI)

RFQs and RFEOIs are used to short-list qualified proponents and assess their qualifications, including their project team, financial resources and track record for controlling, managing and delivering specific projects and/or services.

While RFQ processes can be used to select a potential partner with whom to enter contract negotiations, RFEOIs are typically used as

the first part of a two stage process to solicit ideas for further development at the RFP stage. Once an RFQ or RFEOI closes, responses must be evaluated by a selection committee according to the criteria established in the solicitation documentation. In instances where a two-step process is being employed, an RFP may then be used to select a successful bidder.

At a minimum, an RFQ or an RFEOI should generally include:

Procedural information

- details about the selection process (e.g. one-step or two-step process) and the schedule for selection

- submission procedures including the documentation required and administrative matters such as the name of the agency contact person and details regarding bidders’ meetings, questions and submission requirements

- an outline of the evaluation process including the criteria used and their relative weighting, and

- general guidelines in areas such as conflict of interest, rights of the Province and required financial deposits. This should include a "no-lobby" provision instructing bidders (including any third-party representatives) not to communicate with any representative of the agency or Province after procurement begins

Project & proponent information

- where applicable, a description of physical aspects such as service delivery outputs, design guidelines, environmental considerations, operation and maintenance requirements and property acquisition details

- a section requiring proponents to describe, in general terms, their approach, ideas or innovation for addressing the performance outcomes and/or outputs

- a section requiring proponents to provide qualifications, past experience and financial and other capacity information, and

- specific role(s) and risks that successful proponents are expected to undertake (e.g., finance, design, construction, maintenance)

Technical and legal information

- details of any specific legal or provincial provisions that apply to the project

- definitions of terminology used in the document, and

- any particular policy regarding the payment of honoraria to proponents

8.4.2.2 The Request for Proposals (RFP)

The purpose of an RFP is to solicit enough information from private sector proponents to assess the relative merits of proponents’ proposals. Where applicable, agencies should consult with their line ministries to develop RFP documents. These documents should generally include, at a minimum:

Procedural information

- an introduction specifying the objectives of government’s RFP process and defining important terms

- instruction on preparing the proposal, important deadlines, contact information and procedures for inquiries

- guidelines regarding conflict of interest and a "no-lobby" provision (as described in Section 8.4.4)

- evaluation criteria, their relative weighting and the process for applying them to proposals, and

- a clause advising that a meeting will be held to de-brief project proponents subsequent to evaluation

Project information and proposal requirements

- clearly defined and measurable output and/or outcome specifications (mandatory and desirable program and/or asset performance requirements). These are specifications suitable for payment on a services-delivered basis are most effective

- requirements for disclosing and presenting project costs (e.g. capital, operating and maintenance costs), revenues, balances, and provincial contributions

- details about the Public Sector Comparator (i.e. raw PSC and competitive neutrality information) to enable bidders to demonstrate the relative benefits of their proposals

- requirements for detailing the proposed allocation of project risks (however, solicitation documents should not include government's estimates of the value of the risk transfer);

- requirements for presenting project finance details; where applicable, market assumptions to be used by all proponents should be specified (e.g. benchmark interest rates for financing)

- indemnification and insurance requirements

- provisions to safeguard the public interest

- relevant documentation related to the proposal’s financial terms and conditions including, if available, draft lease and purchase agreements, and

- wherever possible, an opinion from the agency’s auditor regarding the accounting treatment of the proposed transaction (i.e. project financing structure)

Technical and legal information

- general requirements for the conduct of the RFP including the agency’s right to amend proposals

- an indication that the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act applies to the RFP process

- a statement indicating that all documents, including proposals submitted to the Province, become property of the Province

- a clause reserving the agency’s right to reject any or all proposals and to cancel the RFP

8.4.2.3 Evaluation Criteria

As identified above in Section 8.4.2.2., evaluation criteria must be clearly defined in the RFP, and must allow for accurate assessments of:

- value for money compared to the Public Sector Comparator (PSC). Alternative procurement proposals must clearly demonstrate a benefit over the PSC that includes an assessment of the risk transfer

- other value for money costs and benefits not included in the PSC (quantitative or qualitative), and

- each proposal’s capacity to protect the public interest

Typically these criteria have been identified and refined throughout the planning process (i.e. in the business case and any refinements thereafter based on market sounding, if applicable).

8.4.2.4 Approval Requirements

Depending on the nature of the project (e.g. scope, cost, complexity, public policy issues) agencies may be required to seek Treasury Board approval prior to issuing (tendering) the RFEOI or RFP.

8.4.3 Evaluation & Negotiation

This phase of the alternative procurement process includes the evaluation of proposal documents - according to criteria disclosed in the RFP - and the final negotiation of a contract with a preferred proponent.

In evaluating proposals, agencies must pay attention to fairness and consistency. They must also ensure that the deliberations leading to any decisions are well documented. During this stage, communications with proponents must be consistent with the process identified in the solicitation documents.

Typically, a preferred proponent is identified through the evaluation process and negotiations are initiated. Before commencing negotiations, agencies should consider the following issues:

identification of a clear negotiation process or framework. For example, the agency should work with the preferred bidder to identify, define and prioritize the issues that require negotiation; establish the contract drafting process; and agree on a dispute resolution process

- identification of personnel who have the necessary skills and experience (e.g. negotiating, legal, financial, etc.) to undertake the negotiations, as well as clear direction as to their mandate and decision-making authority (e.g. limitations)

- parameters in which the agency has the authority to negotiate (e.g. financial, potential term of the contract, policy parameters), and

- time frame for negotiations (e.g. consideration of when service is required to be operational)

In some cases, agencies may also require Treasury Board approval prior to negotiating a contract with the preferred bidder, depending on:

- the project’s risk profile and the extent of prior approvals

- related public interest issues, and

- the agency's management track-record

Such approval may be required to receive final directions and decisions on the negotiating parameters.

8.4.4 Contract Award

In some circumstances (e.g. where the final contract negotiated materially deviates from the approved project parameters) agencies may require Treasury Board approval prior to contract award.

Once approval is secured and a contract is executed, a public announcement should be made, consistent with the communications policy and plan for the agency or project. (For guidance, see Chapter 6, Public Communications.)

Agencies should also meet with unsuccessful proponents to brief them on the outcome of the procurement process.

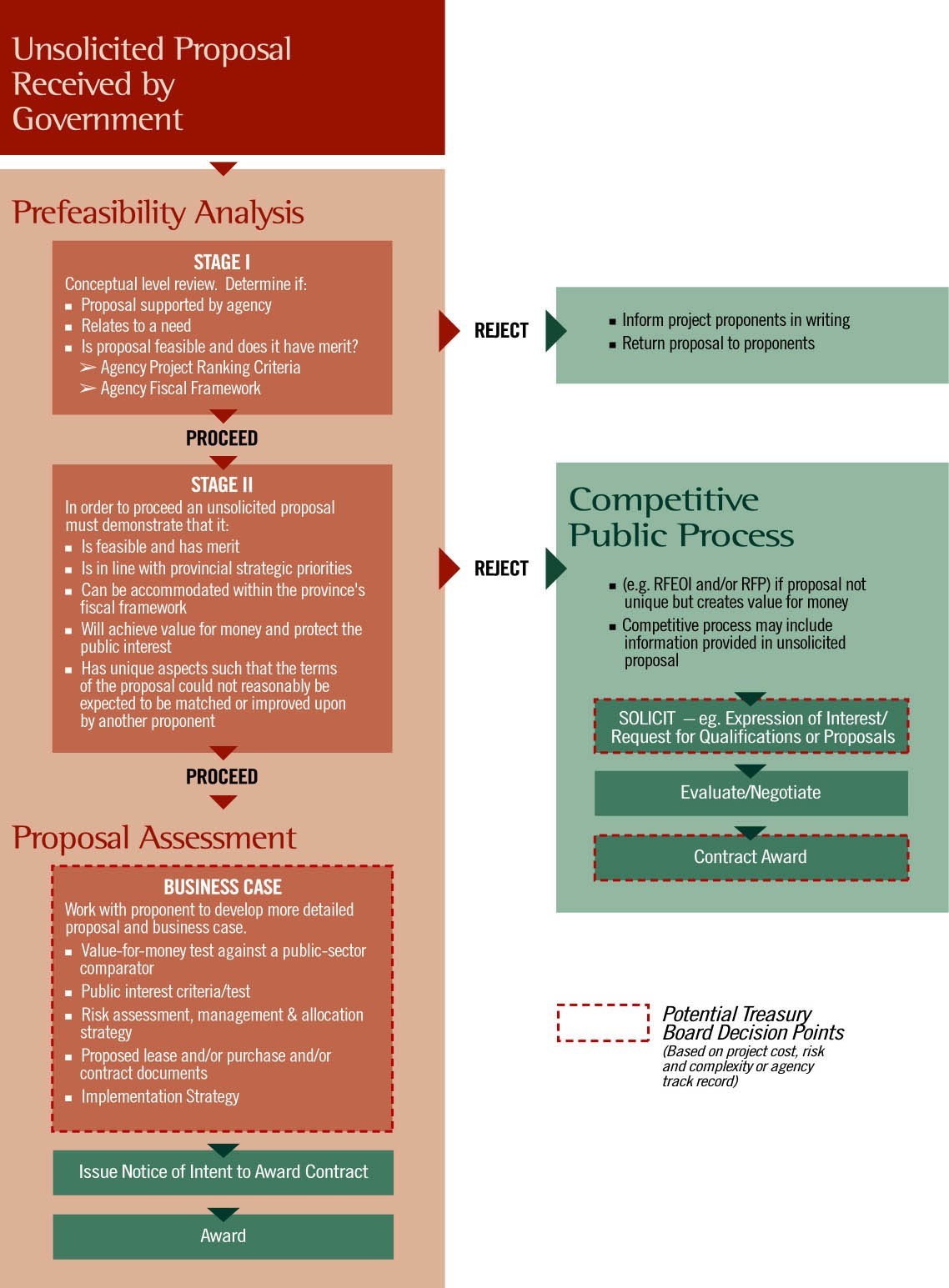

8.4.5 Unsolicited Proposals

Agencies may occasionally receive unsolicited proposals from the private sector, offering a unique business relationship related to a specific project or service. This can pose a procedural challenge because – on the one hand, the Province is committed to ensuring that public procurement processes are open, fair and competitive. On the other hand, it is also committed to finding the best solutions that offer value for money and protect the public interest – which, by necessity, involves considering the widest possible range of potentially feasible options.

The province’s process for handling unsolicited proposals enables it to proceed where it can be demonstrated that:

- the proposal results in value for money (e.g. relative to a PSC) and protects the public interest, and

- the level of value for money achieved could not reasonably be expected to be matched or exceeded by another proponent

Agencies should first review unsolicited proposals at a conceptual level to determine if they have any merit. If not, they should be returned to the proponent.

Unsolicited proposals deemed to have merit may be “sponsored” by an agency and, where applicable, the ministry responsible.

A two stage process should then be followed, including:

- pre-feasibility analysis, and

- proposal assessment

Figure 8.4.6. below summarizes the process for managing unsolicited proposals.

8.4.5.1 Pre-feasibility Analysis

The sponsoring agency and, where applicable, the responsible ministry use a two-stage process to conduct a pre-feasibility analysis of an unsolicited proposal.

Stage One examines:

- whether the proposal has the support of both the agency responsible and the ministry responsible (if applicable)

- if the proposal relates to a need supported by the ministry (if applicable), and

- whether the proposal appears to be feasible and has merit

Agencies must reject proposals that do not meet these criteria, and provide an explanation in writing to the project proponents. Proposals that do meet the stage-one criteria may proceed to stage two.

Stage Two of the pre-feasibility analysis examines:

- whether the proposal will provide value for money, and

- whether it has unique aspects, providing a level of value for money that no other proponent could reasonably be expected to match or exceed. This may happen, for example, where a proponent owns the only viable project site

When the stage-two criteria are met, the agency may work with the proponent to develop a more detailed proposal and/or business case.

Proposals which are not deemed to be unique may be subject to a competitive proponent-selection process.

Before negotiating contract terms, the agency must issue a public Notice of Intent to award a contract. The purpose of the Notice of Intent is to validate the conclusion that no other proponent can reasonably be expected to meet or exceed the terms of the proposed contract.

8.4.5.2 Proposal Assessment

Unsolicited proposals that pass the pre-feasibility analysis are assessed on the same basis as proposals received through a competitive solicitation process. They must undergo complete value-for-money and risk assessments, using an appropriate Public Sector Comparator where applicable. They must also be assessed for their capacity to protect the public interest.

8.4.6 Contract Management and Performance Monitoring

Once a contract is signed, the agency’s role shifts. The focus now is on making sure that both the agency and the private partner fulfil their obligations under the contract. To this end, agencies should ensure their managing staff:

- have the appropriate contract management expertise and the requisite delegations of responsibility and accountability

- carry out regular, detailed reviews to ensure that the project remains on track and performance targets are met. This includes monitoring the contractor’s performance against pre-determined measures (e.g. quality, quantity) and ensuring that progress billings (if any) bear a proper relationship to the work performed to date

- identify the cost and time impacts of possible contract amendments necessitated by any unexpected findings

- maintain open and professional lines of communication with the contractor’s authorized representatives

- ensure public reporting requirements are met

- ensure that all financial guarantees and insurance coverage remain in place during the contract term, and

- take appropriate and timely corrective action where necessary

8.5 Traditional Capital Procurement

One of the key objectives of the Capital Asset Management Framework is to support public-sector agencies to innovate and find the most efficient ways to meet capital-related needs. In all cases, agencies are encouraged to consider the widest possible range of options, and to choose the one that:

- best meets service needs

- delivers the best value for money, and

- best protects the public interest

Traditional, publicly-financed procurement is appropriate when it meets these tests. It may be used as a stand-alone strategy, or as part of an integrated strategy in combination with alternative service delivery or alternative procurement approaches.

The following section offers guidance on traditional procurement, including:

- the contracting methods preferred by the Province and some of their characteristics (e.g. risks and benefits)

- other methods that can be useful in certain situations but involve greater potential risk to the agency

- the typical steps involved in a design-bid-build procurement

- process, and

- critical tasks that should be addressed at each step

8.5.1 Preferred Contract Methods

8.5.1.1 Design-Bid-Build (Stipulated Sum Contract)

Stipulated sum is a standard contract pricing method used in the building industry. It is also the Province’s preferred approach for traditional capital asset procurement. With this method, a fully- designed project is tendered with working drawings and a set of contract terms that will apply to the successful bidder.

Contractors bid on the project, quoting a fixed or stipulated sum to complete the work, and the contract is awarded to the lowest qualified bidder. This method is preferred because it provides relative certainty regarding final project costs and the sharing of risks.

Typically, the price payable by the agency is fixed, regardless of the contractor’s actual costs to complete the work, while any changes initiated by the agency are paid as “an extra" or "change order" at a negotiated price. Progress payments are made at pre- determined milestones or as specified proportions of the work are completed.

8.5.1.2 Unit Price Contracts

Unit price contracts are useful in cases such as engineering projects where site conditions may be variable (e.g. roads, bridges, sewer lines and water lines). Work is divided into a series of units, each with a description and an estimated quantity. Contractors quote unit rates for each work category and multiply the rates by the estimated quantities to estimate a price for each item. The final cost of the contract is determined by multiplying the actual quantities by the appropriate unit rates.

Generally, the unit price payable by the agency remains fixed, regardless of the contractor’s costs to complete each unit of work. Progress payments are based on the actual units of each item of work performed by the contractor and accepted by the agency. This pricing method is appropriate when neither party can control the quantity of work required to perform each project task.

8.5.2 Contract Methods For Specific Circumstances

In specific circumstances – as identified in agencies’ business cases – contract methods other than stipulated sum or unit price may be more appropriate and achieve better results.

However, these methods can also involve a greater degree of risk. They require careful consideration and administration.

8.5.2.1 Construction Management

Agencies using construction management (CM) contract with a firm to manage a project’s tendering and construction. A CM firm may also be contracted earlier in the process to advise the agency on construction-related design issues, or the construction process and cost.

Unlike the traditional design-bid-build approach, CM eliminates the role of a prime contractor. The agency contracts directly with trades, suppliers and the other contractors involved in the project. The CM firm acts as the agency’s agent, managing the contracts and the construction process.

In some cases, CM is used to “fast-track” a project. In fast-tracking, the agency hires a construction manager to work with the design team, and early phases of construction (e.g. site preparation or foundations) are tendered while the later phases are still being designed.

Fast-tracking and other forms of CM may be appropriate where:

- project components must be tendered in sequence to manage potentially critical service or facility disruptions during construction

- a project’s delivery schedule must be accelerated to meet critical service or operational requirements, or

- the agency can demonstrate that there may be insufficient industry capacity to ensure competitive bids from general contractors, due to a project’s location

Because of their direct relationship with trades, suppliers and other contractors, agencies using CM assume most of the risks generally assigned to the prime contractor under a stipulated sum contract. This includes the risk of cost overrun. Agencies choosing CM are solely responsible for funding any costs above the approved project budget.

Construction managers, trades and all other suppliers should be selected through competitive public processes, and contract documents should be consistent with industry standards. The contract between the agency and the construction manager should include specific performance requirements for project schedule, scope, budget and construction quality, to help protect the agency from unnecessary risk and liability.

8.5.2.2 Design Build

Agencies using this approach contract with a private partner to both design and build a facility to meet the agency’s standards and performance specifications. The agency owns and, in most cases, operates the completed facility. Payment is generally at major project milestones.

The design-build approach can provide design, cost and schedule benefits by allowing greater freedom for private sector innovation. By integrating design and construction, this procurement method can also sometimes facilitate faster delivery. It is appropriate in cases where an agency can clearly articulate its performance requirements and is seeking innovative approaches or solutions.

The primary risk of this approach is that the private partner has no vested interest in the facility’s long-term performance. Its responsibility expires with the warranty period. Increasing the level of detail in contract specifications may help reduce this risk. However, it can also dilute the method’s potential benefits.

8.5.2.3 Cost Plus Contracts

Under a cost-plus contract, agencies agree to pay the contractor’s actual costs to carry out the project, plus a fixed percentage for overhead and profit. Progress payments are based on the quantity of resources consumed in a given time period. The agency bears all risks associated with project costs.

Because of its high level of risk to the Province, this approach is only appropriate in highly-specialized circumstances. For example emergencies related to public health or safety, or when the agency has the ability to carefully control the inputs (e.g. material, labour) needed to complete each task.

8.5.3 Traditional Capital Procurement Process Design-Bid-Build

Agencies pursuing traditional procurement may choose from a range of contracting methods, depending on their specific needs. In most cases, though, the Province’s preferred method, design-bid-build, will be the most effective. Therefore, it is described in detail throughout the remainder of this chapter.

8.5.3.1 Design Phase

The design phase beings with the selection of a consultant and includes the range of activities leading to a public tender. As in other aspects of capital asset management, decisions in this phase should focus first on service needs and agencies should strive to ensure that needs are met effectively at the lowest possible life-cycle cost.

8.5.3.1.1 Consultant Selection

Agencies planning capital expenditures typically hire consultants (e.g. architects and engineers) to determine specifications, design facilities, prepare contract documents, evaluate tenders and administer contracts. Qualified consultants should be chosen through a fair, open and transparent competitive process. Selection criteria should include, at a minimum:

- technical and financial capacity to complete the work

- relevant experience

- fees, and

- where appropriate, confirmation of professional liability insurance

In a design-bid-build, "design" typically refers to the planning, design and engineering of a new capital asset, or modifications to an existing asset. Although the design process varies by sector and engineering discipline (e.g. civil or structural) it is usually divided into a series of stages or phases. For example, road design is usually phased as design/engineering/construction, while building design, as a rule, has the following three phases:

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| Schematic Design | Conceptual or preliminary-stage design, concerned with aspects of the site and the relationships among building elements and physical adjacencies of space, height, massing and alternative design ideas. Can inform quite detailed cost estimates (± 10%-20%). |

| Design Development | More specific design with detailed architectural solutions and the development and integration of engineering (structural, mechanical, electrical) systems. More accurate cost estimates are possible. Typically approximately 4% of the project budget may be spent to complete the design development phase. |

| Working Drawings (Contract Documents) | Consist of complete (i.e. tender ready) working drawings and detailed technical specifications. Accurate cost estimates are available at this stage. As a rule of thumb, an additional 1½% of the project budget may be spent to complete working drawings. |

The challenge at this stage is to design a project that meets functional specifications and achieves value for money (e.g. least life-cycle cost) within the available budget.

Agencies are more likely to meet this challenge successfully when they have:

- prepared complete functional programs

- developed accurate budgets and project scopes through business case analysis

- established clear design standards, and

- implemented effective cost management processes

Chapter 9 (Budget and Cost Management) provides additional detail in these areas.

8.5.3.1.1 Preparing Contract Documents

The design process usually concludes with the preparation of contract documents, which are commonly considered in two parts:

Front-end documents detail the basis on which the agency will hire a contractor. Typically prepared by the prime consultant, these documents generally include seven sections:

- Notice to contractor

- Specification index

- Instruction to bidders

- Tender form

- General conditions

- Supplementary general conditions

- Addenda

Several industry-standard front-end documents are available for use by public-sector agencies. The Province supports the use of the following:

- CCDC-2 2008: this is the industry standard stipulated sum contract, developed by the Canadian Construction Document Committee (CCDC)

- Master Municipal Contract Documents (MMCD): this set of front-end documents was developed by the MMCD Association for use on municipal construction contracts with a focus on civil engineering projects

These standard documents do not necessarily fully reflect public- sector risk allocation strategies and business practices. Therefore, agencies should consider using supplementary conditions in their contracts to address issues unique to their area of business, or to a specific project.

Where applicable, agencies should also contact the Risk Management Branch, Ministry of Finance, to ensure contract documents include government's standard indemnity, insurance or other risk management related clauses appropriate to the program area.

Agencies may also want to use the Procedures and Guidelines Recommended For Use on Publicly Funded Construction Projects. These guidelines were prepared by the Public Construction Council of British Columbia.

Back-end documents include the project’s working drawings and specifications. These should be completed in detail prior to tender. Incomplete or poor-quality drawings pose a risk to both the agency and the contractor. They can lead to change orders and extras during construction, adding to the project’s cost and complexity.

8.5.3.2 Tender (Bid) Phase

The tender phase of a project commences with bid notification and ends with tender closing. Agencies should ensure that tendering processes comply with both public policy objectives and the body of tendering-related case law.

Government is committed to open procurement to allow fair competition and provide value for money.

The Agreement on Internal Trade (AIT) sets out the rules for the competitive tendering of contracts to provide goods, services and construction. For construction, the AIT applies as follows:

- for ministries, where the procurement value is $100,000 or greater

- for local agencies, where the procurement value is $250,000 or greater, and

- for Crown corporations, where the procurement value is $5 million or greater

Below these thresholds, agencies are encouraged to openly and fairly tender work using a method of solicitation appropriate to the value of the construction, goods or services being acquired.

Own forces refers to the in-house trade and technical staff often retained by local agencies, typically defined as employees by the Employment Standards Act. While it is the Province’s objective that as much capital-related work as practical be tendered publicly through open and competitive processes, some collective agreements contain “own forces” provisions. These provisions enable in-house staff to complete work, or divisions of work, within specified thresholds.

Bid notification is the process of alerting potential bidders to contract opportunities and inviting their bids through an Invitation to Tender. Where the Agreement on Internal Trade (AIT) applies (see Section 8.5.3.2.1) potential contractors must be notified of all construction contracts through a nationally accepted bulletin board and/or a pre-qualified bidders’ list. Pursuant to government policy in support of open, fair and competitive tendering, agencies should also consider posting bid notifications in recognized trade publications and newspapers to ensure broad industry and regional exposure, and to post notifications for projects below AIT thresholds.

8.5.3.2.4 Contractor Pre-qualification

In a traditional procurement process, contractors are generally considered to be qualified based on two criteria:

- their ability to reliably perform the work, and

- their ability to secure the necessary bonds

In many cases, these criteria are sufficient. However, there may be situations where agencies feel the best value for money can be achieved by employing a process to prequalify contractors. For example, agencies may require specific expertise for a particular project (e.g. one that uses highly-specialized construction techniques or must be delivered without service disruptions).

In such circumstances, agencies may use pre-qualification criteria to develop a bidders’ list, a list of contractors the agency has screened in advance and identified as potentially qualified to perform the work required.

Pre-qualification criteria should be objective and must be specifically identified prior to bid notification.

8.5.3.2.5 Security Requirements (e.g. Bonding)

Bid Security

Each tender form submitted by a contractor must be accompanied by a bid bond equivalent, typically in the amount of 10% of the total tender amount. These bonds should be retained by the agency until it receives contract security.

Certified cheques and guaranteed letters of credit should only be accepted in exceptional circumstances.

Bid bonds from unsuccessful bidders should be returned promptly after a contract is signed.

Contract Security

To ensure they have sufficient contract security, agencies should generally require bidders to provide performance bonds, and labour and materials payment bonds within a specified period (e.g. 14 days) from the date of contract award. Typically, each of these bonds is equivalent to 50% of the contract price.

8.5.3.2.6 Use of Separate and Alternate Prices

In their contract documents, agencies may identify specific items (e.g. building envelope material, parking lots, landscaping) and request separate or alternate prices for those items. This approach can provide increased budget and design flexibility. However, it must be managed carefully to ensure that selection processes are, and are seen to be, fair and transparent.

Separate and alternate prices should be treated as deductions from, or additions to, the base tender price. In evaluating bids, the base tender price should prevail (i.e. over a comparison of prices that include additions or deletions related to separate or alternate prices).

8.5.3.2.7 Use of Bid Depository

The bid depository is a system for administering the tender process between trade and general contractors, facilitating the receipt of sealed bids. Operated by the B.C. Construction Association, the B.C. bid-depository system is designed to:

- enable general contractors to receive trade bids in writing, in adequate time before a general tender close, to promote fairness, equity and quality in the bidding process among trade contractors, and

- protect subcontractors from bid shopping; the practice of soliciting a bid from one subcontractor and then disclosing it to competitors in an attempt by the prime to get a better price

Bid depository rules require prime contractors submitting tenders to agencies to use only subcontractors who have submitted valid prices through the bid depository.

Agencies may choose to require the use of the bid depository system for general contracts. Often, this approach is used when divisions of work are expected to exceed $100,000. However, agencies may choose to use the bid depository for divisions of work below this threshold.

8.5.3.2.8 Scheduling Bid Closing

Agencies issuing tenders should allow adequate time (e.g. 15 days) for bids to be prepared. If additional time is needed, bidders should be notified at least three days before the tender closes, through an addendum to the initial tender documents.

8.5.3.3 Tender Opening and Award

This phase of capital asset management follows a formal process that should conform to established industry procedures, and must be well documented. The process outlined below identifies key tasks and typical processes that should be followed in a tender opening, concluding with contract award. This section provides guidance on some of the terms (i.e. what should be addressed) in front-end documents. However, the specific requirements of individual projects must also be considered.

Tender opening should be attended by one or more of the agency’s representatives (e.g. the prime consultant) and should follow the steps outlined below.

Prior to opening time:

- A designated agency representative should prepare a “tender opening record form” and record:

- the names and signatures of the agency (tendering authority) personnel in attendance

- the names of all people in attendance, along with their company or other affiliations

- the official closing time of the “receipt of tenders”, and

- the name of each bidder, along with the amount, revised price (if any) and total of each bid

The agency also should verify the correct time prior to opening to ensure the tenders are not opened prematurely.

The Opening:

Tenders may be opened after the close of the bidding process is announced. The opening process should follow these steps:

- Each tender received in the form prescribed is opened and signed by each of the agency personnel present

- The presence of the bid bond is verified before the price is read out. If the bid bond is not present, the tender should not be read out but declared invalid

- Tenders are checked to ensure general compliance with the tender documents, and that the bidder is named and the signatures are present. If these items are not correct, the tender may be set aside for further evaluation

- The written and numerical amounts are checked to ensure they are the same

- When these requirements (1 to 4 inclusive) are fulfilled, the bid price is announced. If revisions are made prior to closing, then the revised bid price is announced as “We calculate the bid price to be $ ”

- Each tender amount is recorded on the tender opening record form

- When these steps (1 to 6 inclusive) are complete, each tender is carefully replaced in its envelope

The agency should then announce that:

- the tenders will be reviewed in detail

- all bidders will be notified of the results, and

- the opening procedures are now closed

The tenders should then be carefully secured to ensure they remain intact.

In the event that only one tender is received, the agency may open the tender without reference to the bidder.

All tenders submitted late should be returned to the sender – unopened by the tendering authority – together with a covering letters. Letters of notification should also be sent to bidders whose tenders are disqualified for other reasons.

A bidder who makes a serious and demonstrable mistake in a bid may be permitted to withdraw the bid without penalty, provided that:

- the agency is informed of the mistake promptly after bid closing and before the bid is opened, and

- where applicable, the agency has permission from its funding authority

Where mathematical errors occur in extending or calculating prices in the bid form, the unit prices or detail prices shall prevail, with the mathematical extension adjusted accordingly.

At the agency’s sole discretion, tenders may be disqualified or rejected for containing alterations, qualifications or omissions to the tender form or otherwise failing to conform to the tender documents. Agencies retain the right to waive minor clerical or technical irregularities in the tender form, as long as they do not create an unfair competitive advantage.

Should two or more bids be the same, the relative advantages of each bid’s proposed time schedule should be used to determine the successful low bidder.

8.5.3.3.7 Post Bid Closing Amendments

If the tendering process does not generate a bid price acceptable to the agency, and design documents would have to be substantially changed to reach an acceptable price, then all bids should be rejected and bidders so notified.

8.5.3.3.8 Contract Award Criteria (Qualified Low Bid)

Public sector contracts are awarded based on the lowest qualified bid that meets the tender documents’ terms and conditions.

The lowest or any tender may not necessarily be accepted.

8.5.3.3.9 Post Tender Negotiations

Prior to contract award, agencies may negotiate certain items (e.g. separate and alternate prices) or changes to the tender documents with the lowest qualified bidder.

If the negotiations fail to produce an acceptable price, all tenders are rejected and the bidders so notified.

Bids should be held irrevocable for a defined period (typically 30 days). If a contract is awarded after the period expires, the bidder must confirm in writing that the bid price remains valid and security requirements can still be fulfilled.

The actual award process begins with a letter of award, stating that the agency accepts the bidder’s offer to do the work for the agreed amount and is prepared to sign an agreement. The letter should be followed by a signed contract.

8.5.3.3.11 Contract Management (Build) Phase

This phase begins once the contract is awarded and concludes when the completed project is accepted, as described below.

8.5.3.3.12 Contract Management

Contracts must be administered in accordance with their terms. Changes to contracts (e.g. change orders) should be kept to a minimum and any disputes that arise should be dealt with fairly and promptly.

8.5.3.3.13 Acceptance of the Project

A payment certifier (typically the agency’s prime consultant) must determine when substantial performance, as defined in the Builders Lien Act, is reached. In general terms, it occurs when a building is ready to serve its intended purpose and the proponent has met the terms of the contract.

7. Project Personnel & Management < Previous | Next > 9. Budget & Cost Management