Module 4: Dam Failures

This module will provide an overview on notable dam failures in British Columbia, and in other areas internationally. Dam failures frequently occur, whether it is a small or large dam. Many dam failures are not frequently covered by media outlets, as the majority of failures do not directly cause loss of life.

Dams fail due to improper design, construction, maintenance, and management. The average age of an embankment dam is 50 years old. In British Columbia, there is an average of 1-2 failures per year not including incidents and hazards. Dams will deteriorate if allowed to, and require constant maintenance and routine inspections. Dam failures can cause loss of life, economic loss, and environmental loss. Dam owners who do not show due diligence in British Columbia may be held liable for any damages caused by a dam failure. Owners who have the combination of proper dam safety knowledge and regulator compliance in British Columbia can greatly minimize the risk that dams pose to the public and avoid significant dam catastrophes.

Testalinden 2010

At approximately 2:15pm on Sunday June 13, 2010, a privately-owned earthen dam on a man-made reservoir on Testalinden Creek failed, causing an enormous debris and mud torrent that severely impacted a number of homes and an agricultural area eight kilometers south of Oliver, British Columbia.

Initial reports indicated that a local hiker noticed water overflowing a roadway on Friday June 11 and reported this observance to a local tourism office. This information was then relayed to the local RCMP detachment, which referred it to the District Office of the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations & Rural Development. Unfortunately, the message was not received by appropriate authorities until after the dam failure event on Sunday June 13, at which point the immediate requirement was for emergency response and evacuation of those impacted.

The days leading up to the breach of Testalinden Dam saw heavy rains in the area. On June 11, 2010, a hiker noticed that Testalinden Lake was full of water and that the water was overflowing onto the road. The water flow was enough to carve a 12 inch channel across the roadway. He commented that he could usually see a culvert there but that the culvert was now under water. He added that normally the culvert was flowing all year round.

The Testalinden dam failure greatly impacted the dam safety program of British Columbia, and led to the revision of the Dam Safety Regulation, which was finalized in 2016 under the Water Sustainability Act. Many of these changes focus on stronger compliance measures by smaller dam owners and align with guidelines set by the Canadian Dam Association guidelines.

Teton 1976 (Idaho, US)

On Saturday June 5, 1976 at 7:30 a.m, a muddy seepage leak appeared, suggesting sediment was in the water, but engineers did not believe there was a problem. By 9:30 a.m. the downstream face of the dam had developed a wet spot which began to discharge water at 20 to 30 cubic feet per second and the embankment material began to wash out. Crews with bulldozers were sent to plug the leak, but were unsuccessful. Local media appeared at the site at 11:15 and officials told the county sheriff's office to evacuate downstream residents. Work crews were forced to flee on foot as the widening gap, now larger than a swimming pool, swallowed their equipment. The operators of two bulldozers caught in the eroding embankment were pulled to safety with ropes.

The Teton dam failure was a tragic event, that highlights the importance of being critically aware of sediment laden seepage. The dam failed only five hours after such seepage was discovered. It is also worthy to note that the dam failed upon its first reservoir filling. Rapid fillings and draw downs of the reservoir come with many risks that may impact the integrity of the dam, along with other structural concerns.

The collapse of the dam resulted in the deaths of 11 people and 13,000 cattle. The dam cost about $100 million to build and the federal government paid over $300 million in claims related to its failure. Total damage estimates have ranged up to $2 billion. The dam has not been rebuilt.

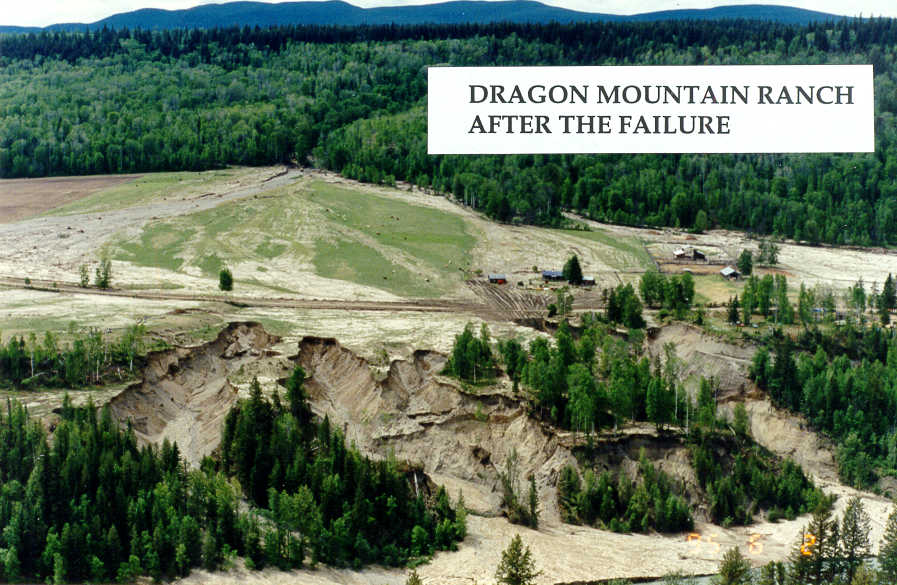

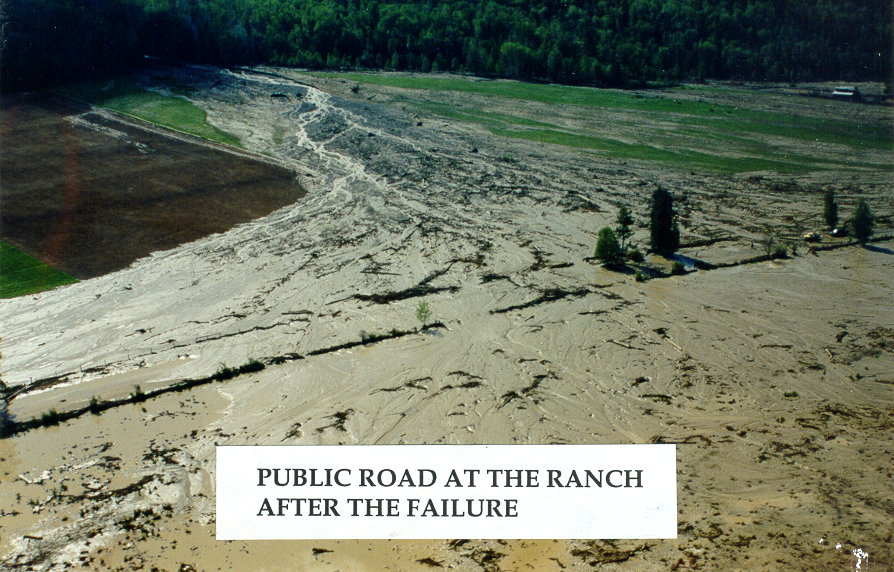

Cannon Creek 1995

On May 27 at around 8 a.m, a 6 m high earth-filled irrigation dam about 45 km east of Quesnel failed. It caused approximately $500,000 of damages to the road system and other properties. The sudden release of the storage killed 48 head of cattle, destroyed 1.5 km of a public road and damaged between 100-200 ac. (40-80 ha) of hayfields. Besides causing cattle and infrastructure losses, it rendered half of the 600 ac. (240 ha.) Buchanan Ranch useless and dumped thousands of tons of gravel and debris into the Quesnel River, about 300 ft. (90 m) below the ranch. A day prior to the dam burst, a deal to sell the ranch fell through. Part of the reason for the failed real estate transaction were problems cited with the dam.

The dam was on a sloping hillside about 1,000 ft. (300 m) above the ranch, and 2 km south. It held back a 12 to 15-ac. (4.8-6 ha) body of water, 20 ft. (6 m) deep. The torrent cut a quarter-mile (400 m) swath down towards the Quesnel River. Some 700,000 m3 of material went into the river, turning it dark for 45 km.

About a 40-ft. (12 m) section of Hydraulic Road disappeared into an instant 25-ft. (7.5 m) deep ravine. A 20-ft. (6 m) piece of the roadway holding the lake blew away. According to district highways manager, it would take up to two weeks and up to $250,000 to stabilize Hydraulic Road. Approximately 2 km of the road had to be reconstructed. Road damage was later estimated at less than $200,000.

The outburst peaked at about 8:15. A wall of water, trees and debris headed directly towards the ranch where three occupants of the ranch narrowly escaped. Fifteen minutes later, the flow was beginning to back off and by 9 a.m. it was reduced to a trickle. Much of the ranch’s northern pasture turned into a series of ravines. In some places, these gorges dropped 300 ft. (90 m) deep, measuring more than 100 ft. (30 m) across.

For a week prior to the failure, the owners had experienced trouble with their irrigation dam. Just days earlier, a diver had been hired to take a look and repair a faulty gate valve at the dam. He reported that water was running under the 16-in. (40 cm) culvert. Material was deposited around the culvert and the valve was repaired. At that point, the culvert was considered working properly.

Brazil 2019

On Jan. 25, a mining dam that sat above Brumadinho, a large town in southeastern Brazil, collapsed and unleashed a tidal wave of waste and mud that engulfed homes, businesses and residents in its path. Over 100 people were killed.

It was one of the deadliest mining accidents in Brazilian history — a tragedy, but not a surprise, experts said during an investigation into the dam’s collapse. All the elements of a potential catastrophe had been present, and warning signs overlooked, for years.

The Brazil 2019 failure highlights improper management and maintenance of key issues. There were multiple reports of leaks and seepage, however the dam practices to repair and maintain these problems were ineffective and contrary to best engineering practices. It is important to note that this was a tailings dam, as opposed to a water embankment dam.

As stated above, dam failures occur frequently around the world and may not receive the proper media coverage to highlight the importance of dam safety and public safety. An example would be the Spencer Dam Failure in Nebraska of March 2019, a failure which was buried under other news events during that time. With proper dam safety knowledge and regulator compliance, dam owners in British Columbia can greatly minimize the risk that dams pose to the public and avoid any dam catastrophe.