Part 1: RoadSafetyBC’s Driver Medical Fitness Manual Introduction and Principles

1.1.1 How this manual is organized

This Manual consists of 4 parts.

This first part, Background, provides the necessary context for the remainder of the manual. The 3 chapters within this part are:

- 1.1: Introduction, which explains the purpose of the Manual and developments that have influenced RoadSafetyBC’s approach to driver fitness

- 1.2: The authority for the CCMTA standards, which provides an overview of the mandate of the CCMTA and the relationship between driver fitness policy in individual Canadian jurisdictions and the CCMTA standards

- 1.3: The B.C. Driver Medical Fitness Program, which provides an overview of the authority for, and activities of, the Driver Medical Fitness Program in British Columbia, as well as the roles and responsibilities of the various Driver Medical Fitness Program partners, and

- 1.4: Driver Medical Fitness Program Principles, which are the foundation for the policies and procedures

The second part, Policies and Procedures, outlines RoadSafetyBC’s policies and procedures applicable to each of the four activities of the Driver Fitness Program. The five chapters within this part are entitled:

- 2.1: Introduction to the Policies and Procedures

- 2.2: Screening Policies. Because screening is largely conducted by RoadSafetyBC’s Driver Fitness Program partners, procedures are not included in this chapter.

- 2.3: Assessment Policies and Procedures

- 2.4: Determination Policies and Procedures, and

- 2.5: Reconsideration Policies and Procedures

The third part of the Manual contains the medical condition chapters. The first chapter in this part, Chapter 1, is an introduction that outlines the purpose and the format of the medical condition chapters. Chapter 2: Medical Conditions at-a-Glance, is a table that may be used as a quick reference to determine how each of the identified medical conditions affects the functions necessary for driving.

Chapters 3 through 22 are the actual medical condition chapters.

The fourth part of the Manual contains the Appendices. These include:

- Appendix 1: BC Licence Classes, which describes the various classes of driver’s licences

- Appendix 2: Canada – US Reciprocity Agreement

- Appendix 3: The Relationship between BC Driver Fitness Policy and Policy in other Jurisdictions, which is primarily of relevance to commercial drivers who wish to drive in the United States,

- Appendix 4: Excerpts from the MVA that are relevant to the Driver Medical Fitness Program

- Appendix 5: Aging Drivers, which describes the research in support of routine screening of drivers who are 80 years of age and older

1.1.2 Purpose of this Manual

This Manual documents the Driver Medical Fitness Program policy and procedures of RoadSafetyBC. It is to be used by RoadSafetyBC staff to supplement CCMTA’s Guidelines when making driver fitness determinations.

1.1.3 A changing approach to driver fitness

A Supreme Court of Canada decision established the requirements to individually assess drivers. The 'Grismer'* case held that each driver must be assessed according to the driver's own personal abilities rather than presumed group characteristics.

(*British Columbia (Superintendent of Motor Vehicles) v. British Columbia (Council of Human Rights), [1999] 3 S.C.R.868)

RoadSafetyBC has adopted a functional approach to driver fitness. This means that RoadSafetyBC assesses the impact of a medical condition on the functions necessary for driving when making driver fitness determinations.

Where a medical condition results in a persistent impairment of the functions necessary for driving, RoadSafetyBC bases its driver fitness determination on the results of functional assessments that observe or measure the functions necessary for driving. If the impairment is episodic, the impact of the medical condition on the functions necessary for driving cannot be functionally assessed and RoadSafetyBC bases its driver fitness determination on the results of medical assessments.

RoadSafetyBC has increased its emphasis on using research evidence, where it exists, as the basis of its driver fitness policies. Each medical condition in Part 3 of this Manual is included because the best available evidence shows that the medical condition causes impairment of one or more of the functions necessary for driving or has been associated with an elevated risk of crash or impaired driving performance.

Chapter 1.2: The Authority for the CCMTA standards

1.2.1 Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators

The Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators is an organization comprising representatives of provincial, territorial and federal governments of Canada which, through the collective consultative process, makes decisions on administration and operational matters dealing with licensing, registration and control of motor vehicle transportation and highway safety. It also includes associate members from the private sector and other government departments whose expertise and opinions are sought in the development of strategies and programs.

CCMTA receives its mandate from, and reports to, the Council of Ministers Responsible for Transportation and Highway Safety.

The executive of CCMTA is made up of a fourteen-member Board of Directors, each representing his/her government who to attend to the overall management of the organization. The Board is responsible for providing overall guidance and specific direction to the standing committees. It reports to the Councils of Ministers and Deputy Ministers through the President of CCMTA, who is also Chair of the Board.

Reporting to the CCMTA Board, the work of CCMTA is conducted by three permanent standing committees. The mandates of the standing committees are as follows:

- The Standing Committee on Drivers and Vehicles (D&V) is responsible for all matters relating to motor vehicle registration and control, light vehicle standards and inspections, and driver licensing and control.

- The Standing Committee on Compliance and Regulatory Affairs (CRA) is concerned with the compliance activities of programs related to commercial driver and vehicle requirements, transportation of dangerous goods and motor carrier operations in order to achieve standardized regulations and compliance programs in all jurisdictions.

- The Standing Committee on Road Safety Research and Policies (RSRP) is responsible for coordinating federal, provincial and territorial road safety efforts, making recommendations in support of road safety programs, and developing overall expertise and strategies to prevent road collisions and reduce their consequences.

CCMTA's Vision is to have the safest and most efficient movement of people and goods by road in the world. Its mission is to provide a national forum for development of public policy and programs for road safety and driver and vehicle licensing.

1.2.2 The Mandate of the CCMTA Driver Fitness Overview Group (DFOG)

The Driver Fitness Overview Group reports to the CCMTA Standing Committee on Drivers and Vehicles. Members are expected to be a mix of various types of expertise on driver fitness and consist of administrators and medical professionals representing licensing authorities. Medical professionals can include physicians, occupational therapists and nurses.

The mandate of the CCMTA DFOG is to derive a set of driver fitness policies and for jurisdictional use that incorporate the best ideas and principles included in the currently available literature and maintain their currency through periodic review.

Specific responsibilities include:

- Strategies for all driver fitness issues using a driver fitness model which is a functional approach to determine the impact on the functions of driving.

- Uniform medical standards to be used by administrators in assessing a person's medical fitness to operate a motor vehicle.

- and manage the CCMTA Medical Standards document.

- as liaison on behalf of CCMTA with other organizations (e.g.: Canadian Medical Association, U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FMCSA), medical specialty societies).

- as a clearing house for all activities under its purview.

- Identify areas of concern and direct activities accordingly.

1.2.3 The relationship between individual Canadian jurisdictions` driver fitness policies and the CCMTA standards

All Canadian provinces and territories have the authority to establish their own driver fitness policies and procedures. All have a medical review board or unit acting in an advisory capacity to the jurisdiction's licensing body (the Registrar) on medical matters that may affect a person's fitness to drive. However, in order to support a consistent approach to driver fitness across the country, the provinces and territories agreed to publish CCMTA Medical Standards for Drivers.

In 1985, medical standards for drivers were identified as part of the National Safety Code (NSC) initiative undertaken to achieve uniformity among the provinces and territories, on many aspects relating to the administration of drivers and vehicles. The rationale being that licence transfers upon a change of province of residence should not be complicated by divergent medical requirements. The classification of driver licences adopted by the provinces and territories as part of the NSC is shown in Appendix 1. A Medical Advisory Committee (MAC), comprised of physicians appointed by each jurisdiction, was created to identify and reconcile interprovincial medical standard variances and produce a harmonized standard. The basis for developing the harmonized medical standards was primarily publications from the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) and other medical specialty associations.

In 2000, CCMTA created a Driver Fitness Project Group to carry out a standards review, with attention to risk, compensation, accommodation, functional focus and whether and how to assess for each medical standard. This approach reflected recent trends relating to evidence based medicine rather than standards in determining an individual’s fitness to drive.

In 2008, a Driver Fitness Overview Group in 2008 was formed to:

- Consolidate the work of the MAC and Driver Fitness to avoid duplicate work, duplicate reporting and record keeping and to house all medical related issues under the same umbrella, and

- Produce one central CCMTA medical document.

In 2011 the Driver Fitness Overview Group developed new driver fitness standards in conjunction with subject matter experts including researchers, general practitioners and medical specialists, and administrators from Canadian driver fitness authorities. The standards are intended as a guide in establishing basic medical qualifications to drive for both commercial and non-commercial drivers and are intended for use by both physicians and driver fitness authorities.

Although no jurisdiction in Canada is legally required to adopt the CCMTA standards, the majority are adopted by the driver fitness authorities. This achieves a uniformity of standards across Canada which supports both road safety and inter-provincial harmonization.

All medical standards, and subsequent changes, contained in Part 3 of this document are approved by all jurisdictions through a ballot process which requires a two thirds majority for approval.

1.2.4 The relationship between Canadian jurisdictions’ driver fitness standards for commercial drivers, the CCMTA standards and the North American Free Trade Agreement

Under the North American Free Trade Agreement, the United States and Canada reached agreement on reciprocity of the medical fitness requirements for drivers of commercial motor vehicles (CMVs) effective March 30, 1999. The countries determined that the medical provisions of U.S. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations (FMCSRs) and the Canadian National Safety Code (NSC) are equivalent (see Appendix 2).

There were three exceptions for Canadian drivers. Those who are (1) insulin-treated diabetics, (2) hearing-impaired at a defined level, or (3) have epilepsy are not permitted to operate CMVs in the United States.

U.S. regulations prohibit individuals with those conditions from operating CMVs in the United States while they are allowed to drive commercial vehicles in Canada.

Also drivers from either country operating under a medical waiver or who are operating under medical grandfather rights are prohibited from operating in international commerce.

Because the reciprocal agreement between the United States and Canada identifies the CCMTA standards as the standard for commercial drivers, this means that regardless of individual provincial or territorial standards, drivers of CMVs must meet or exceed the CCMTA standards if they drive in the United States.

Commencing in January 2012, both countries agreed to adopt a unique identifier code to be displayed on the licence and the driving record to identify a commercial driver who is not qualified or disqualified from operating a commercial vehicle in the other country.

In Canada, the identifier code will be “W”, and defined as: “restricted commercial class – Canada only”. In the United States, the identifier code “V” will indicate the U.S. driver is only allowed to drive in the U.S. and is not medically qualified to drive in Canada.

1.3.1 The legal and policy authority for the Driver Medical Fitness Program in British Columbia

The Motor Vehicle Act [OSMV 1996] Chapter 318

The Motor Vehicle Act (MVA) provides the statutory authority for the Driver Medical Fitness Program.

Section 25 describes the statutory requirements regarding the application for and issuance of a driver’s licence. It sets out the authority of the Superintendent to determine that applicants for various classes of driver’s licences are able and fit to drive safely and to require an individual to be examined as to their fitness and ability to drive. It also authorizes the Superintendent to impose restrictions and conditions. Relevant portions of section 25 are reproduced in Appendix 4.

Section 29 extends the authority of the Superintendent to determine whether holders (post-licence) of various classes of driver’s licences are able and fit to drive safely and authorizes the Superintendent to require a holder to be examined as to their fitness and ability to drive. The full text of section 29 is in Appendix 4.

Section 92 authorizes the Superintendent to direct the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia (ICBC) to cancel any class of driver’s licence, cancel and issue a different class of driver’s licence or prohibit a driver if the driver has a medical condition affecting fitness and ability to drive. It also authorizes the Superintendent to direct ICBC to cancel a driver’s licence if the driver does not submit to an exam the Superintendent has required to assess fitness and ability to drive safely. The full text of section 92 is in Appendix 4.

The relationship between the MVA and RoadSafetyBC driver fitness policy plays an important role in the work of a regulatory body. To understand this role, RoadSafetyBC decision-makers need to be familiar with the relationship between the MVA and RoadSafetyBC policy

Legislation

The primary statement of law is written in legislation. Legislation provides ‘rules’ that must be followed without exception or the exercise of discretion. Because legislation sets out ‘rules,’ it is broadly written. The finer points of law are left to be defined and set out in regulation and policy. This allows for greater flexibility and, in the case of policy, the exercise of discretion.

Regulations

Regulations primarily fill in the details of legislation. Like legislation, regulations are law. However, they are subordinate legislation made under the authority of the statute. An advantage of regulations over legislation is that they are easier to change or repeal. By amending regulations, the government can adapt quickly to changing program needs and operational issues. There are no regulations under the MVA relating to driver fitness.

Policy

Driver Medical Fitness Program policy is not passed by the government but is developed and approved within RoadSafetyBC. Policy is generally binding on program operations and will generally be upheld by a judicial or quasi- judicial body.

Policy is how RoadSafetyBC implements the Superintendent’s authority under the MVA. The MVA authorizes the Superintendent to require a medical examination before granting a driver's licence. The policies articulated in this Manual provide the level of detail required by RoadSafetyBC to assess and determine driver fitness.

Policy can take many forms. In Chapters 2.1 through 2.5 of this Manual, Driver Medical Fitness Program policy is presented as individually numbered policy statements. In the medical condition chapters, the BC Driver Medical Fitness Program policy is presented as:

- CCMTA STANDARD medical condition guidelines

- BC Guidelines for assessments and fitness determination

- Conditions and Restrictions Guidelines; and

- RoadSafetyBC re-assessment interval guidelines

When making driver fitness determinations, RoadSafetyBC decision-makers will generally refer to both the general policy statements from Chapters 2.1 through 2.5 and the specific guidelines relevant to particular medical conditions from the medical condition chapters. Because each driver is unique and determinations are made on an individual basis, the medical condition chapters present “guidelines” rather than hard rules that must be followed without exception.

RoadSafetyBC decision-makers need the policies and guidelines in this Manual to provide a framework for the exercise of their discretionary powers. If there are no criteria to guide decisions, the decisions may be arbitrary and, over time, inconsistent. The policies in this Manual provide a framework for the exercise of discretion by RoadSafetyBC staff responsible for driver fitness determinations.

1.3.2 Driver Medical Fitness Program overview

From 2010 to 2014, the Driver Medical Fitness Program assessed approximately 150,000 drivers annually. In an average year, about 5,000 drivers had their driving privileges cancelled for fitness reasons or for not complying with a request for assessment and about 1,000 drivers voluntarily surrendered their licence.

Approximately 600 drivers had their driving privileges class reduced.

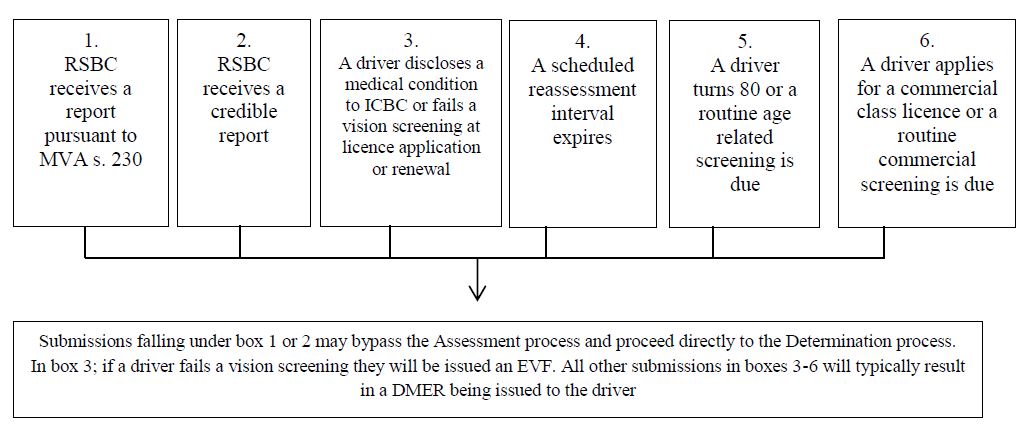

The flowcharts following this section of text highlight the four key activities of the Driver Medical Fitness Program: Screening, Assessment, Determination and Reconsideration.

Screening identifies:

- Individuals who have a known or possible medical condition that may impair their functional ability to drive,

- Commercial drivers, and

- Aging drivers

Screening policies are documented in Chapter 2.2 of this Manual.

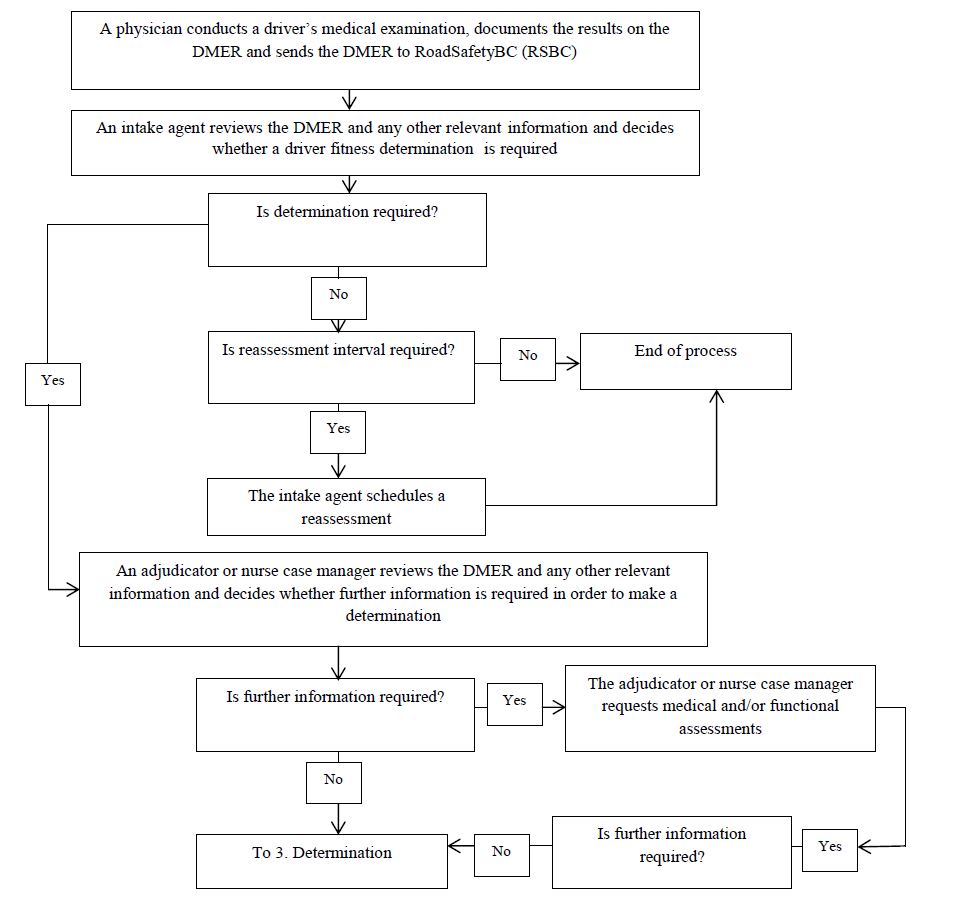

Assessment is the process of collecting information required to make a driver fitness determination. The key assessment used for driver fitness determinations is a driver’s medical examination completed by a physician – usually a driver’s general practitioner or specialist. Information gathered during the medical examination is documented on the Driver Medical Examination Report (DMER). A variety of other assessments may also be required, such as specialist examinations or on-road assessments. Assessment policies and procedures are documented in Chapter 2.3 of this Manual.

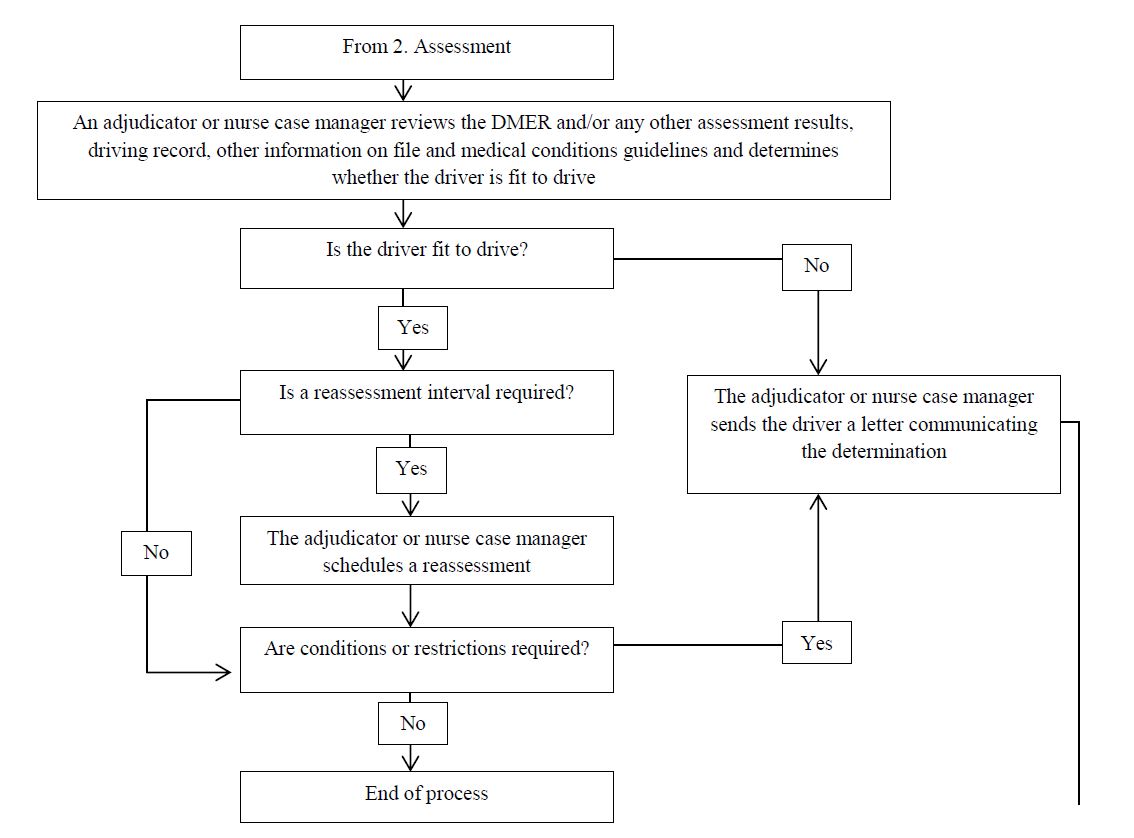

Determination involves reviewing:

- The information obtained from assessments,

- Any other relevant file information, such as driving history, and

- The medical condition guidelines outlined in Part 3 of this Manual and determining whether an individual is fit to drive.

Policies and procedures that govern the determination process are outlined in Chapter 2.4 of this Manual.

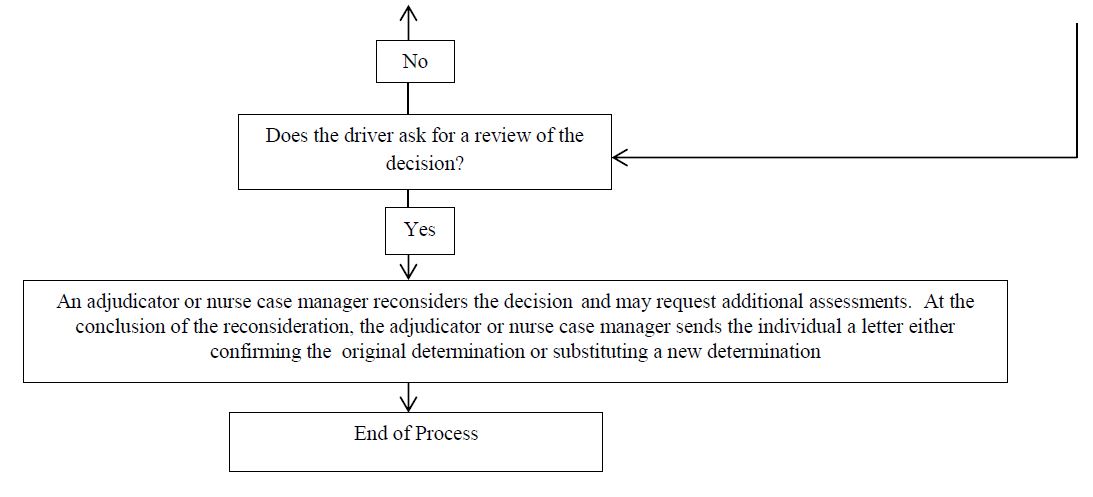

Reconsideration is the process of reviewing a driver fitness determination upon request of an individual who was found not fit to drive, or who had restrictions or conditions imposed. Policies and procedures that govern the reconsideration process are outlined in Chapter 2.5 of this Manual.

1. Screening

2. Assessment

3. Determination

4. Reconsideration

1.3.3 Roles and Responsibilities

RoadSafetyBC works in partnership with ICBC and other agencies, such as the BC Driver Fitness Advisory Group, the Doctors of BC and the BC College of Physicians and Surgeons to implement and administer the Driver Medical Fitness Program. The following paragraphs highlight the roles and responsibilities of the key participants in the Driver Medical Fitness Program.

BC Driver Fitness Advisory Group

The Driver Fitness Advisory Group consists of RoadSafetyBC staff, and representatives from the Doctors of B.C., College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C., B.C. Psychological Association, B.C. Nurse Practitioner Association, Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists and the College of Occupational Therapists of B.C. The advisory members serve as a valued source of input into the ongoing development of the CCMTA Standards and are consulted and engaged in discussion when new standards are being considered and ballots for change are circulated by the CCMTA. Advisory group members also offer ideas, provide advice and consult with RoadSafetyBC on the development of driver fitness strategic initiatives.

RoadSafetyBC

On a day-to-day basis, driver fitness determinations are made by RoadSafetyBC nurse case managers and adjudicators. The roles of various RoadSafetyBC staff within the Driver Medical Fitness Program are described in the paragraphs below.

Intake agents perform an initial review of DMERs and other assessment results that are sent to RoadSafetyBC. They identify those individuals who clearly meet the medical condition guidelines outlined in Part 3 of this Manual without the need for further assessment or a driver fitness determination.

They identify and forward cases that require an exercise of discretion to adjudicators and nurse case manager.

The procedures that guide the work of intake agents are documented in the:

- Intake Agent Triage Sort Procedures,

- Intake Agent Guidelines for Assessing Fitness to Drive, and

- Intake Agent Procedures Manual.

Adjudicators are responsible for making decisions on less medically complicated cases; they may exercise discretion in decision-making.

Nurse case managers are registered nurses responsible for making decisions on more medically complicated cases; they may exercise discretion in decision making.

ICBC

In partnership with RoadSafetyBC and under delegation, ICBC performs some administrative functions for the Driver Medical Fitness Program. In carrying out powers or responsibilities delegated to it under section 117(1) of the MVA, ICBC must act in accordance with any directives issued by the Superintendent.

ICBC also plays an important role in screening. Through direct questioning on a day-to-day basis, either at the time of initial licensing or licence renewal, ICBC Points of Service staff identify individuals who have a medical condition that may impair the functions necessary for driving. An individual applying for a driver’s licence must also take a vision screening test at the ICBC Point of Service. If an individual discloses a medical condition or fails the vision screening test, ICBC staff may initiate a DMER or, at the direction of RoadSafetyBC, may not issue a driver’s licence until RoadSafetyBC indicates that the individual is fit to drive.

As the driver licensing authority for the province, ICBC has its own requirements that may impact individuals who have been the subject of an RoadSafetyBC driver fitness determination. For example, ICBC will not issue a licence to an individual who hasn’t held a licence for more than 3 years unless the individual takes an ICBC road test. This means that RoadSafetyBC may determine that an individual whose licence was cancelled for fitness reasons is now fit to drive because of an improvement in their medical condition, but ICBC may require successful completion of a road test before issuing a new licence.

Medical practitioners

Medical practitioners also play a role in screening. Under section 230 of the MVA, registered psychologists, optometrists, medical practitioners, or nurse practitioners must report to RoadSafetyBC if:

- A patient has a medical condition that makes it dangerous to the patient, or to the public, for the patient to drive a motor vehicle, and

- Continues to drive after the psychologist, optometrist or medical practitioner, or nurse practitioner warns the patient of the danger.

The full text of section 230 is included in Appendix 4.

In addition to this reporting duty, medical practitioners or nurse practitioners conduct assessments and provide information to RoadSafetyBC on a patient’s prognosis, treatment and extent of impairment. Sometimes medical practitioners or nurse practitioners are asked to comment directly on driving ability.

Allied health care practitioners

Allied health care practitioners such as occupational therapists, driver rehabilitation therapists and physiotherapists may be asked to conduct assessments of drivers.

Individual drivers

When applying for or renewing a British Columbia driver’s licence of any class, individuals are asked if they have any medical conditions that affect driving. When an applicant reports a medical condition that could affect the functions necessary for driving, a DMER is generally issued. The individual is responsible for taking this to their doctor to be completed.

Based on information provided by the physician on the DMER, an individual may be required to submit to additional assessments for RoadSafetyBC to determine their fitness to drive.

Once a determination is made, individuals must comply with any conditions or restrictions imposed by RoadSafetyBC or, if their licence is cancelled, surrender the licence to ICBC. Individuals are informed of conditions, restrictions and licence cancellations in a letter from RoadSafetyBC.

Commercial drivers who wish to drive outside of BC

Commercial drivers who wish to drive outside of BC must familiarize themselves with any medical condition-related restrictions or prohibitions applicable in other jurisdictions. Appendix 3 provides an overview of the relationship between BC Driver Medical Fitness Program policy and policies applicable to commercial drivers who wish to drive in the United States.

1.4.1 Overview

RoadSafetyBC has articulated the following four principles that guide the Driver Medical Fitness Program. By following these principles, RoadSafetyBC ensures that drivers are given the maximum licensing privilege possible taking into account their medical condition, its impact on the functions necessary for driving and the driver’s ability to compensate for the condition.

Risk management

While public safety is a prominent consideration when making driver fitness determinations, the requirements of administrative fairness must also be applied when making driver fitness determinations. Further, a degree of risk to public safety may be tolerated in order to allow a broad range of people to drive.

Functional approach

Driver fitness determinations will be based primarily on functional ability to drive, not diagnosis.

Individual assessment

Driver fitness determinations will be based on individual characteristics and abilities rather than presumed group characteristics and abilities.

Best information

Driver fitness determinations will be based on the best information that is available.

Each of these principles is explained in detail in the following sections.

1.4.2 Risk Management

While public safety is a prominent consideration when making driver fitness determinations, the requirements of administrative fairness must also be applied when making driver fitness determinations. Further, a degree of risk to public safety may be tolerated in order to allow a broad range of people to drive.

In Grismer, the Supreme Court of Canada indicated that people with some level of functional impairment may have a licence because society can tolerate a degree of risk in order to permit a wide range of people to drive. In its decision, the court states:

“Striking a balance between the need for people to be licensed to drive and the need for safety of the public on the roads, [the Superintendent] adopted a standard that tolerated a moderate degree of risk. The Superintendent did not aim for perfection, nor for absolute safety. The Superintendent rather accepted that a degree of disability and the associated increased risk to highway safety is a necessary trade-off for the policy objectives of permitting a wide range of people to drive and not discriminating against the disabled. The goal was not absolute safety, but reasonable safety.” [para. 27]

To achieve this balance between road safety and an individual’s need to drive, RoadSafetyBC applies a risk management approach to driver fitness determinations. This means that, when making a driver fitness determination, RoadSafetyBC considers the degree of risk presented by an individual driver. If RoadSafetyBC’s analysis indicates a high degree of risk, the individual is not fit to drive.

How does RoadSafetyBC determine the degree of risk presented by an individual driver?

Risk is often defined as a formula; that is, risk is the likelihood of an uncertain event multiplied by the consequence if the event were to take place. This means that a highly likely event with serious consequences is a greater risk than an unlikely event with minor consequences.

Unfortunately, there are no reliable formulas to calculate risk as it relates to fitness to drive. The impact of a medical condition may be specific to an individual and the ability to compensate for the medical condition may also vary by individual. As well, because the driving environment is complex and continuously changing, it is difficult to determine exactly what level of impairment means a person is not fit to drive.

Because of these limitations, RoadSafetyBC cannot precisely calculate the risk presented by a driver with a particular medical condition. However, RoadSafetyBC can determine the general degree of risk presented by a driver with a particular medical condition by using a risk assessment analysis that takes into account:

- Research associating the medical condition with adverse driving outcomes or evidence of functional impairment,

- Expert opinion regarding the degree of risk associated with the medical condition at various severity levels, and

- The individual characteristics and abilities of each driver, for example whether the driver:

- Is a commercial or private driver,

- Can compensate for the functional impairment,

- Is compliant with their treatment regime, and

- Has insight into the impact that their medical condition may have on driving.

The policies outlined in this manual guide RoadSafetyBC decision-makers in determining the degree of risk presented by individual drivers. The medical condition guidelines included in the medical condition chapters of this manual are based on the best available evidence regarding degree of risk and identify where the use of conditions, restrictions and/or compensation strategies may be appropriate to reduce risk. If the risk associated with a medical condition at a certain severity level is high, and the risk cannot be reduced through the use of conditions, restrictions and/or compensation strategies, the guidelines indicate that an individual is not fit to drive. By applying the medical condition guidelines, RoadSafetyBC decision-makers are practicing risk management.

1.4.3 Functional approach

Driver fitness determinations will be based on a functional approach to driver fitness.

RoadSafetyBC takes a functional approach to determining driver fitness. This means that, when making driver fitness determinations RoadSafetyBC assesses the effect(s) that a medical condition has on the functions necessary for driving.

The functions necessary for driving are cognitive, sensory (vision) and motor (including sensorimotor).

Each of these functions is described below. Although the functions necessary for driving are described individually, driving is a complex perceptual-motor skill which usually takes place in a complex environment and which requires the functions to operate together.

Cognitive functions

The cognitive functions that are the most relevant to the driving task are: Attention (divided, selective, sustained)

Divided attention

- The ability to attend to two or more stimuli at the same time. Example: Attending to the roadway ahead while being able to identify stimuli in the periphery

Selective attention

- The ability to selectively attend to one or more important stimuli while ignoring competing distractions. Example: The ability to isolate the traffic light from among other environmental stimuli

Sustained attention

- Also referred to as vigilance. It is defined as the capacity to maintain an attentional activity over a period of time. Example: The ability to attend to the roadway ahead over an extended period of time.

Short-term or passive memory

- Refers to the temporary storage of information or the brief retention of information that is currently being processed in a person`s mind. Example: The temporary storage of information related to roadway sign information such as that related to freeway exits or construction areas; signs related to caution ahead, etc.

Working memory (the active component of short -term memory)

- Refers to the ability to manipulate information with time constraints/taking in and updating information. Example: Environmental information related to the driving task on a busy freeway.

Long-term memory

- Refers to memory for personal events (autobiographical memory) and general world knowledge (semantic memory). Long-term memory differs from short-term memory in a number of areas:

- Capacity – long-term memory has an unlimited capacity compared to the limited capacity of short-term memory;

- Duration – information stored in long-term memory is relatively stable for an indefinite period of time. Information in short-term memory, on the other hand, is very fleeting.

Example: Knowing your way from home to the grocery store; the meaning of traffic signs; and knowing the rules of the road.

Choice/complex reaction time

- Refers to the time taken to respond differentially to two or more stimuli or events. The time taken to respond and the appropriateness of the response are important within the driving context. Example: Responding when a cat darts onto the edge of the road at the same time a pedestrian steps onto the roadway.

Tracking

- Defined as the ability to visually follow a stimulus that is moving or sequentially appearing in different locations. Example: The ability to visually follow other cars on the road.

Visuospatial abilities

- Is a general category that refers to processes dependent on vision such as the recognition of objects, the ability to mentally rotate objects, determinations of relationships between stimuli based on size or colour. Example: Understanding where a tree and other objects are in relation to the car.

Executive functioning (see also central executive functioning below)

- Refers to those capabilities that enable an individual to successfully engage in independent, purposeful, and self-serving behaviours. Disturbances in executive functioning are characterized by disturbed attention, increased distractibility, deficits in self-awareness, and preservative behaviour.

Central executive functioning (see also executive functioning above)

- Refers to that part of working memory that is responsible for ‘supervising’ many cognitive processes including encoding (inputting information from the external world), storing information in memory, and retrieving information from memory.

- Central executive (CE) functioning includes abilities such as planning and organization, reasoning and problem solving, conceptual thought, and decision making. CE functioning is critical for the successful completion of tasks that involve planning or decision making and that are complex in nature.

Example: Making a left turn at an uncontrolled intersection.

Visual information processing

- Defined as the processing of visual information beyond the perceptual level (e.g., recognizing and identifying objects and decision making related to those objects).

- Visual information processing involves higher order cognitive processing. However, because of the visual component, references to visual information processing often are included within the visual domain.

Research indicates that individuals with progressive or irreversible declines in cognitive function cannot compensate for their cognitive impairment.

Motor functions (including sensorimotor)

Motor functions include:

Coordination

- The ability to execute smooth, accurate, controlled movements Example: executing a left hand turn; shifting gears, etc. Dexterity.

- Readiness and grace in physical activity; especially skill and ease in using the hands. Example: Inserting keys into the ignition; operating vehicle controls, etc.

Gross motor abilities

- Gross range of motion and strength of the upper and lower extremities, grip strength, proprioception, and fine and gross motor coordination.

Range of motion

- Defined as the degree of movement a joint has when it is extended, flexed, and rotated through all of its possible movements. Range of motion of the extremities (e.g., ankle extension and flexion are needed to reach the gas pedal and brake) and upper body range of motion (e.g., shoulder and elbow flexion are necessary for turning the steering wheel; elbow flexion is needed to turn the steering wheel; range of motion of the head and neck are necessary for looking at the side and rear for vehicles and for identifying obstacles at the side of the road or cars approaching from a side street).

Strength

- The amount of strength a muscle can produce. Example: Lowering the brake pedal.

- For many functions, muscle strength and flexibility often go hand in hand. Example: Getting in and out of the car; operating vehicle controls, fastening the seat belt, etc.

Flexibility

- The ability to move joints and muscles through their full range of motion (see examples above).

Reaction time

- The amount of time taken to respond to a stimulus Example: Depressing the brake pedal in response to a child running out on the roadway, swerving to avoid an animal on the road, etc.

Research on motor functions and driving indicates considerable variability in the association between the different motor functions and driving outcomes. Overall, the research suggests that a significant level of impairment in motor functions is needed before driving performance is affected to an unsafe level.

Sensorimotor

- For purposes of the Driver Medical Fitness Program, sensorimotor functions are considered as a subset of motor functions.

- Sensorimotor function is a combination of sensory and motor functioning for accomplishing a task.

- Sensorimotor functions are, for the most part, reflexive or automatic e.g., the response to your hand being placed on a hot stove; ability to sit upright, etc.

- Vestibular disorders and peripheral vascular diseases commonly result in sensorimotor impairments.

Sensory functions (Vision)

Visual functions important for driving include: Acuity

- The spatial resolving ability of the visual system, e.g., the smallest size detail that a person can see.

- Visual acuity typically is assessed by having the person read a letter chart such as the Snellen chart, where the first line consists of one very large letter, with subsequent rows having increasing numbers of letters that decrease in size.

Visual field

- Refers to an individual’s entire spatial area of vision when fixation is stable, e.g., the extent of the area that an individual can see with their eyes held in a fixated position.

Contrast sensitivity

- The amount of contrast an individual needs to identify or detect an object or pattern, e.g., the ability detects a gray object on a white background or to see a white object on a light gray background.

- An individual with poor contrast sensitivity may have difficulty seeing traffic lights or cars at night. Conditions such as cataracts and diabetic retinopathy affect contrast sensitivity.

Disability glare

- The degradation of visual performance caused by a reduction of contrast. It can occur directly, by reducing the contrast between an object and its background, i.e. directly affecting the visual task, or indirectly by affecting the eye Examples: The reflection of the sun from a car dashboard, and the view through a misted up windscreen.

Perception

- Refers to the process of acquiring, interpreting, selecting, and organizing sensory information.

Results from studies investigating the relationship between visual abilities and driving performance are, for the most part, equivocal. It may be, as suggested for motor abilities, that a significant level of visual impairment is needed before driving performance is affected.

1.4.4 Individual assessment

Driver fitness determinations will be based on individual characteristics and abilities rather than presumed group characteristics and abilities.

In the Grismer case, the Supreme Court of Canada held that each driver must be assessed according to the driver’s own personal abilities rather than presumed group characteristics. The case originated from a complaint to the BC Council of Human Rights regarding RoadSafetyBC’s cancellation of a driver’s licence. RoadSafetyBC had cancelled the licence because the driver’s vision did not meet the minimum standard established in the Guide. The Grismer decision is applicable to driver fitness determinations for individuals with persistent impairments. The courts have not yet considered the issue of individual assessments for drivers with episodic impairments.

The discrimination found in the Grismer case was not because RoadSafetyBC cancelled a licence but because the driver did not have the opportunity to prove through an individual assessment that he could be licensed without unreasonably jeopardizing road safety. The court held that RoadSafetyBC made an error when it adopted an absolute standard which was not supported by evidence.

Delivering the judgement of the Court, McLachlin J. wrote that: “Driving automobiles is a privilege most adult Canadians take for granted. It is important to their lives and work. While the privilege can be removed because of risk, it must not be removed on the basis of discriminatory assumptions founded on stereotypes of disability, rather than actual capacity to drive safely. … This case is not about whether unsafe drivers must be allowed to drive. There is no suggestion that a visually impaired driver should be licensed unless she or he can compensate for the impairment and drive safely. Rather, this case is about whether, on the evidence … [the driver] should have been given a chance to prove through an individual assessment that he could drive.”

The medical condition guidelines outlined in the medical condition chapters of this Manual are based on presumed group characteristics of individuals with each medical condition. However, consistent with the decision in Grismer, RoadSafetyBC makes driver fitness determinations on an individual basis. This is why the medical condition guidelines are called guidelines; they are a starting point for decision-making, but may not apply to every individual. Where appropriate, RoadSafetyBC utilizes individual assessments to determine whether an individual’s functional ability to drive is impaired and, if so, whether the individual can compensate for the impairment.

1.4.5 Best information

For each individual, RoadSafetyBC gathers the best information that is available and required to determine fitness. Depending upon the nature of the functional impairment, the best information may include results of specialized functional assessments that clearly indicate whether or not an individual is fit to drive. For other individuals and impairments there may be no scientifically validated assessment tools available that can accurately measure the impact of a medical condition on the functions necessary for driving. In the case of individuals with episodic impairments, RoadSafetyBC has to rely on the results of medical assessments as the best information available for determining fitness to drive.