Tax Interpretation Manual: Provincial Sales Tax Act - General Rulings

GR.2/R.1 - R.5: First Nations

R.1 History of the Exemption (Issued: 2014/04)

Section 87 of the Indian Act (Canada) provides:

(1) Notwithstanding any other Act of Parliament or any Act of the legislature of a province … the following property is exempt from taxation:

(a) the interest of an Indian or a band in reserve lands or surrendered lands; and

(b) the personal property of an Indian or a band situated on a reserve.

(2) No Indian or band is subject to taxation in respect of the ownership, occupation, possession or use of any property mentioned in paragraph (1)(a) or (b) or is otherwise subject to taxation in respect of any such property....

British Columbia has maintained the position that the Indian Act (Canada) exempts only those sales which occur on reserve lands. This position was supported by the Mary Leonard Court of Appeal decision of March 1984 which held that a deliberate distinction was made in the Indian Act between reserve and surrendered lands and that the limitation of the exemption to reserves in section 87(1)(b) of that Act was intentional.

As established originally under the Social Service Tax Act, the exemption for Indians was as follows:

- Exemption from tax applied only to goods located on a reserve at the time of sale.

- Goods delivered to a reserve after negotiations to the transaction had begun were subject to tax.

- If the purchaser solicited the goods to be delivered to the reserve for a possible sale, any resulting sales were subject to tax.

- Motor vehicles were exempt only if all aspects of the sale took place on an Indian reserve. If the vehicle was subsequently licensed for use on public highways, tax was payable on the purchase price.

- Merchants who brought goods onto a reserve for possible sale were required to obtain a completed "Certificate of Status as an Indian" from the Indian purchaser and to retain this certificate to substantiate non-collection of tax on that sale.

Over time, the following court actions and legislative changes to the Social Service Tax Act and the Indian Act (Canada) modified the branch's position:

Lillian Brown Court Decision, 1979: Effective March 11, 1980, all purchases of electricity by Indians or Indian Bands, where the electricity is delivered to a reserve and metered at the point of purchase (the reserve), became exempt from tax. This was later expanded to include natural gas.

Watts/Danes Court of Appeal Decision, 1985: As a result of this decision, goods located on a reserve at the time of sale became exempt from tax even if negotiations for the sale were entered into prior to the goods being situated on the reserve. In addition, motor vehicles purchased exempt and subsequently licensed for off reserve use became exempt from tax.

Metlakatla Ferry Service Court of Appeal Decision, 1987: The Metlakatla Indian Band challenged the province's assessment of tax on monthly lease payments for a vessel they used as a ferry between their reserve and the mainland. The court held that the "lease", not the "vessel", was being taxed and, because the lease interest is the property of the band, the lease payments are exempt.

Social Service Tax Act Amendments, 1987: Effective May 26, 1987, the Social Service Tax Act was amended to provide for the taxation of tangible personal property purchased or leased by Indians or Indian bands if the item was subsequently used off the reserve. These amendments partially counteracted the effects of the Watts/Danes 1985 Court Decision with respect to motor vehicles. Motor vehicles became subject to tax if licensed and insured for use on public highways.

The above amendments were introduced to maintain equity, particularly where First Nation contractors were in competition with non-First Nation contractors, and to maintain the historic, social, and constitutional policy of exempting Indians from tax only on tangible personal property located on a reserve.

Indian Act Amendments, Bill C-115, 1988: Effective June 28, 1988, the Indian Act (Canada) was amended to re-classify "conditionally surrendered land" as designated reserve lands and to provide designated reserve lands with the same status as reserve lands under the Act.

Metlakatla Indian Band Court of Appeal Decision, 1989: The court held that the 1987 amendments to the Social Service Tax Act were unconstitutional as they specifically singled out Indians, and that they were in conflict with section 87 of the Indian Act (Canada). As a result, tangible personal property originally purchased exempt on a reserve and subsequently used off reserve retains its exempt status. The 1987 amendments were repealed in 1992.

The branch was required to refund taxes paid under the 1987 amendments where there was adequate documentation substantiating that the sale took place on a reserve, that the tax was paid at the time of purchase, and that the purchaser is an Indian or Indian band.

Extension of Exemption to Designated Reserve Land, 1989: In accordance with the requirements of the 1988 amendments to the Indian Act (Canada), on June 27, 1989 the branch implemented procedures to enable Indians and Indian bands to make exempt purchases from retail outlets located on designated reserve lands.

Union of New Brunswick Indians Decision, 1996: In May 1996, the New Brunswick Court of Appeal decided the case of Union of New Brunswick Indians v. Minister of Finance. The issue was whether personal property purchased at an off-reserve location by an Indian or a band, but intended for ownership, possession, use, or consumption on a reserve, comes within the meaning of "situated on a reserve" in Section 87(1)(b) of the Indian Act and, therefore, qualifies for exemption. The court decided that the appropriate way of determining what property is exempt is to look at the pattern of use and safekeeping of the property. The court held that New Brunswick's social services and education tax (retail sales tax) did not apply to the acquisition of chattels destined for use or consumption on a reserve by an Indian or band. The Province of New Brunswick made application for leave to appeal this decision to the Supreme Court of Canada.

This decision did not apply to purchases made in British Columbia. British Columbia did not recognize the decision as binding because it was not a decision of the British Columbia courts, and it was appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada. British Columbia was granted leave to intervene in the appeal.

Supreme Court of Canada Decision, New Brunswick v. Union of New Brunswick Indians, 1998: On June 17, 1998, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the principle that the exemption provided under the Indian Act applies to purchases by Indians or Indian bands only if the goods are located on reserve land at the time of sale. This is consistent with provincial sales tax exemption currently provided to First Nations purchasers in British Columbia.

The above decision provides clear legal support for the branch's existing administration of the exemption for First Nations purchases under the Provincial Sales Tax Act.

R.2 Purchases from Out-of-Province Reserves (Issued: 2014/04)

When a First Nation individual or band purchases TPP located on a Canadian reserve at the time of the sale, the TPP qualifies for exemption from tax when brought into British Columbia for the use of the First Nation individual provided that the paramount location of the TPP will be on First Nation land. For vehicles, this means the vehicle will be registered by a First Nation individual or band to an address on First Nation land.

TPP purchased on reserve land in the United States does not qualify for exemption when brought into the province for use. The definition of reserve in the Indian Act (Canada) does not extend to reserves located in the United States.

R.3 Purchases by First Nation Trusts (Issued: 2014/04)

Band-empowered entities, such as a trust operated by an Indian band, do not qualify as First Nation individuals or bands as defined in the Indian Act (Canada) and are, therefore, not eligible for exemption from tax. Purchases by such organizations are subject to tax even if they are located on First Nation land and the sale takes place on First Nation land. The only exception is with respect to purchases of legal services as outlined in PSTERR section 81 [legal services provided to First Nation individuals].

R.4 Purchases by a Bare Trust for a First Nation Individual or Band (Issued: 2014/04)

Under a bare trust arrangement, the bare trustee is only the registered or title holder of any property, and the real and beneficial owners of that property are the persons or entities on behalf of whom the bare trustee is holding title. The bare trustee has no independent powers, but acts only on the instruction of the beneficial owner. In many cases, the purpose of the arrangement is to facilitate dealing with legal matters.

As discussed in Bulletin PST 314, bands can make exempt purchases through persons acting on their behalf, provided those persons have authorization signed by a band official. Similarly, purchases by a bare trustee acting for a beneficiary that is a First Nation individual or band are not subject to tax if all the following criteria are met:

- The purchaser is a trustee and the beneficiary is a First Nation individual or band,

- The trust agreement establishes a bare trust (i.e., the trustee's only duty is to hold the property and convey it to the beneficiary on demand), and

- The purchase occurs on First Nation land.

However, if the purchaser (i.e. bare trustee) is not a First Nation individual or band, a vendor making such a sale will be required to collect tax. The trustee or the beneficiary that is a First Nation individual or band, depending on the circumstances of the purchase, may then apply to the Ministry for a refund of the tax paid. A refund claim will be subject to verification to ensure that the criteria for exemption are met. Documentation will be required to support the claim.

Where the beneficiaries under the trust agreement are partners, and one or more of the partners are non-First Nation individuals or bands, the exemption would apply on a proportional basis to the First Nation individual's or band's interest.

R.5 School Districts Located on First Nation Land (Issued: 2014/04)

School districts that are located on First Nation land do not qualify for exemption as a First Nation individual or band.

School districts are geographic areas established under the School Act for the purpose of managing the provincial school system. They are managed and administered by elected board members who report to the Minister of Education. Because a school district is not a First Nation individual or band, it is not eligible for the exemption.

Purchases by a school district located on First Nation land are subject to tax unless the goods qualify as exempt school supplies under PSTERR section 13 [school supplies obtained for use of student] or PSTERR section 14 [school supplies obtained by qualifying school, school board or similar authority].

GR.3/R.1-R.2: Improvements To Real Property And Affixed Machinery

R.1 Signs (Issued: 2014/04)

If a sign is sold or leased on a stand-alone basis (i.e., it is not installed by the seller or the seller's subcontractor) it is TPP, and the sale or lease is subject to tax.

When a sign is both sold/leased and installed by the seller or the seller's subcontractor, the tax application depends on whether the sign remains TPP or becomes an improvement to real property. If it remains TPP, tax applies to the charges for both the sale/lease and the installation. If it becomes an improvement to real property, the real property contractor rules apply.

Services to signs (including painting) that are improvements to real property are not subject to tax. Services to signs that are TPP are related services and are taxable.

If a sign that is an improvement to real property is removed from the site at which it is affixed or installed, it becomes TPP while it is removed from that site. In this case, services provided to the sign while it is off-site are subject to tax because the sign is TPP. However, tax does not apply to the removal and re-installation charges.

Signs that are detached from real property and repaired on-site (i.e. serviced on-site and then re-installed or affixed) remain improvements to real property. Therefore, the services are not subject to tax.

If a leased sign is used in such a way that it becomes an improvement to real property, under section 88 [tax if leased TPP becomes part of real property] of the Act, the sign is deemed to have been sold to the lessee by the lessor, and the lessee must pay tax on the fair market value of the sign.

R.2 Purchasing Inventory for Resale or Installation to Real Property (Issued: 2014/07)

Real property contractors (contractors) supply and affix, or install, goods that become part of real property. Generally, contractors are the users of the goods and are required to pay PST on the purchase.

A person may sell (supply) the same goods without installation on a retail or wholesale basis (dealers). Dealers are not the users of the goods and are not required to pay PST on the purchase. A person may be both a contractor and a dealer (contractor dealers).

A contractor dealer may purchase goods for resale without paying PST even if the goods may be used by the contractor dealer to fulfill a real property contract at a later date. In order to qualify the goods must meet the following criteria:

- The type of good purchased by the contractor dealer is of a type that is both sold by the contractor dealer at retail or wholesale and is provided under the real property contracts of the contractor dealer (the type of good is not purchased by the contractor dealer solely for use in fulfilling real property contracts);

- The goods are in the possession of the contractor dealer and

- are readily available for resale (e.g., on store shelves or in contractor dealer's resale inventory); or

- are for incorporation into goods for resale (e.g., used to make goods that are for resale and for installation to real property); and

- The goods are NOT acquired to fulfill an existing contract for the supply and installation of improvements of real property.

Separate Inventories for "Retail" and "Installation to Real Property"

If a contractor dealer has two separate inventories (resale and for installation), the contractor dealer may only purchase TPP for the resale inventory without paying PST. TPP purchased for installation is taxable unless a specific exemption applies (e.g., the contractor dealer has an exception rule contract with the end customer or the TPP is exempt TPP).

Exempt TPP used to Fulfill a Real Property Contract

TPP taken out of resale inventory for use in fulfilling a real property contract is taxable under section 81 [tax if change in use of property acquired for resale] of the Act. PST is payable on or before the last day of the month after the month in which the person first become a user of the TPP. The contractor dealer becomes a user of the TPP when the TPP is identified by the contractor dealer as being for use in fulfilling a real property contract.

Tax-Paid Goods that are Sold at Retail or Wholesale

Goods that were intended for use in fulfilling a real property contract that are later sold at retail or wholesale, and that are tax-paid, are eligible for a refund of PST paid in error. To substantiate the refund, the dealer contractor must be able to provide proof of payment of PST on the goods and evidence of the collection of PST on the sale of the goods (without installation) or a relevant exemption certificate from a purchaser, or the purchaser's PST registration number.

Assessments

A contractor dealer may be assessed where they fail to pay PST as required or where they fail to levy tax as required.

As a result, a contractor dealer may be assessed if they purchase TPP or remove TPP from their resale inventory for use in fulfilling real property contract and do not pay PST on the TPP as required. Contractor dealers must keep records to substantiate the payment of PST, including payment by self-assessment. If the TPP removed from inventory qualifies for an exemption (e.g., the contract is with the Federal Government) the contractor dealer must keep records to substantiate the exemption. For example, where the TPP is supplied as part of a contract with the Federal Government, there should be records of the specific TPP being supplied under the contract. This may be done as part of the contract or by having both the contract and a relevant exemption certificate (contractor or subcontractor) exemption certificate completed.

Example Scenarios:

1. Goods Sold at Retail as Well as Provided Under a Real Property Contract

Flooring Store - A flooring store sells carpeting, laminate, and hardwood flooring at retail and also provides the option to have a store employee install the flooring. The store also provides the option of supplying and installing tile flooring but tile is not available at retail from the store (for sale without installation). The store may purchase carpeting, laminate, and hardwood flooring for their inventory without paying PST on the purchase, provided that the flooring is not intended for a specific real property contract. However, the store must pay PST on the purchase of tile flooring (unless they are following the exception rule); the tile is not sold at retail or wholesale by the contractor dealer. If the store enters a real property contract in the future and removes some of the hardwood flooring from its inventory to fulfill the contract, PST is payable on the amount of hardwood removed from its inventory.

2. Goods in Possession of a Contractor for Incorporation Into Goods for Resale

Sign Shop - A sign shop manufactures signs and sells the manufactured signs at retail, and also provides the option to have a store employee install the sign so that it is an improvement to real property. The store does not have an inventory of signs; the signs are made on demand. However, the store does have an inventory of materials that become incorporated into the signs during their manufacture. The sign shop may purchase materials that are incorporated into a sign for its inventory exempt of PST. If the materials are incorporated into a sign that is installed as an improvement to real property, PST is payable on the materials removed from its inventory.

3. Goods Not in Possession of a Contractor

Online sales - A tile contractor sells tiles at wholesale to retailers and provides tiles with installation service (under a real property contract). The contractor does not have a storefront. The contractor makes sales of the tiles and sales of tiles with installation services online (e.g., Craigslist). The contractor does have a warehouse to store tile in inventory (a wholesale location). The contractor may purchase tiles without paying PST to place in inventory. The contractor is a contractor dealer. If the contractor provides tiles on demand (does not have a warehouse), the contractor cannot purchase all tiles without paying PST. In this case, the tiles cannot be in the possession of the contractor and readily available for resale. Another party is holding the tiles in inventory for resale. If the tiles are purchased by the contractor from the third party for resale to a retailer (wholesale), they may be purchased without paying PST. If the tiles are purchased by the contractor from the third party to fulfill a real property contract, the purchase is subject to PST.

GR.4/R.1-R.11: Agency

R.1 What is Agency? (Issued: 2020/10)

Agency is a specific type of legal relationship between two persons (an agent and a principal). The key feature of an agency relationship is that one person (i.e. an agent) acts on behalf of another (i.e. a principal) with the capacity to affect the principal's legal position (e.g. the agent can enter into contracts on behalf of the principal).

Determining whether an agency relationship exists between persons can be difficult. However, if the person cannot affect the legal position of the person for whom they are acting, then no agency relationship exists.

In the context of consumption tax, agency relationships generally arise in two situations:

- An agent acts on behalf of a principal with respect to a purchase (e.g. of TPP); and

- An agent acts on behalf of a principal with respect to a sale (e.g. of TPP).

The legal situation of a principal, that principal’s agent, and a third party with whom the agent contracts on behalf of the principal differs according to whether the principal in question is “disclosed” or “undisclosed”.

Disclosed Principal

Disclosed principals are those whose existence (although not necessarily their names) are revealed to the third party by the agent with whom the third party is contracting.

When a principal is disclosed the third party knows that he is not contracting with the agent personally, but with another person through the agent.

In such a situation, a direct contractual relationship is created between the third party and the principal. The principal is a party to the contract. The agent is generally not a party to the contract.

In the context of an agent-facilitated purchase of TPP from a third-party vendor to a disclosed principal, the vendor sells the TPP directly to the principal and the principal buys the TPP directly from the vendor. Although the agent is involved in making the arrangements, the agent is not a party to the contract and does not acquire TPP.

The principal is considered the purchaser and is obligated to pay the tax. The person who is considered to have paid the tax is the principal.

Undisclosed Principal

Where a principal is undisclosed, neither the identity of the principal nor the fact that the agent is acting on behalf of someone else is revealed to the third party with whom the agent contracts. In such instances, the third party believes that he is contracting personally with the agent.

In this case, the agent is the person contracting with the vendor and is the person who acquires the goods. However, in such a situation, the agent may only acquire legal title to the goods while the principal acquires the beneficial interest in the goods.

In an undisclosed principle scenario both the agent and the principle are considered purchasers of the goods. The agent, principal or both (individually and separately liable) are obligated to pay the tax. However, the agent is considered to have paid the tax.

R.2 Indicators of Agency (Issued: 2014/10, Revised 2020/10)

In determining whether an agency relationship exists, the Ministry will look at the entire transaction and conduct of parties including the following elements:

1. Is there an express written agency agreement?

Although not necessary to create an agency relationship, if there is an agency agreement between the parties the Ministry will generally accept it as evidence of an agency relationship. However, staff should be cautious when reviewing an agreement. Merely naming an "Agency Agreement", is insufficient to establish the agency relationship; the substance of the agreement must indicate an agency relationship.

Agency requires consent by both parties. Consent can be implied by the conduct of the parties or can be an express declaration. A signed declaration by only one of the parties that the other is an agent is not, by itself, conclusive evidence that an agency relationship exists.

2. Who is assuming the risk with respect to the transaction?

Generally, if an agency relationship exists, an agent does not bear risk of loss for property acquired under a contract for which they act on behalf of a principal. The principal is typically the one who bears the risk. Insurance and shipping documents for TPP can aid in determining who bears the risk.

3. Does the purported agent separate funds?

Generally, an agent separates the funds they receive or the expenses incurred from their own funds and expenses.

4. Is the person paid a fee for acting on behalf of another?

An agent will often be paid a fee for acting as agent. An agent's fee should be distinguished from a fee for the purchase of TPP or related services.

5. Who obtains title to any TPP transferred as part of the transaction?

An agent generally does not obtain title to the TPP. Rather, title to the TPP passes directly to the principal. However, there could be some situations where the principal provides the agent with authority to hold title to the TPP.

6. What degree of control exists between the parties?

Typically, a principal exercises a greater degree of control over the actions of the agent than a person would in a contract for goods or services.

For example, an independent contractor acts within the scope of the contract for services and may not be under any control except to provide the goods or services for which the parties contracted.

However, significant control does not necessarily mean an agency relationship exists. For example, an employee/employer relationship often has significant degree of control, but most employees are not agents of their employer (although they can be).

7. Is there an agency relationship by virtue of a statutory rule?

For example, the Partnership Act states that a partner is an agent of the firm and the other partners for the purpose of the business of the partnership.

Ultimately, the law of agency is governed by complex common law rules. If you are unclear as to the nature of the relationship, please contact the Policy, Rulings and Services, Consumer Taxation Programs Branch for a ruling.

R.3 Who can apply for a refund? (Issued: 2014/10, Revised: 2015/02, Revised: 2020/10)

The definition of "purchaser" in section 1 of the Act specifies that when a person acquires TPP at a sale for use or consumption by a principal for whom the person acts as agent, that person (the agent) is a purchaser. The definition of purchaser also contains similar provisions relating to software and taxable services.

The refund provisions in the Act (and regulations) generally state that they apply to the purchaser, or to the person who paid the tax on a purchase - who will generally be the purchaser (agent). The fact that the consideration (e.g., cash) paid to the seller by the agent may be provided to the agent by the principal, or that the agent may be reimbursed by the principal, does not change the fact that the agent is the one who is statutorily required to pay the tax to the seller as a "purchaser." This includes cases where a credit card that has only the agent's name on it is used for payment.

Disclosed Principal

The principal can claim a refund because the principal is considered the person who paid the tax.

Undisclosed Principal

The agent can claim a refund because the agent is considered the person who paid the tax.

R.4 Entitlement to Principal's Exemption (Issued: 2014/10, Revised: 2020/10)

When an agent makes a purchase on behalf of a principal, and the principal is entitled to an exemption/refund, the entitlement to the exemption/refund generally applies in relation to the purchase regardless of the fact that the purchase is being made through an agent.

Disclosed Principal

The principal is exempt based on their own status.

Undisclosed Principal

The agent is exempt based on the principal’s status. The agent can provide the seller with a certificate of exemption filled out in their own name and include the principal’s PST number but still not disclose the agent/principal relationship to the seller. Alternatively, the agent is entitled to a refund from the Ministry under Section 153 based on the principal’s exemption status. At the time when the agent made the purchase on behalf of the principal the agent was exempt based on the principal’s status but did not provide evidence of the qualifying exemption at time of purchase. The agent is still eligible for the principal’s exemption despite the relationship being undisclosed to the seller and qualifies for a refund of the PST paid.

Examples include an agent that purchases goods for a principal who will resell the goods - the goods may be purchased exempt if the agent provides the principal's PST number or completed Certificate of Exemption - General (form FIN 490) (as applicable); or an agent that purchases eligible PM&E for a principal who is a qualifying manufacturer - the PM&E may be purchased exempt if the agent provides a completed Certificate of Exemption - Production Machinery and Equipment (form FIN 492). Please see Bulletin PST 314 for information on requirements relating to purchases made on behalf of a First Nation band.

R.5 Entitlement to Agent's Exemption (Issued: 2014/10, Revised: 2020/10)

When an agent makes a purchase on behalf of a principal in circumstances where the agent would qualify for an exemption/refund if making the purchase on their own behalf, the entitlement to the exemption/refund may apply in relation to the purchase in limited cases (since the agent is the purchaser under the Act).

Many of the exemptions under the Act are tied to use - for example, the PM&E exemption for manufacturers applies to eligible PM&E for use in British Columbia primarily and directly in the manufacture of qualifying TPP. Therefore, a manufacturer would not be able to purchase PM&E exempt as agent on behalf of a principal who is not a manufacturer because the PM&E must be for use to manufacture "qualifying TPP" (this definition is tied to the definition of manufacturer in PSTERR section 90).

A First Nations individual (or band) who makes a purchase as agent on behalf of a principal who is not a First Nations individual may qualify for an exemption in certain circumstances. The applicability of the exemption is determined by the wording of the exemption in question.

TPP: The exemption discussed above does not apply to purchases of TPP. The exemption for purchases of TPP by First Nations individuals is found in section 87 of the Indian Act (Canada). This exemption applies to "the personal property of an Indian or a band situated on a reserve". When an agent purchases TPP on behalf of a principal, the agent is the purchaser (because of the definition of purchaser in the Act) but the TPP is the property of the principal. This means that the exemption does not apply when an agent that is a First Nations individual purchases TPP on behalf of a principal that is not a First Nations individual, because the TPP is not the personal property of an Indian or a band.

Software and taxable services: The exemption may apply to purchases by an agent as described above if all of the requirements of the particular exemption are met. These exemptions are provided for under the Act and are not limited in the same way as the exemption under section 87 of the Indian Act (Canada). For example, the exemption for legal services found in PSTERR subparagraph 81(1)(a)(ii) applies to legal services purchased by a First Nations individual or a band if the legal services are performed on First Nations land. This would include a situation where the First Nations individual is an agent purchasing the legal services on behalf of a principal that is not a First Nations individual as long as the legal services are performed on First Nations land (and appropriate documentation is provided).

Other exemptions are more restricted. For example, the exemption for software found in PSTERR section 68.1 requires that the software be purchased for use on or with an electronic device that (i) is owned or leased by the First Nations individual or band that purchased the software, and (ii) is ordinarily situated on First Nations land.

R.6 Who can be assessed for failure to pay tax on the purchase? (Issued: 2020/10)

Disclosed Principal

In the scenario of a disclosed principal the principal is obligated to pay the tax and therefore, the principal is the person who can be assessed PST due. The agent is not a party to the contract, has not purchased the TPP and therefore cannot be assessed for failure to pay tax.

Undisclosed Principal

In the scenario of an undisclosed principal, both the agent, principal or both are obligated to pay the PST. Therefore, in undisclosed principal agency scenario the agent, principal or both (jointly and severally) can be assessed the PST due.

R.7 Who is required to register and levy PST - the agent or the principal? (Issued: 2020/10)

Whether or the not the agent or principal is required to register to collect and remit PST depends on whether the agent or principal meets the definition of “vendor” or meets the qualifications of an out-of-province business that is required to register as outlined in section 172 and 172.1 of the PSTA.

If only one party, agent or principal, meets the definition of “vendor” or meets the qualifications as outlined in section 172 or 172.1 of the PSTA, then the party who meets the definition or qualifications must register to collect PST and must levy, collect and remit PST as required.

If both the agent and the principal meet the definition of “vendor” or meet the qualifications as outlined in section 172 or 172.1 of the PSTA, then both the agent and the principal must register to collect as described under section 168 of the PSTA.

When both agent and principal must register both agent and principal have an obligation to levy, collect and remit PST. The obligation to levy, collect and remit PST is satisfied for both agent and principal when either the agent or the principal levies, collects and remits PST as required. In terms of registration, both must file returns but where one levies, collects and remits the tax, the other party may file a nil return.

Given filing two returns is not ideal, an optional election is available. In the situation where both agent and principal have an obligation to levy, collect and remit PST they can agree to designate a collector, as per section 179.1 of the PSTA. The agent and principal jointly designate one of them to have the obligation to levy, collect and remit the PST as required. To designate a collector the agent and the principal must both file with the director a designation form. To be eligible, the designate must be registered or be registered by a prescribed date. Once the designation is complete, the designate is obligated to levy, collect and remit the PST. The other party is not required to be registered or required to levy, collect or remit the tax. However, if the designated party fails to correctly levy or remit the tax, the parties are joint and severally liable for the failure.

If an agent is acting as an auctioneer and that agent sells at auction on behalf of the principal, the sale is deemed to be made by the agent and therefore, the obligation to levy and remit PST falls with the agent as the collector. The principal no longer has an obligation to levy and remit PST. There is no need to designate a collector as described above in this scenario. However, the auctioneer (agent) and the principal may choose to make an election modifying the deeming rule (under section 179.2(2)).

R.8 Who can be assessed and penalized for the failure to levy and remit the PST on a sale? (Issued 2020/10)

Where only one of the agent or principal is registered or required to be registered (i.e. only one is a collector), the party that is the collector may be assessed under section 199(2) for failure to remit tax levied. The other party may not be assessed under this provision because they, presumably, did not levy tax. If the collector fails to levy the tax, then only the collector may be penalized under section 203(1) because they are a “collector” while the party that is not registered or required to be registered is not a “collector” as that word is defined in section 1.

Where the agent and principal have not made a section 179.1 election and both are required to be registered (i.e. they are both collectors) and neither party levied, collected or remitted the tax, then the director may assess either one or both under section 199 or 203 for failure to remit or levy tax. In the case where only one levies, collects and remits the tax and the other party files a nil return, the party that did not levy the tax is not liable under section 199(2) because that provision only applies to a person who levied tax (and then did not remit it). The party that did not levy and remit the tax is liable under section 203(1). However, where the other party correctly levied and remitted, the director will generally exercise her discretion under section 203(1.01) to reduce the section 203(1) penalty to zero because the person liable to pay the tax (i.e. the purchaser) paid the tax to government through the other party who levied and remitted the tax. If both the agent and principal are penalized under section 203(1) and one party pays the penalty, the liability of the other party is satisfied through operation of section 203(2).

Where both the agent and the principal are required to be registered but the parties make an election under section 179.1, only the designated collector is required to levy, collect and remit that tax. However, an election under section 179.1 does not absolve the non-designated collector from liability respecting any failure to levy and remit the tax. Under section 179.1(8)(b), despite an election, both the agent and principal are joint and severally liable for an assessment, penalty or interest under section 198, 199, 203, 205, 206 and 206.1.

R.9 Rebillers (Issued: 2014/10, Revised: 2014/11, Revised: 2020/10)

The general rule is that if a person purchases TPP, software, or a telecommunication service and then transfers the TPP, software, or telecommunication service to another person for consideration, then the first person has resold the TPP, software, or telecommunication service to the second person.

However, in some situations a person may claim they are merely acting as a "rebiller" rather than a reseller. For example, a shopping mall may argue that they are rebilling their tenants for electricity rather than reselling electricity. Rather, they purchase the electricity, pay PST to the utility company and then bill the tenants on a cost recovery basis. The mall may make such an argument so that they do not have to register and collect PST.

"Rebilling" is not a concept that is contemplated by the PSTA. However, agency is contemplated by the PSTA (and the common law more generally).

If the "rebiller" establishes that an agency relationship exists between themselves and the person they are rebilling, then the normal rules of agency will apply (see PSTA/GR.4).

In the absence of any agency relationship, the "rebiller" is considered a reseller and must register and collect PST.

Simply because the amount is not marked up is not (in itself) conclusive evidence of an agency relationship. Many businesses sell goods or services at or below cost (e.g., loss leaders or liquidation inventory).

Although not determinative, if the person "rebills" the user of the goods or services at a marked-up price, then it is unlikely an agency relationship exists and the person is generally considered a reseller.

For additional information on determining an agency relationship, see PSTA/GR.4/R.2)

R.10 Billing Agents (Issued: 2014/10; Revised: 2015/09, Revised: 2020/10)

A billing agent generally describes an agent that a collector engages to issue invoices and collect payment (including the PST if applicable) on the collector's behalf after the collector has entered into the sales contract.

In such cases, a billing agent is generally not liable for collection obligation under the PSTA because the billing agent has not sold or provided TPP within the meaning of section 179(1) (unlike a sales agent). Therefore, the ministry generally would pursue the principal rather than the billing agent if tax was not levied, collected and remitted correctly. However, if the tax were collected but not remitted the billing agent may be in non-compliance with the requirements of section 184.

R.11 Agency and Related Individuals (Issued: 2014/10, Revised: 2014/11, Revised: 2020/10)

Merely because two people are related (e.g., husband and wife) does not necessarily mean one is an agent of the other. While related individuals can be agents of one another, to determine if there is an agency relationship consideration must be given to the factors that indicate an agency relationship as set out in PSTA/GR.4/R.2.

GR.5/R.1: Joint Ventures

R.1 Joint Ventures (Issued: 2014/11)

The legal status of a joint venture depends on how the joint venture is structured. A joint venture can be carried out in corporate, partnership, or contractual form.

A corporate joint venture is a corporation like any other. Accordingly, the Ministry deals with the entity as it would any other corporate entity.

In the case of non-corporate joint ventures, the Ministry will treat the joint venture as a joint venture partnership. A joint venture partnership is like any other partnership and is treated as such for tax purposes.

In rare cases, a taxpayer may claim their non-corporate joint venture is a contractual joint venture. In such cases, the issue should be referred to the Program Services section.

GR.6/R.1: Health Authorities

R.1 Health Authorities (Issued: 2015/06)

Under section 15(3) the Health Authorities Act, a health authority is exempt from PST for transactions undertaken for the purposes of the Health Authorities Act between the health authority and a public body or a health authority.

For the purposes of the Health Authorities Act, a "public body" is

- a local government acting under the Public Health Act,

- a hospital as defined by section 1 of the Hospital Act,

- a board, a regional hospital district board, a district, a regional hospital district, a municipal regional board or a regional board as defined by section 1 of the Hospital District Act,

- a Provincial mental health facility, a psychiatric unit or a society as defined by section 1 of the Mental Health Act or a mental health clinic or mental health service established by regulations under section 43 of the Mental Health Act,

- the Council of the city, and the city, under the Vancouver Charter,

- a government corporation as defined in section 1 of the Financial Administration Act, the minister or the government, or

- a designated corporation.

GR.7/R.1-R.2: Consideration

R.1 Accounting Entries as Consideration (Issued: 2016/06)

When there is a purchase or lease of goods with no invoice, sales agreement, lease agreement or any other documentation showing a sale or a right to use goods, it may be difficult to determine the amount of consideration paid.

Corresponding accounting entries (i.e. one company creates an inter-company payable in their books and the other company creates an inter-company receivable) is the equivalent of the payment of money for tax purposes.

The corresponding journal entries support that there is an amount paid or payable for the purchase or lease of goods. The amount accepted by the seller or lessor is the amount recorded in their accounts.

If corresponding journal entries do not reflect fair market value in a non-arm's length transaction, the director may determine the fair market value of the purchase or lease and, pursuant to section 27, this fair market value will be deemed to be the purchase or lease price of the property.

R.2 Fundraising (Issued: 2016/10)

Tangible personal property, software, taxable services, and accommodation are frequently sold within a fundraising context.

If a person pays more than a nominal amount in exchange for TPP, software, a taxable service, or accommodation, a sale has occurred regardless of whether the transaction was characterized as a fundraiser or the item sold characterized as a "reward."

Conversely, it may be assumed that a sale has not occurred in cases where money or something of value is provided by one party (the transferor) to another with no expectation that the transferor will receive something of value in return.

Donative Intent

Donative intent is the intention to provide a gift. In some cases, a person who obtains an item through a fundraiser may have both donative intent and an intention to obtain the item; in other cases, they may only be motivated by their intention to obtain the item.

Generally, the ministry assumes that a person who obtains an item through a fundraiser:

a) May have donative intent if the fundraiser is staged for a charitable purpose;

b) Does not have donative intent if the fundraiser is staged for a purpose other than a charitable purpose (e.g., if the fundraiser is staged to benefit a business).

General Assumption Regarding Purchase Price

Generally, the purchase price of an item purchased in any kind of fundraising context is the full amount of the money or other consideration provided to the seller of the item, even if the amount appears to be higher than expected.

There are two categories of exceptions to this assumption:

Category 1: Fundraiser is staged for a charitable purpose

If a fundraiser is staged for a charitable purpose, it may be assumed that the purchaser of the item intended to (a) purchase the item, and (b) provide a gift. However, this is not necessarily the case: it is also possible that a purchaser did not have donative intent and only paid an amount to purchase the item.

To reduce the subjectivity inherent in making an appropriate assumption regarding donative intent, the organizer of a charitable fundraiser may make a reasonable determination of the value of an item sold to a purchaser and:

a) If the value of the item is 80% or more of the amount provided by the purchaser, the general assumption regarding purchase price applies: the purchase price of the item is the full amount provided by the purchaser.

b) If the value of the item is less than 80% of the amount provided by the purchaser, the purchaser may be assumed to have donative intent: PST may be calculated on the value of the item as determined by the organizer of the charitable fundraiser. Note, however, that the organizer's valuation must be reasonable: the director ultimately remains authorized to determine the purchase price of the item under section 27.

e.g. 1: At a charity auction, a bidder pays $500 for a hockey jersey which the charity reasonably determines to be worth $150. In this case, the charity can assume that the purchaser had donative intent and may collect the PST on the $150 value of the jersey.

e.g. 2: At a charity auction, a bidder pays $1,000 for a diamond ring which the charity reasonably determines to be worth $800. In this case, because the value of the ring is 80% of the successful bid, the charity should not assume that the purchaser had donative intent and should collect the PST on the $1,000 paid for the ring.

Category 2: Clear donative intent

In very limited circumstances, a purchaser may be assumed to have donative intent when they obtain an item in a fundraiser staged for a purpose other than a charitable purpose. For this assumption to be valid, the circumstances must clearly demonstrate that the purchase is separate from the gift.

This assumption may be made if the purchaser, at the time the purchase is made, has the opportunity to buy the same item from the same seller for a price lower than the amount paid in the fundraiser. In such a circumstance, PST may be calculated on the lower price, with the difference between that price and the amount paid by the purchaser treated as a gift.

e.g. 3: A record label releases an album in a digital format. In its online store, the album download is priced at $9.99, but purchasers are given the option of contributing an additional amount to support the musicians who made the album. A purchaser who makes an additional contribution will receive precisely the same digital album as a purchaser who pays the $9.99 price. The purchaser has no expectation of receiving anything of value in exchange for the additional contribution: for instance, they will not receive additional songs or alternate versions of the songs. In these circumstances, a purchaser who contributes an additional amount may be assumed to have donative intent. PST may be calculated on the $9.99 price, with the additional contribution regarded as a gift.

e.g. 4: A video game developer launches a crowdsourcing campaign to fund the development and release of a new game. At the $30 contribution level, the purchaser is rewarded with a limited-edition mouse pad evidencing their participation in the fundraising campaign. This particular mouse pad is not available for purchase outside the campaign. While similar mouse pads may be purchased for far less than $30, the general assumption regarding purchase price applies. Donative intent may not be assumed because the only way to obtain the mouse pad is to pay $30 through the crowdsourcing campaign. PST should be calculated on the $30 paid for the mouse pad.

GR.9/R.1: Post-Production Services

R.1 Application of PST to Post-Production Services (Issued: 2014/07)

Post-production is part of filmmaking, video production and photography processes. It occurs in the making of motion pictures, television programs, radio programs, advertising, audio recordings, photography, and digital art. It is a term for all stages of production occurring after the actual end of shooting and/or recording the completed material.

Generally, when the output of post-production services is a video or audio recording, the post-production services are subject to PST. When provided electronically (e.g., downloaded or streamed over the Internet), the purchase is subject to PST as a telecommunication service under section 130 [tax on telecommunication service] of the Act when downloaded, viewed or accessed by means of an electronic device ordinarily situated in BC. When provided in the form of TPP (e.g., CD, DVD or thumb drive), the purchase is subject to PST under section 37 [tax on purchase] of the Act when purchased at a sale in BC.

The following list describes how PST applies to post-production services provided to video and audio recordings or files. Note that this does not include post production services to digital images such as photographs and artwork.

1. Post-production services provided to TPP, such as physically editing video tape, are subject to PST under section 119 [tax on purchase of related service provided in British Columbia] of the Act.

2. Post-production services to a digital or electronic file are not subject to PST as a stand-alone service. However, this is unlikely to occur as the person purchasing the post-production services will likely want to obtain a copy of the edited file, either electronically or as TPP, from the service provider.

3. Tangible medium and single price - When post-production services are provided and the resulting digital or electronic file is provided to the customer on a tangible medium (e.g. a disc or hard drive) and there is a single price for the service and the tangible good, the entire purchase price is subject to PST for the following reasons:

- Except in the case of a master recording described in PSTR paragraph 7(2)(e) [sale - incidental provision of tangible personal property], the TPP is not considered merely incidental to the provision of the non-taxable post-production service.

- It is not a bundled purchase (section 26 [purchase price if bundled purchase] of the Act), but a single item of commerce in the form of an edited video or audio recording.

4. Tangible medium and separate price - When post-production services are provided and the resulting digital or electronic file is provided to the customer on a tangible medium (e.g. a disc or hard drive) and there are separate prices for the post-production service and the tangible medium, the entire purchase price (both the service and the tangible medium) is subject to PST. This is because the customer is purchasing a single item of commerce in the form of an edited video /audio recording on a tangible medium.

5. Digital file and single price - When post-production services are provided and the resulting digital or electronic file is provided electronically (e.g. it is emailed or downloaded from a server) and there is a single price for the post-production service and the telecommunication service, the entire purchase price is subject to PST for the following reasons:

- Except in the case of a master recording described in PSTR paragraph 7(2)(e), the telecommunication service is not merely incidental to the provision of the non-taxable service.

- It is not a bundled purchase, but a single item of commerce in the form of an edited video or audio recording.

6. Digital file and separate prices - When post-production services are provided and the resulting digital or electronic file is provided electronically (e.g. it is emailed or downloaded from a server) and there are separate prices for the post-production service and the telecommunication service, the entire purchase price (both the service and the tangible medium) is subject to PST. This is because they are purchasing a single item of commerce, an edited video provided in the form of a telecommunication service.

7. Customer owned TPP - When post-production services are provided and the resulting digital or electronic file is provided to the customer on the customer's own TPP (e.g. the customer provides a hard drive to the service provider), the entire purchase price is not subject to PST because the purchaser is not purchasing TPP or a telecommunication service.

GR.10/R.1: Refunds

R.1 Exemptions, Refunds and Multiple Lessees (Issued: 2016/06)

Some lease contracts name more than one lessee. Depending on the contract, each person may be referred to as a "lessee" or some may be called "co-lessees." In many cases, a co-lessee may have no intention to use the equipment in their own right, but has agreed to be named as co-lessee at the request of the lessor (who benefits when the lease contract is binding on more than one party).

Where a lease contract names multiple lessees (including when parties referred to as "lessee" and "co-lessee" have the same responsibilities under the contract), each party is responsible for paying consideration and tax. The ministry looks to these shared obligations in determining how exemptions and refunds apply.

If an exemption applies regardless of who obtains tangible personal property, the exemption applies uniformly to a lease contract with multiple lessees. For example, if multiple lessees lease a fleet of bicycles, the lease is completely exempt.

If an exemption depends on who obtains TPP, the exemption is apportioned according to the makeup of the lessees. For example, under a contract with two lessees, if one lessee is a party who would qualify for the exemption and one lessee is a party who would not qualify for the exemption, PST applies to 50% of the lease price.

The exemption is apportioned on the basis of the lease contract, and not according to evidence of who appears to bear the economic burden of the contract. For example, if a lessor collects consideration and tax using pre-authorized debits drawn on a single lessee's bank account, the exemption must still be apportioned according to the number of lessees named in the lease contract. It does not change to recognize the source of the funds.

The same rationale applies to refunds involving lease contracts with multiple lessees. In some cases, each lessee may be entitled to a refund. In other cases, some lessees may be precluded from receiving a refund. This is illustrated in the following examples:

Example 1: Hazardous Chemicals Ltd. ("HCL") manufactures chemicals. All of the employees who work at its manufacturing site are required to wear a self-contained breathing apparatus ("SCBA"). Several dozen SCBAs are needed, and are leased from Safety Supply Ltd. ("SSL"). The lease contract names HCL as "lessee" and the three shareholders of HCL-Doe, Jones, and Smith-as "co-lessees." Under the lease contract, HCL, Doe, Jones, and Smith all have the same responsibilities. SSL charges PST on the monthly lease payments. By issuing cheques drawn on its bank account, HCL provides 100% of the funds to pay the consideration and tax shown on SSL's invoices.

PSTERR paragraph 32(1)(b) provides an unconditional exemption for certain respirators, including SCBAs, designed to be worn by a worker. Because the exemption does not require that the SCBAs be obtained by a specific person (e.g., a manufacturer or an employer), HCL, Doe, Jones, and Smith may all file separate refund claims. If the director confirms that PST has been paid, each claimant will receive a 25% share of the PST paid to SSL. The four-way apportionment of the PST burden is made on the basis that four lessees are party to the contract. Evidence that HCL may bear the economic burden for the lease (by issuing cheques to SSL) does not impact the apportionment of the refund. The assignment of a refund entitlement is not permitted under the Act. Therefore, each lessee must file a claim if the PST is to be fully refunded.

Example 2: HCL uses a large chiller in its chemical manufacturing operation. The chiller is leased from Industrial Equipment Ltd. ("IEL"). The lease contract names HCL as "lessee" and the three shareholders of HCL-Doe, Jones, and Smith-as "co-lessees." Under the lease contract, HCL, Doe, Jones, and Smith all have the same responsibilities. IEL charges PST on the monthly lease payments. By issuing cheques drawn on its bank account, HCL provides 100% of the funds to pay the consideration and tax shown on IEL's invoices.

PSTERR section 92 provides an exemption for machinery or equipment obtained by a manufacturer for use primarily and directly in the manufacture of qualifying tangible personal property. HCL is a manufacturer, and the chemicals it manufactures are qualifying TPP. The chiller is used by HCL primarily and directly in its chemical manufacturing process. HCL may file a refund claim on account of this exemption. If the director confirms that PST has been paid, HCL will receive a 25% share of the PST paid to IEL. The four-way apportionment of the PST is made on the basis that four lessees are party to the contract. Evidence that HCL may bear the economic burden for the lease (by issuing cheques to IEL) does not impact the apportionment of the refund. Any refund claim by Doe, Jones, or Smith will not succeed because they do not qualify for the PSTERR section 92 exemption in their own right (as the manufacturer, HCL is the only party that qualifies for the exemption).

GR.11/R.1: Non-Taxable Items

R.1 Tax Exempt Items vs. Items Not Subject to Tax (Issued: 2016/06)

The Act distinguishes between items exempt from tax and items which are not subject to tax at all (i.e. non-taxable). For practical purposes, tax is not imposed on either category of items. However, there are provisions in the Act where this distinction is made. An example is the definition of "non-taxable component" in section 1 of the Act: property, software or a service that, if purchased separately from a taxable component, would not be subject to tax under this Act or would be exempt from tax under this Act.

Tax exempt items are those ordinarily subject to tax under the general taxing provisions, but are exempted from tax by a specific provision in the Act. For example, plants and animals which are ordinarily food for human consumption are tangible personal property. Ordinarily, a purchaser of tangible personal property for use in British Columbia is required to pay or self-assess tax on that purchase under the Act. However, the Act then provides a specific exemption on animals or plants constituting food for human consumption. The purchaser is no longer required to pay or self-assess tax on their food purchase.

Items not subject to tax are those which are not captured by any taxing provision in the Act. For example, most intangible property (with the exception of software) is not subject to tax. No exemption is necessary to buy or sell most intangible property without tax under the Act.

Where the Act refers to items exempt from tax, this does not include items not subject to tax. For example, collectors can be required to obtain documentation of their customer's entitlement to an exemption in order to avoid penalties imposed under the Act. Collectors are not required to obtain such documentation when they sell items not subject to tax.

In some cases, the Act refers generally to "property" or "services" with no other qualifiers. For example, a person who makes Canadian sales of more than $1.5 million per year in either property or services must file and remit tax returns electronically. This figure would include all types of property or services, whether tangible or intangible, exempt, taxable, or non-taxable.

GR.12/R.1: Sales To Government

R.1 Sales to other Provincial Governments (Issued: 2017/05)

Under Section 125 of the Constitution Act, 1867 (Canada), provinces are exempt from paying other provinces' taxes. For example, if another provincial government brings goods into British Columbia for use, it is not required to pay the PST.

GR.13/R.1: Nontaxable Service Provided Online

R.1 Nontaxable service provided via the internet along with software or a telecommunication service (Issued: 2020/07)

PST does not apply to an amount charged for a nontaxable service provided on its own or for a nontaxable service provided with one or more other items none of which is subject to PST. PST can apply to an amount charged for a nontaxable service provided with something that is subject to PST, such as software or a telecommunication service.

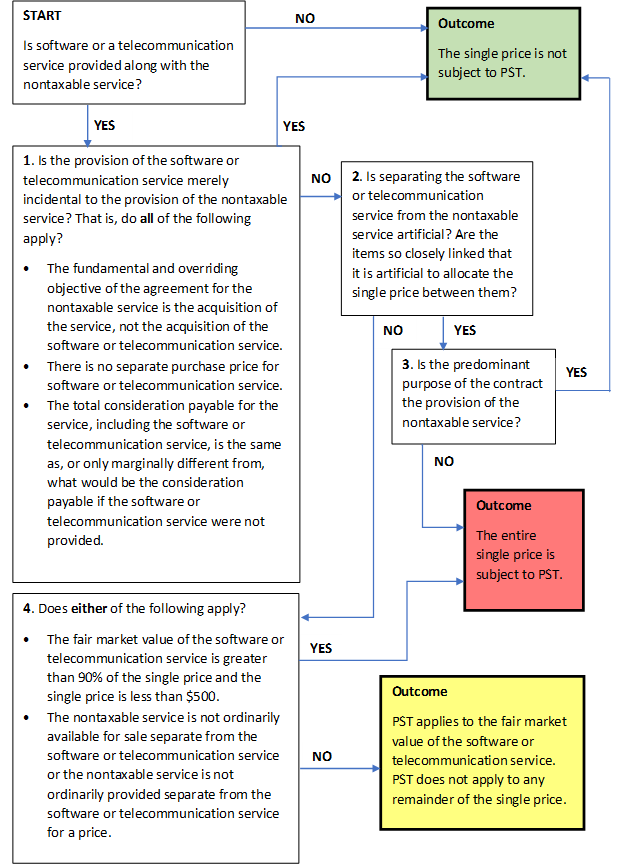

The following flowchart describes the general process of applying PST to a single price, or to part of the single price, charged for a nontaxable service provided via the internet under an agreement that allows use of software or a telecommunication service in relation to the nontaxable service. In this case, the answer to the starting question is “yes”. Assume the software or telecommunication service would be taxable when provided on its own.

- Is the provision of the software or telecommunication service merely incidental to the provision of the nontaxable service?

Sale excludes the provision of software or a telecommunication service that, in prescribed circumstances, is merely incidental to an agreement for the provision of a nontaxable service. PSTR section 7 [Sale – incidental provision of tangible personal property] prescribes those circumstances, the most generally applicable of which are the following:

- The fundamental and overriding objective of the agreement for the nontaxable service is the acquisition of the service, not the acquisition of the software or telecommunication service.

- There is no separate purchase price for the software or telecommunication service.

- The total consideration payable for the service, including the software or telecommunication service, is the same as, or only marginally different from, what would be the consideration payable if the software or telecommunication service were not provided.

If all of the circumstances above apply, there is no sale of the software or telecommunication service. The single price is not subject to PST. The remaining steps can be ignored.

If at least one of the circumstances above does not apply, there may be a sale of the software or telecommunication service. If there is, all or part of the single price can be subject to PST. The next step (step 2) is to determine, based on the facts of the case, which of the following applies:

- There is a sale of a nontaxable service only;

- There is a sale of software or a telecommunication service only; or

- There is a bundled sale of a nontaxable service and software or a telecommunication service.

- Is separating the software or telecommunication service from the nontaxable service artificial? Are the items so closely linked that it is artificial to allocate the single price between them?

PST can apply to the entire price charged for a good made of something normally taxable and something normally exempt. For example, a vodka-and-juice beverage ordered in a bar is fully taxable even if its main ingredient by volume (the juice) would be exempt on its own. The vodka and the juice comprise a single good that is liquor. Even if the bar were to supply the vodka and the juice separately for the patron to mix, it would be artificial to treat the vodka and the juice as separately purchased goods and apply PST to the vodka only. Similarly, the nontaxable help desk service in example 3 (below) is dedicated to the payroll software and is therefore so closely connected to supplying that software that allocating the single price between the service and the software would be artificial.

This step involves determining whether or not it is artificial to allocate the single price between the nontaxable service and the software or telecommunication service. It leads to either step 3 or step 4. Step 4 does not follow step 3.

If it is artificial to allocate the single price between the nontaxable service and the software or telecommunication service, a single item is being sold. The single price should be treated as the purchase price of the nontaxable service or the purchase price of the software or telecommunication service. The next step (step 3) is to determine the predominant purpose of the agreement under which the nontaxable service and the software or telecommunication service are provided.

If it is not artificial to allocate the single price between the nontaxable service and the software or telecommunication service, more than one item is being sold. There is a bundled sale of a nontaxable component (the nontaxable service) and a taxable component (the software or telecommunication service). The next step (step 4) is to determine whether to apply PST to all of the single price or to apply PST to part of it.

- Is the predominant purpose of the agreement the provision of the nontaxable service?

If a single item is being sold and the predominant purpose of the agreement is the provision of the nontaxable service, the single price forms the purchase price of a nontaxable service. It is not subject to PST.

If a single item is being sold and the predominant purpose of the agreement is the provision of the software or telecommunication service, the entire single price is subject to PST as the purchase price of software or a telecommunication service.

- Does either of the following apply?

- The fair market value of the software or telecommunication service is greater than 90% of the single price and the single price is less than $500.

- The nontaxable service is not ordinarily available for sale separate from the software or telecommunication service or the nontaxable service is not ordinarily provided separate from the software or telecommunication service for a price.

This step involves using PSTA subsection 26(4) [Purchase price if bundled purchase] to determine whether or not the purchase price of the taxable component equals the entire single price. If neither condition under subsection 26(4) applies, the purchase price equals the fair market value of the software or telecommunication service, under subsection 26(3).

If either condition above applies, the purchase price of the taxable component (the software or telecommunication service) equals the entire single price. The entire single price is subject to PST.

If neither condition applies and the taxable component is the telecommunication service, the purchase price of the taxable component equals the fair market value of the telecommunication service. PST applies to that fair market value. Any remainder of the single price is not subject to PST.

If neither condition applies and the taxable component is the software, the purchase price of the taxable component equals the fair market value of the software. That purchase price is subject to PST unless the exemption available under PSTA section 137 [Taxable component sold with non-taxable component for single price] applies. Any remainder of the single price is not subject to PST.

The process described above involves a single nontaxable service and a single piece of software or single telecommunication service. It can be followed if the agreement provides for more than two items, such as a nontaxable service and both software and a telecommunication service. Each provision of software or a telecommunication service is evaluated separately. The exemption under section 137 cannot apply to a taxable component if that component, or any other taxable component sold for the single price, is a telecommunication service.

Examples

Example 1

In this example, software and a telecommunication service are merely incidental to a nontaxable accounting service.

- A business in Vancouver hires a service provider in Vancouver to perform the business’s payroll accounting;

- The service provider accepts payroll information submitted in person, via delivery, or via a private area of its website accessible only by the service provider and its clients;

- The business uses the website to log in and out, create employee records, enter each pay period’s payroll data, and download processed payroll data files created by the service provider;

- The service provider charges the business a single price based entirely on the accounting services provided (in this case, periodic payroll and annual T4 processing and accounting) and the number of employees;

- The agreement for the services expressly grants the business the right to use the private area of the service provider’s website;

- The agreement does not expressly grant the right to use software.

Even though the agreement does not expressly grant the right to use a computer program, it provides software by granting the right to use webpage functionality that goes beyond the ability to view webpage content. That functionality requires use of computer programs, which the business accesses and causes to run by means of the service provider’s webpages.

The agreement grants the business the right, whether exercised or not, to use a telecommunication system (the private area of the service provider’s website) to send and receive telecommunications (employee and payroll data) by means of an electronic device ordinarily situated in BC. That right is a telecommunication service for the purposes of PST. The business obtains that right under its agreement with the service provider. It does not obtain that right under its agreement for monthly internet service.

The answer to the start question is “yes”. The next step (step 1) is to determine whether or not there is a sale of a telecommunication service and whether or not there is a sale of software. If the right to use the private area of the service provider’s website and the right to use the computer programs that enable the private area’s webpage functionality are merely incidental to the provision of the accounting service, the service provider is selling only a nontaxable service.

In this case, the business can use the software and the telecommunication service only for sending and receiving data. Because the business receives the same payroll accounting service regardless of how it sends and receives its payroll data, it is reasonable to consider both the software and the telecommunication service as items provided solely for the purpose of facilitating submitting and receiving payroll information, and therefore to consider the fundamental and overriding objective of the agreement for the payroll accounting service to be the acquisition of the accounting service, not the acquisition of the software or the telecommunication service.

There is no separate price for the software or the telecommunication service. And the total consideration payable for the accounting service, including both the software and the telecommunication service, is the same as what would be the consideration payable if neither the software nor the telecommunication service were provided.

The answer to step 1 is “yes”. Therefore, there is no sale of software or a telecommunication service. Both are merely incidental to the provision of a nontaxable service. The single price charged by the service provider forms only the purchase price of the nontaxable service. It is not subject to PST. (Steps 2, 3 and 4 can be ignored.)

Example 2

In this case, there is a sale of software and a telecommunication service, and PST applies to part of the single price.

The facts of the case are the same as example 1’s, except:

- The business opts for the service provider’s deluxe service with webpage functionality that enables the business to run customizable payroll and analytical reports, calculate pay runs and schedule employees, and the business’s employees to update their files and obtain paystubs and T4s online;

- The service provider still charges the business a single price based expressly on the accounting services provided (periodic payroll and annual T4 processing and accounting) and the number of employees but the per-service and per-employee charges have increased by 25%;

- The agreement for the services expressly extends the business’s right to use the private area of the service provider’s website to the business’s employees.

In this case, the business receives the same accounting services. It pays 25% more in order to acquire the right to greater webpage functionality and the right for its employees to telecommunicate with the service provider. The fundamental and overriding purpose of the agreement now includes the acquisition of software and a telecommunication service for purposes other than merely facilitating sending and receiving. And total consideration payable for the service, including the software and the telecommunication service, is more than marginally greater than what would be the consideration payable if the software and the telecommunication service were not provided. The answer to step 1 is “no”. Therefore, there may be a sale of software, a telecommunication service or both.

Because the service provider accepts payroll information not only via a private area of its website but also in person and via delivery, its accounting service does not require the purchase of software or a telecommunication service. By agreeing to pay 25% more in order to acquire the software and the telecommunication service, the business purchases something in addition to the accounting service. It is therefore not artificial to separate the software and the telecommunication service from the nontaxable accounting service. There is a bundled sale of a nontaxable service, software and a telecommunication service. The next step (step 4) is to determine whether PST applies to all or part of the single price. (Step 3 can be ignored.)

Neither condition under step 4 applies: assuming the 25% price increase reflects the fair market value of the deluxe service’s software and telecommunication service, neither the fair market value of the software nor the fair market value of the telecommunication service is greater than 90% of the single price; and the nontaxable accounting service is ordinarily available for sale separate from the software and the telecommunication service. Therefore, PST applies to the fair market value of the software and the fair market value of the telecommunication service. It does not apply to the remainder of the single price.

Example 3

In this case, there is a sale of software and the entire single price can be subject to PST.

- A service provider in Vancouver sells subscriptions for online payroll processing and accounting;

- All subscriptions are identical;

- Each subscriber uses the service provider’s website to create employee records and schedules, enter pay period information and generate payroll accounting, reports and returns;

- Subscribers’ employees use the website to update their records and obtain paystubs, records of employment and T4 slips;

- Subscribers and employees send and receive payroll information electronically only, via the private area of the service provider’s website accessible only by subscribers, their employees and the service provider;

- The service provider provides a dedicated help desk for all subscribers and their employees;

- Each subscriber pays a single price each month, based on the number of employees paid in the month.

The answer under step 1 is “no” because the fundamental and overriding objective of the agreement includes the acquisition of software the subscriber must use in order to obtain the services provided. The services require extensive use of webpage functionality that goes beyond the ability to view webpage content and is created by computer programs accessed via the service provider’s webpages.

Each subscription is a sale of software, which the subscriber purchases for use via a client-server arrangement rather than for use solely on the subscriber’s own hardware. The only nontaxable service the subscriber obtains is the help desk service. Because that service is dedicated to use of the software, separating the service from the software is artificial (step 2). Because the predominant purpose of the agreement (step 3) is the provision of the software, not the provision of the help desk service, the entire single price forms the purchase price of software. It is subject to PST if the software is obtained for use on or with an electronic device ordinarily situated in B.C.

GR.14/R.1: Parts Policy Framework

R.1 Parts policy (Issued: 2023/09)

The following framework describes the treatment of parts, materials, and accessories under the Provincial Sales Tax Act (PSTA).

Part