3.3 Wildlife trees

Learner outcomes

On completion this wildlife tree component, you will understand the role that the stand level component — wildlife trees — plays in forest biodiversity and you will be able to

- Describe wildlife trees

- Describe the role of wildlife trees in biodiversity

- Identify forest management applications for wildlife trees

What is a wildlife tree?

Wildlife tree means a tree or group of trees that are identified to provide present or future wildlife habitat.

A wildlife tree is any standing dead or live tree with special characteristics that provide valuable habitat for the conservation or enhancement of wildlife. Trees in various stages of life, death, and decay are important components of the structure and function of all natural forest ecosystems. Wildlife trees are part of this cycle of life and death. They are constantly being formed by biotic and abiotic factors such as insects, fungi, fire, and weather.

Interactions between wildlife and trees

It takes decades, even centuries, for a tree to complete the cycle of germination, maturation, and decay. Careful assessment and conservation of wildlife trees during harvesting and silviculture operations help to ensure continued existence of wildlife tress in managed forests.

Rapid death by fire produces a different kind of wildlife tree than gradual death by insects or disease. Wildlife trees are created or caused by influences such as animal excavations, disease, insect attacks, wind, snow, and lightning. Insects and disease create most of the wildlife trees in the forest. Local climate and tree species also influence the way a tree deteriorates and decays.

List several ways that wildlife trees are a valuable habitat.

There are many habitat characteristics associated with wildlife trees. More than 80 species of vertebrates and countless invertebrates depend on these habitat features for part of their livelihood. The value of any particular tree as wildlife habitat depends on a variety of attributes, including structure, age, condition, abundance, species, geographic location, and surrounding habitat characteristics. When considering the needs of wildlife, it is important to recognize that all trees are not equal in value. Some of the most significant indicators of wildlife tree quality are:

- Height and diameter

- Decay stage

- Location

No one wildlife tree management approach is suitable on all sites. Factors, such as stand type and condition, tree species, and windthrow hazard, create unique conditions for each stand. The consideration of long-term stand and tree dynamics (i.e., longevity, decay type and rate etc.) that impact the biodiversity value of individual trees and groups of trees left after harvest is critical. A strategy that incorporates a diversity of approaches to stand-level retention is often the most effective.

Characteristics of wildlife trees

One or more of the following characteristics may determine if a wildlife tree is a valuable habitat:

- Large size (diameter and height-greater than 15 metres in height preferable; greater than 30 cm dbh preferable (interior); and greater than 70 cm dbh preferable (coastal)

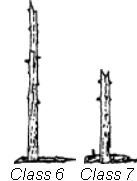

- Condition and age (decay stage, see Figure 8, left)

- Wildlife tree class — tree classes 2-6 most valuable

- Location and surrounding habitat features

- Windfirm

- Sound root system

- Broken top

- Some large branches

- Abundance and distribution

- Cause of tree mortality

- Evidence of wildlife use (feeding, nesting, roosting or denning)

What organisms inhabit wildlife trees? How do these organisms use wild life trees?

Large, live trees provide:

- A future source of standing dead trees and coarse woody debris

- Foraging sites for many insectivorous birds (woodpeckers, nuthatches, chickadees)

- Large, well-branched structures for platform nesting birds (eagles, osprey, herons, hawks)

- Broad, deep canopies that intercept snow and modify microclimates

- Substrates for mosses and lichens

- Some intact bark with space behind loose bark

In addition, standing dead trees and dying trees provide:

- Cavities for nests, roosts and dens (especially in trees with extensive heartrot)

- Perching sites

- Foraging sites for insectivorous birds

- In thick barked species (for example, Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine), cracks and fissures, and spaces behind loose bark provide feeding and nesting/roosting opportunities for bats and some birds such as the Brown Creeper

- A source of coarse woody debris

How is being cognizant about the life stages of wildlife trees useful in your work?

Although different animals prefer trees with various characteristics, some trees stand out as being particularly valuable to wildlife. Generally, the following characteristics indicate the relative habitat value of a wildlife tree. (See Figure 8, right).

| High — A high value has a least two of the characteristics listed below and, where possible, is within the upper 10-15% of the diameter range distribution |

|---|

|

| Medium |

|

| Low |

|

| More Information: Wildlife Tree Committee of British Columbia |

Categories of wildlife tree users

In British Columbia, more than 80 animal species depend in some way on wildlife trees. Approximately 18% of all bird species that breed in British Columbia nest in cavities in wildlife trees. These include several rare and endangered species.

Wildlife trees may be used for a variety of purposes, including nesting, perching, feeding, denning, roosting, and expressing territoriality. Wildlife tree users can be divided into five general categories or guilds:

- Primary cavity excavators

- Secondary cavity users

- Open nesters

- Mammals

- Amphibians

Name several rare and endangered species that depend on wildlife trees. Name several examples of each category.

Before reading further, what do you already know about each sub-heading?

The information on wildlife trees is divided into four parts:

- General principles for managing wildlife trees

- Wildlife tree patches

- Individual live tree retention

- Creating wildlife trees

General principles for managing wildlife trees

Wildlife tree requirements can be applied to any silvicultural system. The seven silvicultural systems used in BC are:

- Coppice

- Clearcut

- Patch cut

- Retention

- Seed tree

- Selection

- Shelterwood

Silvicultural systems on most sites have been designed to maximize the production of timber crops. Non-timber objectives, such as avalanche control and wildlife production, have been less common. Recently, ecological considerations and resource objectives have increased.

- More information on sivicultural systems

- Figure 9a Reserves for wildlife trees in silvicultural systems

- Figure 9b More reserves for wildlife trees in silvicultural systems

What is the definition of silvicultural systems?

There are two types of wildlife tree management strategies commonly used in BC:

- Wildlife tree patch retention

- Individual live or dead tree retention

Although both approaches can be applied within a single cutblock, wildlife tree patches are recommended as the priority approach in most cases.

What do you already know about these three strategies?

Wildlife tree patches (WTP)

Wildlife tree patches provide several advantages over other leave strategies.

-

Potentially dangerous trees are more safely retained and operational inconvenience is minimized.

-

There is increasing evidence that patches of trees provide better habitat for wildlife than scattered individual trees. As well, they provide an area of relatively undisturbed forest floor within cutblocks from which fungi, mycorrizie and other organisms can recolonize the site.

In many cases, WTPs can be conveniently

- Located in or adjacent to gullies, rock outcrops, riparian areas, inoperable areas, and other special habitats

- Located in places that pose harvesting, yarding or regeneration problems

- Located on sites which already require special management practices (e.g., riparian management areas)

Why is a group of wildlife trees better than a single tree for birds? Is there other wildlife that would benefit from groups of trees too? (Explain and give examples)

Wildlife tree patch composition

Wildlife tree patches (WTPs) provide several advantages over other leave strategies:

- Potentially dangerous trees can be retained within a no-work zone (the patch).

- In some cases, it is operationally easier to retain trees in patches versus individual stems.

- Patches provide: an area of undisturbed forest floor within cutblocks, stand structural heterogeneity, and vegetation species diversity.

- Patches often provide better habitat for wildlife than scattered individual trees.

- In many cases, WTPs can be located in or adjacent to gullies, rock outcrops, riparian areas, inoperable areas, and other special habitats or locations that are likely to pose harvesting or regeneration problems, or already require special management practices (e.g., riparian management areas). However, to be appropriate wildlife tree patches, these areas must have wildlife tree attributes.

A range of tree diameters should be included within WTPs, favouring larger stems when possible (a recommended range is >30 cm dbh (larger on coast/interior wet belt) and >15 m in height). Care should be taken to include the upper 10% of the diameter distribution of the pre-harvest stand as these are the most valuable wildlife trees. Patches should include both live and dead trees (subject to safety requirements) representing a range of decay classes. In general, class 2 – 6 wildlife trees are most valuable to wildlife over longer periods.

A variety of tree species, including deciduous, should be represented. When possible include trees showing wildlife use (e.g., nest holes, feeding excavations) or characteristics of large size, well-branched structure, and presence of heart rot.

How does this information change or modify what you already knew? Are there other wildlife tree characteristics? List them.

For example, a valuable wildlife tree might exhibit the following characteristics:

- Greater than 15 m in height

- At least 30 cm diameter (greater on coast/interior wetbelt) at breast height for larger species such as woodpeckers, owls or marten

- Broken top or other external defect

- Some intact bark and branches

- Windfirmness

- Minimal lean

- Located near a riparian area, if possible

- Distributed in a clump or patch with a mix of live and dead trees and vegetation species (hardwoods, conifers, shrubs)

Wildlife tree patches can be a range of sizes. They can be a small clumping of several trees or large treed areas covering many hectares. The size of a wildlife tree patch is generally determined by the features to be maintained within the patch and safety considerations (the size of the no work zone). However, larger patches are generally better from a habitat and operational perspective. It is suggested that the interpatch distance requirement be met by wildlife tree patches 0.25 hectares or larger. However, individual wildlife trees play an important habitat role, especially when combined with wildlife tree patches. Where individual wildlife trees are reserved, an appropriate basal area equivalency can be calculated for their contribution to patch retention requirements (to be considered wildlife trees, these trees should be retained for an entire rotation).

Wildlife tree patch distribution — Inter-patch distance

The importance of wildlife tree patches within cutblocks increases with size of the cutblock.

- The overall objective for distribution of wildlife trees is to retain WTPs across the landscape.

- At the stand level, patches should generally be centred around the most suitable trees and be distributed throughout the cutblock — based on available suitable habitat features on the block.

Where operationally feasible, more patches should be left within cutblocks to achieve biodiversity, visual, water quality, or other objectives.

In your experience, have enough patches been left in BC forests? If not, how can this be changed?

Recommendations for wildlife tree patches

There are two recommendations for the area and distribution of wildlife tree patches:

-

Wildlife tree patches can range in size from individual trees to patches of several hectares.

Individual trees with high habitat value (e.g., a raptor nest tree or veteran tree) outside of patches can contribute to the required retention on a basal area equivalency basis. -

Wildlife tree patches are maintained for at least one rotation.

Seed trees planned for removal do not contribute to wildlife retention targets. Generally, wildlife tree patches should not be entered for any level of harvesting. However, if harvesting (or salvage) of selected trees is required to meet safety concerns, or objectives such as forest health this may occur. Where appropriate, trees felled for safety reasons should be left on site for coarse woody debris. Plans should specify acceptable levels of windthrow or other damage beyond which salvage operations should occur. Where salvage does occur, these areas should be replaced with other suitable wildlife tree patches as close to the original patch as practical.

- Do you agree with these two recommendations? If so, why? If not, why not?

- Are there other recommendations that you think should be made? If so, what are they?

Applications to forest management

The ecological value of WTPs can often be enhanced with the retention of single stems throughout the cutblock area. When retaining individual stems, the following should be considered: Figure 8. British Columbia's wildlife tree classification system

- Class 2 live, defective trees (e.g., live tree with a dead top) are important as future habitat since they provide recruitment wildlife trees over time.

- A small no-work zone may be required around some live trees with hazardous features (e.g., large dead limbs) to protect workers.)

- Large, live healthy trees (class 1) within cutblocks (such as veterans) that are reserved can also function as future wildlife trees if retained throughout or across rotations.

- Some dead trees can be left in forest operations without no-work-zones provided they have been assessed as safe.

- Deciduous trees should be retained wherever practical. They can often be a preferred tree for nesting and feeding by some wildlife tree users, and have an added advantage of being less susceptible to windthrow in late autumn and winter when severe windstorms are more common.

- Advanced regeneration can also be left on the block to provide structural diversity.

More information: Wildlife Tree Committee of British Columbia

Individual live tree retention

Individual live tree retention has four subheadings:

- Worker safety issue-wildlife tree retention

- Common safety problems

- Worker safety recommendations

- Recommendations for individual live tree retention

Even though it is the preferred leave strategy, not all blocks can accommodate wildlife tree retention in patches. Depending on site-specific factors (such as topography, wind exposure, stand age and structure, rotation length, silvicultural system and harvesting method) some locations may be better suited to individual tree retention as a wildlife tree management strategy. Individual live trees left as wildlife trees can contribute to the required WTP area retention (see Table 1-A and Table 1-B) on a basal area equivalency basis. However, simple stem basal area does not equate to patch area. (WTP — wildlife tree patches). Basal area equivalency is only about the amount of basal area. The context here is basal area equivalency is the amount of basal area that is dispersed compared to the amount of basal area in an unharvested patch of trees.

Worker safety issue — wildlife tree retention

Regardless of the management objectives or practices, worker safety must always remain a paramount concern. This is especially true for practices involving wildlife tree retention in harvesting operations. Safe work practices must be followed at all times when implementing the recommendations in this workbook.

For the most up-to-date detailed information on safety concerns and the wildlife / danger tree assessment procedure, please go to the following web site: Wildlife Tree Committee of British Columbia.

Forest workers have the freedom to remove obstacles whenever necessary to maintain a safe working environment.

For example, trees that are intended to be retained after harvest such as those within WTPs and riparian reserve zones can be felled for safety reasons.

However, these trees should be left on the ground as future coarse woody debris. This will retain the benefit these trees can have on site and remove any incentives for felling and harvesting.

Worker safety recommendations

Here are five worker safety recommendations:

- Suspect dangerous trees can only be retained during harvesting operations if they are one of the following:

- Assessed as safe for the given level of disturbance (e.g., the work operation which is about to occur)

- Located along the block boundary and are leaning away from or cannot reach the work area

- Surrounded by a live tree buffer of sufficient size and width such that no standing dead trees or any part thereof will reach the work area

- The safest way to retain suspect trees in any silvicultural system application is to locate them within a wildlife tree patch, thereby buffering the work area.

- Standing dead tree height and size of the adjacent green timber will determine the shape and width of the green tree safety buffer (called a no-work zone) that may be required to protect workers during harvesting activities (see Figure 10).

- No worker shall enter a no-work zone (the safety buffer area surrounding a designated wildlife tree) except to remove other specific hazards that can reach the work area.

- Other factors such as slope, wind exposure, type of harvesting and yarding equipment, and the desired silvicultural system must also be considered when planning and designing wildlife tree patches that can function as safe buffer areas around standing dead trees.

- When individual trees (including vets, seed trees, residuals and advance regeneration) are retained in the block where cable yarding is used, caution must be observed that these not interfere with the mainline or haulback.

What other worker safety recommendations can you add to this list? How will these factors influence the planning and designing of patches?

Recommendations for individual live tree retention

Here are some recommendations for the area and distribution of individual live tree retention.

-

The amount of retention to be applied (% of cutblock area required as WTPs) is determined from Table 1-A. This area is based on the proportion of each biogeoclimatic subzone in the landscape unit (LU), watershed, or other similar management unit that is operable, and the degree of development in the subzone that has occurred prior to application of these recommendations.

-

A greater amount of retention is required in landscapes that have high proportions of operable area, or where previous development has reduced wildlife tree abundance. Where landscape unit objectives are not established, use Table 1-B.

- Given the absence of landscape objectives for biodiversity, WTP retention percentages are 3% higher than in Table 1-A.

Habitat Modification Techniques

- Trees with wildlife tree-like attributes such as broken tops, decayed heartwood, and artificial cavities can be created using various techniques. These habitat modification techniques can be used for rehabilitation of sites with few/no available wildlife trees. The techniques are discussed in Creating Wildlife Trees.

Are there other recommendations that you think should be added to this list? If so, what are they?

Creating Wildlife Trees

There are several techniques used for creating wildlife trees. These techniques may be of value for restoring or enhancing wildlife tree habitat. They are not intended to replace natural retention strategies. The natural retention strategies are the preferred method.

- Stubs

- Tree topping

- Fungal inoculation

- Nestboxes and cavity construction

- Planting standing dead trees (snags)

- Blasting

- Stem girdling

Are there other techniques that can be used to create wildlife trees? If so, name and describe them.

One method of creating wildlife trees is to high-cut stumps when harvesting with mechanical feller bunchers. This leaves small standing dead trees called stubs (see Figure 11, below). Stubs provide structure within second-growth forests and create future coarse woody debris.

- Candidates for stubs should exhibit some defects in the lower bole, which reduce their timber value but enhance their habitat value.

- Stubs cannot replace attributes associated with full height wildlife trees, but still provide limited stand level structure.

Figure 11. Artificially created wildlife trees (stubs).

What should forest managers be doing to retain natural stubs? What should forest managers be doing to retain natural stubs?

Recommendations for stubs: Are there other recommendations? If so, what are they?

Stems suitable for stub creation should have some visible defect (such as a canker, scar or conk) in the lower bole and little or no lean. Trees which do not have heart rot prior to death (i.e., stubbing) will not develop this critical WLT attribute.

Tree Topping

Tree topping can be employed in situations where the installation of a no-work zone around a high value wildlife tree in order to protect the work area from aerial hazards (e.g., a large spiked top or large dead limbs on a class 2 tree) is not appropriate.

For example,

- If no net loss of operable/treatable ground on the block due to no-work zones is a management objective

- If a valuable wildlife tree with a hazardous top is present on the block (and a second management objective is to retain structural wildlife tree habitat where possible)

Then topping the tree and removing the hazard is a viable management solution.

What other hints can you add to tree topping?

Healthy class 1 trees (trees with no visible external defects) can also be topped to simulate natural breakage and promote standing dead tree recruitment. This may be appropriate in even-aged stands with little or no structural diversity. Trees can be jagged-topped to simulate natural breakage, thereby facilitating weathering and decay processes. Only highly experienced and trained personnel should be used to climb and top trees.

Is this strategy used often in BC forests? Explain.

Fungal innoculation

Inoculation of trees with wood decay fungi to promote heart rot has potential as a useful standing dead tree creation tool. However, fungal pathogens are tree species and area specific. Fungal inoculum injected into a live conifer initiates heart rot. Detailed knowledge of inoculation procedures is required for this technique to be successful (including choice of fungal species and injection parameters and procedures). Regional pathologists should be consulted if this method of treatment is being considered.

- What else do you know about fungal inoculation?

Nestboxes and cavity construction

Artificial nestboxes can provide nesting structures for a variety of hole-nesting birds. This is especially true for areas with a shortage of natural cavities.When installing nestboxes, it is essential to place the box in the appropriate habitat suitable for the intended species. This includes nest height (e.g., for predator avoidance) and nest location (e.g., proximity to water for cavity nesting ducks). Proper nestbox construction is required to ensure use of the box by the intended species. Accurate, species-specific hole size (diameter) and shape (circular, flattened oval) will usually limit use of the box to the intended species. Cavity starts for feeding, nesting, and roosting can be constructed in trees using a chainsaw (see Figure 12, below). This requires knowledge of the habitat needs of the species in question (e.g., size, shape and location of nest hole for flying squirrels), and an experienced tree climber/chainsaw operator.

- What else do you know about nestboxes and cavity construction?

Planting standing dead trees (snags)

Artificial standing dead trees can be planted in the ground with an excavator. By providing some immediate habitat structure, this technique has potential as a habitat enhancement tool on deactivated roadbeds and landings. Planted standing dead trees provide ready-made hunting perches for raptors and other birds. It is unknown if planted standing dead trees will receive increasing use by wildlife as the surrounding stand greens-up and matures. Additional research is required to determine how widespread its application should be.

- Larger diameter pieces (generally > 30 cm) with some indication of internal decay should be selected for planted standing dead trees. Trees which do not have heart rot prior to death will not develop this critical WLT attribute (i.e., minimal value).

- If available, planted standing dead trees should represent the mix of tree species, found on the block.

- Planted standing dead trees should be dug into the ground at least 1 m for every 6 m of standing dead tree height (a 12-m standing dead tree should be sunk 2 m into the ground).

Have you seen very many artificial standing dead trees in BC forests? If so, where? Elsewhere out of BC? Which of the seven categories have you seen most in B.C.:

- Stubs

- Tree topping

- Fungal inoculation

- Nestboxes and cavity construction

- Planting standing dead trees (snags)

- Blasting

- Stem girdling

Are there enough wildlife trees habitats created in BC?

Blasting the tops of trees to create standing dead trees is generally not recommended unless there are no other alternatives. A candidate tree for blasting would be:

- Unsafe to top

- A situation where the establishment of a no-work zone is considered inappropriate

Blasting trees require specialized personnel, equipment, and safety procedures

Where have you seen blasting of treetops in BC?

Stem girdling

Stem girdling is not recommended as a wildlife tree creation technique. Stem girdling results in tree death at the point of girdling. Fungal decay is initiated at this point, resulting in a tree that is prone to breaking off at girdled height (usually a few metres above ground). Stem girdled trees do not provide long-term wildlife tree habitat, and are often unstable and unsafe for workers to be around.

Do you agree with this recommendation? If so, what are some other reasons? If not, why not?

Why are wildlife trees important?

Wildlife trees at all stages provide a portion of the life support system for many species of plants, invertebrates, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Altogether, more than 80 animal species in British Columbia depend on dead or deteriorating trees. Some of the uses include nesting, feeding, communication (drumming, marking), roosting, shelter, and over wintering. Some wildlife tree users are considered threatened or endangered. In some places, loss of wildlife trees has already resulted in decreased abundance and variety of wildlife tree users, and may contribute to the eventual loss of some species.

Nine species of animals that are dependent on wildlife trees for some aspect of their life history requirements are on the provincial Red list (endangered or threatened), while 19 species are on the Blue list (sensitive or vulnerable).

Many wildlife tree users help control forest pests. Most cavity nesting birds eat insects.

For example, a recent study found that three-toed woodpeckers harvested 75 – 80% of the over winter grub population of mountain pine bark beetle in southern BC. This number of predation helps control outbreaks of forest pests.

- Are there other benefits of wildlife trees? If so, name them.

- What else do you know about mycorrhizae?

Wildlife trees are an important element of natural forest ecosystems in British Columbia. However, not all trees make good wildlife trees. In general, larger size trees, either live or dead, with a sound outer shell (but with heartrot) and intact branch and bark structure, will persist longer and make good wildlife trees over time. As well, wildlife trees are not evenly distributed throughout forest stands or across larger landscapes. Certain locations such as the areas along streams and other wet sites (riparian areas), along gullies and rocky knolls, and in stands of mixed coniferous-deciduous trees, provide more diverse habitat features. Consequently, these areas tend to provide more opportunities for feeding, shelter, nesting, and denning when compared to wildlife trees found in other locations. Natural disturbance factors such as fire, insect and disease attack also influence the distribution, structure, and longevity of wildlife trees.

For example, standing dead trees created by wild fire are often used extensively for feeding by insect eating birds within the first year or two following a fire. During this time, the dead trees are attacked by a variety of woodboring insects that deposit their eggs in the wood. The insect larvae and emerging adults provide food for woodpeckers, chickadees, and other birds.

Worker safety considerations for wildlife trees

Some wildlife trees present a hazard to workers and some do not. In general, the risk that a tree is dangerous is related to its decay class and factors such as tree defects, lean, wild exposure or slope and the type of work activity to be carried out.

The following information about safety considerations is based on the nine classifications of wildlife trees (figure 8).

Are there other worker safety considerations? If so, name them.

Only people who have successfully completed a 2-day course are certified to carry out wildlife/danger tree assessments.

Application to forest management

he application to forest management is divided into three parts:

- Silviculture, harvest area boundary, and roadside applications

- Harvesting applications

- Wildlife tree retention (WTR)

1. Silviculture, harvest area boundary, and roadside applications

Until recently, standing dead trees were routinely removed for safety reasons in all forestry operations. This represented a significant loss of habitat for some species of wildlife dependent on these trees.

In an effort to reduce this loss, the Wildlife Tree Committee has developed techniques for assessing the safety hazards, soundness, and associated habitat value of wildlife trees. These techniques can be applied to wildlife/danger tree assessment in silviculture, roadside, and harvest area and Parks/Recreation site situations, thereby giving forest managers a tool for determining the relative safety hazard and habitat value of particular wildlife trees. Appropriate management action can then be taken (e.g., work around the tree(s) as is, remove tree(s), create a no-work zone around specific trees.) thus, it is possible to maintain wildlife tree habitat in forests operations in a safe and efficient manner.

- Are there other applications? If so, list them.

- What else do you know about this topic?

2. Harvesting applications

Wildlife tree management in forest harvesting operations relies on strategies such as single tree retention and the use of reserves. Areas reserved for wildlife trees can be located within or adjacent to harvest settings and should contain both live and standing dead trees of varying sizes, species, structure, and stages of decay. Patch reserves and single trees can be accommodated in each of the silvicultural systems used in BC.

- What else do you know about harvesting applications?

Wildlife tree retention (WTR)

Wildlife tree retention (WTR) should, as a first priority, protect trees with valuable wildlife tree attributes. Where there are few trees with valuable attributes, retention should be located in areas most suitable for long-term wildlife tree recruitment.

- A diversity of WTR approaches is recommended; e.g., a range of wildlife tree patch sizes, combined with dispersed trees (there will be ecosystem-dependent variations of this recommendation).

- It is particularly important to retain uncommon species, stand characteristics, and other elements of stand-level biodiversity. Consequently, relatively uncommon tree species and features in the block and adjacent subzones should form a larger proportion of the WTR objective. Consider species that exhibit or have the potential to develop, valuable wildlife tree attributes.

- Those trees/areas chosen for WTR should be designated for retention until other suitable trees can replace them — a minimum of one rotation.

- Trees/areas chosen for WTR should be designed to minimize windthrow and the potential for contributing to insect infestation in adjacent stands.

- If trees chosen as wildlife trees have been felled or windthrown, they should be left in place to function as coarse woody debris, unless they pose a significant forest health or other concern. Selection of appropriate WTR areas should consider existing wildlife trees on the site. Planning for a diversity of wildlife tree classes will better meet future large wildlife tree and CWD objectives (including recruitment and longevity).

- How the characteristics of individual trees may affect the potential to achieve or maintain a particular stand structure (e.g., shade tolerance, tree longevity, or disease/pest resistance) should be considered when selecting appropriate retention areas. Ensure that the trees being retained have the potential to achieve the desired stand structure.

- It is important to consider natural succession and other natural factors, such as wind, when planning retention areas. Individual and patch reserves will not remain in the same condition forever, and therefore may not provide the same habitat attributes over a rotation.

- The most windfirm reserves, and therefore the most likely to remain standing after harvesting, are reserves that consider the site, stand and individual trees during layout. For individual trees, size (low height/diameter ratio) is generally a much more reliable indicator of Windfirmness than species.

- The importance of WTR areas within cutblocks increases with the size of the cutblock. WTR areas should generally be centred on the most suitable trees and distributed throughout the cutblock; distances between wildlife tree patches should not exceed 500 meters

Are you able to add more applications? List them

Conclusion

Review of learner outcomes

- Are you able to describe wildlife trees?

- Are you able to identify forest management applications for wildlife trees?

- Are you able to describe the role of wildlife trees within forest biodiversity?

Recall

This section is very long and contains a lot of information. Using a graphic organizer, recall what information was presented. This is only a partial diagram; you need to insert the details. You may find it better to place your sheet of paper in a landscape position. Use single words or phrases when adding details. Color each of the five headings and its contents a different color. Many people remember best when color is used.

Transfer of learning

As I continue do my job, what will I modify because of what I learned?

Reflections

If more people knew more about wildlife trees, how would that change the way they view forest biodiversity?