3.4 Coarse woody debris

Learner outcomes

On completion of Part 3C, you will be understand the role that the stand level component — coarse woody debris — plays in forest biodiversity and you will be able to:

- Describe coarse woody debris

- Identify forest management applications for coarse woody debris

- Describe the role of coarse woody debris in forest biodiversity

General information about CWD

Coarse woody debris (CWD) consists of fallen trees, sloughing bolewood, and other woody material on the forest floor. It is generally considered to be sound and rotting logs, stumps and branches greater than 10 cm in diameter that provide, among other things, habitat for plants, animals and insects, and a source of nutrients for soil development. Maintaining CWD after harvesting is a critical element of managing for biodiversity. In most cases, non-merchantable logs, breakages, short pieces, stumps, tops and branches left on the forest floor after harvesting provide the major source of CWD in managed stands. Ensuring that large pieces of CWD are maintained through several rotations is a significant forest management challenge.

- Define coarse woody debris. Explain each of these reasons.

CWD is important for three reasons:

- Nutrient cycling

- Seed beds

- Habitat for insects, small mammals, and amphibians

CWD roles

CWD plays numerous functional roles in natural and managed forest and aquatic ecosystems, including:

- Contributes to stand level structural diversity of old growth and mature forests

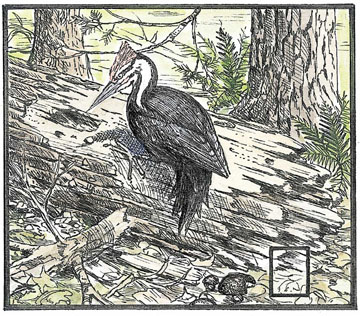

- Provides feeding, breeding, and shelter substrate for many organisms (invertebrates, small mammals, amphibians)

- Provides habitat for many forest plants, animals, (both vertebrates and invertebrates), and microorganisms

- Provides nutrients source and growing substrates for various bacteria and fungi (including beneficial mycorrhizal fungi), as well as saprophytic plants, lichens, and mosses that are important in decay, nitrogen production, and other nutrient and moisture cycling

- Carbon storage

- Erosion control

- Buffered microclimates suitable for seedling establishment

- Shelter and access routes for small mammals in periods of heavy snow cover

- Serves as a refugium for organism after disturbance, and through its persistence across disturbances

- Influences slope and stream geomorphology

- Influences forest floor microtopography and microclimate

- Contributes to nutrient and organic matter dynamics of forest ecosystems

- Influences stream habitat quantity by dispersing stream energy, releasing nutrients, and creating gradual steps, gravel bars and pools for resident and spawning fish (Caza, 1993)

- Shapes and stabilizes stream banks, and in aquatic habitats. It increases channel complexity and habitat quality by creating pools and riffles (disperse stream energy and create fish habitats).

- In streams, CWD increases litterfall retention (up to 70%), which is then decomposed by stream organisms

Are there other roles? If so, list them

In turn, CWD levels will be influenced by forest management objectives and practices, and site-specific conditions and operational constraints, (fuel/residue loading concerns, type of silvicultural system, harvesting method, site preparation, and slope and soil stability [Radcliffe et al., 1994]) (see selected literature, below).

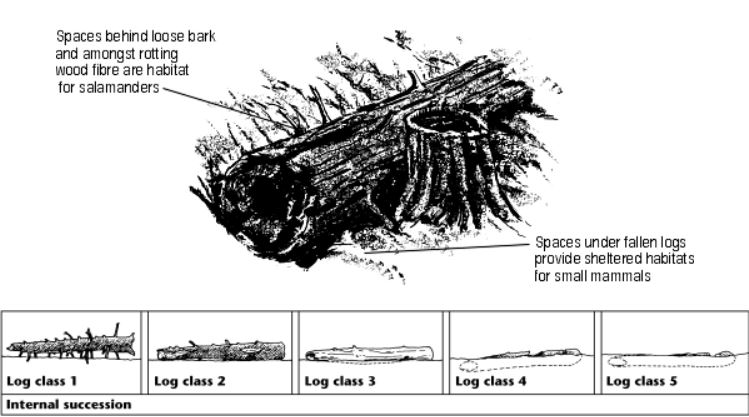

Log decomposition stages are shown in Figure 13 (below).

Selected literature

- Alexander, R. R. (1987). Ecology, silviculture and management of Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir type in central and southern Rocky Mountains. USA: USDA Forest Service. Agriculture Handbook. No. 659.

- Bartels, R., Dell, J. D., Knight, R. L., & Schaefer, G. (1985). Dead and down woody material. In Brown op cit. pp. 171-186.

- Biodiversity guidebook. (1995). Victoria: British Columbia Ministry of Forests and Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, www.for.gov.bc.ca/tasb/legsregs/fpc/fpcguide/biodiv/biotoc.htm

- Brown, E. R. (ed.). (1985). Management of wildlife and fish habitats in forests in western Oregon and Washington. Portland: USDA Forestry Service. Pub. No. R6-Fowl-192.

- Caza, C. L. (1993). Woody debris in the forests of BC: a review of the literature and current research. Victoria: BC Ministry of Forests, Land Mgmt. Rep. No 78.

- Franklin, J. F., Berg, D. R., Thornburgh, D. A., & Tappeiner, J.C. (1997.) Alternative silvicultural approaches to timber harvesting: variable retention harvest systems. In Kohn, K. A. & Franklin, J. F. (Eds.), Creating a Forestry for the 21st Century: The Science of Ecosystem Management. (pp. 111-139). Washington: Island Press.

- Franklin, J. F, Perry, D.A., Schowalter, T. D., Harmon, M. E., McKee, A., & Spies, T. A. (1989). Importance of ecological diversity in maintaining long-term site productivity. In Meurisse, R., Thomas, R., Boyle, J., Means, J., Perry, C. R., & Power, R. F. (Eds.). Maintaining the long-term productivity of Pacific Northwest forest ecosystems. Portland: Timber Press.

- Guy, S. E. & Manning, E. T. (2001). Wildlife/danger tree assessor's course workbook. Victoria: Ministry of Forests & Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks.

- Harris, L. D. (1984). The fragmented forest, island biogeography theory and the preservation of biotic diversity. Chicago: University Chicago Press.

- Hunter, M. L. (1994). Wildlife, forests, and forestry: principles of managing forests for biological diversity. New Jersey: Regents/Prentice Hall.

- Machmer, M. & Steeger, C. (1995). The ecological roles of wildlife tree users in forest ecosystems. Victoria: Ministry of Forestry. Land. Manage. Handbook. No. 35.

McNeely, J. A, Miller, K. R., Reid, R. A., Mttermeier, R. A., & Werner, T. B. (1990). Conserving the world's biological diversity. Prepared and published by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Nature Resources, World Resources Institute, Conservation International, World Wildlife Fund-US, and the World Food Bank. - Park, A. & McCulloch, L. (1993). Guidelines for maintaining biodiversity during juvenile spacing. Victoria: Ministry of Forestry and FRDA Report.

- Radcliffe, G. B. Bancroft, Porter, G., & Cadrin, C. (1994). Biodiversity of the Prince Rupert forest region. Victoria: Ministry of Forests. Land Management Rep. No. 82.

Riparian management area guidebook. (1995). Victoria: British Columbia Ministry of Forests and Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. - Stathers, R. J., Rollerson, T. P., & Mitchell, S. J. (1994). Windthrow handbook for British Columbia forests. Victoria: Ministry of Forest. Working Paper 9401.

- Thomas. J. W. (ed.). (1979). Wildlife habitats in managed forests: the Blue Mountains of Oregon and Washington. Washington: Forestry Service. Agriculture Handbook No. 553.

Maintaining CWD

Maintaining coarse woody debris (CWD) post-harvesting is a critical element of managing for biodiversity. CWD should be managed in conjunction with WTPs, individual leave trees, and other reserve areas. Standing trees are the source of future CWD. Some practices can be modified to help address requirements for CWD. Post-harvest CWD volume objectives may be met with post-logging waste and residue for first rotation harvesting. This will not be the case in situations where whole-tree harvesting, clean site preparation practices, or excessive salvage of material not considered merchantable under current utilization standards, are employed.

Coniferous material lasts many times longer than deciduous material and therefore remains part of the useable structure of a stand for much longer time. In mixed wood ecosystems, coniferous material is generally more valuable than deciduous material. CWD can be managed in conjunction with wildlife trees and other constrained or reserve areas. Standing live and dead trees and/or stubs retained on cutblocks represent important sources of CWD recruitment.

CWD has additional value in riparian areas, which are a valuable habitat resource for many species of wildlife. CWD can provide habitat for fish, invertebrates and vegetation. Most importantly, it contributes to stream geomorphology. However, excessive amounts of fine woody debris can have negative effects on stream biology. When developing objectives for CWD, consider other objectives such as forest health and fuel loading.

An assessment of CWD can follow the standardized methodology outlined by the Resource Information Standards Committee.

- How do/could you use this information in your workplace? What else do you need to know about CWD? Where can you locate it?

CWD applications for forest management

There are many coarse woody debris (CWD) applications for forest management.

- Dispersed CWD is preferred over large accumulations.

- Avoid large accumulations, especially on landings and roadsides, bearing in mind that some accumulations will be inevitable for reasons of safety and operability. Some small CWD piles dispersed in cutblocks may be appropriate to provide valuable habitat for some mammals. However, keep large pieces of CWD out of roadside/landing piles.

- Maintain residue and waste well distributed across the block (avoid practices such as piling and burning). However, CWD should be concentrated near special habitats such as riparian areas where present.

- Leave non-merchantable material on site

- Leave acceptable levels of blowdown on site as CWD The silviculture prescription should identify acceptable levels of windthrow or other damage in WTPs or other areas beyond which salvage may occur.

- Move CWD off trails to decay naturally

- Where provision of small mammal and furbearer habitat (Marten) is a management objective, CWD can be piled in short, low-height windrows (<=1 m high), or piled on top and around large stumps.

- Larger pieces of CWD are more valuable than smaller pieces — they last longer, hold more moisture, and are useable structures for a greater number of organisms.

- Leave a range of piece sizes (small to large for diameter and length)

- If woody debris must be chipped, spread the chips thinly (<10 cm deep) on the forest floor to maintain biomass levels on site — chipping is not, however, recommended.

- Minimize movement of pieces of CWD

- Small piles and windrows are acceptable, but, where possible, CWD scattered across a site is more valuable

- If piling, mix pile treatment with scatter treatment

- If windrowing, break up windrows

- In traveled or high use areas, slash CWD to the ground (this helps prevent potential injury from suspended logs)

- Modify whole-tree harvesting by limbing and topping on site

- Ecologically, it is advantageous to maintain the full range of decay and diameter classes and species of CWD on every site — different organisms and ecosystem processes require CWD in different stages of decay (hard to soft). The faster decay rate of deciduous CWD likely provides significant short-term ecological benefits.

- During reforestation, if required, modify stocking standards to meet CWD objectives (i.e., due to debris accumulation and number of plantable spots)

- During stand tending, use variable density spacing, plan for retention of WTPs, and maintain some deciduous species to recruit CWD

- Balance objectives for coarse woody debris with other management objectives (firewood supply, fire hazard, backcountry vs. urban interface)

- Manage the composition and arrangement of CWD within acceptable levels of risk for wildfire, insect pests and forest disease outbreaks.

- Harmonize the retention of CWD with all other silvicultural objectives.

- Maintain variability in the levels of CWD at the landscape level.

- The natural distribution and amounts of CWD will vary according to biogeoclimatic gradients, stand types, and stand development history.

- Although the natural distributions of CWD cannot be mimicked exactly, it is important that CWD management captures landscape variation and site-specific variations through different management practices.

- During reforestation, site-specific, inter-tree spacing distances may be appropriate to meet CWD objectives.

- During stand tending, plan for retention of WTPs, use variable density spacing, and maintain some deciduous species to recruit CWD.

Are there other application recommendations that you think could be added? Name them.

How do/could you use these recommendations in your work? If not, why not?

CWD retention and timber harvesting methods

CWD can be managed during harvesting in a number of different ways. Some of the methods to consider are:

- Retaining green trees and standing dead trees for future CWD recruitment

- Extending the rotation of certain sites to provide larger CWD

- Reducing the impacts of slashburning by spring burning, avoiding broadcast burning, or using spot treatments

- In feller-buncher operations, creating stubs trees defective in the butt (from WLT class 1, 2 or 3), as those will serve as CWD recruitment

- Piling debris on larger stumps, throughout areas where ground based harvesting is used

Selecting a CWD management strategy must be compatible with other management objectives, and applied on a site-specific basis. One strategy is not always going to work on all sites.

CWD management must be considered in relation to the following:

- The ability to perform site preparation activates

- The ability to meet reforestation stocking objectives

- Increased CWD levels that may increase fire hazard, or forest health problems

- Implications to growth and yield and AAC levels

- Worker safety concerns in subsequent stand tending activities

Wildlife Tree & Course Woody Debris Guidance & Policies

Coarse woody debris — Conclusion

Review of learner outcomes

- Are you able to describe coarse woody debris?

- Are you able to identify forest management applications for coarse woody debris?

- Can you describe the role of coarse woody debris in forest biodiversity?

If you cannot complete these questions, what will you do so that you are able to?

Recall

Think about the last time you were in the forest and many of the recommendations for maintaining coarse woody debris were implemented.

- What would it look like?

- What sounds would you hear?

Use a T-chart to write your thoughts.

- On the left side of the T, list what the coarse woody debris in a forest would look like. (What would you see?)

- On the right side of the T, list what the coarse woody debris in the forest would sound like. (What sounds would you hear?)

Transfer of Learning

If you were invited to a grade six class to talk to their science class about the role of coarse woody debris in forest biodiversity, what 4 – 6 ideas would you emphasize?

Reflections

What was the most significant idea or concept that you learned in this part of the module?