White pine blister rust

White pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola) is one of the most damaging non-native tree pathogens in B.C. It originates from Siberia and arrived in B.C. around 1910, and spread across most of the province by 1930.

On this page

White pine blister rust impacts only five-needle pines: limber, western white and whitebark. These are three very important tree species in B.C. Western white pine once formed one of the most productive (volume) forest types in the interior West. Ecologically, whitebark pine is considered a foundational species for high elevation wildlife. Limber pine is the rarest conifer in B.C. Both whitebark pine and limber pine are considered endangered, primarily due to widespread mortality suffered through white pine blister rust.

A considerable amount of research has been directed towards developing disease resistance. The identification of trees exhibiting natural resistance mechanisms has led to a genetic screening program in B.C. Now, disease resistant western white pine stock is routinely planted. A new program for developing disease resistance in B.C. whitebark pine is beginning to identify natural resistance in this species. Limber pine screening has not begun in Canada.

Description

This is the only stem rust occurring on five-needle pines in B.C. Branch flagging, caused by cankers girdling the branches, is evident throughout the year and frequently a prominent indicator of infection. Cankers on stems and branches begin as orange swellings. Cankers often have a diamond shape on stems with smooth bark. Whitish blisters, which rupture to expose orange spores are produced on the cankers during the growing season. As cankers age, the bark covering them becomes dark, rough, swollen (often with resinosis), and can be colonized by secondary insects and fungi. Rodents frequently gnaw the resin soaked bark surrounding cankers. Cankers may become temporarily inactive, with no resinosus or sporulation evident.

Active white pine blister rust canker on whitebark pine near Slocan City, B.C.

In general, smaller trees are killed more quickly because cankers are able to readily girdle narrow stems. Whereas, infections can take years to completely encircle large stems. Once complete, all living tissue above the stem canker dies rapidly. Thus, it’s very common to see five-needle pines with dead tops. Canker infections can continue to thrive at the base of the dead tree segment for years and slowly spread downward. Similar dynamics occur on infected branches. The closer the branch canker is to the main stem, the greater chances of spread reaching the bole. Cankers more than 30 to 60cm from the bole are insignificant threats because mycelia is unlikely to spread this far. However, the distal portion of a branch beyond a severe canker will typically die.

Visible impacts of white pine blister rust in a stand on Meteor Mountain (note the dead trees and the rust-killed tree top).

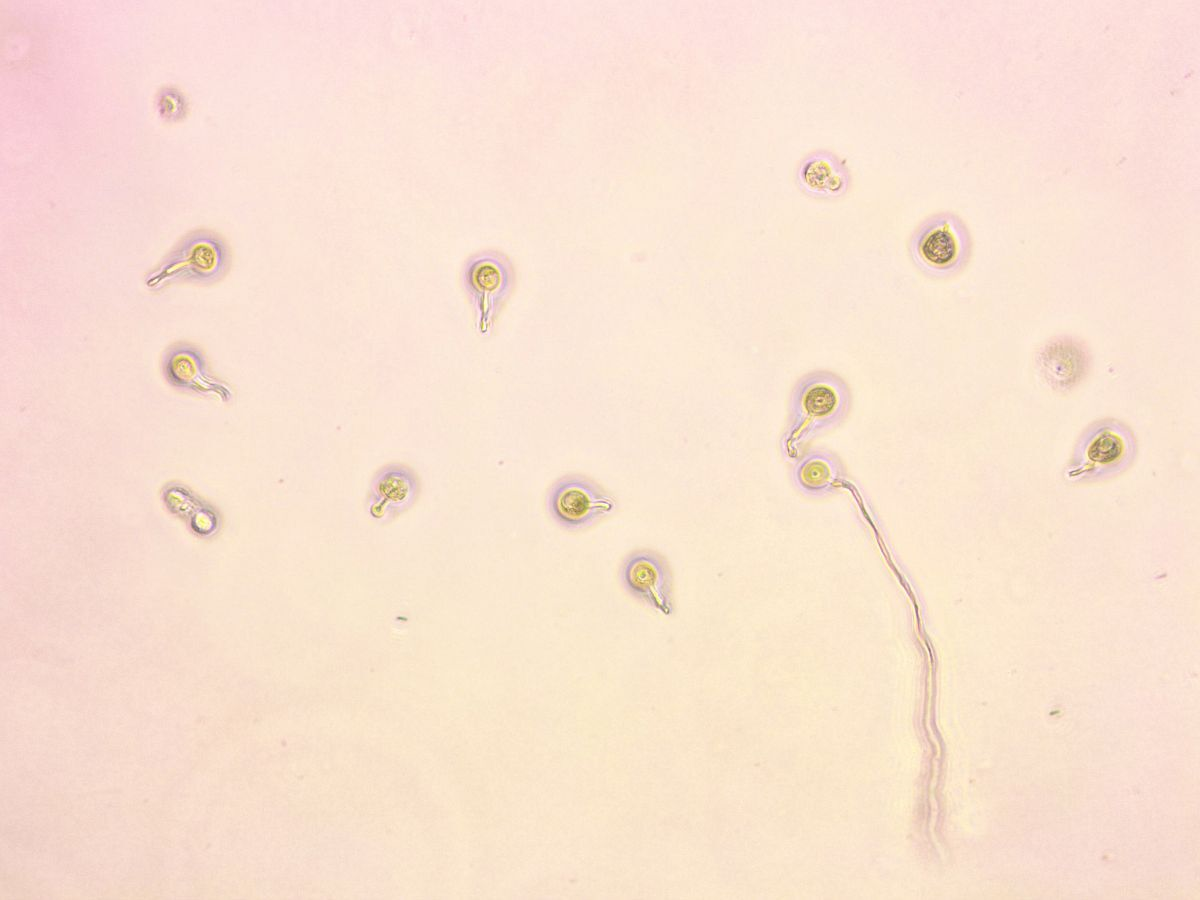

This disease does not spread directly from tree to tree. Rather, there is a very complex life cycle relying on alternating spore types and multiple hosts. The primary alternate hosts are species of Ribes (currants and gooseberries). The transfer of spores occurs in five separate stages, with each requiring specific environmental conditions. During the infection stage, basidiospores land on needles, germinate and infect through the stomata. The fungus develops within the tree tissue and eventually creates a canker near the infection.

Management

White pine blister rust is considered high hazard in all ecosystems across the province, even outside of the natural range of five-needle pines. Strategies to address impacts of white pine blister rust typically focus on ecosystem conservation (primarily whitebark and limber pine) or improving timber yield (primarily western white pine). It’s generally agreed that eradicating this fungal disease from North America is not feasible. Thus, management should emphasize treatments of the host. Fundamentally, the successful maintenance of five-needle pines relies on the availability of native tree genotypes naturally resistant to white pine blister rust. Much success has been gained promoting resistance in western white pine. Building upon this, preliminary efforts are underway to identify resistant whitebark pine trees in B.C.

Ecosystem conservation:

As a non-native fungal pathogen, the blister rust disease greatly impacts the integrity of B.C.’s five-needle pine ecosystems. Conserving host genetic resistance is critical, especially from those rare wild trees that are naturally resistant to blister rust. In B.C., whitebark pine parent trees are being screened for resistance. This process is modeled from the successful white pine approach and the current US Forest Service five-needle pine screening program. Every year, new candidates are screened. The screening process requires at least five years to assess each parent tree. Once confirmed, resistant parent trees are protected from other agents (e.g. fire and insects) in order to serve as seed sources. The development of one or more seed orchards producing resistant seeds will greatly economize a steady supply of seeds. Currently, less than ten thousand whitebark pine seedlings are being planted each year. This stock originates from 1) best performing parents in screening program, and 2) unscreened but healthy trees that are surrounded by diseased trees. There are opportunities to increase ecosystem restoration planting of all three pine species, especially in the southern Interior where they are more common.

Planting whitebark pine seedlings in Murray Ridge, B.C.

Timber production:

White pine has historically been one of the leading timber producing species in the southern portion of B.C. Historically, in the Kootenay region, associated stands commonly produced 50,000 board feet per acre which is about half of what mixed fir stands, replacing white pine, are producing nowadays. By promoting western white pine, timber yield can improve.

A proper strategy to manage disease for timber yield can begin during the establishment of plantations. Harvesting methods to reduce the establishment of Ribes can include reducing ground disturbance. This may be accomplished by harvesting during winter snow cover plus retaining some overstory to reduce light levels available for Ribes seed germination. Planting rust-resistant stock is necessary. Available stock in B.C. typically has about a 65% success rate for growing canker-free.

Stand tending actions can also affect disease impacts. Two types of pruning can be applied to young stands. A stand-wide pruning is a preventative measure that removes all white pine branches below a pre-determined height (typically 50% of a tree’s height). Infections occur much more commonly in the lower crown and this practice has proven successful in many research trials. Another type of pruning, called ‘sanitation pruning’, targets only those branches that have cankers that are likely to spread to the tree bole. Typically, cankers within 30 cm of the bole present the highest risk. An additional stand tending practice commonly practiced is thinning. This activity has yielded inconsistent results on disease expression as discussed by Zeglen and others (2010).

Blister Rust Infected Whitebark Pine Map (JPG, 542KB)

References

Murray, M.P. and J. Krakowski. 2013. Silvicultural options for the endangered whitebark pine. Silviculture Magazine. Winter: 22-23.

Zeglen, S., et al. 2010. Silvicultural management of white pines in western North America. Forest Pathology 40(3‐4):347 – 368.

White pine blister rust basidiospores that infect pine needles. Germination tubes typically emerge within hours of infection.

Screening whitebark pine seedlings for white pine blister rust resistance at the Kalamalka Forest Research Center in Vernon, B.C.