Palliative Care for the Patient with Incurable Cancer or Advanced Disease - Part 2: Pain and Symptom Management

Effective Date: February 22nd, 2017

Palliative Care Part 1: Approach to Care

Palliative Care Part 3: Grief and Bereavement

Scope

This guideline presents strategies for the assessment and management of cancer pain, and symptoms associated with advanced disease, in patients ≥ 19 years of age. Part 2 is divided into seven sections, providing recommendations for evidence-based symptom management with algorithms to facilitate quick access to the information required. Hyperlinked notes in the algorithm refer back to more detailed information within each symptom section.

|

Key symptom areas addressed are: Associated Documents |

Diagnostic Code: Neoplasm of unspecified nature: 239

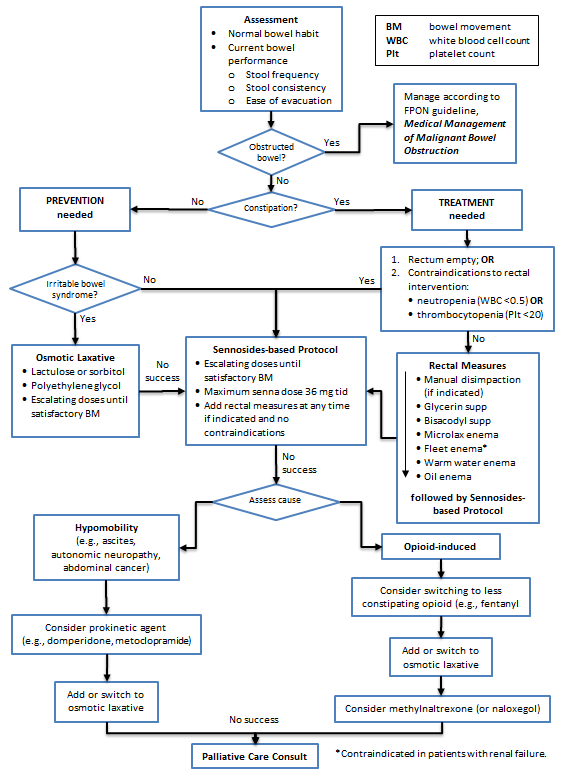

Key Recommendations | Assessment | Management | Constipation Management Algorithm | References | Appendices

Key Recommendations

- Prevent constipation by ordering a bowel protocol when regular opioid medication is prescribed.

Assessment

- Understand the patient’s bowel habits, both current and when previously well (e.g., frequency of bowel movements (BMs), stool size, consistency, and ease of evacuation). Consider using the bowel performance scale available at: /assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/bc-guidelines/palliative2_constipation_medtable.pdf

- The goal is to restore a patient’s normal BM frequency, consistency, and ease of passage.

- For lower performance status patients (e.g., reduced food intake and activity), lower BM frequency is acceptable as long as there is no associated discomfort.

Management

- There are many etiologies (e.g., reduced food/fluid/mobility and adverse effects of medications).

- Exclude impaction when a patient presents already constipated. Abdominal x-ray can be useful when physical examination is inconclusive.

- Minimize/avoid rectal interventions (enemas, suppositories, manual evacuation), except in crisis management. Note that rectal interventions are contraindicated when there is potential for serious infection (neutropenia) or bleeding (thrombocytopenia), or when there is rectal/anal disease.

- When risk factors are ongoing, as they are in most cancer patients, suggest laxatives regularly versus prn. Adjust dose individually. Laxatives are most effective when taken via escalating dose according to response, termed “bowel protocol”.

- Sennosides (e.g., Senokot®) are the first choice of laxative for prevention and treatment. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome may experience painful cramps with stimulant laxatives and often prefer osmotic laxatives such as lactulose or polyethylene glycol (PEG). There is weak evidence that lactulose and sennosides are equally effective;1 however lactulose can taste unpleasant and cause bloating.

- If rectal measures are required, generally a stimulant suppository is tried first, then an enema as the next option.

- The BC Palliative Care Drug Plan covers laxatives written on a prescription for eligible patients.

- For patients with opioid-induced constipation, after a trial of first-line recommended stimulant laxatives and osmotic laxatives, methylnaltrexone (or nalaxegol) may be helpful. Cancer, GI malignancy, GI ulcer, Ogilvie’s syndrome and concomitant use of certain medications (e.g., NSAIDs, steroids and bevacizumab) may increase the risk of GI perforation in patients receiving methylnaltrexone. [Health Canada MedEffect Notice: http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2010/14087a-eng.php]

- A bowel protocol and patient handouts on constipation are available at: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-professionals/networks/family-practice-oncology-network/guidelines-protocols.

Constipation Management Algorithm (Click image to access full-scale PDF version)

List of Abbreviations

| AEs | adverse effects |

| BM | bowel movement |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| NSAIDs | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

References

- Agra Y, Sacristán A, González M, et al. Efficacy of senna versus lactulose in terminal cancer patients treated with opioids. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15(1):1-7.

Appendices

- Constipation Management Algorithm (PDF, 43KB)

- Appendix A - Medications Used in Palliative Care for Constipation (PDF, 121KB)

For additional guidance on constipation, see also the BC Inter-professional Palliative Symptom Management Guidelines produced by the BC Centre for Palliative Care, available at: www.bc-cpc.ca/cpc/symptom-management-guidelines/

Key Recommendations | Definition | Assessment | Management | Delirium Management Algorithm | References | Appendices

Key Recommendations

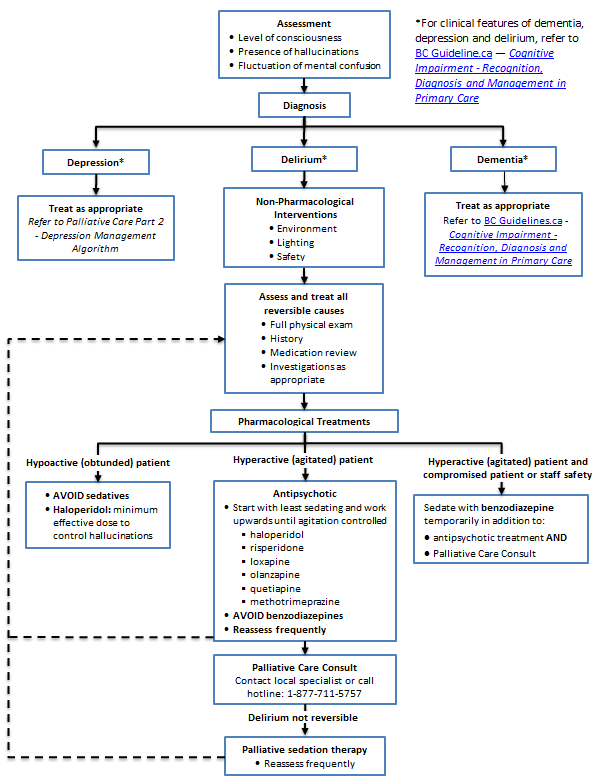

- Look for and treat reversible causes of delirium.

- Utilize neuroleptics first line for pharmacological treatment.

Definition

Delirium is a state of mental confusion that develops quickly, usually fluctuates in intensity, and results in reduced awareness of and responsiveness to the environment. It may manifest as disorientation, incoherence, and memory disturbance.

Assessment

- Delirium may be hypoactive, hyperactive or mixed.

- Look for underlying reversible cause (refer to Fraser Health Authority, Hospice Palliative Care Symptom Guidelines - Delirium/Restlessness at www.fraserhealth.ca/media/07FHSymptomGuidelinesDelirium.pdf)

- Ascertain stage of illness and whether delirium is likely to be reversible, or terminal and irreversible.

- Review advanced care plan and discuss goals of care with substitute decision maker.

- Refer patient/family to Home and Community Care (see Associated Document: Resource Guide for Practitioners) or timely access to caregiver support and access to respite and/or hospice care.

Management

- Treat reversible causes if consistent with goals of care.

- Avoid initiating benzodiazepines for first line treatment.

- Avoid use of antipsychotics in patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease or Lewy Body Dementia.

Delirium Management Algorithm (Click image to access full-scale PDF version)

List of Abbreviations

| IM | intramuscular |

| IV | intravenous |

| PO | by mouth |

| SC | subcutaneous |

References

- Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, Pereira JL, Hanson J, Suarez-Almazor ME, et al. Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2000 Mar 27;160(6):786–94.

- Macleod AD. Delirium: the clinical concept. Palliat Support Care. 2006 Sep;4(3):305–12.

- Gagnon P, Allard P, Mâsse B, DeSerres M. Delirium in terminal cancer: a prospective study using daily screening, early diagnosis, and continuous monitoring. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000 Jun;19(6):412–26.

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health. Guidelines on the Assessment and Treatment of Delirium in Older Adults at the End of Life [Internet]. 2010. Available from: http://ccsmh.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/NatlGuideline_DeliriumEOLC.pdf

- Brown S, Degner LF. Delirium in the terminally-ill cancer patient: aetiology, symptoms and management. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2001 Jun;7(6):266–8, 270–2.

- Leonard M, Raju B, Conroy M, Donnelly S, Trzepacz PT, Saunders J, et al. Reversibility of delirium in terminally ill patients and predictors of mortality. Palliat Med. 2008 Oct;22(7):848–54.

Appendices

- Delirium Management Algorithm (PDF, 34KB)

- Appendix A - Medications Used in Palliative Care for Delirium and Terminal Agitation (PDF, 125KB)

For additional guidance on delirium, see also the BC Inter-professional Palliative Symptom Management Guidelines produced by the BC Centre for Palliative Care, available at: www.bc-cpc.ca/cpc/symptom-management-guidelines/

Depression

Key Recommendations | Assessment | Management | Depression Management Algorithm | References | Appendices

Key Recommendations

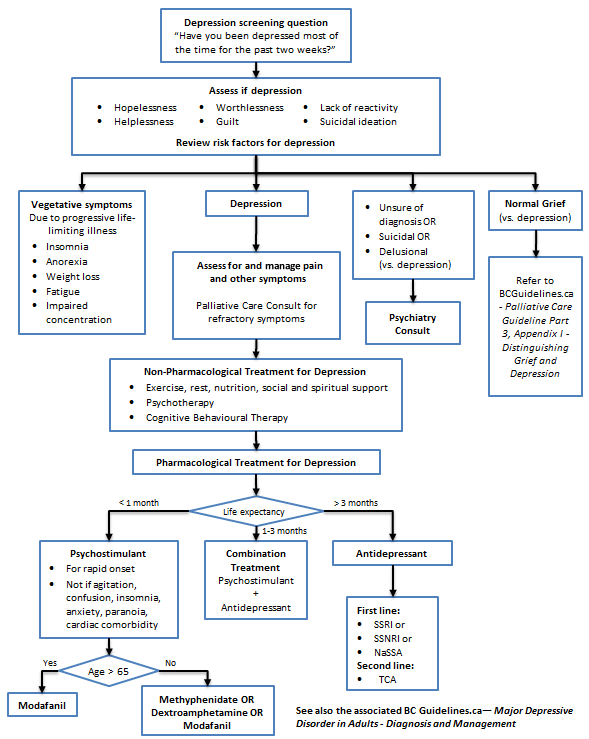

- Before diagnosing and treating major depressive disorder, first effectively treat pain and other symptoms, then differentiate the symptoms of depression from normal grieving.

- When prescribing antidepressants for this group of patients, select antidepressants with the least drug interactions.

Assessment

- Depression occurs in 13-26% of patients with terminal illness,1,2 can amplify pain and other symptoms, and is often recognized too late in a patient’s life.

- Patients are at high risk of suicide and have an increased desire for hastened death.3

- A useful depression screening question is, “Have you been depressed most of the time for the past two weeks?”4

- A diagnosis of depression in the terminally ill may be made when at least two weeks of depressed mood is accompanied by symptoms of hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness, guilt, lack of reactivity, or suicidal ideation.

- DSM-IV criteria for depression are not very helpful because vegetative symptoms like anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, insomnia, and impaired concentration may accompany end stage progressive illness.

- Risk factors for depression include:

- personal or family history of depression;

- social isolation, concurrent illnesses (e.g., COPD, CHF);

- alcohol or substance abuse;

- poorly controlled pain;

- advanced stage of illness;

- certain cancers (head and neck, pancreas, primary or metastatic brain cancers);

- chemotherapy agents (vincristine, vinblastine, asparagines, intrathecal methotrexate, interferon, interleukin);

- corticosteroids (especially after withdrawal); and

- abrupt onset of menopause (e.g. withdrawal of hormone replacement therapy, use of tamoxifen).

Management

- Non-pharmacological treatments are the mainstay of treatment for the symptom of depression without a diagnosis of primary affective disorder.

- Treatment of pain and other reversible physical symptoms should occur before initiating antidepressant medication.

- If a diagnosis of primary affective disorder is uncertain in a depressed patient, consider psychiatric referral and a trial of antidepressant medication (refer to Appendix A: Medications Used in Palliative Care for Depression). Consider drug interactions, adverse side effect profiles, and beneficial side effects when choosing an antidepressant.

- In the terminally ill, start with half the usual recommended starting dose of antidepressant.5

- First line therapy is with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI),2 selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI), or noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA).

- Tricyclic antidepressants (especially nortryptiline and desipramine) can be considered due to their co-analgesic benefit for neuropathic pain (refer to Appendix A: Medications Used in Palliative Care for Depression). Avoid with constipation, urinary retention, dry mouth, orthostatic hypotension, or cardiac conduction delays.

- When anticipated survival time is short, consider psychostimulants due to their more immediate onset of effect,2 but avoid them in the presence of agitation, confusion, insomnia, anxiety, paranoia, or cardiac comorbidity.

- If life expectancy is 1-3 months, start a psychostimulant and an antidepressant together and then withdraw the stimulant while titrating the antidepressant upwards.

Depression Management Algorithm (Click image to access full-scale PDF version)

List of Abbreviations

| ABG | arterial blood gas |

| CHF | congestive heart failure |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4thedition |

| NaSSA | noradrenergic & specific serotonergic antidepressant |

| SSRI | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| SSNRI | selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor |

| TCA | tricyclic antidepressant |

References

- Lloyd-Williams M, Friedman T. Depression in palliative care patients – a prospective study. Eur J Cancer Care 2001;10:270-4.

- Fraser Health Authority. Hospice Palliative Care Symptom Guidelines. Depression. c2006. Available from: http://www.fraserhealth.ca/media/08FHSymptomGuidelinesDepression.pdf.

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA 2000;284:2907-11.

- Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. “Are you depressed?” Screening for depression in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154:674-6.

- Rodin G, Katz M, Lloyd N, et al. The management of depression in cancer patients: A clinical practice guideline. Cancer Care Ontario. 2006 Oct.

Appendices

- Depression Management Algorithm (PDF, 35KB))

- Appendix A - Medications Used in Palliative Care for Depression (PDF, 126KB)

Dyspnea

Key Recommendations | Definition | Assessment | Management | Dyspnea Algorithm | References | Appendices

Key Recommendations

- Use opioids first line for pharmacological management of dyspnea for patients with incurable cancer.

- Use of opioids in the non-cancer population for breathlessness, especially those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), needs extreme caution and probable consultation with a Palliative Care Physician.

Definition

Dyspnea is breathing discomfort that varies in intensity but may not be associated with hypoxemia, tachypnea, or orthopnea. It occurs in up to 80% of patients with advanced cancer.1

Assessment

Investigations and imaging should be guided by stage, prognosis, and whether results will change management.

- Ask the patient to describe dyspnea severity using a 1-10 scale.

- Identify underlying cause(s) and treat as appropriate.2

- History and physical exam lead to accurate diagnosis in two-thirds of cases.3

- Investigations: CBC/diff, electrolytes, creatinine, oximetry +/- ABGs and pulmonary function, ECG, BNP when indicated.

- Imaging: Chest x-ray and CT scan chest, when indicated.

Management

- Proven therapy includes opioids for relief of dyspnea. For non-cancer patients with breathlessness, especially those with COPD, use of opioids requires extreme caution and consultation with a Palliative Care Physician should be considered.4

- Oxygen is only beneficial for relief of hypoxemia.5

- Adequate control of dyspnea relieves suffering and improves a patient’s quality of life.6

- Treat reversible causes where possible and desirable, according to goals of care.

- Always utilize non-pharmacological treatment: education and comfort measures.

Pharmacological Treatment

Opioids, +/- benzodiazepines or neuroleptics, +/- steroids.

| Drug | Comments |

|---|---|

| 1. Opioids (drugs of first choice) |

|

| 2. Benzodiazepines |

|

| 3. Neuroleptics |

|

| 4. Corticosteroids |

|

| 5. Supplemental O2 |

|

- Kobierski, L et al. Hospice Palliative Care Program. Symptom Guidelines. Fraser Health Authority. 2009 April. Available at: https://www.fraserhealth.ca/employees/clinical-resources/hospice-palliative-care.

- Schwartzstein RM, King TE, Hollingsworth H. Approach to the patient with dyspnea. UpToDate. 2009 Jan 1;17.1.

- Membe SK, Farrah K. Pharmacological management of dyspnea in palliative cancer patients: Clinical review and guidelines. Health Technology Inquiry Service. Canadian Agency for Drugs & Technologies in Health. 2008 July.

- Vozoris NT, Wang X, Fischer HD, et al. Incident opioid drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with COPD. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 683–693.

- Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):141-6.

- Kobierski et al, “Dyspnea”, Hospice Palliative Care Program Symptom Guidelines, Fraser Health Authority, 2006.

- Fraser Health Authority. Hospice Palliative Care Symptom Guidelines - Dyspnea. 2009. Available at: http://www.fraserhealth.ca/media/Dyspnea.pdf.

List of Abbreviations

| ABG | arterial blood gas |

| BNP | brain natiuretic peptide |

| CBC/diff | complete blood count and differential count |

| CT | computed tomography |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| IV | intravenous |

| PO | by mouth |

| SC | subcutaneous |

| SL | sublingual |

| SVC | superior vena cava |

Appendices

- Dyspnea Management Algorithm (PDF, 35KB)

- Appendix A - Medications Used in Palliative Care for Dyspnea and Respiratory Secretions (PDF, 126KB)

For additional guidance on dyspnea, see also the BC Inter-professional Palliative Symptom Management Guidelines produced by the BC Centre for Palliative Care, available at: www.bc-cpc.ca/cpc/symptom-management-guidelines/

Fatigue and Weakness

Key Recommendations | Definition | Assessment | Management | Fatigue and Weakness Management Algorithm | Reference | Appendices

Key Recommendations

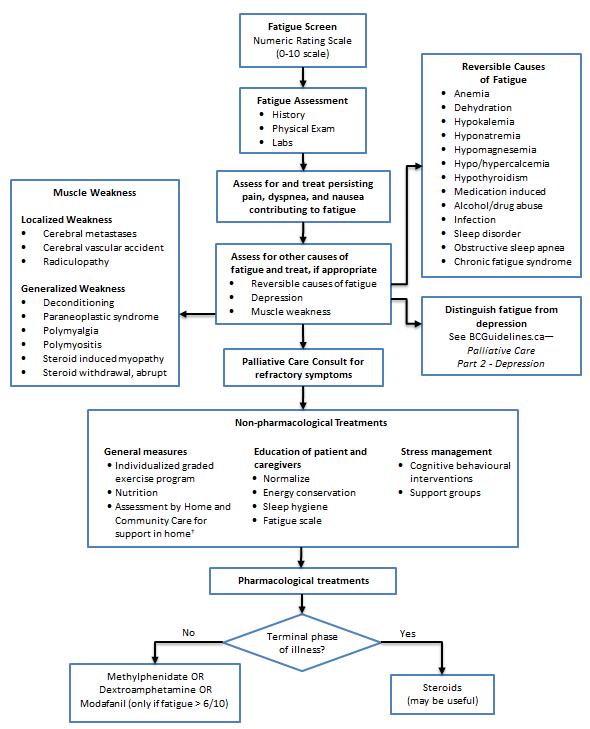

- Except when a patient is dying, recognize that fatigue is a treatable symptom with a major impact on quality of life.

Definition

Fatigue is a subjective perception/experience related to disease, emotional state and/or treatment. Fatigue is a multidimensional symptom involving physical, emotional, social and spiritual well-being and affecting quality of life.1

Assessment

- Asses whether symptom is fatigue or weakness (generalized or localized).

- Distinguish fatigue from depression.

- Look for reversible causes of fatigue or weakness (refer to Fraser Health, Hospice Palliative Care Symptom Guidelines, Fatigue, available at https://www.fraserhealth.ca/-/media/Project/FraserHealth/FraserHealth/Health-Professionals/Professionals-Resources/Hospice-palliative-care/11FHSymptomGuidelinesFatigue.pdf.

Management

- After treating reversible causes and providing non-pharmacological treatment recommendations, consider pharmacological treatment (refer to Appendix A: Medications Used in Palliative Care for Fatigue), if consistent with patient’s goals of care.

Fatigue and Weakness Management Algorithm (Click image to access full-scale PDF version)

Reference

- Ferrell BR, Grant M, Dean GE, Funk B, Ly J. Bone tired: The experience of fatigue and impact on quality of life. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1996;23(10):1539-47.

Appendices

- Fatigue and Weakness Management Algorithm (PDF, 34KB)

- Appendix A - Medications Used in Palliative Care for Fatigue (PDF, 120KB)

For additional guidance on fatigue, see also the BC Inter-professional Palliative Symptom Management Guidelines produced by the BC Centre for Palliative Care, available at: www.bc-cpc.ca/cpc/symptom-management-guidelines/

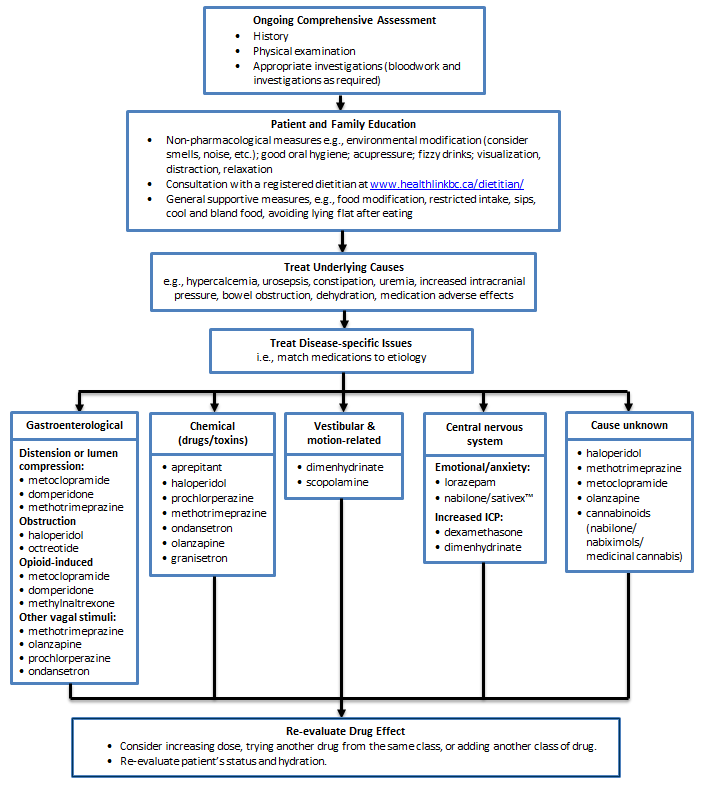

Nausea and Vomiting

Key Recommendations | Assessment | Management | Nausea and Vomiting Management Algorithm | Appendices

Key Recommendations

- Select anti-nausea medication based on the etiology of the nausea and vomiting.

Assessment

- Nausea and vomiting are common, but can be controlled with antiemetics.

- Identify and discontinue medications that may be the cause.

- Further assessment may include lab tests and imaging to investigate (e.g., GI tract disturbance, electrolyte / calcium imbalance, intracranial disease, and sepsis).

- Good symptom control may require rehydration, which can be carried out in the home, hospice, or residential care facility using hypodermoclysis, a simple, safe and effective technique that avoids venous access (refer to Appendix A - Hypodermoclysis Protocol).

Management

- Non-pharmacological: modifications to diet (e.g., small bland meals) and environment (e.g., control smells and noise), relaxation and good oral hygiene, and acupressure (for chemotherapy-induced acute nausea, but not for delayed symptoms).

- Pharmacological: match treatment to cause (e.g., if opioid-induced, metoclopramide (sometimes IV or SC initially) and domperidone are most effective). Most drugs are covered by the BC Palliative Care Drug Plan, except olanzapine and ondansetron (refer to Appendix B – Medications Used in Palliative Care for Nausea and Vomiting).

- Consider pre-emptive use of anti-nauseates in opioid-naive patients.

List of Abbreviations

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| IV | intravenous |

| N&V | nausea & vomiting |

| SC | subcutaneous |

Appendices

- Nausea and Vomiting Management Algorithm (PDF, 34KB)

- Appendix A - Hypodermoclysis Protocol (PDF, 121KB)

- Appendix B - Medications Used in Palliative Care for Nausea and Vomiting (PDF, 123KB)

For additional guidance on nausea and vomiting, see also the BC Inter-professional Palliative Symptom Management Guidelines produced by the BC Centre for Palliative Care, available at: www.bc-cpc.ca/cpc/symptom-management-guidelines/

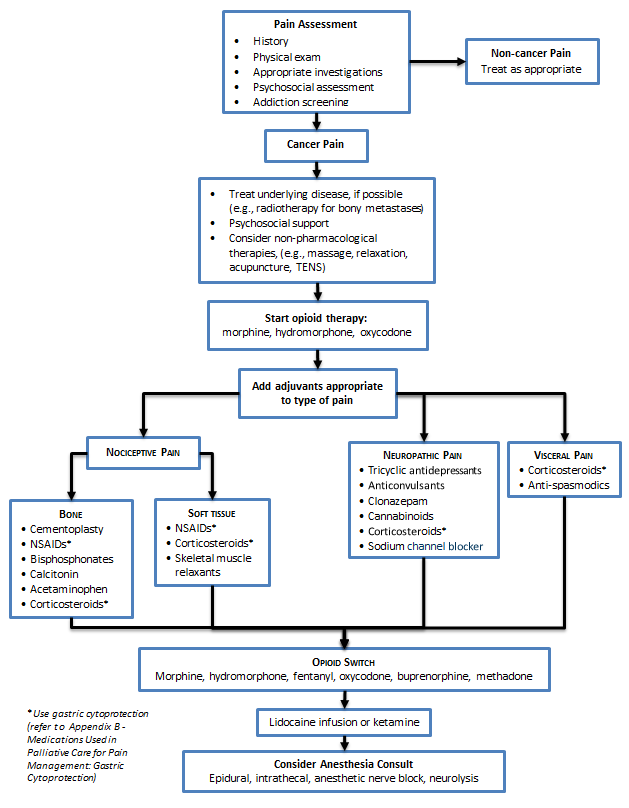

Key Recommendations | Assessment | Management | Pain Management Algorithm | Appendices

Key Recommendation

- Follow opioid management principles.

- Utilize adjuvant medication for pain-specific management.

Assessment

Signs and Symptoms

Use the OPQRSTUV mnemonic to assess pain:

Table 1: Pain Assessment using Acronym O,P,Q,R,S,T,U,V

| O | Onset | e.g., When did it start? Acute or gradual onset? Pattern since onset? |

| P | Provoking / palliating | What brings it on? What makes it better or worse, e.g., rest, meds? |

| Q | Quality | Identify neuropathic pain (burning, tingling, numb, itchy, etc.) |

| R | Region / radiation | Primary location(s) of pain, radiation pattern(s) |

| S | Severity | Use verbal descriptors and/or 1-10 scale |

| T | Treatment | Current and past treatment; side effects |

| U | Understanding | Meaning of the pain to the sufferer, “total pain” |

| V | Values | Goals and expectations of management for this symptom |

Physical Exam

Look for signs of tumour progression, trauma, or neuropathic etiology: hypo- or hyper-esthesia, allodynia (pain from stimuli not normally painful).

Management

- Continuous pain requires continuous analgesia; prescribe regular dose versus prn.

- Start with regular short-acting opioids and titrate to effective dose over a few days before switching to slow release opioids.

- Once pain control is achieved, long-acting (q12h oral or q3days transdermal) agents are preferred to regular short-acting oral preparations for better compliance and sleep.

- Always provide appropriate breakthrough doses of opioid medication, ~10% of total daily dose dosed q1h prn.

- Incident pain (e.g., provoked by activity) may require up to 20% of the total daily dose, given prior to the precipitating activity.

- Use appropriate adjuvant analgesics at any step (e.g., NSAIDs, corticosteroids).

- Record patient medications consistently.

1) Opioid Selection

| Issue | Preferred Opioid Medication | Avoid |

| Difficult constipation | fentanyl transdermal or methadonea | |

| Renal failure | fentanyl transdermal or methadonea | morphineb, codeine, meperidinec |

| Compliance and convenience | time release formulations (e.g., morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone) | |

| Neuropathic pain | oxycodone or methadoned (anecdotal evidence) | |

| Opioid naïve | low dose morphine, hydromorphone or oxycodone | fentanyl transdermal patch (risk of delayed absorption and overdose potential), sufentanil |

| Injection route (e.g., SC) |

morphine, hydromorphone, |

oxycodone (injectable) is not available in Canada |

| Patient is at extreme risk of respiratory depression | Buprenorphine transdermal patchf |

- Fentanyl is primarily (75%) cleared as inactive metabolites by the kidney and methadone is cleared hepatically.

- Morphine is the least preferred in renal failure because of renally cleared active metabolites.

- Meperidine (Demerol®) should not be used for the treatment of chronic pain.

- In 2018, Health Canada removed the requirement for an exemption to the federal restriction on methadone prescribing. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia has released appropriate guidance on prescribing methadone, a Methadone for Analgesia Guidelines, and a new Prescribing Methadone practice standard. Physicians are expected to acquire the relevant education and training to prescribe methadone for analgesia. This can be demonstrated through completion of the Canadian Virtual Hospice Methadone for Pain course (methadone4pain.ca) and/or by reading the Methadone for Analgesia Guidelines.

- When changing from oral route to buccal or rectal route, use 1:1 dosing with the oral 10mg/ml concentrated solution, and modify if needed depending on effect. If larger doses are required, a more concentrated solution may be compounded, up to a maximum of 40mg/ml. (Reference: Hawley, Wing, and Nayar, Methadone for Pain: What to Do When the Oral Route Is Not Available. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015 Jun 49(6):e4-6.) Island Health hospital pharmacy will concentrate to 50mg/ml.

- Not covered by BC Pharmacare.

2) Opioid Switching (“rotation”)

- Switch to another opioid when inadequate analgesia is obtained despite dose-limiting adverse effects (AEs). This allows for clearance of opioid metabolites and possibly more effective opioid receptor agonist profile from the new drug.

- Switch to an equianalgesic dose of the second opioid, bearing in mind that published ratios are only a guide and that reassessment and dose modification are required.

- When switching because of AEs (e.g., delirium or generalized hyperalgesia), determine the equianalgesic dose and reduce this dose by 25%. Observe closely, allowing for onset of the new and wearing-off of the previous drug.

- Refer to Appendix B - Equianalgesic Conversion for Morphine.

3) Addressing Adverse Effects from Opioids

If the adverse effect (AE) is not managed symptomatically and persists for more than one week, switch to another opioid.

|

Adverse Effect |

Intervention |

|

Constipation |

|

|

Nausea |

|

|

Sedation |

|

|

Myoclonus |

|

|

Delirium |

|

|

Pruritus, sweating |

|

*Cancer, GI malignancy, GI ulcer, Ogilvie’s syndrome and concomitant use of certain medications (e.g. NSAIDs, steroids, and bevacizumab) may increase the risk of GI perforation in patients receiving methylnaltrexone. [Health Canada MedEffect Notice: http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2010/14087a-eng.php]

4) Adjuvant Analgesics

- Select based on type of pain and AE profile. Optimize dosing of one drug before trying another. Discontinue adjuvant drug if ineffective.

5) Severe opioid-resistant cancer pain

- Consult a palliative care specialist for advice.

Pain Management Algorithm (Click image to access full-scale PDF version)

List of Abbreviations

| AEs | adverse effect |

| GI | gastrointestinal |

| NSAIDs | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| SC | subcutaneous |

| TENS | transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation |

| UTI | urinary tract infection |

Appendices

- Pain Management Algorithm (PDF, 34KB)

- Appendix A - Equianalgesic Conversion for Morphine (PDF, 120KB)

- Appendix B - Medications Used in Palliative Care for Pain Management (PDF, 153KB)

For additional guidance on pain management, see also the BC Inter-professional Palliative Symptom Management Guidelines produced by the BC Centre for Palliative Care, available at: www.bc-cpc.ca/cpc/symptom-management-guidelines/

References

- Kobierski, L et al. Hospice Palliative Care Program. Symptom Guidelines. Fraser Health Authority. 2009 April. Available at:www.fraserhealth.ca/professionals/resources/hospice_palliative_care/hospice_palliative_care_symptom_guidelines

- Schwartzstein RM, King TE, Hollingsworth H. Approach to the patient with dyspnea. UpToDate. 2009 Jan 1; 17.1.

- Membe SK, Farrah K. Pharmacological management of dyspnea in palliative cancer patients: Clinical review and guidelines. Health Technology Inquiry Service. Canadian Agency for Drugs & Technologies in Health. 2008 July.

- Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jan;148(2):141-6.

- Rodin G, Katz M, Lloyd N, et al. The management of depression in cancer patients: A clinical practice guideline. Cancer Care Ontario. 2006 Oct. Available at: www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=13930

- Brietbart W, Dickerman AL. Assessment and management of depression in palliative care. UpToDate. 2008 Jan 31; 16.1.

- Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):147-159

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the Effective Date.

This guideline was developed by the Family Practice Oncology Network and the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, approved by the British Columbia Medical Association, and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

The Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee

|

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

Contact Information: Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, Email: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Disclaimer The Clinical Practice Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem, and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problem. We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional. |