Overview of BC geology

Accessible geoscience information for a broad audience in government, industry, and the general public. Highlighted are a few commodities in British Columbia. Contact us for further information about these and other areas of geology in British Columbia.

Geology | Commodities | GeoTours

The Geology of British Columbia

A brief introduction

The geological history of western North America has been, and continues to be, shaped by its position on the eastern rim of the Pacific Ocean. The modern Pacific Ocean’s basin is the successor of the original ocean which split Laurentia - our continent’s cratonic core - away from the rest of the Precambrian supercontinent Rodinia, an ocean that widened until in late Paleozoic time, it became Panthalassa, the World Ocean. Unlike the eastern side of the continent, where continental collision was followed by re-opening of the Atlantic Ocean - the “Wilson cycle” - western North America has always faced the same active ocean basin. Its tectonic evolution has always been that of an active margin, affected first by multi-episodic rifting, and then by plate-margin subduction and transcurrent faulting, over a 700 million year period of time. Throughout this long interval, fluctuating regimes determined by relative plate vectors have created the complex and varied geology and topography of the region; its thrust belts, volcanoes, and granite canyons; its scarps, plateaus, and cordilleras.

The geological history of this area can be viewed as four distinct plate-tectonic phases. The Rifting/Open Margin phase lasted from initial breakup at about 700 Ma (late Proterozoic) until 400 Ma (Middle Devonian), when widespread subduction began along the margin. The Oceans and Islands phase commenced as subduction built arcs and the continent retreated away from them, creating a scenario like the modern southeastern Pacific ocean. This phase lasted until about 180 Ma (Early Jurassic), when opening of the Atlantic ocean reversed the motion of North America such that it drove strongly westward relative to the long-standing subduction zones off its west coast, creating a broad zone of compression in the offshore arcs and ocean basins as well as its own miogeocline (Collisional/Orogenic phase). The final, Post-Collisional phase commenced during the Early Tertiary when parts of the East Pacific Rise subducted under the continent and turned the plate margin from pure subduction to a regime with both transcurrent faulting and continued subduction of short, remnant segments. Industrial mineral deposits formed during each of these tectonic phases. Combined effects of two or more phases were required to form some of these deposits.

The Cordilleran miogeocline developed during the Rifting/Open Margin phase, from its inception with deposition of the late Proterozoic, syn-rifting Windermere Supergroup, through the deposition of the thick sequences of Paleozoic-early Mesozoic carbonate and terrigenous siliciclastic strata that are now beautifully exposed in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. The Mt. Brussilof magnesite deposit is hosted by Middle Cambrian carbonate within this continental shelf sequence. Equivalent platformal strata are best exposed in the southwestern United States, the Grand Canyon being a world-renowned example. The opening of Panthalassa was not a single event in western North America: convincing Cambrian as well as late Proterozoic rift-related sequences occur, and alkalic to ocean-floor basalts in the miogeocline range through Ordovician into Devonian age. The implied protracted nature of this rift event, in contrast to the short-lived and efficient opening of the Atlantic Ocean, continues to puzzle. The exact identity of the missing twin continent or continents, also provides grounds for lively debate, with Australia, Australia/Antarctica, and Siberia attracting the most adherents.

The Oceans and Islands phase began in Devonian-Mississippian time with the first widespread arc volcanism and plutonism along the continent margin: these rocks are recognized from southern California to Alaska. West of the North American miogeocline, a large portion of California, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and most of Alaska are made up of rocks of intra-oceanic island arc to oceanic affinity that occur in relatively coherent packages separated from each other by faults. These assemblages, famously termed a collage of “suspect terranes” by Peter Coney and Jim Monger, had uncertain relationships to the North American continent during at least part of their history. Most of them have now been shown either to contain faunas of eastern Pacific affinity (an excellent example can be viewed at the Lafarge limestone quarry near Kamloops, B.C.), or to exhibit sedimentological, geochemical and/or historical aspects that link them, however distally, to the continent. Some, however, are more convincingly exotic imports: the Cache Creek Terrane of central British Columbia with its Tethyan, Japanese-Chinese, late Permian fusulinid fauna; Wrangellia and Alexander, a linear belt on the coasts of B.C. and southeastern Alaska, with its late Paleozoic cold-water, Baltic-affinity fauna; and fragments of continental crust in Alaska with Precambrian ages that are unknown in North America.

At present, the Pacific Ocean is highly asymmetric, its west side festooned with island arcs, its east side bare, bordering a continental margin made up of fragments of just such arcs and marginal oceans. It is reasonable to suppose that both sides of the Pacific were once mirror images. However, opening of the northern Atlantic Ocean at about 180 Ma destroyed that symmetry. Although earlier compressional events affected the suspect terranes, their thrusting on top of the North American miogeocline dates from the latest Early Jurassic, roughly 183 Ma - the same age as early rift basalts on the eastern seaboard. From that time until the end of the Mesozoic, both suspect terranes and sedimentary strata of the miogeocline were stacked into a complex but overall easterly-tapering thrust wedge. Oceanic terranes incorporated into the wedge have provided both asbestos (Cassiar Mine) and jade deposits. During this Collisional/Orogenic phase, successive Jurassic and Cretaceous magmatic arcs draped across the growing accretionary collage. Numerous dimension stone quarries exploit granites from this phase. The notably voluminous mid-Cretaceous arc was probably linked to an episode of rapid subduction around the entire northern Pacific Rim. Broad plutonic provinces of this age occur from China, through Russia, into Alaska and British Columbia and south into California and Mexico - a spectacular example of the global geological consequences of relative plate motion.

Towards the end the Collisional/Orogenic phase, dextral (Pacific-northward) transcurrent motion became an increasingly important part of tectonic development, with at least hundreds of kilometres of displacement along faults such as the Denali, Tintina, Pinchi and Fraser. By early Tertiary time, thrusting in the Canadian Rockies and Foreland Belt had ceased, and crustal extension was accompanied by volcanism and graben development in southern British Columbia and northern Washington-Idaho. At about 38 Ma ago, the edge of North America began to impinge on the East Pacific Rise, shutting off subduction along increasingly long sections of the margin. Major dextral faults - the San Andreas, Queen Charlotte, and Denali faults - began to express the strong component of lateral motion between the American and Pacific plates. Some 300 kilometres of crustal extension related to this lateral motion generated the Basin and Range Province in the western United States. Limited subduction continues today off the coast of Washington, giving rise to the Cascade volcanoes; and the westward turn of the continent margin in Alaska creates a continuing collision zone in the Wrangell and Alaska Ranges, resulting in North America’s highest summits. Late Cenozoic uplift, perhaps due to mantle heating events, has rejuvenated the Canadian Rockies and the Coast Mountains. In terms of industrial mineral deposits, late Cretaceous and Cenozoic volcanic and terrestrial deposits of bentonite, diatomaceous earth, pumice, zeolites, and opals have attracted exploration and mining interest.

The saga continues, with the recent February 28, 2001 earthquake in Washington State rattling our knick-knack shelves and causing short term cell-phone and 911 overloads. This west coast is by nature Pacific Rim, not just in cultural orientation, but in terms of day-to-day tectonic reality as well.

For more information:

Geological Survey of Canada, Canadian Cordillera Geoscience

Nelson, J. and Colpron, M. (2007): Tectonics and Metallogeny of the British Columbia, Yukon and Alaskan Cordillera, 1.8 Ga to the present. In: Goodfellow, W D (Ed.), Mineral deposits of Canada: a synthesis of major deposit-types, district metallogeny, the evolution of geological provinces, and exploration methods. Geological Association of Canada, Mineral Deposits Division, Special Publication no. 5, 2007 p. 755-791.

Nelson, J., Colpron, M., and Israel, S., 2013. The Cordillera of British Columbia, Yukon and Alaska: tectonics and metallogeny. In: Colpron, M., Bissig, T., Rusk, B., and Thompson, J.F.H., (Eds.), Tectonics, Metallogeny, and Discovery - the North American Cordillera and similar accretionary settings. Society of Economic Geologists, Special Publication 17, pp. 53-109.

Pioneering geology in the Canadian Cordillera

Although not intended to be comprehensive, the papers presented in 'Pioneering Geology in the Canadian Cordillera' give a broad cross-section of geology in the Canadian Cordillera. The volume begins with a presentation of the vivid history of gold rushes and mining. This colourful discussion of events that put British Columbia `on the map’ is presented by Bob Griffin, a researcher with the Royal British Columbia Museum. The evolution of geologic thought by scientists from the Geological Survey of Canada, universities and industry is then discussed by Chris Yorath. Complimentary activities of provincial geologists are described by Atholl Sutherland Brown in his summary of the history of the British Columbia Geological Survey. These papers are followed by accounts of the evolution of research in major geologic fields in the Cordillera including engineering geology, mining, petroleum geology, geophysics, paleontology and marine geology. Each of these areas is discussed separately by well known specialists. Gary Rogers, a prominent seismologist with the Geological Survey of Canada, discusses the history of earthquake studies in British Columbia. Early mining in British Columbia, as exemplified by the development of a world-class mine at Britannia, is discussed by Marilyn Mullan. Doug VanDine, Hugh Nasmith and Charlie Ripley provide a summary of historical events in engineering geology and Jim Murray and Bill Mathews describe developments in marine geology, the province’s newest geological science. Rolf Ludvigsen, an eminent paleontologist well known for his work on the Burgess Shale fauna which is now preserved in a World Heritage Site, describes developments in paleontology, emphasizing the search for Cambrian and Precambrian fossils. The history of the petroleum industry in the Cordillera is summarized by Nick Wemyss, formerly with the British Columbia Petroleum Geology Branch. The volume concludes with a first-hand account of geologic mapping by the Geological Survey of Canada in the `early days’ and a comparison with today by John Wheeler, an eminent Cordilleran geologist.

The papers are written by prominent researchers, many of whom have had direct personal experience in the development of their fields. For example, Atholl Sutherland Brown describes the history of the British Columbia Geological Survey from the unique perspective of a former head of the Geological Division (1974-1984). Similarly, Marilyn Mullan describes the events leading to the establishment of the Britannia mine as a National Historic Site, a process with which she herself was intimately involved. In addition, Chris Yorath and John Wheeler describe activities of the Geological Survey of Canada, an organization with which both writers have long been associated. Chris Yorath also writes from the perspective of author of the recently released book, Where Terrains Collide (Yorath, 1991) and coeditor of the Decade of North American Geology volume entitled Geology of the Cordilleran Orogen in Canada (Gabrielse and Yorath, 1992). Both these volumes are recommended for further reading, the first for the non-specialist and the second for an excellent technical overview of Cordilleran geology.

View Pioneering Geology in the Canadian Cordillera (Open File 1992-19; PDF, 1.19 MB)

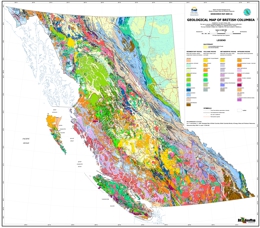

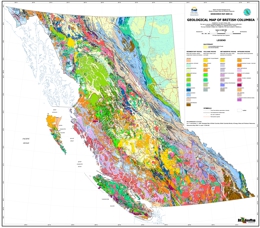

Geological Maps

BC Geological Map at 1:2 million, best suited for printing as a single sheet: View Geoscience Map 2009-01 (PDF, 275.3 MB)

Geoscience Maps from regional compilation, in PDF for download (some containing digital data)

BC Digital Geology

Province-wide digital coverage of bedrock geology, including details from regional compilation at scales from 1:50,000 to 1:250,000

Information about selected commodities in British Columbia

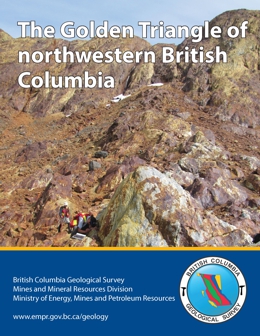

The Golden Triangle of northwestern British Columbia

The Golden Triangle includes most of the major gold, silver and copper deposits in west-central Stikinia, a long-lived oceanic arc terrane that extends for about 1000 km along the length of the Canadian Cordillera. Most deposits are related to the Hazelton Group and affiliated intrusions (Latest Triassic to Middle Jurassic). More than 150 mines have operated in the region since prospectors first arrived near the end of the 19th century. Important past-producing mines include Granduc, Eskay Creek, Anyox, Kitsault, Premier/Dilworth, and Snip. Current mines include Brucejack (Pretium Resources Inc.), an epithermal gold-silver deposit that began commercial production in 2017, and Red Chris (Imperial Metals Corporation), a porphyry copper-gold deposit that began commercial production in 2015. The Golden Triangle contains numerous proposed mines and is being intensively explored. Enhanced infrastructure is encouraging exploration and development.

Rare metals in British Columbia

Historically, exploration for rare metals has been sporadic. Although a number of occurrences and prospects have been identified, few have advanced to developed resources or reserves. Carbonatite and syenite complexes host British Columbia’s most advanced rare earth, niobium, and tantalum prospects. Specialty metals concentrations are also known in mineral occurrence types such as pegmatite/granite, placer/paleoplacer, sedimentary phosphate, and skarn.

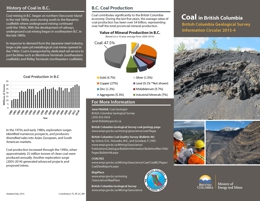

Coal in British Columbia

Coal contributes significantly to the British Columbia economy. During the last five years, the average value of coal production has been over $4 billion, representing over half the total provincial mineral production. Coal is typically classified on the basis of contained carbon and volatiles (hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulphur, and phosphorus). High-rank coals are high in carbon (and therefore heat value), and low in volatiles; low-rank coals are low in carbon but high in volatiles. Information Circular 2015-04 is a pamphlet describing the distribution, origin, production, and uses of coal in the province.

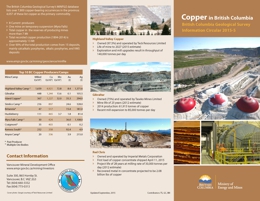

Copper in British Columbia

The British Columbia Geological Survey’s MINFILE database lists over 7,800 copper-bearing occurrences in the province; 4,057 of these list copper as the primary commodity. Total recorded copper production (1894-2014) is approximately 13 Mt. Over 90% of the total production comes from 15 deposits, mainly calcalkalic porphyries, alkalic porphyries, and VMS deposits. Information Circular 2015-05 is a pamphlet describing the distribution, origin, production, and uses of copper mined in the province.

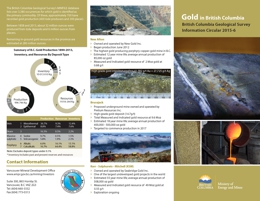

Gold in British Columbia

The British Columbia Geological Survey’s MINFILE database lists over 3,380 occurrences for which gold is identified as the primary commodity. Of these, approximately 700 have recorded gold production (400 lode producers and 300 placer). Between 1858 and 2013, about 32 million ounces were produced from lode deposits and 6 million ounces from placers. Remaining in-ground gold resources in the province are estimated at 280 million ounces. Information Circular 2015-06 is a pamphlet describing the distribution, origin, production, and uses of gold mined in the province.

Molybdenum in British Columbia

The British Columbia Geological Survey’s MINFILE database lists 1,381 molybdenum-bearing occurrences, 460 of which list molybdenum as the primary commodity. Mo and Cu-Mo porphyries are the main deposit types. The developed Mo porphyries in B.C. are classified as low-fluorine type, distinct from the high-fluorine climax type known in the western US. Most are low-grade bulk tonnage targets, but some deposits with high-grade cores are potentially amenable to underground mining, such as the MAX (280 Kt @ 1.17% Mo) and Davidson (6.7 Mt @ 0.36% Mo). Porphyry Cu-Mo deposits, in particular Highland Valley Copper, account for a large proportion of B.C. molybdenum production, resources, and reserves as a by-product of copper production. Information Circular 2015-07 is a pamphlet describing the distribution, origin, production, and uses of molybdenum mined in the province.

Nickel in British Columbia

Nickel is mainly used as an alloy with other metals, such as chromium, to make heat resistant and stainless steels. These steels are then used to make everything from domestic appliances to jet airframes. Information Circular 2015-08 is a pamphlet describing the distribution, origin, production, and uses of nickel mined in the province.

Jade in British Columbia

Jade is a commercial term for green, white, black, or yellow-brown jadeite and nephrite. Jadeitite is a rock that consists of the mineral jadeite (a sodium-rich, high pressure pyroxene), whereas nephrite consists of amphibole minerals (tremolite-actinolite) in which prismatic to needle-like crystals are arranged in randomly oriented bundles. All of the known jade deposits in B.C. are nephrite. Both types of jade are commonly associated with serpentinites, although nephrite may also be found in dolomitic host rocks. Information Circular 2015-9 is a pamphlet describing the distribution, origin, production, and uses of jade mined in the province.

View Information Circular 2015-09 (PDF, 3.3 MB).

宣传册描述了BC玉的分布、来源、生产、和用途

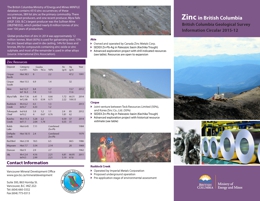

Zinc in British Columbia

The British Columbia Ministry of Energy and Mines MINFILE database contains 4510 zinc occurrences; of these occurrences, 589 list zinc as the primary commodity. There are 569 past producers, and one recent producer, Myra Falls (092F 330). B.C.’s largest producer was the Sullivan Mine (082FNE052), which yielded nearly 8 million tonnes of zinc over 100 years of production. Global production of zinc in 2014 was approximately 12 million tonnes. Most (60%) is used for galvanizing steel, 15% for zinc based alloys used in die casting, 14% for brass and bronze, 8% for compounds containing zinc oxide or zinc sulphate, and most of the remainder is used in other alloys (source: International Zinc Association).

GeoTours

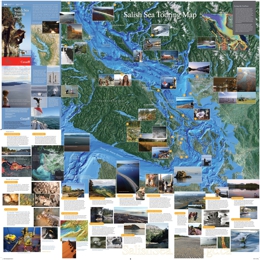

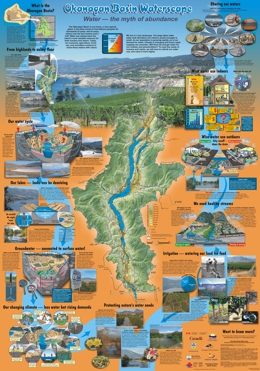

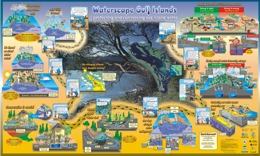

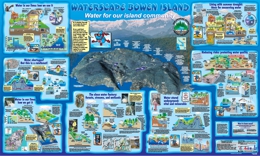

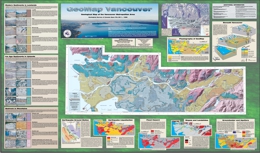

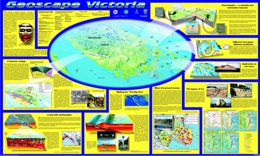

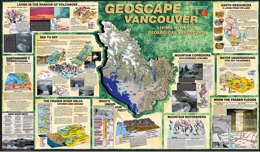

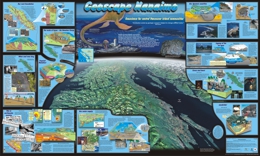

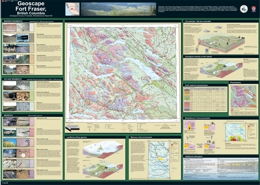

British Columbia field trip guidebooks, geoscience highway maps, Geoscapes, and GeoTours

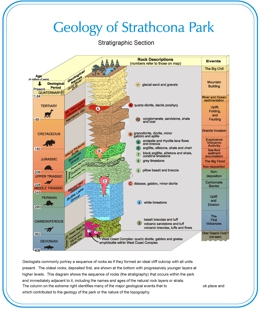

Geology of Strathcona

Geology of Strathcona